Jacob Riis is widely acknowledged as a social activist and a groundbreaking documentary photographer who, in the late 19th century, exposed the squalor of the slums on the Lower East Side of New York. In his impassioned advocacy for better housing design and educational opportunities for the immigrant poor, he became one of the most famous men in America. What is less recognized is that he viewed his subjects through a profoundly racist lens. It’s time to reexamine the legacy of, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, New York’s “most useful citizen.”

For a number of years. I’ve led a class at the International Center of Photography on photographing the Lower East Side of New York. The students take pictures of the neighborhood, cognizant of the rich history of the neighborhood as portal to America, and we assemble a book that is presented to the ICP library. In many ways, the history of photographing the Lower East Side closely follows the history of photography in general. Many of the most important innovators of the medium lived or worked in the neighborhood. The list includes Lewis Hine, Paul Strand, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Weegee, Helen Levitt, Walter Rosenblum, and recently, Nan Goldin. The names go on and on, but the story always starts with Jacob Riis, the Danish immigrant, whose beat as a police reporter covered the Lower East Side.

His photographs are blunt and unflinching, almost anonymous in style, attributes that, in the 1960s and 70s when his work was rediscovered by a new generation of scholars, helped usher him into the canon of art photography. John Szarkowski, photo curator at the Museum of Modern Art, featured his work in “Looking at Photographs,” published in 1973, and in an essay in Artforum in 1981, Colin Westerbeck writes: “The paradox of Riis’ posthumous reputation is that photographers now make art by doing what he did in order not to make art.”

Riis made photographs primarily to accompany his newspaper writing and to provide illustrations for his lantern slide lectures, in which he shocked his middle-class audiences with images of people living amidst filth and crime, and what he described as moral depravity brought on by poverty and cramped tenement housing. Riis focused especially on the dark and airless rooms of typical Lower East Side dwellings, and promoted the development of more humane “model tenements.” He was a religious zealot – or, to use his own word, a crank – on a crusade to right society’s wrongs. And he made a difference. His hectoring criticism of tenement landlords led to better housing design, and his concern for the education of children led to the creation of settlement houses that provided a wide array of social services. At the same time, however, he gave scant attention to the labor movement of the late 19th century and preferred Christian charity to a progressive reordering of society.

His crowning achievement was the book “How the Other Half Lives,” published in 1890, which was among the first publications in history to combine text and photographs. It was a best seller and made its author famous, if not rich. It was also a luridly written extended essay of “scientific” observations about the myriad ethnicities occupying Lower Manhattan. “One may find for the asking an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony. Even the Arab, who peddles “holy earth” from the Battery as a direct importation from Jerusalem, has his exclusive preserves at the lower end of Washington Street. The one thing you shall vainly ask for in the chief city of America is a distinctively American community. There is none; certainly not among the tenements.”

Each group’s appearances and cultural attributes are described in detail. “With all his conspicuous faults, the swarthy Italian immigrant has his redeeming traits. He is as honest as he is hot-headed.” “…I state it in advance as my opinion, based on the steady observation of years, that all attempts to make an effective Christian of John Chinaman will remain abortive in this generation; of the next I have, if anything, less hope.“ Of Jews, Riis writes: “Money is their God. Life itself is of little value compared with even the leanest bank account.” And Blacks: “The poorest negro housekeeper’s room in New York is bright with gaily-colored prints of his beloved “Abe Linkum,” General Grant, President Garfield, Mrs. Cleveland, and other national celebrities, and cheery with flowers and singing birds.”

Riis was, it should be pointed out, sympathetic to the fate of Blacks after the Civil War, and states succinctly: “If, when the account is made up between the races, it shall be claimed that he falls short of the result to be expected from twenty-five years of freedom, it may be well to turn to the other side of the ledger and see how much of the blame is borne by the prejudice and greed that have kept him from rising under a burden of responsibility to which he could hardly be equal.” Nevertheless, “How the Other Half Lives” is a tough slog, page after page of the vilest stereotypes and judgments on human character.

