The only clue we get to the specifics of Twelve Acres by Henry Head is one sentence, set alone, at the beginning of the book:

This work was inspired by the friendship that defined my teenage years and the Ozark creeks and hills that we called home.

And, remarkably, that one line is enough. That one line is a key that unlocks the resonance of a region and the oftentimes challenged metamorphosis of youth.

Henry O. Head – “Twelve Acres”

Published by Twin Palms Publishers, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

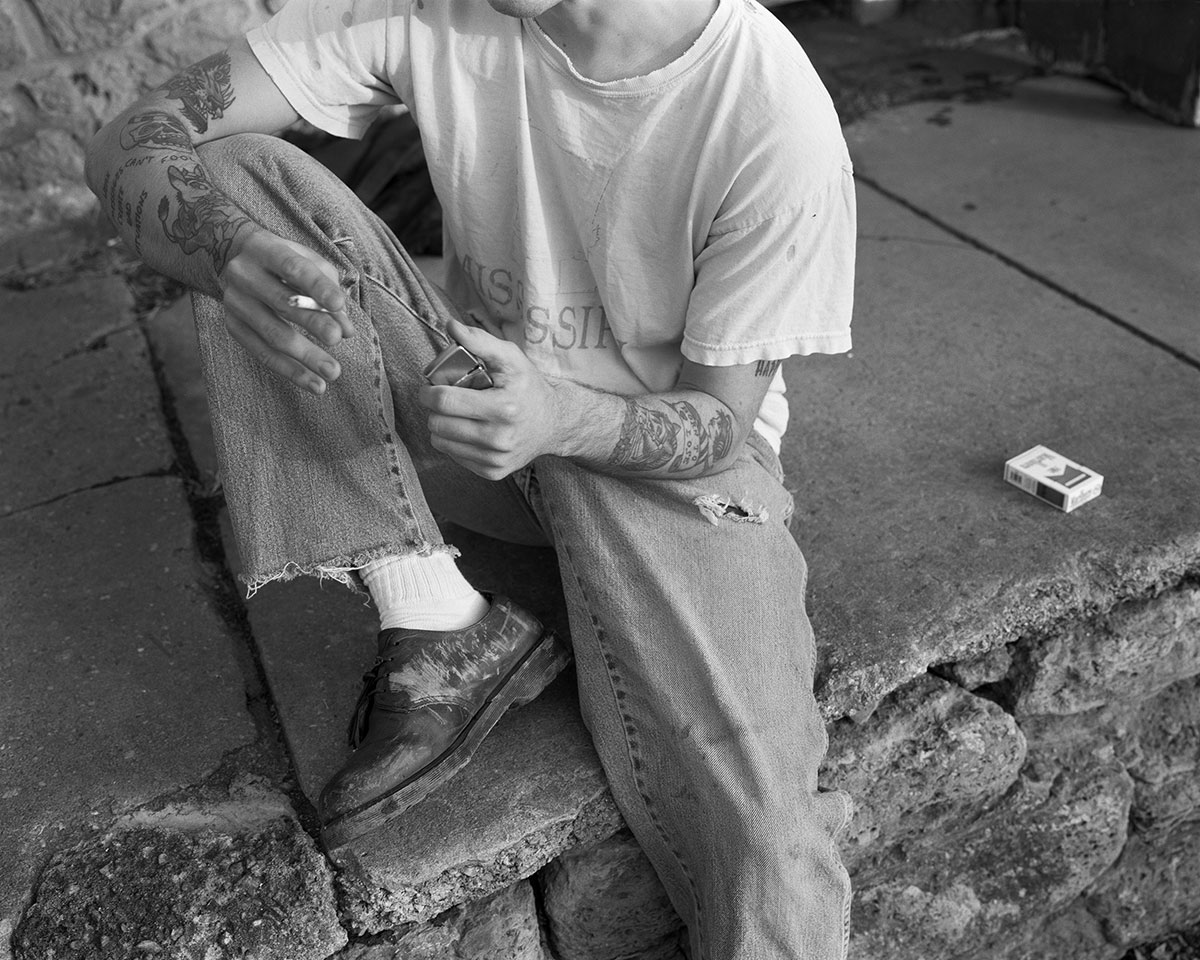

Twelve Acres is a remarkable book. It is not landscape photography in the sense that it seeks to document the mood of light in a certain area. It is not autobiographical, in that it does not (as far as I can tell) show the artist in various stages of growing up. And it’s not even really sociology or anthropology in that it does not try to give a wide vision to a defined community.

Instead, this book is about a milieu, a way of being, a poignancy that is frustrating, sad, frequently beautiful, oftentimes tragic, sometimes anger-making, and nearly inescapable. This is a book about what, for many people, the Ozarks of Missouri and Arkansas are like. The book does not say where the twelve acres are, exactly. And that doesn’t matter at all.

The images, all black and white, one after the other, find a way to articulate that indescribable sense of being in a place and mindset which is peculiar to the Ozarks. To be a teenager in the Ozarks is aimless. Some would say hopeless. Some would say entrapping. Others would say a beautiful and deep soul. They would all be right.

The images are candid: young boys climbing on the steel girders of a bridge, or resting in jeans and t-shirts with packs of cigarettes on a roof. There are images of hanging out by a river, wrestling, the occasional snake, one person way up in a tree, and a litter of spent shotgun shells. There’s an image of someone hanging out a car window while the car is at speed, another of two friends talking on railroad tracks. There are the occasional, barren, snow-covered fields.

The Ozarks are part of my own history, and I can tell you every image in this book is true with a capital T. It is a strange and wonderful and dangerous place.

At the end of this book, an essay by Alyssah Morrison seems, at first blush, to have absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the book. The essay does not talk about Henry Head, or the images in the book, or even photography in general. But the essay is stylistically unique, a memory of Morrison’s own childhood in the Ozarks. For example, one line reads:

