For a great many photographers, Cuba is alluring.

Images of Cuba, and of Havana in particular, have filled all sorts of photobooks. Several of them are on my shelves. They are all particular and wonderful and vibrant. Each of them seeks to uncover a personal statement about what remains, for the entire planet, I believe, a romantic and mysterious island. I have spent hours turning those pages, imagining myself on those streets and among those buildings, listening to music which is somehow both raw and beautiful.

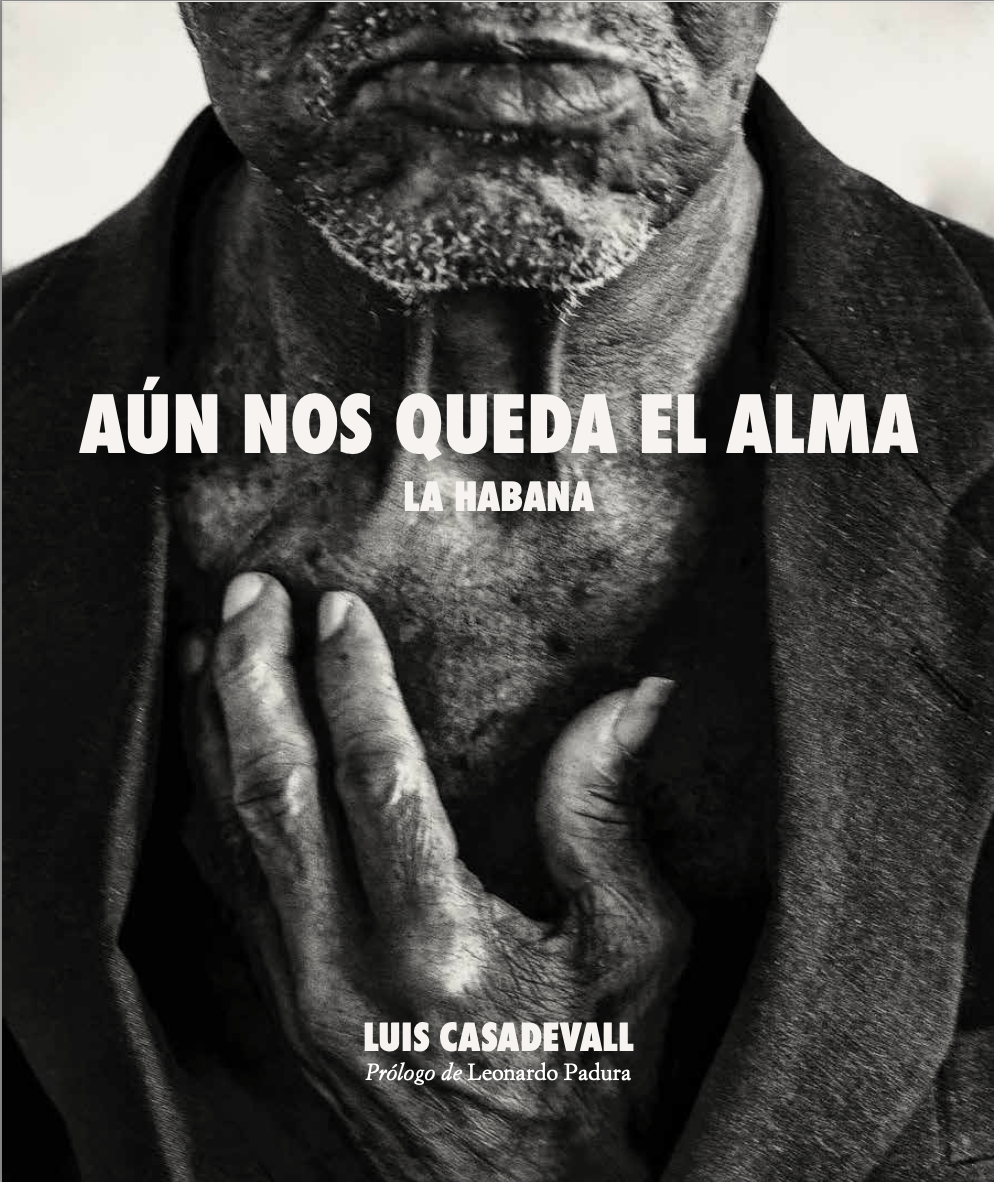

Luis Casadevall – Aún nos queda el alma (We Still Have The Soul)

Published by La Fabrica, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

But at another level, photobooks about Cuba, and of Havana in particular, have tended to cover the same ground: bright colors, old cars, crumbling buildings, ballerinas, cigars, the ocean.

What calls one photographer often calls many photographers. The challenge is to say something honest and new.