This brings us to his photographs, the principal reason for our continued interest in Riis. The great irony is that Riis did not consider himself a photographer, nor did he think his images were of particular aesthetic value. Some of his photographs were even made by assistants or hired guns. They served a purpose, nothing more. Lantern slides for his lectures were the primary use, as halftone screening for printing in magazines and newspapers did not become practical until near the end of his life. Riis did not make photographic prints for display, and certainly, no gallery or museum would have considered his work appropriate for their walls. When he donated his archive to the Library of Congress at the end of his life, it included his books and essays but, significantly, no photographs.

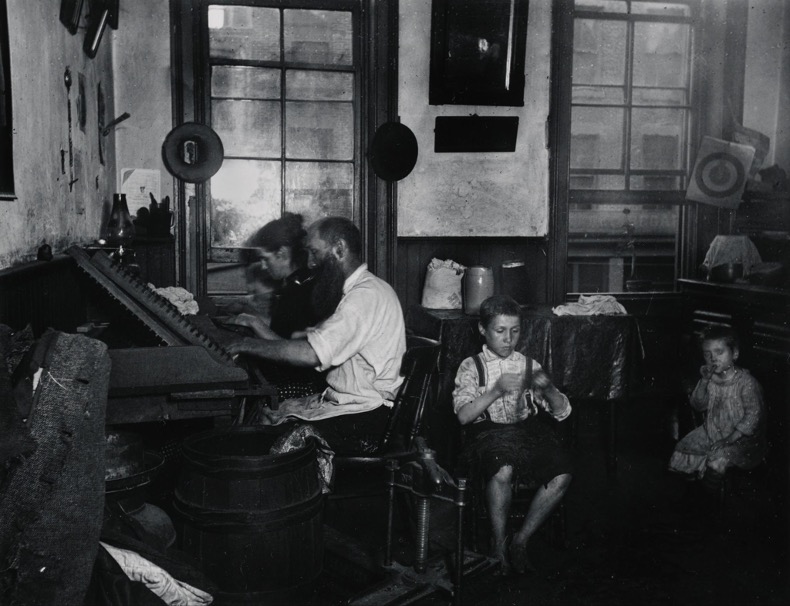

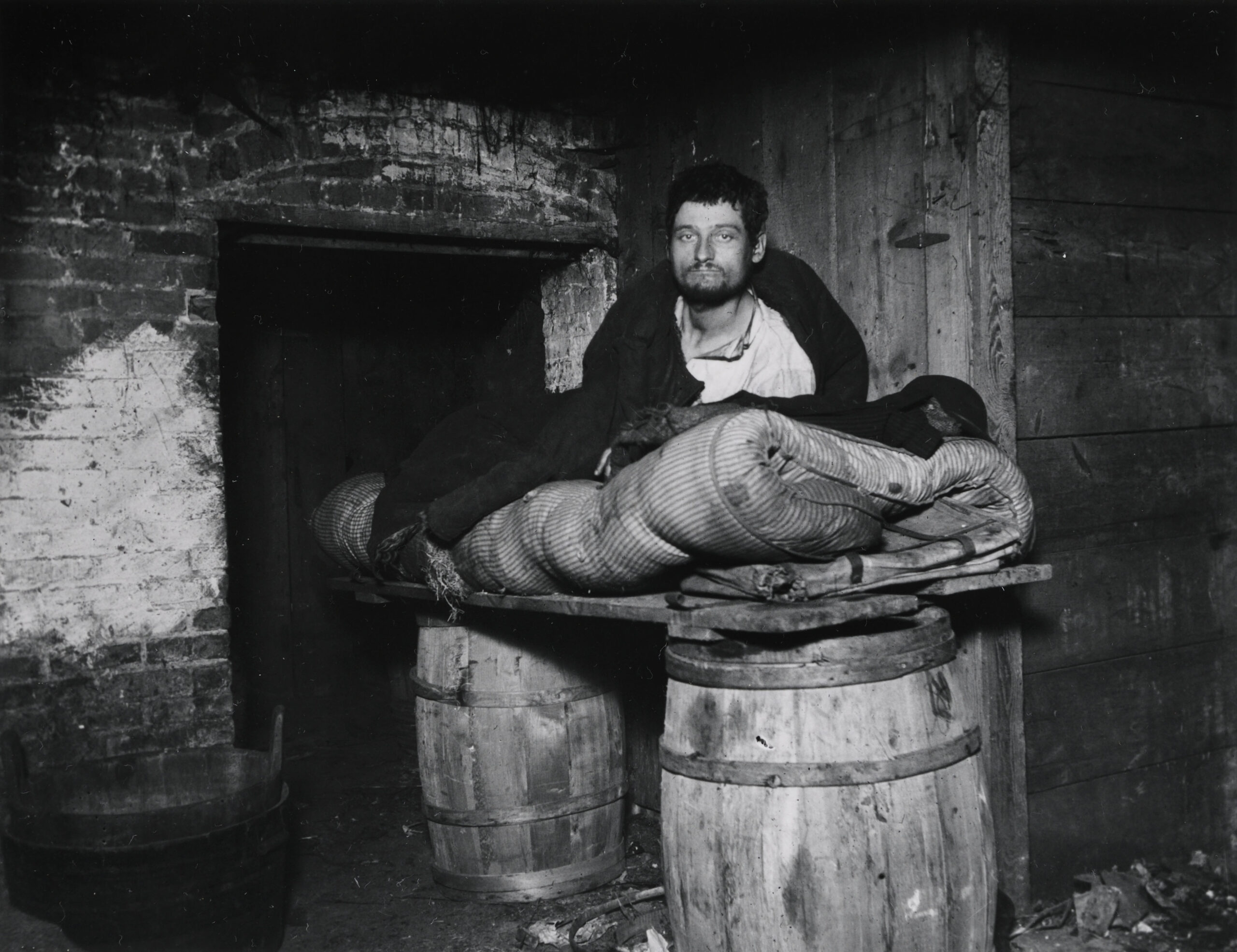

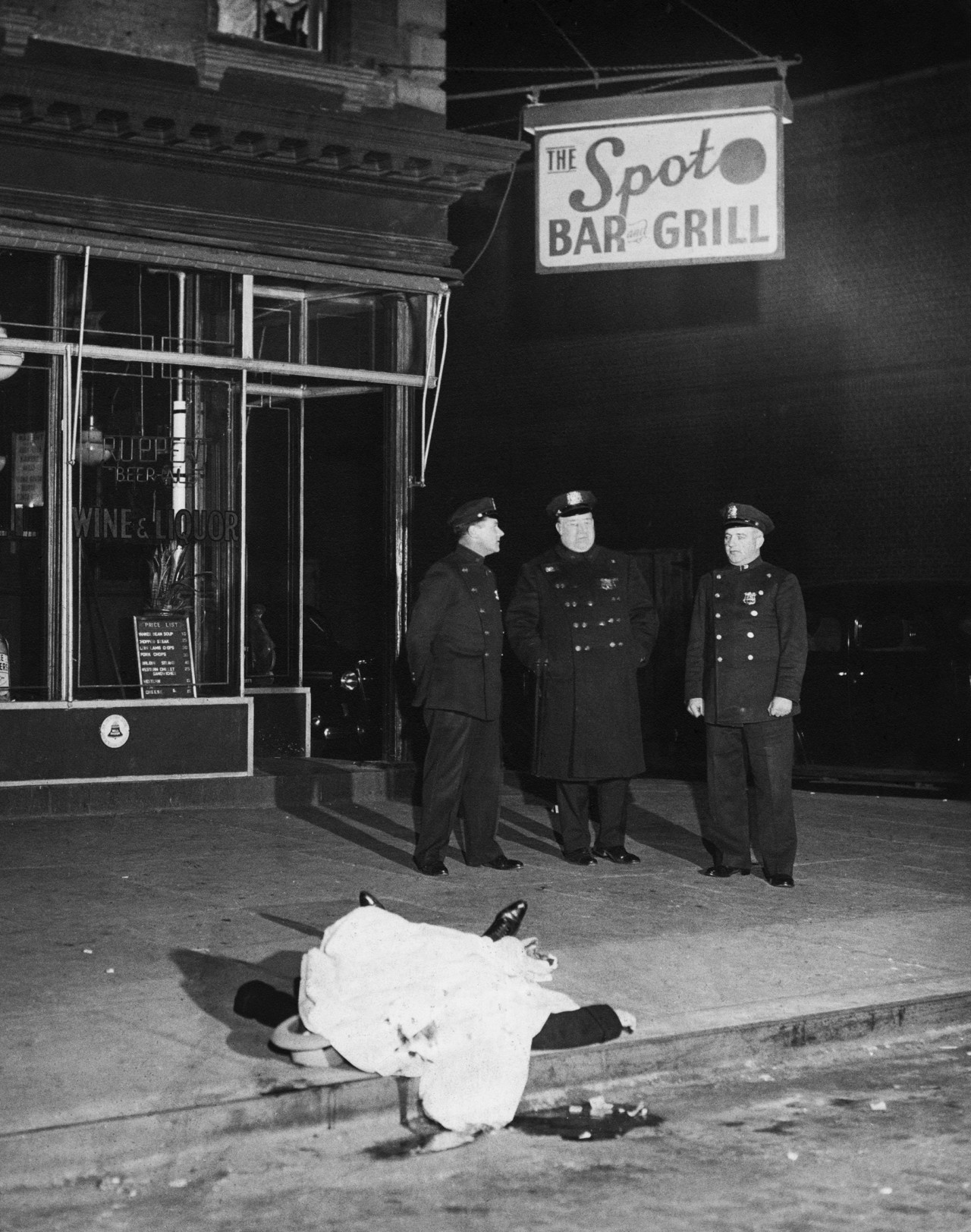

