“Art can no longer be merely a mirror, it must act as the organizer of the people’s consciousness… No form of representation is so readily comprehensible to the masses as photography.”

—El Lissitzky

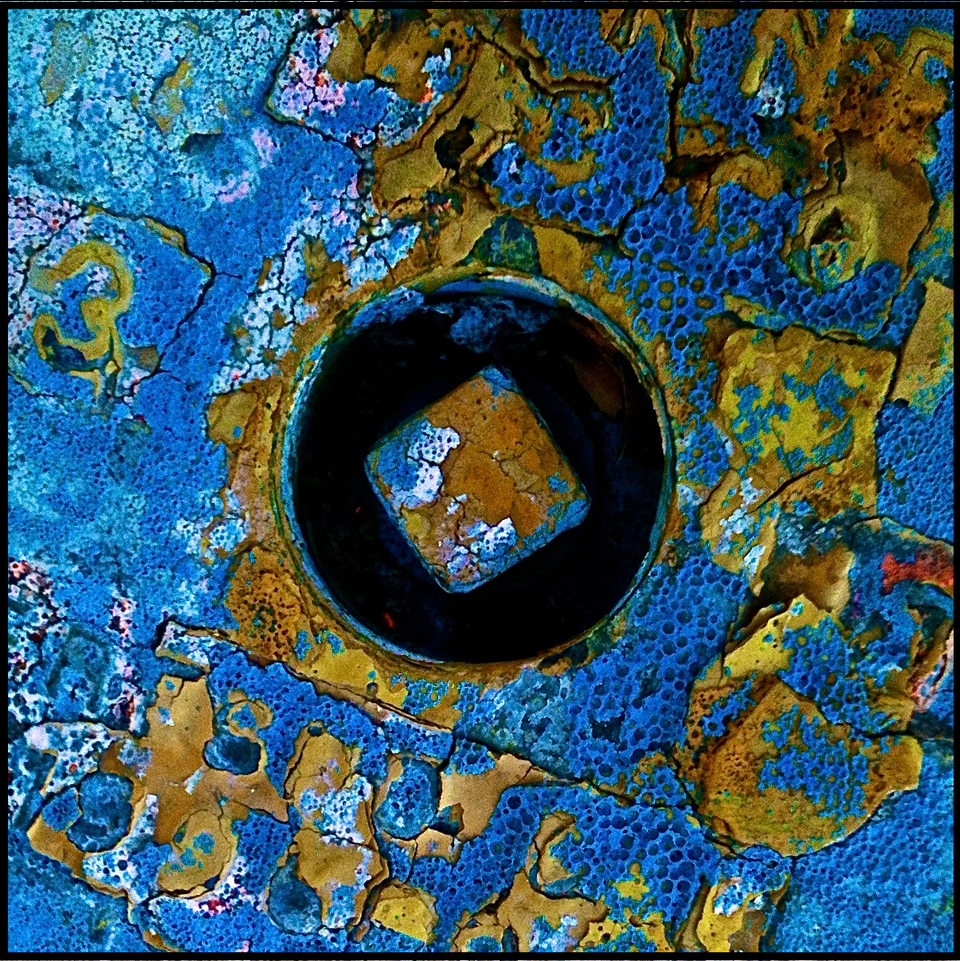

I get around in a wheelchair. One day years ago, one of the front casters of my chair got pinned in a crack in the sidewalk, and I spilled out onto the ground. During the fall, the iPhone that I keep in my jacket pocket somehow managed to take a photo of its own accord, a photo of, well, nothing much. The image that popped up on the screen that day interested me in its blurred mundanity. I soon began taking photos of the world that surrounds me from this particular angle of a wheelchair, an angle that looks up at the lower third of the horizon or looks down at the ground, unlocking the closed door of distant close-ups.

