Said to be ‘Italy’s Cartier-Bresson’, Giovanni (Gianni) Berengo Gardin, Master chronicler of social and cultural life in post-war Italy, died on August 6 at the age of 94.

Born into fascist Italy in 1930, he grew up in the turbulent times preceding and during World War II, living in Rome with his mother, his father being held as a prisoner of war in India. This was when he had his first experiences with a camera, walking around Rome making photographs with his mother’s old Ica Halloh bellows camera. But these activities were cut short all too soon as all cameras were confiscated under the edict of the occupying German forces. After the war, and on the return of his father, the family moved to Venice, where the Berengo Gardin family ran a popular shop selling Murano glass and pearls.

His photography career started as an amateur in 1954 with submissions of his images to the magazine Il Mondo, a collaboration that lasted until 1969. Largely self-taught, Berengo Gardin learned his craft watching and working alongside other photographers during two years spent in Paris. At Les 30 x 40, Le Club Photographique de Paris, he befriended a number of the key photographers of the time, such as Robert Doisneau, Edouard Boubat, Daniel Masclet, and Willy Ronis. Despite later in his career becoming known widely as the ‘Italian Cartier-Bresson’, Berengo Gardin says in an interview with Black and White Magazine that it was working with Ronis, and not the French master, that had the greatest influence on his work, because by the time he came to know the latter only years later, his own approach to photography had already become established.

Driven by curiosity, his approach was calm, deliberate, observational, a practiced exponent of eye, heart, and brain working in unison to make the photograph. A flâneur seeking out his subjects as he wandered the various locations, he believed it was important to the interpretation of his photographs that a person be included in the frame; on those occasions when, for whatever reason, a person wasn’t there, the composition was such as to suggest a presence. A keen observer of people, waiting and watching, not so much to capture ‘the decisive moment’, but to capture life as it was: raw, unfiltered reality, which at times could be uncomfortable and disturbing. He documented, chronicled, and catalogued life in Italy during a period of economic growth and recovery as the country began to emerge from the darkness and privations of the war, showing a population experiencing an increasing freedom and changing culture. He photographed the people, not for themselves, but in the situations in which he observed them, recording life – humanity – as it was in those periods of rapid growth. In ‘Venezia 1958 – Spiaggia Di Malamocco’, we see a young couple lying and hugging intimately in the sand dunes on the beach on the Venice Lido. In the foreground are casually discarded clothing, shoes, and a vinyl record of recordings on the “La voce del Padrone” (His Master’s Voice) label, all of which convey a picture of relaxed freedom, independence, and abandon.