Mac’s dad set up a zip line and she was in between two sisters and her grandma came over to give piano lessons and for a while there were pet rabbits in the house and Mac’s older sister wore bras and mascara and there was a metal bin for all of the girls bathing suits by the back door and I ate all of the marshmallows out of the Lucky Charms one night and Mac’s dad was furious but then couldn’t stop laughing and if you were really lucky you might get invited to go tubing at the lake where Mac’s mom Marna would drink margaritas and wear a bikini.

That’s just one sentence. And that kind of everything all at once-ness, the frenetic pace of a long sentence without commas, the breathless falling-forward, is what powers the images, even though the compositions and the subjects themselves are simple, quiet, and oftentimes minimal.

Twelve Acres is an eloquent photographic articulation of what it is like to be not young, but not old enough in the Ozarks. Yes, it is entirely possible I am projecting my own assumptions about the Ozarks into these images, but that remains one of the real powers of photography, to see ourselves somehow reflected in the images of others. I am also confident that nearly everyone will see themselves here, no matter where they are from.

There is another quote in the book at the end, just before the essay. It reads:

You remember that old town we went to, and we sat in the ruined window, and we tried to imagine that we belong to those times—It is dead and it is not dead, and you cannot imagine either its life or its death; the Earth speaks and the salamander speaks, the Spring comes and only obscures it.

That’s what this book is about. The photographs themselves are brilliant—their composition, their balance, the way they evoke an emotion that has its own sense of urgency. And while many of the images are common to rural photography, a worn-out barn, for example, not one of them feels as if it’s relying on old tropes. There is a real mastery of the power of black and white photography here, and the book design—large, high-quality paper, soft white pages with wide borders for the images, which are most often alone on the right, although several jump the gutter or reside only on the left side—is elegant.

If I told you Twelve Acres is a book of dreams, you would be hard-pressed to find that on any page. However, if I told you Twelve Acres is a book where dreams reside behind every image, you’d nod and understand.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.