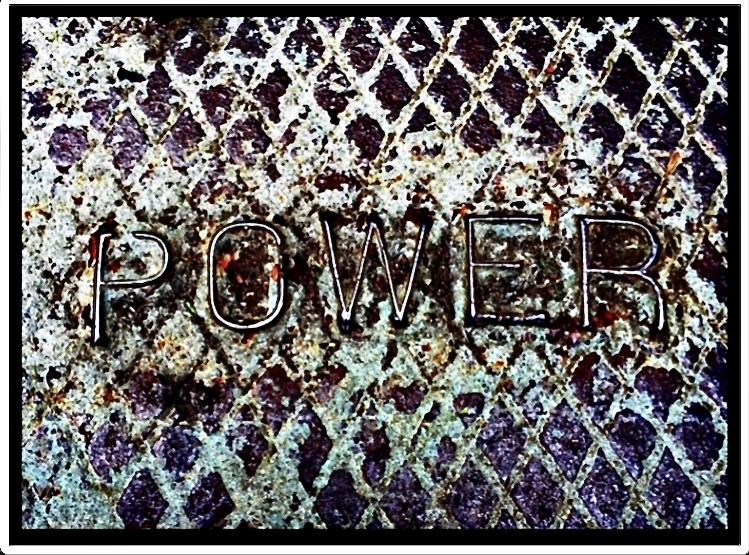

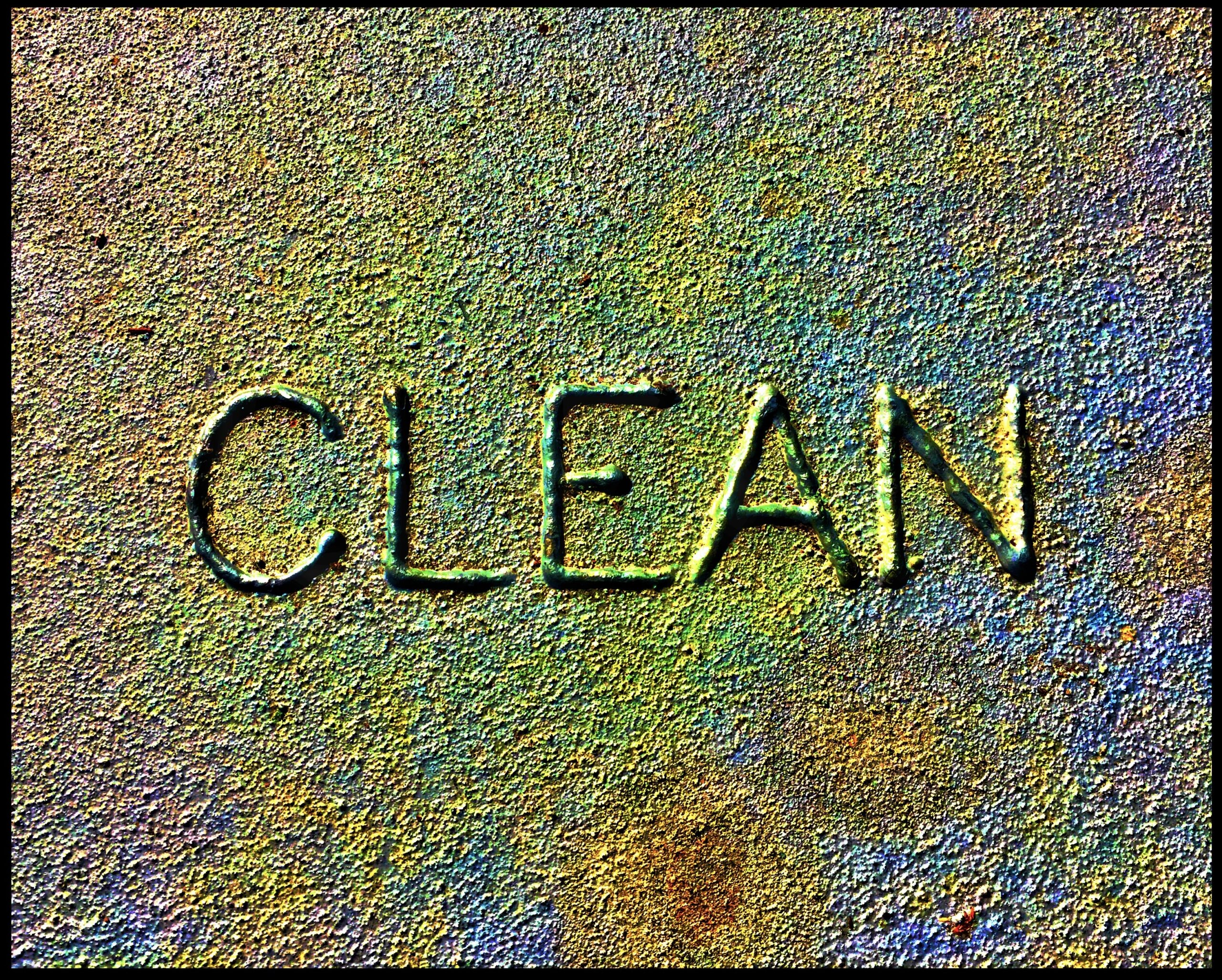

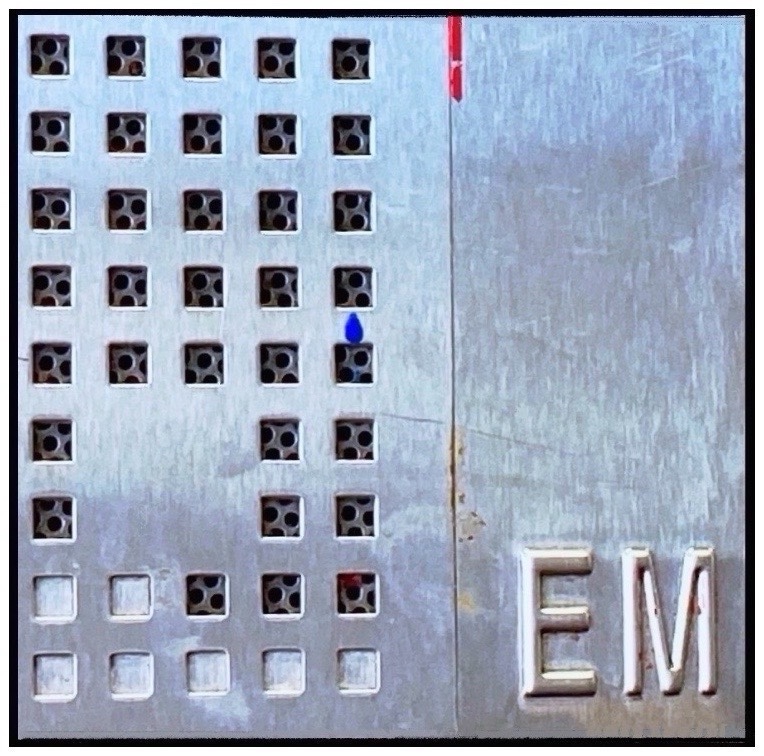

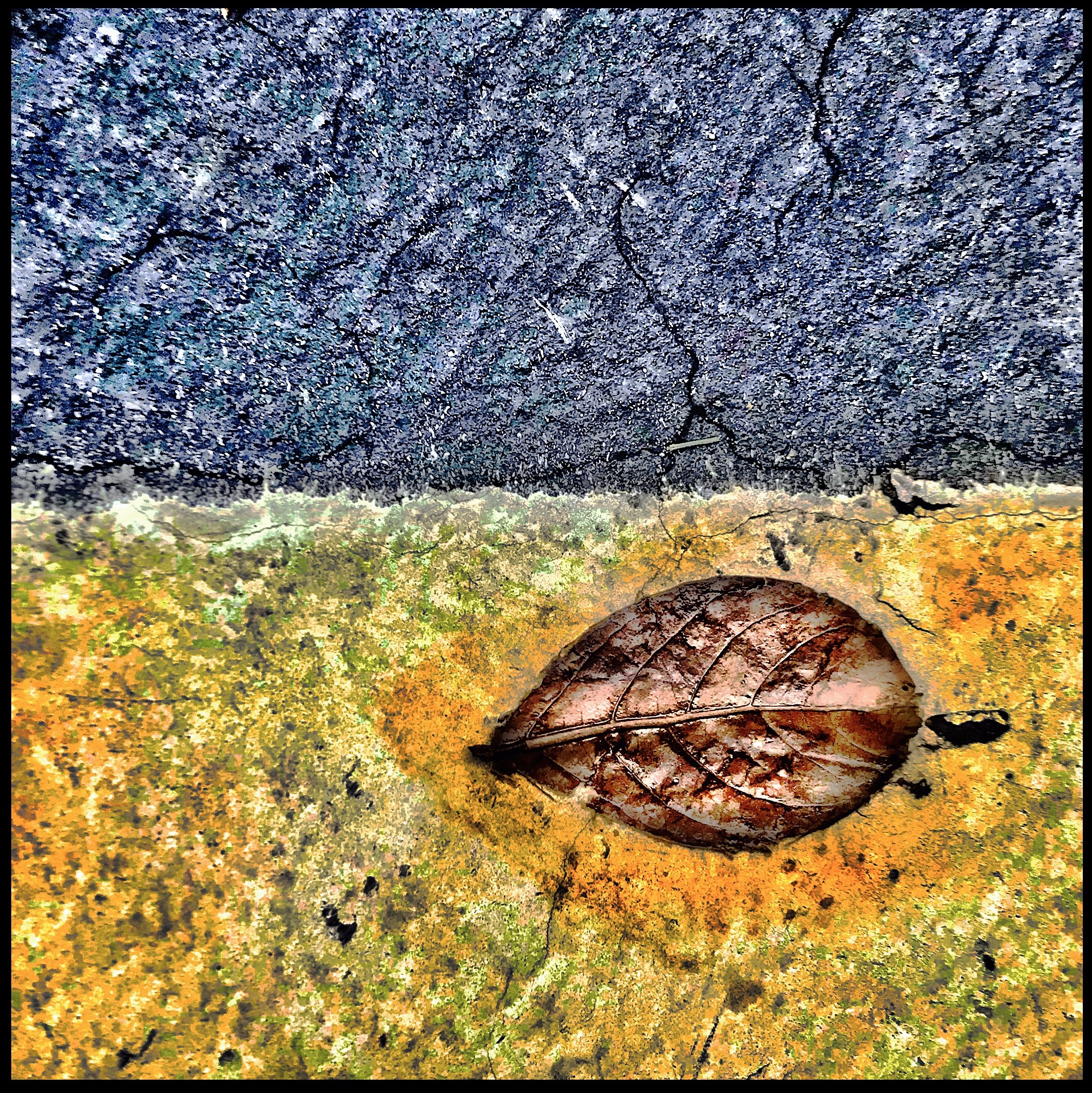

I’m continually finding something of interest in the red wheelbarrow of the commonly unseen. The photograph as artifact: peeled paint, pigeon droppings, spilled detritus. History gone broke. As a poet, sometimes my photographer’s eye is particularly drawn to the word world—letters etched on the sewer cover, the stenciled curb, the label on the stanchion. “A poem is a small (or large) machine made of words,” writes William Carlos Williams. A poem results from craft, not sentiment. While some may find this concept difficult, it’s actually quite simple. My photographs encourage the viewer to look at the text rather than through it—to notice composition, color, light, and shadow, rather than plot.

In the words of Ezra Pound, my photos hope to “make it new.” Like my writing, my photos grow out of the experimental interests of the modernists, the New York School, the Objectivists, and the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets. These avant-garde artists challenge expectations of genre, syntax, and meaning. All these poets focus upon