© Gianni Berengo Gardin/Contrasto

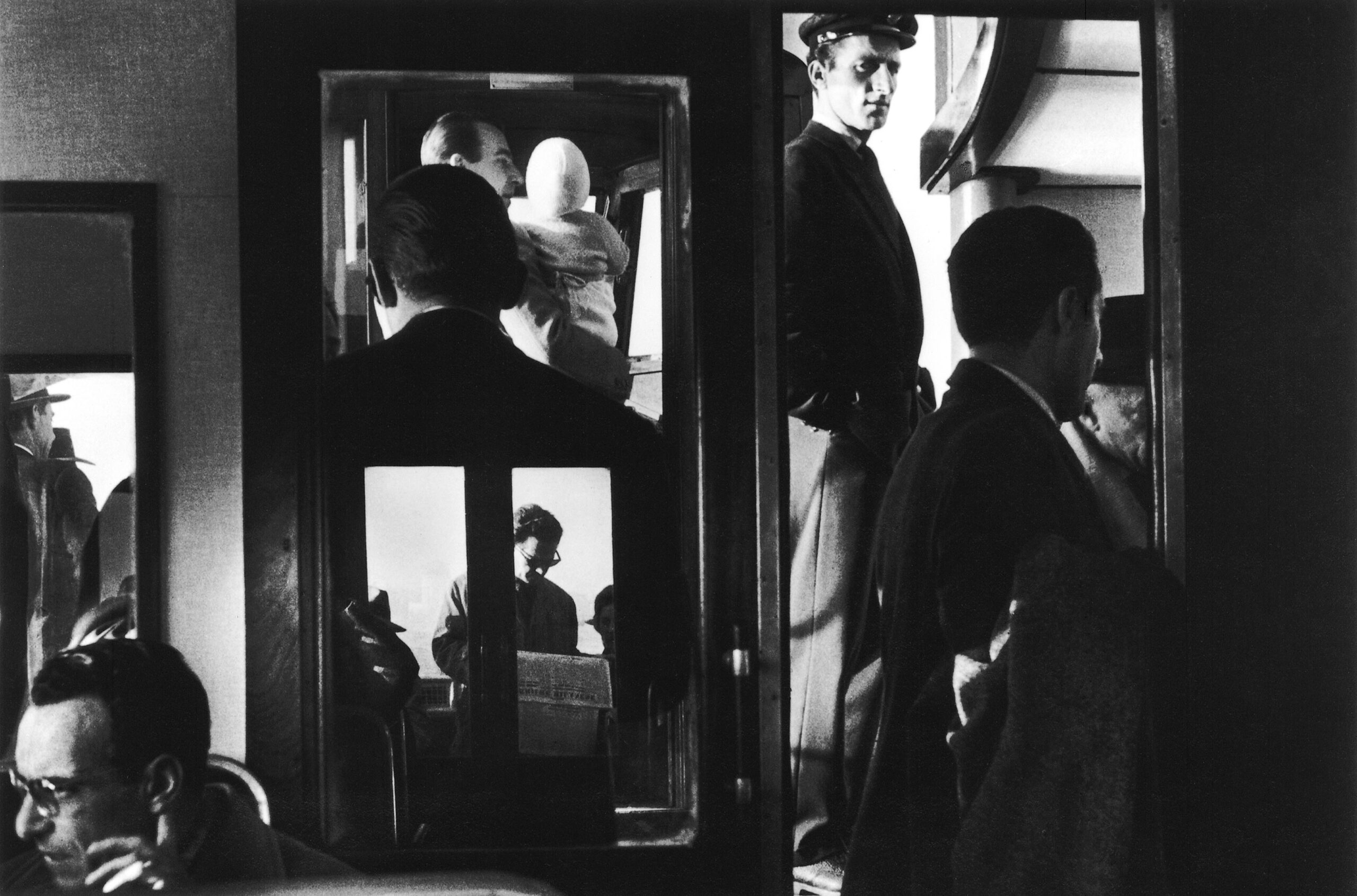

Even though he was born in Santa Margherita Ligure, on the north-west coast of Italy, Berengo Gardin identified himself as a Venetian: ‘My father is Venetian from St Mark’s Square, my wife is Venetian, my children are Venetian. Although I was not born there, I have always considered myself an adopted Venetian’ (Reuters). And it was in Venice in the early 1960s where his photography started to be discovered, with Venice and Venetians the subjects of his first photographs. These ‘Venice years’ resulted in the publication of his first book ‘Venise des Saisons’, but not without having first been rejected by many Italian publishers, who argued that his focus on atypical scenes would not ‘appeal to the tourists’. Ironically, arguably some of the images for which he is best-known were those made in Venice, including the one of which he was most proud and which he believed signalled his transition from amateur to professional: Sul Vaporetto 1960.

© Gianni Berengo Gardin/Contrasto

Berengo Gardin documented workers’ and intellectuals’ struggles and stories that brought to light the humanity found within marginalised communities of gypsies, rural villages, and cities undergoing transformation. Two notable projects focusing on societal issues that had a genuine impact dealt with cruise ships in Venice and the disgraceful treatment in those days of the mentally ill.

Collaborating with the newspaper La Repubblica, his reportage ‘Le Grandi Navi’ documented how giant cruise ships that visited Venice at that time swamped the city and disrupted the fragile ecosystem of the Lagoon. This played a key role in establishing and supporting a citizens’ initiative to raise awareness and denounce the invasion of cruise liners that threatened the precarious social balance of the city.

Venezia, Aprile 2013 – Le Grandi Navi da Crociera Invadono la Città – La MSC Divina Passa Davanti al Centro Storico

© Gianni Berengo Gardin/Contrasto

In another reportage made in the 1970s, Berengo Gardin, working with Carla Cerati, produced a disturbing documentary series published in the book ‘Morire di Classe’, which focused on how psychiatric patients were treated in Italy. This project didn’t focus on the illness, but instead highlighted the treatment and privations of those held in mental institutions, uncovering details of the brutal conditions at that time. It acted as the mouthpiece for the revolution led by others that contributed to subsequent changes.

