Photographers have a troubled relationship with the unity-making demands of theme.

One of the early questions a gallery curator or book editor will ask an artist is, “What holds all these together?” In other words, what exists between the images that will move a viewer along a story? Sometimes the answer is external, such as images of an event or situation. Sometimes the answer is found in the varied manifestations of a physical place. And sometimes the answer is technical, a type of camera or process.

“Random Access: Photographs by John T. Hill”

Published by Steidl, 2022

review by W. Scott Olsen

But I also remember a lecture when I was an undergraduate, although I don’t remember what class, what professor, or what year. He wrote the word “the” on the chalkboard. “Let’s go back to basics,” he said. “Look at the letter T. There is no actual relation between that letter and the H that follows. They are not touching. The do not cause or affect each other. Whatever relationship there is, is one we impose. In fact, look at the T again. All that’s real is chalk dust on the board. That the dust forms a shape we recognize as a letter, that the letter has a sound, that the letter when placed near other letters forms a word that has a meaning as well as a sound, are all things we impose or project onto what we’re seeing. Relationships are hard-wired into the way we perceive the universe, but they also limit what else we might see.”

At the time, this was an eye-opening and freeing revelation for me.

We seem to insist on grouping individual images into larger gatherings. Perhaps this is because we have a habit of speed, swiping left or right at disco pace, strolling through art spaces so fast we gain cardiac benefit. I have come to believe benches in galleries and museums are for rest much more than contemplation.

And yet, I also believe every photographer has the same wish. Here, we want to say to the world, is a bunch of images I really like. They have nothing to do with each other. They have everything to do with themselves, just themselves, one by one, individually, alone.

John T. Hill’s new collection, Random Access, is a brilliant collection of individual images. Each one is an eloquence of composition and tone. Turn the page from one to another and you might wonder what one has to do with the other, but that’s not the point at all. Look at this one, the book says, then the second. Not look at this one and the second.

The compositional power and resulting emotional/intellectual engagement should not be a surprise. Hill taught both graphic design and photography at the Yale University School of Art, and co-founded Yale’s Department of Photography where he was the first co-director of graduate studies. Graphic design is the underlying value system for all these images.

