Love+War opens in Novoluhans’ke, Eastern Ukraine, five days before the Russian Invasion. The sky is gray, the temperature cold. There are the sounds of artillery and explosions, boots scuffling on sidewalks. Pulitzer Prize-winning conflict photojournalist Lynsey Addario and the person filming her, in flak jackets and helmets, are running for shelter. The video is hand-held, jumpy, immediate, and honest. They are running for their lives.

Incongruously, one local woman simply stands on the street, watching. Another woman walks by, and what we assume is her child riding a bicycle beside her. Just another day in Ukraine. Addario and her partner ask a third woman where they can find a bomb shelter or basement. “Why don’t you try to live like us, instead of hiding?” the woman asks. “This is how we live all the time.”

This is followed by Addario’s images from the invasion — burning buildings, a covered body on the street, the mass panic of people trying to escape, newborns in a warzone maternity ward where the parents are trying to decide upon a name.

In other words, the documentary begins with the dangerous, the horrible, anxiety, and fear, and in every part of it, there remains the strength of human dignity. This is the hallmark of Lynsey Addario’s photojournalism. In response to the atrocious, there is often the noble.

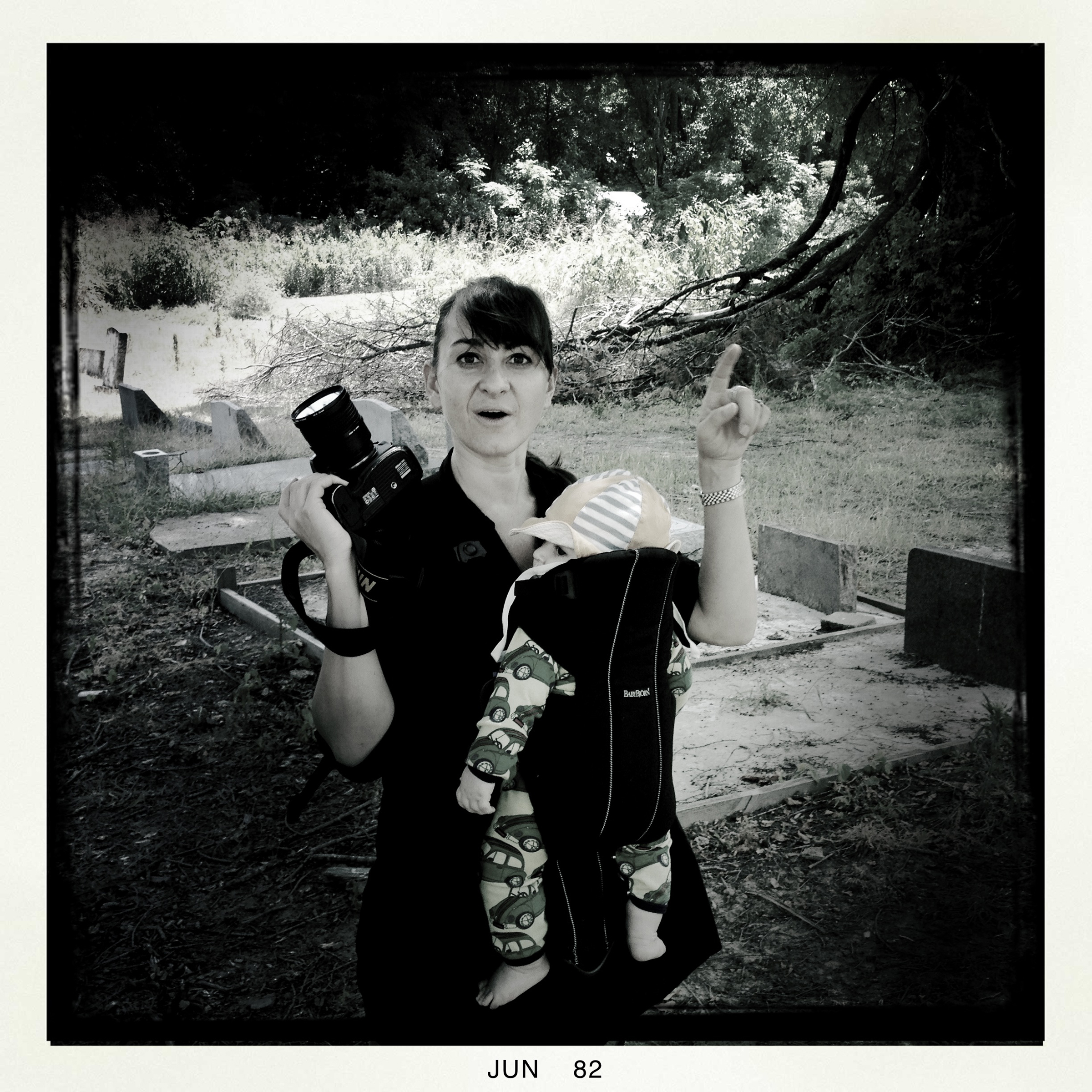

Love+War continues the stories and issues described in Addario’s 2015 best-selling memoir, It’s What I Do, but brings in her work since then — most notably her images from the war in Ukraine. The movie is not a plot-driven adventure story. It is, instead, a complicated, multi-layered, braided character study. How do you photograph a war scene and stay alive? What do you want your photographs to achieve? How do you keep your relationships — wife, mother, sibling, child, friend — from falling apart? How do your own conflicting desires churn your heart and soul? How do you stay sane? At every level, Addario’s life is a difficult balancing act.

It cannot be understated how good she is at what she does. Conflict photography is dangerous, frequently lethal, but in fact has very little to do with the adrenaline rush of battle. Instead, it has everything to do with finding a way, as a visual storyteller, to illuminate the human spirit. Addario’s work has won awards and found prestige because her vision is a love-filled response to the obscene.

Photographs that are simultaneously difficult and beautiful, and stopped the world for a moment — think of the image of Yulia Bondarenko, a Ukrainian teacher, holding an assault rifle in the back of a truck, ready to defend her country, which made the New York Times — resurface in the movie. (In fact, Bondarenko becomes a touching supporting character as Addario revisits her.) Likewise, the moment a mortar strike kills a civilian family, evidence of a war crime that made the New York Times front page, is caught on film. We get the moment, the image, and Addario’s gut-felt reaction.

