The discovery was a surprise.

I was rummaging around the detritus in the bottom of an old camera bag, various empty lens filter cases, air puffers, instruction manuals for things I was unaware I ever owned, wondering about my own photographic history, trying to gather hardware to sell. I had shuffled this camera bag from home to home for more than three decades, and I vaguely remembered what camera was inside, a Minolta X-370 with a couple lenses, but little more. So when my hand came around an old grey plastic film canister, I wasn’t terribly surprised.

But then I opened it.

Inside, there was a roll of unexposed Kodak Tri-X film. Tri-X is nothing special, of course. Or, to be more precise, it’s something extraordinary that’s also common. And I would argue that anybody who’s ever shot film has shot at least one roll of Tri-X. I am old enough to remember when 400 speed film was sexy as hell. Yet, although I could buy a roll of brand new Tri-X today, what I held in my hand was at least 30 years old.

I felt like I was holding a secret.

There is an allure to old film. There is a kind of archaeological or ethnographic appeal when we discover film that’s been exposed but not developed, a kind of time-capsule attraction. Yes, we admit while cringing, that’s what we used to wear. We get to see our past lives and the past lives of others revealed, as if opening in ancient tomb. This is who we were.

We have so much interest in discovering our past, and so much need for preserving it, that Ron Haviv with Lauren Walsh established the Lost Rolls America project. According to their website, “The Lost Rolls America project opens the magical reencounter with the past to anyone who possesses unprocessed film rolls. Contributors provide one roll of film, which is developed and scanned free of charge by FUJIFILM North America Corporation, and made available back to them. Participants then choose one image and, in a small write-up, explore the meaning of the photo and the significance of re-viewing a piece of their personal, sometimes lost past. Ultimately, these observations offer points of identification, through descriptions of similar memories or associations, for other viewers of this collective experience.”

But what about old film that has not been exposed? Would the old sensitivity say something new about today? Would the film still be able to capture an image? There is the cliche about the future being unwritten and we can make of it whatever our ambitions and talents allow. But what about history? Can we write the present onto the past? There are lots of old cameras out there, and plenty of old processes still being used. But this was different. This was 2022 being written upon 1985.

I wrote to Lauren Walsh, Director of Lost Rolls America, asking for help dating the film. She, in turn, asked, Sofia Adams, a filmmaker who, as the Lost Rolls producer, helps to maintain the archive, who said, “Because the ISO is 400, that means it was created after 1960 (they switched from ISO 200 to 400 then) but that still doesn’t narrow it down much. Because it’s listed on the packaging as TX-400 that means it was made before 2002, when they switched to writing it as 400TX. So not super useful, but I think it was produced between the year 1960 and 2002.”

The Minolta X-370 was built from 1984 to 1990. Knowing my own history, and assuming the roll and the camera were onetime meant for each other, I decided the roll was most likely from 1987.

A 35 year old roll of unexpected, unexposed film is an exciting idea. I had not shot film for a very long time. All of my habits were based around a digital experience. Everything from composition, to number of shots, to bracketing, to you name it, was based upon the idea that I have limitless opportunity. Even if my battery or memory card ran out of space, all I needed to do is pop in another one. What I had lost was the visceral feeling of the value of a single potential image.

If I tell you I could not resist, I would be wrong. That would imply I wanted to resist. I did not. In fact, I could not wait to load the old film in my old camera and go exploring.

I enlisted three friends whose photographic work I admire. Here’s a roll of old film, I said. I have no idea if it’s any good. But let’s assume it is. (Lauren also said, “A 30 year old roll of B&W should be pretty stable – unless you kept it on top of a heater for all this time!”) If you’ve only got four or five shots. what would you take? They all jumped at the chance.

I turned to the Internet, which had all sorts of advice regarding old film, tricks for tweaking ISO settings and such, but all the advice boiled down to one sentiment: Good luck.

My old X-370, which weighs as much as my car, was in fine working order, although the batteries for the light meter were dead. I did not replace them and handed the camera to my friend Ross Collins. Then Dan Koeck. Then Jon Solinger. Then me.

“I tried to look at two different things,” Ross said. “I tried to imagine what I would have shot back in the day, when this stuff was new, and I wanted to do something a bit more abstract. It had been at least fifteen years since I last shot black and white film. I think I probably shot my last Tri-X in 2005.”

“I learned to shoot with slide film,” Dan said. “I bought a Pentax from the PX in Japan when I was in the Navy, loaded a roll of slide film and started shooting around the ship, and then went downtown with a friend. We went around like tourists. I remember, vividly, saying now don’t go spending money on lenses and don’t get carried away with this photography. But after a few months I caught the bug.”

“When I was in college studying photography,” Dan continued, “I really enjoyed the street shooters, people like Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson. I really liked that style and that’s always been a part of my style as well. So when offered the chance to shoot black and white film, I thought street photography. I went downtown and just started walking around, hoping to get a gritty black and white shot.”

