One of the most wonderful things about photography is the fact that it is both history and investigation. While, at the moment a shutter release is pressed, it’s quite likely the photographer finds the milieu obvious and commonplace, all the image needs is a bit of time for the ephemera of the shot to be seen as a revealing compositional element.

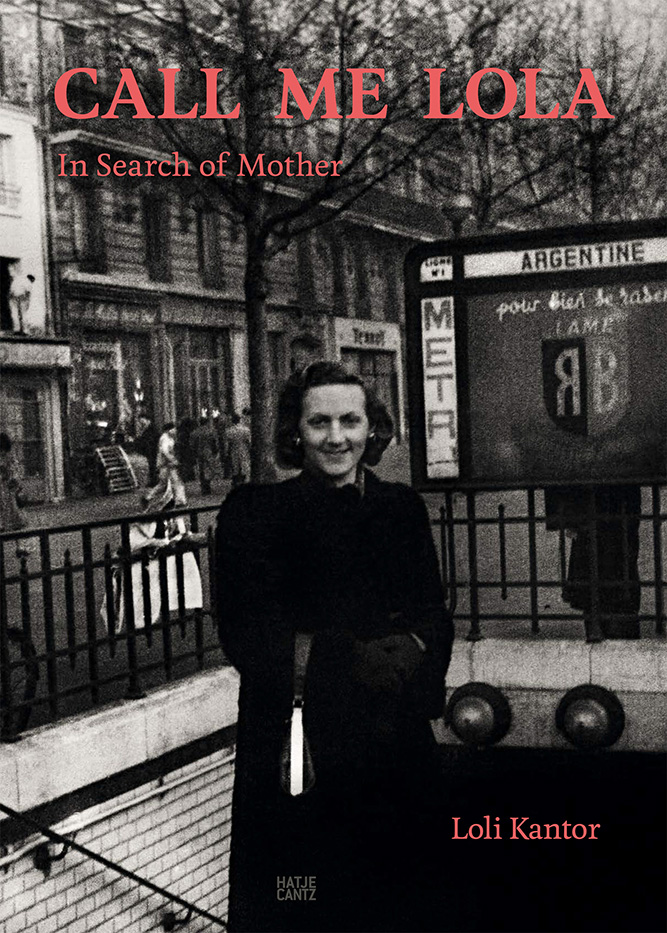

“Call Me Lola: In Search of Mother” by Loli Kantor

Published by Hatje Cantz, 2024

Review by W. Scott Olsen

Give any image a little bit of time and context becomes less present in the minds of viewers. Give an image a lot of time, and it becomes a way for contemporary audiences to investigate the past, to look at a building, a piece of clothing, a situation, and wonder, because it’s no longer obvious, what’s going on here.

Photography is history. Photography is anthropology. And photography is deeply personal in the way we carry out our investigations.

I have on my desk today a gut wrenching and curious book called Call Me Lola: In Search of Mother by Loli Kantor. Kantor’s mother died two hours after she was born. Her father and her brother also died very young in their lives. An early orphan, Kantor is also in possession of two things we find immediately recognizable: a collection of artifacts and a desire to know one’s history.

Kantor is also an artist, with an artist’s sensibility, and the book follows her look at the artifacts to ask essential, important questions. The book begins with an image of a pin in the shape of the letter L, both for Loli and Lola, which is followed by a picture of Loli in her studio surrounded by images. Then an image of a drawer filled with memorabilia. The stage is set.

Call Me Lola: In Search of Mother has one of the best, most erudite and insightful introductions I’ve read in a photo book for a very long time. By Nissan N. Perez and called “Becoming Lola,” it begins—

In general, family ties are strengthened through photographs because “old” images have the capacity to capture the faces of parents, ancestors and past events and preserve, among other things, precious moments of an individual’s life: they tell a story. These representations are inevitably emotional and reinforce a sense of belonging and the continuity of lineage. Such a collection’s narrative and visual chronicle form a legacy that generates bonds across generations and furthers a sense of identity. This is what artist Loli Kantor has been actively investigating in a long term artistic project in search of memories, or rather, of inventing new ones.