Renowned primarily as a photojournalist and documentary photographer, his work included travel documentaries that took him beyond Italy’s borders. Travelling widely throughout Europe and further afield on assignments over many years for the Touring Club Italiano, he published his travel photographs in a series of books- he is reputed to have said that books were his preferred medium for presenting his work. And he published over 250 of them. Berengo Gardin also undertook commercial projects, working with prominent companies such as Fiat, Alfa Romeo, and Olivetti, as well as architectural assignments, working with Renzo Piano, though in each case not recording details of the engineering or buildings, but instead focusing always on the workers- the people who are typically ‘not seen’. For him, it was these people who brought the project designs to reality, and that’s what interested him.

All of his photographs were exclusively black and white, captured on film with his beloved Leica, and never digitally manipulated. He never used a digital camera and regarded digital photography as being an artefact that didn’t represent reality, often referring to it as “fake”. He drew a very clear distinction between making a photograph and making an image- the former being film and the latter digital. He held an unwavering view that a photograph is a document that presents what was actually seen at the time the shutter was released, whereas a digital image could be manipulated and is therefore not a faithful record of what was captured at that snapshot in time. Berengo Gardin’s photographs bore the stamp of authenticity: no retouching, no invention, only unfiltered reality. Speaking in an interview published in Black and White Magazine):

“I recognize some advantages to digital, such as immediacy—you can send a photo to the other side of the world seconds after you take it—and the ability to adapt to lighting conditions. But I find digital photography too metallic, cold, precise, whereas I like the grain of film. And then I think that the ability to shoot endlessly and edit the photo on the computer also changes the photographer’s look. One no longer selects, something will come out anyway, and instead the photo has to be first “thought out,” then taken. Meanwhile, the world is flooded with useless photographs, or rather images, devaluing the value of “real photography.” Not to mention that there is no more printing, and it will end up that there will be no more archives to preserve our memory”.

This debate was something he clearly had with others, in one case captured in conversation with his good friend Sebastião Salgado in a film about his life, he questioned why he (Salgado) had moved from film to digital (Gianni Berengo Gardin: My life in a Click).

Perhaps not as universally well-known as others of his contemporaries, he was nonetheless regarded as arguably the most influential of Italian photographers and recognised as such amongst his peers. Quoting from the citation supporting his Lucie Lifetime Achievement Award (2008), regarded as photography’s equivalent of the Oscars, the year after Elliott Erwitt received the same accolade:

“In 1972, Modern Photography magazine placed him among the ‘World’s 32 Top Photographers’. In 1975, Cecil Beaton mentioned him in the book The Magic Image: The Genius of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day. In 1975, Bill Brandt chose him for the ‘Twentieth Century Landscape Photographs’ exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He was the only photographer to be mentioned by E. H. Gombrich in the book The Image and the Eye (Oxford, 1982). Italo Zannier described him as the ‘most eminent photographer of the post-war period’. He is among the eighty photographers that Henri Cartier-Bresson selected for the exhibition ‘Les Choix d’Henri Cartier-Bresson’ ”.

Selected honours:

World Press Award (1963)

Recipient of the Leica Oskar Barnack Award (1995)

The Lucie Lifetime Achievement Award (2008)

Member of the Leica Hall of Fame (2017)

Published over 250 books

Over 360 solo exhibitions

Contrasto Agency archive: personal archive of over 1.5 million negatives managed by Fondazione FORMA per la Fotografia in Milan.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adriano Henney, born in Italy’s Veneto region and later educated in the UK, built a career in science before turning to photography in retirement. Influenced early on by his artistic family, especially an uncle who was a painter, he developed a deep connection to the landscapes and culture of his birthplace. Today, his contemplative photography—ranging from landscapes and seascapes to eclectic subjects—seeks to evoke calmness and emotional connection, inviting viewers to pause and reflect.

Shannon Jones

August 30, 2025 at 02:39

I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, but I’ve been following a treatment plan with the World Rehabilitate Clinic that focuses on real improvement and renewed strength. The first two months involved daily sessions, and now I go three times a week. The difference has been remarkable. Fatigue no longer controls my days, and even when I push myself, I don’t feel weak anymore. After three months, I’m finally living free from MS symptoms.