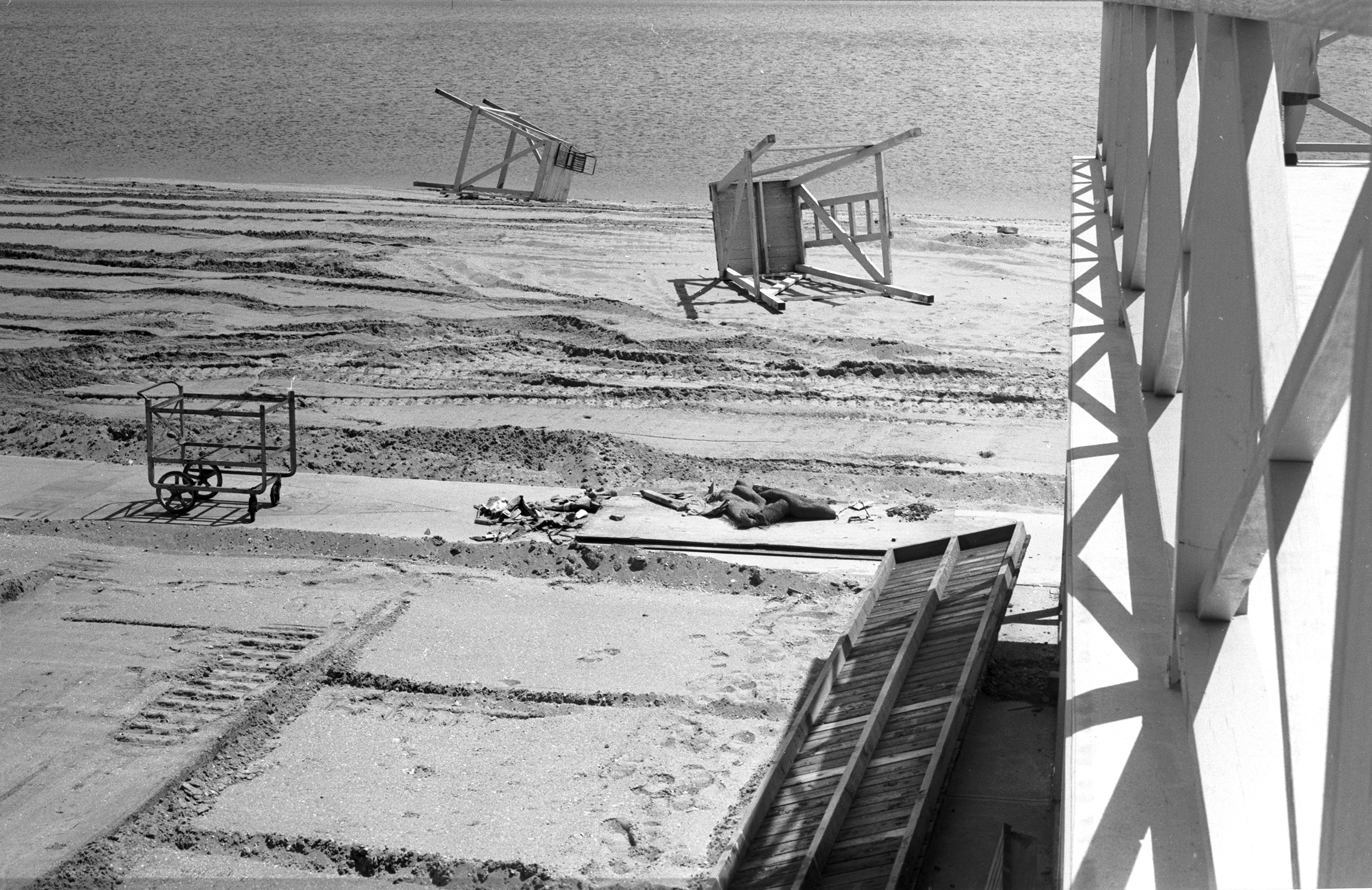

A seemingly random image, “Savin Rock Beach, Connecticut, After Storm, September, 1958” simply shows a vacant beach after a storm has passed. There are some overturned lifeguard chairs, the frame of some type of cart, the edge of some type of platform. The image is without people. There is no sense of social or personal loss. And yet this image could fill a seminar on composition. There are regular parallel and perpendicular lines in the sand, echoed by what appear to be tractor tread marks. The cart and overturned chairs rest (roughly) on the 1/4 lines. The shadows from the platform railing offer an engaging dissonant note to the others, as do the splayed legs of the chairs. There is the smoothness of the ocean, curves both physically and tonally to the mid-ground sand, then the hard lines of the foreground beach. Centered in the image are two areas, both jumbled and chaotic.

The eye travels this image with a persistent air of exploration about a world remade after a storm.

In his very brief Preface, Hill writes, “When I’m holding a camera, I am receptive to whatever I may find most provocative. Baudelaire described this in his account of the flaneur, that person who goes out with an open eye and mind. My goal is to record chance happenings that strike a personal visual chord. In these photographs, what drives me are two things. One is selecting a worthy subject The second is to create a visual tension.”

The book offers a short essay called “Pause Effect,” by writer and NEA Fellow Kathy Leonard Czepiel, who says, “As a ‘persistent observer’ Hill catalogs what he calls ‘found compositions,’ as if the world were doing the composing for him.” She then quotes teacher and journalist Stephen Kobasa saying, “His [Hill’s] work is always an invitation to join him in some exercise of attention.”