Riis’ great technical innovation was the utilization of flash powder to penetrate the gloom of tenement apartments, bars, opium dens, and flophouses. Since he was a police reporter, one imagines him arriving with an escort of cops from the downtown Mulberry Street station rapping on doors with their billy clubs and barking orders to open up. Riis and his assistants would bustle about, setting up their glass plate camera, followed by a blinding explosion of light revealing stunned individuals frozen in their nocturnal lairs. Outdoors, Riis clearly orchestrated many of his compositions, undoubtedly positioning people in the frame. One of his most famous images, “Bandits Roost,” has the look of a theatrical set, with a dozen rough-looking figures distributed throughout a narrow alley beneath a cascade of laundry flapping in the breeze. It’s a memorable image. But in general, Riis portrays people as victims rather than individuals who have agency over their own lives.

For all of Riis’ concerns about human degradation in the slums, he made callous use of people trapped by circumstances to further his aims. He appeared to have no qualms about invading their spaces, disrupting family lives, and violating personal autonomy. Riis was a showman as well as a reformer – his lectures were intended to entertain – and there is a straight line from his work in the late 19th century to Weegee in the 20th, who was also a press photographer who pursued the denizens of the night with his camera, especially on the Lower East Side. But Weegee was hardly a reformer and understood, first and foremost, that sensationalism sells newspapers. He was a populist carny – but more than exploiting the victims of crime; he exploited us – brilliantly. Riis, in contrast, was a stern and pious scold.