the word as a thing, upon the notion that the writing on the page simply is what it is. My photographs expect nothing of the viewer other than to experience the sensory present, which might or might not be framed in the context of their own imagined past, hopes, or fears of the future. Often decontextualized extreme close-ups, the photos aim to challenge a system in which the viewer’s eye moves left to right, top to bottom, clockwise. The text—photograph or poem, thus tends to be non-linear and non-representational, simultaneous.

In orchestration—how does this poem sound, how does this line connect to that one, how do the connotations of this word expand that allusion into the infinity; how does the photo reveal in a gesture the texture, the shade, the shifted shape? With the close-up the abstract made concrete:

The way

the things

Upon one

another bear.

The photos flinging us into the mix of intention and happenstance, the transient beauty in the shapes we adore, and the stuff we toss away. If an iota of rust can draw us to attention, then mathematically this means our awakening may be 10,000 times more of a wilderness than we believe. The photos ask us for a moment to hear a note of silence in the traffic . . .

Zooming in on the particulars, as we see in my recent book, There There Now, my work often grows out of the rhetorical tropes of framing, synecdoche, and juxtaposition. As opposed to seeking a relation to nostalgia, the photos and poems in the book arise from the all-around noise of our immediate existence. The fact of the photograph reflects the Japanese concept of “wabi-sabi,” or “the beautiful in the ugly.” The quotidian images of the ground, of rusted pipes, of brackets and keyholes, spent exposure. I’m not especially interested in registering the everyday comings and goings of humans. I figure that humans have had their say at this point, having crashed the natural environment: the Earth’s last gasp. Humans, after all, elected Donald Trump as the reckless dictator. The big, beautiful bill; the mad chainsaw, staged. Ukraine, Russia, Gaza, Israel. Artificial intelligence, enforced ignorance, the death of education.

What will it take to unhinge this dirt? The sound of the projection machine, black and white, a blaze of color. These silent “talkies” at last report record the paradox of objects. Snapped off the wrecked wheelchair, what beauty remains in the asphalt, now, after the marks and scars?