This is not a complaint as much as a way to set up how wonderful it is to come across a book about Cuba, and in this particular case, Havana, that speaks with what I consider to be a fresh voice.

Aún nos queda el alma (We Still Have The Soul), by Luis Casadevall, is a wonderful, emotional, and insightful collection. This is a way of telling a Havana story I have not seen before.

Casadevall began his career in advertising in Spain, and his career there was tremendously successful. But, according to the book’s inside cover text, a brief visit to Havana captured something essential in him.

He returned repeatedly over the course of 12 years, not as a tourist, but as someone who needed to understand the city’s pulse, its resilience and its beauty. Through over 65,000 photographs, he sought to capture the invisible, the essence of a wounded, yet dignified people.

Aún nos queda el alma (We Still Have The Soul) is a collection of black and white street photography, candid and yet not accidental, composed to tell stories. Yes, there are crumbling buildings, the occasional ballerina, the occasional old car, men and women with cigars, but the book focuses on the people, not as metaphors or types, but as individuals.

Many of the images are what we would call street portraits, or environmental portraits. Not posed, but the person-in-context as the subject. And I find myself lingering with interest, examining the faces, wondering about the stories, the histories, the loves and heartbreaks. Because the images are black and white, there is a step toward metaphor with each image.

In terms of book-arts and design, the images appear in changing places on the pages, which gives the book a dynamic feel.

While a career in advertising may lead toward hyper-precision and over-determined technique, that does not seem to be the case with Casadevall. There is a way to approach street photography which allows for the out of focus, for the blurred, for the slightly dissonant composition that manages to speak more directly to some kind of truth.

You could argue that this book is not only about what Havana looks like, but it is also a book that wants to be about what Havana is like for those who live there.

There is text in this book, all of it in Spanish, but the book (or at least my copy) also comes with a small, well-designed booklet which has the text in English. The result of this, for me, was twofold. First, as someone who does not understand more than just a little Spanish, I had to engage the images with no other context than location. No explanation of either purpose or focus. And the result was a slowing down, a more careful reading of every page, which was deeply pleasing and, I hope, insightful. Second, turning to the booklet, I was able to read several very brief essays of only a page or two by other writers and artists who know Casadevall’s work and the spirit of Havana as well.

For example, in the Preface, Leonardo Padura, who, among many other things, has won Cuba’s national literature prize, writes—

Faces, many faces. Black, white, mixed race; young adult, old; women, men. Groups, couples, solitary figures. Around them, a backdrop almost always marked by decay: ruins, peeling walls, dim and sometimes sordid settings, the inescapable imprint of poverty. Streets that seem to lead nowhere and finally, the sea. The sea as a space of freedom, purification, relief, or as a gateway to some celestial or earthly beyond. A city both possible and identifiable, where the parts interlocked to form a whole. All rendered with clear esthetic intention: spaces and figures seen through the raw prism of black and white, from perspective so close, it feels almost invasive—revealing ultimately dramatic.

In a later essay, author Tito Munoz writes—

A photograph is magic, no matter how you look at it.

Many people claim to know Havana, but Luis’s book, through his photographs, proves the exact opposite. Very few people truly know Havana in depth, all the way to its soul.

This book is far removed from any touristic memory. It pointedly rejects tired cliches.

Oddly, and intriguingly, there are two translations of the title. On the English booklet, the title is “We Still Have The Soul.” However, on the publisher’s website, the translation is “We Still Have Our Soul.” The difference between “the” and “our” is substantial, yet I would argue that both readings are true here. And I keep coming back to the book’s inside cover text—“… he sought to capture the invisible, the essence of a wounded, yet dignified people.”

The soul. Our soul.

One of the most interesting things about this book is Casadevall’s understanding of the way a single photograph can be narrative, and how a collection of photographs can expand that narrative, not into a single plot line, but into a character study of a culture. It could be an old woman talking on a public pay phone, children in school uniforms playing on the street, any number of images where the subject is framed by their environment—car windows, shutters, a manhole. “We Still Have the Soul,” Padura writes, “is a committed narrative, I would even say an intimate one.”

Yes, there are other visions of Cuba, and Havana, but this one loves a kind of realism—not in terms of photographic contrast or clarity, but realism of condition.

From my point of view, this book opens a window that I find fascinating and for which I am grateful.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.

Glen Fisher

February 16, 2026 at 16:41

A moving and insightful review of what looks like a wonderful book. Thanks Scott for sharing. PS I have been fortunate to travel to Havana myself – just the once – and struggled with precisely the issues you raise here – how to look past the touristic cliches, how to really see and feel the city and the people as they are, with humanity and dignity, how to relate a story that is not merely the tired echo of all the stories we have already seen and heard. This collection of images seems to do so magnificently.