Yet there is the other side of her life as well. It’s heartbreaking to hear one of her sons ask if mommy is downstairs and hear her husband say no, mommy’s in another country. It’s heartbreaking to hear Addario’s own wondering about her other son’s quietness. And it’s heartwarming to see them all together. As her husband, Paul, says during one interview, “It’s a compromise, right? She wants to do all of the things and be at home as well. And it’s just not possible.”

“In my heart,” Addario says, “all I want to be doing is shooting. It’s frustrating. I’m constantly tortured, like I’m not in the right place. But I come back. I’m supposed to be really happy…My head is always where I am not.”

There are photos and stories of Addario’s growing up, reminiscences with her sisters and parents, as well as intimate couch conversations with her husband about raising children and the future. The movie excels in the way layers of history and context combine to make a complex and nuanced portrait.

Love+War is an essential and necessary movie. It’s often difficult to watch because of the violence. And it’s often difficult because of the angst and regret. It’s suspenseful, anger-making, poignant, and loving all at once. It is an intimate portrait of a woman simultaneously pulled by a deep sense of purpose and the importance of her craft and her equally deep desire to be fully present in the lives of her family. The film cuts between action scenes, family scenes, and formal interviews with the same push-pull of her life. Occasional voice-overs provide context and it’s clear we’re exploring a difficult equation. Love + War = what?

For those who have read the memoir or know her work, the film offers particular joys, in that Addario’s mother, father, sisters, husband, and children all have voices. Sometimes we see them in-scene; sometimes they are interviewed more formally. Both ways they become real people with their own roles in the narrative, and they give a type of additional detail to the events and issues, which creates gravitas.

I read Addario’s memoir, It’s What I Do, when it first came out, and have been teaching it in college classes every year since then. I bring this up because throughout the film I kept remembering the conclusion to the book’s Prelude, where, while talking about the work of conflict journalists, she writes:

Under it all, however, are the things that sustain us and bring us together: the privilege of witnessing things that others do not; an idealistic belief that a photograph might affect people’s souls; the thrill of creating art and contributing to the world’s database of knowledge. When I return home and rationally consider the risks, the choices are difficult. But when I am doing my work, I am alive and I am me. It’s what I do. I am sure there are other versions of happiness, but this one is mine.

Love+War is often graphic, but that means it’s honest. And there are moments of hope. The appeal of this story goes well beyond its immediate subject. Every photographer of every sort should see this movie. More importantly, every person who has ever been moved or troubled by a photograph, every person who feels connected at any level to the events of the world, and every person who feels pulled in a thousand directions in their life, needs to see this unfolding. It’s a hard movie. And it’s eloquent.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC – OFFICIAL MOVIE PAGE

LYNSEY ADDARIO