“Was there something about the fact that you were shooting film versus digital that changed your approach?” I asked.

“Not really. I have the same thing in mind when I shoot digital. It’s more who I am and not about the camera. But I can’t deny the influence that Tri-X has, that look of contrast, the gritty kind of feel. That look of street scenes that other photographers made famous is a part of who I am.”

“I still shoot film today,” Jon said. “I didn’t shoot film for a long time, but last year I picked up the film camera again because I had access to a darkroom. I got excited about it and now I’m also excited about getting my old darkroom up and running again.”

“Do you do you see a big difference in your attitude between film and digital?” I asked.

“I kind of like the restraints of it, or the limits. Especially for black and white. It’s kind of like writing a poem in a certain form, where you have these limits. You’re working in a way that makes you more conscious, where you’re really thinking about what you’re doing. And you have a different time sense because you’re shooting things and you just don’t know what happened till much later. I find that interesting because it makes me more thoughtful.”

I waited. The camera and the film were out of my hands. I spent hours imagining the old school new again. Then the camera came back to me. And what struck me first, holding the camera in my hand and realizing I had four, and only four shots, was not a sense of creativity. It was a sense of fear. I am quite accustomed to taking a picture, immediately reviewing it, realizing what I may have done wrong, and taking it again. As most of my work these days is street photography, I find a certain level of freedom to experiment in the fact I can shoot an unlimited number of pictures and trust I will discover in post processing all sorts of gems.

I found myself stymied by the value of the potential. There was this sense of care for the single image that I remembered, but had not felt in a very long time. Every shot mattered. There was no room for error.

Let me say it again. I was afraid. Afraid of wasting a potential. So I decided to do still life photography in my office. Still life allowed me the opportunity to carefully meter and compose. Still life allowed me to practice patience and forethought. It really didn’t matter that I’m no good at still life photography. I had not approached the single frame this way in a very long time.

When the roll was finished (what a wonderful and terrible feeling it is to move the film-advance lever and feel it resist at the end of a roll!), Ross offered to develop the negatives. Then he discovered his package of T-Max, like the film, was well out of date. He ordered some new from Amazon, which showed up crushed and leaking, then ordered some more, which arrived intact, and the whole roll turned out nicely. I marveled at how valuable a roll of negatives felt in my hand.

Dan owns a digital scanner and made a contact sheet for all of us to review. No enlarger and no tubs of developer and stop bath. Digital scans emailed to the four of us. Old school and new school together.

My own reaction, the seeing the images, was twofold. First, a contact sheet! Not a real one, of course. But close enough. I love those things. In my early days with digital, I used to look for post-production templates which would allow me to simulate a contact sheet for a series of thumbnails. And I discovered I no longer own a loupe, which would have been silly because the contact sheet was on my computer monitor.

Second, scanning through my images, I wondered what I was thinking. When a digital file appears on my screen, it’s a starting point. A rough draft. I know I will adjust the crop, the texture, the sharpness. Looking at the contact sheet, every frame had a sense of finality and weight, and I was not happy. So much for getting it right in-camera.

Nonetheless, all of us selected one image from our set of four or five. Dan scanned those, sent them to us, and each to our own sense of taste ran them through Lightroom or Photoshop.

Again, no enlarger. No little red lightbulb stuck high up on some wall. But the sense of old school was hanging in the air.

“I realized afterwards,” Ross said, “that I had changed my mentality toward thinking I could just fix it up in Photoshop. If you followed the old way and went to a darkroom, you could dodge and burn and crop a little, but you didn’t have the kind of controls that we presume today, and take for granted. There is a reason why we went to digital. I would have rejected this much grain in the old days. I presume it was because of the old film.”