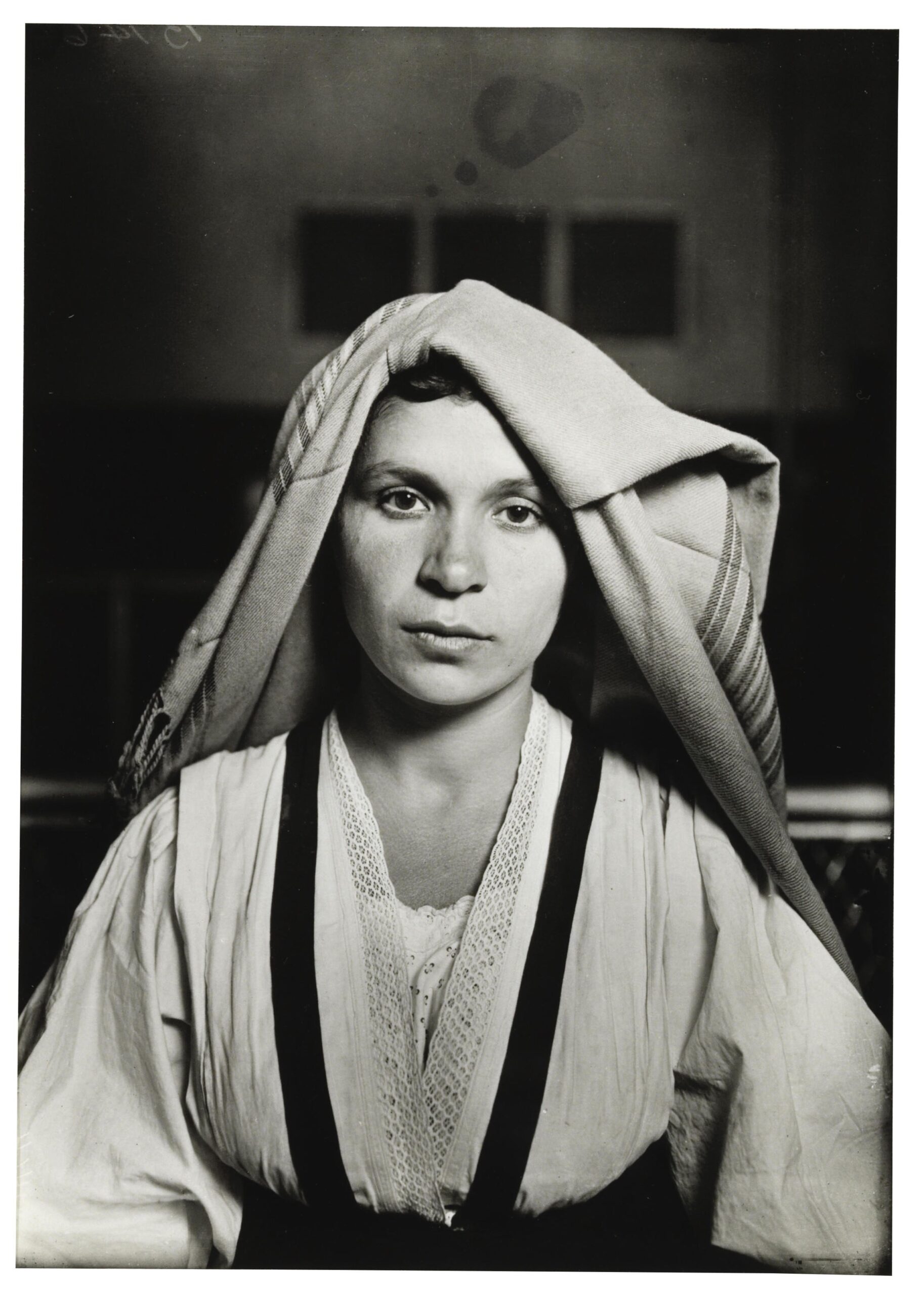

In my class at ICP, I compare Riis to Lewis Hine, who followed in his footsteps on the Lower East Side and is best known for his photographs documenting child labor. Hine was equally engaged as a social reformer, but his portraits of people do not objectify his subjects the way Riis’ did. Hine’s images of newly arrived immigrants on Ellis Island convey the dignity and vulnerability of individuals fleeing from oppression or simply aspiring to a better life. Instead of Riis’ harsh magnesium flash, Hine was attentive to the glowing light that filtered through the arched windows of Ellis Island’s Great Hall, illuminating faces weary, worried, but hopeful. Many of the people Hine photographed undoubtedly ended up in the tenements that Riis condemned as evil on the Lower East Side, for better or worse. But one suspects that their fates were not always as bleak as depicted in Riis’ photographs.

Inevitably, in the act of photographing those who are disadvantaged or caught up in circumstances beyond their control, there is an unequal balance between photographer and subject. There is always a hint of exploitation. This is true of both photographers. But In Riis’ case, it is more than a hint. Photographers often deny it, but there is a degree of predation inherent in the act of making pictures. I think Weegee understood it when he said, “…you can’t be a nice nelly and do photography.” But even in warfare, there are certain rules of engagement. In Riis’ war on poverty, his subjects were often treated as nothing more than visual cannon fodder. There are exceptions, however. Riis’ beautiful image of three young women making direct eye contact with the photographer, described as election inspectors, shows what he might have done had he regarded photography as more than a didactic tool.