In remembrance of Sebastião Salgado (1944-2025) and Fanny Howe (1940-2025).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Scott D. Bentley is a poet and photographer based in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he teaches writing at California State University East Bay. Often printing on metal or fabric as well as paper, he explores how the abstract becomes real through touch and decay. Bentley is the author of several poetry collections, including EDGE and Ground Air, and his recent hybrid works—There There Now and All Around Noise—bring together his photographs and poems in striking harmony.

Ramsay Breslin

July 29, 2025 at 18:07

Gorgeous photographs and compelling, beautifully conceived and honestly felt sentences. Thank you for this illuminating window into your work. I would only add that for me what “simply is” in your work often startles me with its spatial complexity. Those photographs that are seemingly “simpler” and more apparent as surface expressions, reflect the intelligence and vigor of your consciousness, as if by design, in terms of color, texture, shape, and so on, just as you say.

Scott Bentley

October 24, 2025 at 18:49

“Simple vigor,” shall we say? Thanks , Ramsay.

Carla Denim

July 30, 2025 at 00:28

Amazing images that ask the viewer to look so much more closely at the “world that surrounds,” the quotidian, the wabi sabi. And I love the connections between poetry and photography.

Scott

July 30, 2025 at 17:40

Thank you, Carla. I’m glad you enjoy the connections between.

Kristin Anderson

July 30, 2025 at 00:33

Wow. Love this piece AND the gorgeous photos.

Scott

July 30, 2025 at 17:42

Thank you.

Scott

July 30, 2025 at 02:04

Ramsay,

Thank you for your kind, detailed response. I knew—darn!—that that “simple” line was going to get me into trouble. I didn’t mean to suggest that the making was simple or haphazard; I meant to claim that what the viewer sees is relatively simple: a photo made of light, shadow, shape, hue, etc. What happens after that in the viewer’s experience of the design is not of my particular concern in that it becomes beyond my control. In other words, the photos, for the most part are not “of” anything or “about” anything that we ought to spend much time together trying to name.

One thing in your comment that I wonder if you might have something further to say (or not): I wonder why you named the “essai” as “sentences” rather than, say, “prose” or “argument.”

Tom Killion

July 30, 2025 at 05:13

Your writing dances along like a full-blown 70s punk show. I want all the photos streaming along with it in a big light show. When or where can we all photos evoked by your words? do exciting and glorious!

Scott

July 30, 2025 at 17:44

Wow, a light show! Let’s get Bob Geldof on the project

Olivier

August 2, 2025 at 19:22

Great ideas fall upon us by accident(s) and Scott’s images are no exceptions! They are however not only the effects of chance but, like his words, of cautious carving. Great job, please so continue!

Scott

August 2, 2025 at 21:26

“Cautious carving”! Bro, that’s one helluva sentence.

Tom Wilson

August 3, 2025 at 01:41

In the moment between a couple of work things, and with weekend house guests and their dog to entertain, I thought I’d do a quick read to fill in the time, but what I found, however, demanded much more of my attention. I, too, tripped over your “simply” reference, Scott, as I’ve never found anything simple in your photography, but rather a series of thought-provoking images that have challenged my own work over these last few FRAMES years and been a source of ongoing inspiration. I’ll come back to this article, perhaps a few times, when I have more time to spend with it … but for now please know that I’ve enjoyed the photographs, the story and the creative intelligence behind it. Thanks for sharing it with us and best regards.

Scott

August 4, 2025 at 10:16

Thank you so much, Tom. I so appreciate your kind words.

Pasquale Verdicchio

August 3, 2025 at 05:29

Wow! Scott… the photos, the writing … both explode with color and nuance… making it new indeed … over and over!

Scott

August 3, 2025 at 09:03

Thanks, coach.

Frank Styburski

August 4, 2025 at 18:10

Delicious images, Scott! I just want to eat them up with my eyes and get fat from their visual wonderfulness. I’ve been a fan of your work since we met on the FRAMES Facebook photo group in 2021. I think that we share a similar aesthetic when it comes to photography and often wish that I had taken the pictures that you post. I’m sorry I didn’t, but glad that you did and share them with us to enjoy.

Nice work, man!

Scott

August 4, 2025 at 20:35

Thanks so much, Frank! Big fan of yours, too. Maybe someday we’ll have a photo-eating contest!

M H Santelli

August 4, 2025 at 18:50

Nice prose, nice photos!

Scott

August 6, 2025 at 03:20

Thank you.