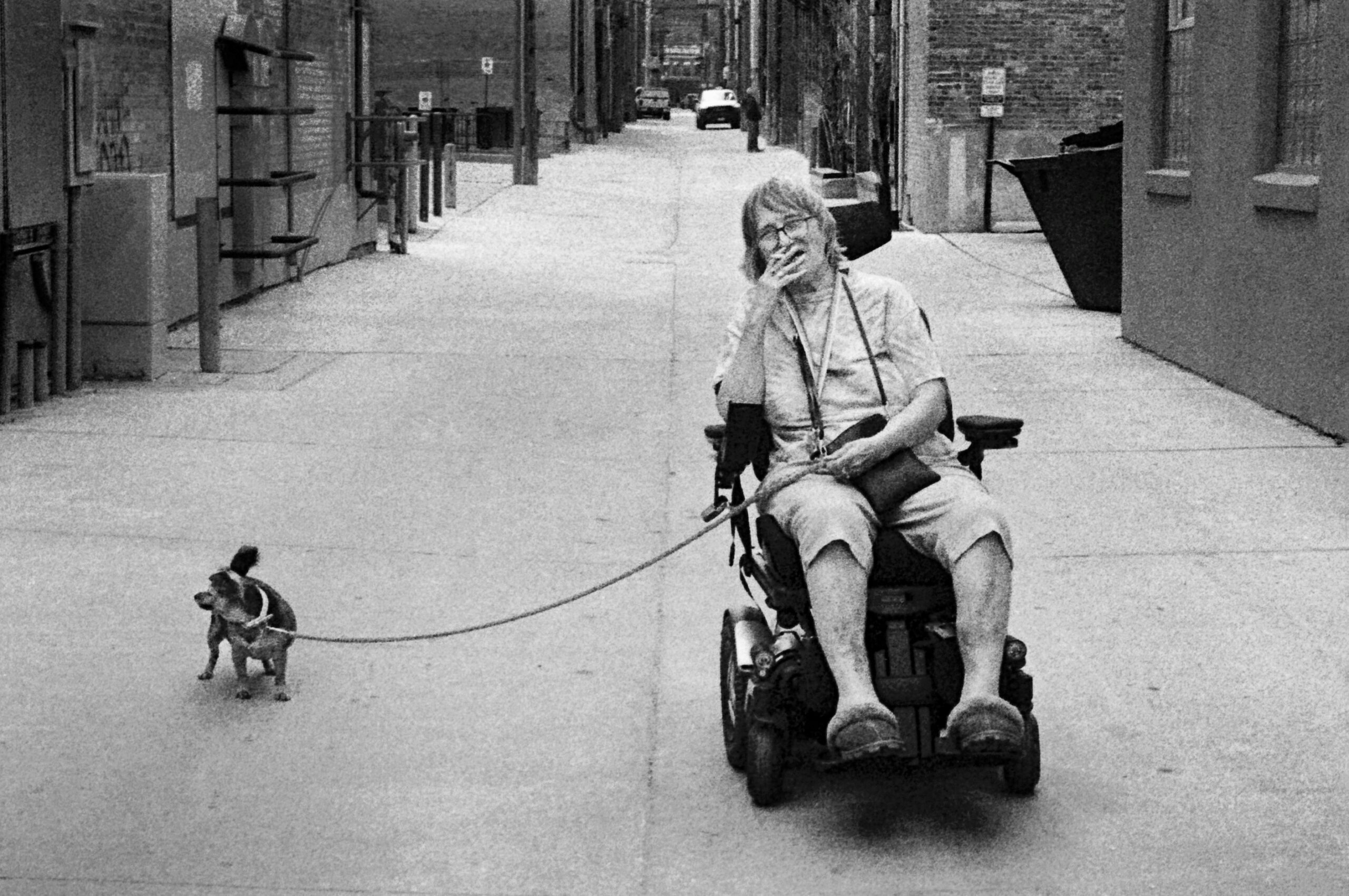

“We only had a few shots,” Dan said, “and I think my best work is photographing people. I ran into a woman who was in a motorized wheelchair with her dog. She was smoking, which added to that personality. I had trouble with the exposure but the thing about Tri-X is you’ve got a lot of latitude. Yet I’m never totally happy. If I had just stepped two paces to the right, her head would have been framed by the concrete. I kind of wish I done it differently.”

“If you were shooting digital, would you have done a quick review and then re-reshot?” I asked.

“Yes. That’s a good point. Digital would have helped in that situation.”

Jon added, “I was thinking about composition quite a bit. I was thinking about how to make an interesting picture out of things that are visually interesting to me, so it’s sort of a translation project. I can’t win them all, but I think a couple were nice and it was fun because there’s always an element of surprise. When you’re in the three dimensional color world, your brain says one thing and then what you see in the translation into this two dimensional black and white world is sometimes things you didn’t see when you were there.”

My own image of a model airplane is alright. It’s not going to win any awards, but I can say it changed a great deal in my head. Shooting film forced me to remember a sense of care I had forgotten. I suppose if I did landscape work with a tripod, or astral photography, or a thousand other forms, I might have maintained this sense of uniqueness. But my photographic subjects are all bound up with speed and the fleeting moment, so this new/old endeavor was a reminder of foundations.

Did old film say anything new about today? Did the old school share some insight, in terms of the image, I had not imagined? No. But did the old school remind me about something deeper, something about the way we approach the art, I had neglected? Yes.

So this much is true. Tonight, when I head out to see what adventures wait downtown, I might walk as quickly but I will be more intentional, and more caring about each frame, and this will be a good habit to restore.

“One other thing,” Dan said.

“Yes?”

“I made a print for that lady. A physical print. I gave it to her and oh man she was thrilled.”

LINKS

LOST ROLLS AMERICA

ROSS COLLINS

DON KOECK

JON SOLLINGER

W. SCOTT OLSEN

Drake

November 18, 2023 at 17:09

I’m sorely tempted to buy my first role of film in 20+ years. I still have my 1976-ish Nikkormat. I think it still works. I’m a much better photographer then I was, but I share your sense of trepidation. I don’t want to disappoint myself.

“I felt like I was l holding a secret.” Heartful and vivid.