So, what do we do with Riis? I still intend to present his work to my class and discuss the issues I’ve touched on here. I think it is important to grapple with the fact that strong imagery and good intentions do not necessarily go hand in hand. Riis’ moral certitude provided him with what he must have considered adequate justification to intrude on others. And out of that sense of entitlement came a body of work that established the practice of documentary photography and photojournalism. Like it or not, we have to deal with it.

Jacob Riis was, to be frank, a self-righteous do-gooder, a Christian evangelist with a deeply racist outlook on those who occupied the crowded polyglot of the Lower East Side. And yet, for years, the consensus has been that he is a heroic figure. His saintly image began with President Theodore Roosevelt, who met and befriended Riis while getting started in New York politics. Roosevelt wrote:

“Recently a man, well qualified to pass judgment, alluded to Mr. Jacob A. Riis as “the most useful citizen of New York.” Those fellow citizens of Mr. Riis who best know his work will be most apt to agree with this statement. The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent ever encountered by them in New York City.”

The Jacob Riis Museum in Ribe, Denmark, his hometown, offers awards to young photographers whose images evoke the “spirit, vision, energy, and passion of Jacob A. Riis who believed photography was one of the most powerful ways to tell a story, provide hope, bring light to darkness, and educate and inspire people.” I’m not sure that Riis was exactly doing any of those things, though passionate he undoubtedly was.

There are parks and schools named for Riis, even a popular beach, and most notably in Manhattan, the Jacob Riis Houses on Avenue D on the Lower East Side, a collection of brick towers that replaced a former tenement and warehouse district along the East River. These buildings, and other projects like them, continue to provide much-needed low-income housing, but they came at the price of indiscriminate slum clearance and the brutal displacement of residents. The Jacob Riis Houses were products of the imagination of Robert Moses, the autocratic master planner who believed in the use of government to remake society. Like Riis, he tended to see people in the abstract rather than as the lifeblood of the city. Ironically, due to design principles inspired, in part, by the imperative for light and air – espoused by Riis and his followers – these monoliths on the East River have become symbols of low income housing gone awry.

So, I have an issue with Jacob Riis. It’s time we consider his legacy fully with all its contradictions and set the record straight. He was an important but highly problematic figure both as a social activist and as a photographer. And maybe – I haven’t made up my mind – it’s time to consider renaming those buildings on Avenue D.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in Virginia, Brian Rose moved to New York in 1977 to attend Cooper Union. In 1980 he photographed the Lower East Side, and in 1985 he began an extended project photographing the Iron Curtain and Berlin Wall. He has produced 10 books and his work has been collected by the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His most recent book Monument Avenue, is a documentation of the last days of the Confederate statues in Richmond, Virginia. He is currently working on a new project, Last Stop on this Train, which documents the neighborhoods around the ends of all of the subway lines in New York. Last Stop will be published by Circa Press and release is expected in March 2025.

Les Berkley

June 16, 2025 at 17:38

It’s the Princess Diana effect. She exemplifies the do-gooder with the ulterior motive, but it doesn’t matter to the kid in the Soudan who gets his face blown off by a mine, and then is sent to England or Japan for plastic surgery.

Rob Wilson

June 16, 2025 at 18:08

Fascinating article! I really enjoyed reading it.

I must admit that I never had more than a passing interest in Riis mainly because I don’t really like his images.

Thank you!

Tony

June 29, 2025 at 10:31

Though I don’t agree with quite a few positions taken in the article it is an excellent article. Riis probably was racist, most people are to one degree or another if they are honest with themselves, which few are and Riis use of stereo-types was possibly due to the fact that in most cases these fit and are recognised and acknowledge by most people, rightly or wrongly. Personally I think the real problem comes when you put words together with an image as it’s quite easy to steer people toward a particular position if you don’t let the Image speak for itself.