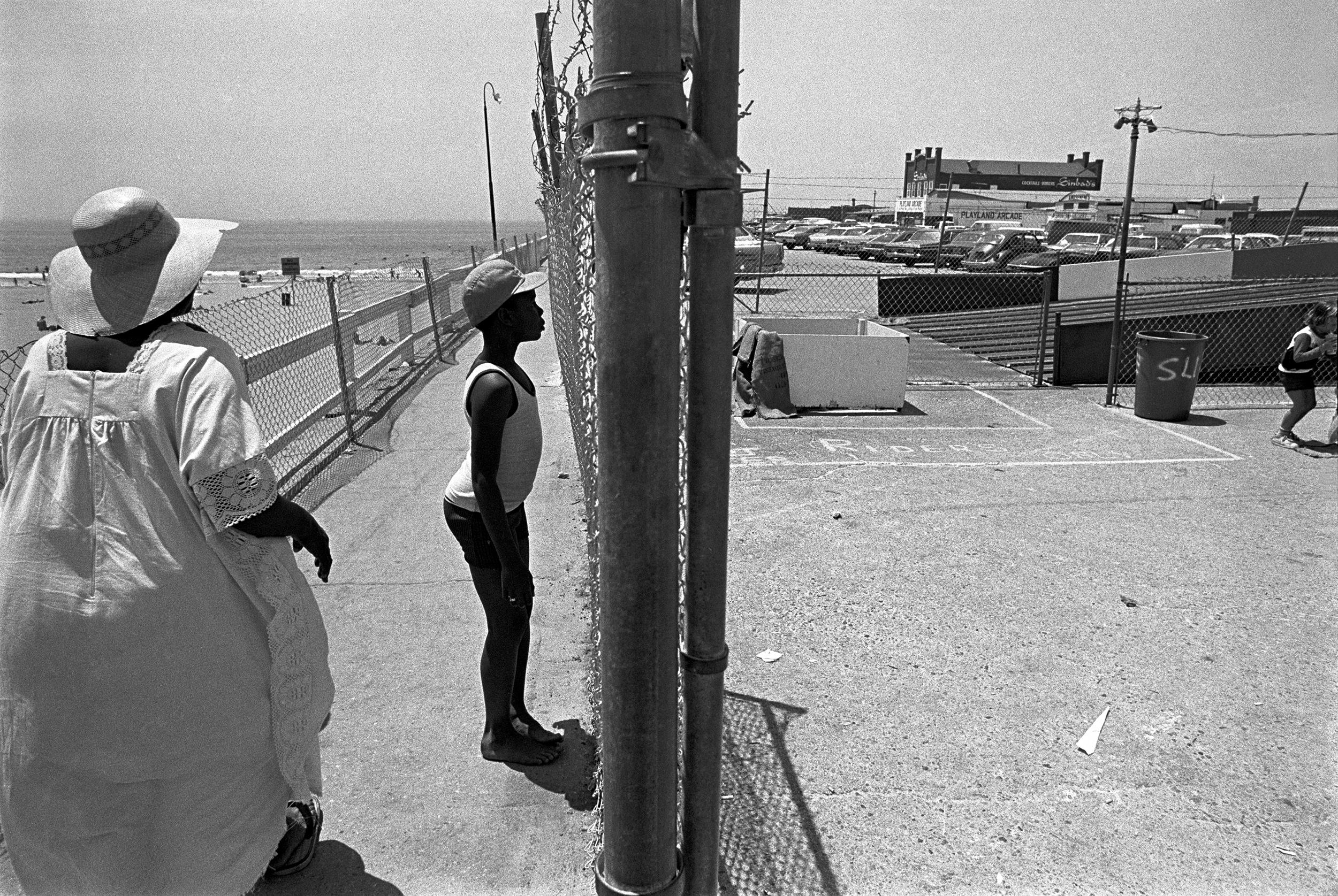

Looking at Hill’s images, I often wonder why I find them so appealing. The why is important. And it occurs to me there is a comparison (for me, at least) with Piet Mondrian. Hill’s images and Mondrian’s paintings look nothing like each other, of course. But line and tone and color are the real subjects. Hill’s “Santa Monica Boardwalk, California, ca. 1960” should not be a successful image. It’s just a guy looking at a fence – until you realize what’s going on with the lines and tones.

In an Introduction, Hill’s partner Corinne A. Forti writes, “Time fragments to intrigue and provoke. Simple images that stimulate the imagination to invite new meanings. These photographs, taken over 70 years, are indeed random. The collection is defined by visceral images, each inspiring personal readings. No explanation is offered.”

There are 79 images in the book, a full collection of both color and black and white, and every one needs and deserves to stand alone. Take the time to linger on one image at a time and the book is wonderful.

During his 19-year tenure as executor of the Walker Evans Estate, Hill produced a number of Evans books and exhibitions including Walker Evans: At Work, Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye, Walker Evans: Lyric Documentary and Walker Evans: Depth of Field. Other books he has designed, authored or co-authored include Calder by Matter, W. Eugene Smith Photographs, Edward Weston, Forms of Passion and May Day at Yale: Recollections 1970.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have a forthcoming or recently published photography book.