A bit later, he continues–

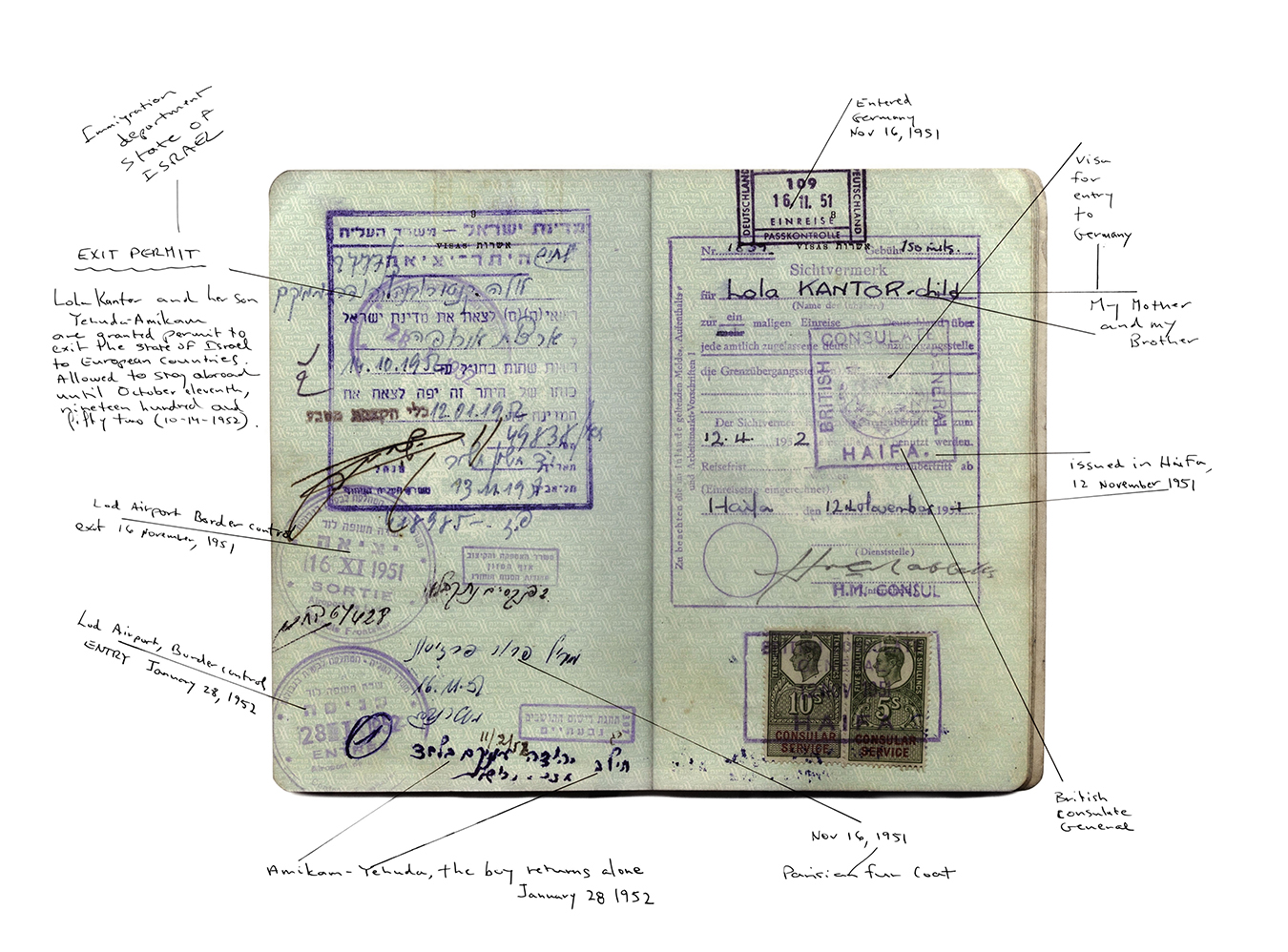

For over a decade, in her ongoing investigative project titled Call Me Lola, Lola Cantor—who often goes by her nickname Loli—has delved into her family archive, which is nothing more than an assembly of souvenir objects, family photographs, documents, and artifacts left by her father. For her, these are a repository of elapsed memories—not necessarily hers—that preserve concrete evidence and information, and thus enable her yo investigate her family history and her place within it.

Perez quotes Jacques Derrida, Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, a bit of Proust, and holds forth about photography’s ability to reveal a past and connect us to it, emotionally as well as more objectively.

To begin this book is to step into an investigation and a quest to recover the missing mother. Even more, Kantor’s mother and father were Holocaust survivors, and the world of their growing up is as much a part of the missing story as the people themselves.

The section of the book dedicated to the plates begins with a Jewish cemetery in Warsaw Poland, pictures and leaves scattered on the ground. This is followed immediately by a self-portrait of Kantor’s feet in Paris, where she grew up, on a sidewalk, similar leaves scattered. There’s both distance and similarity. There is identification, even though decades have passed.

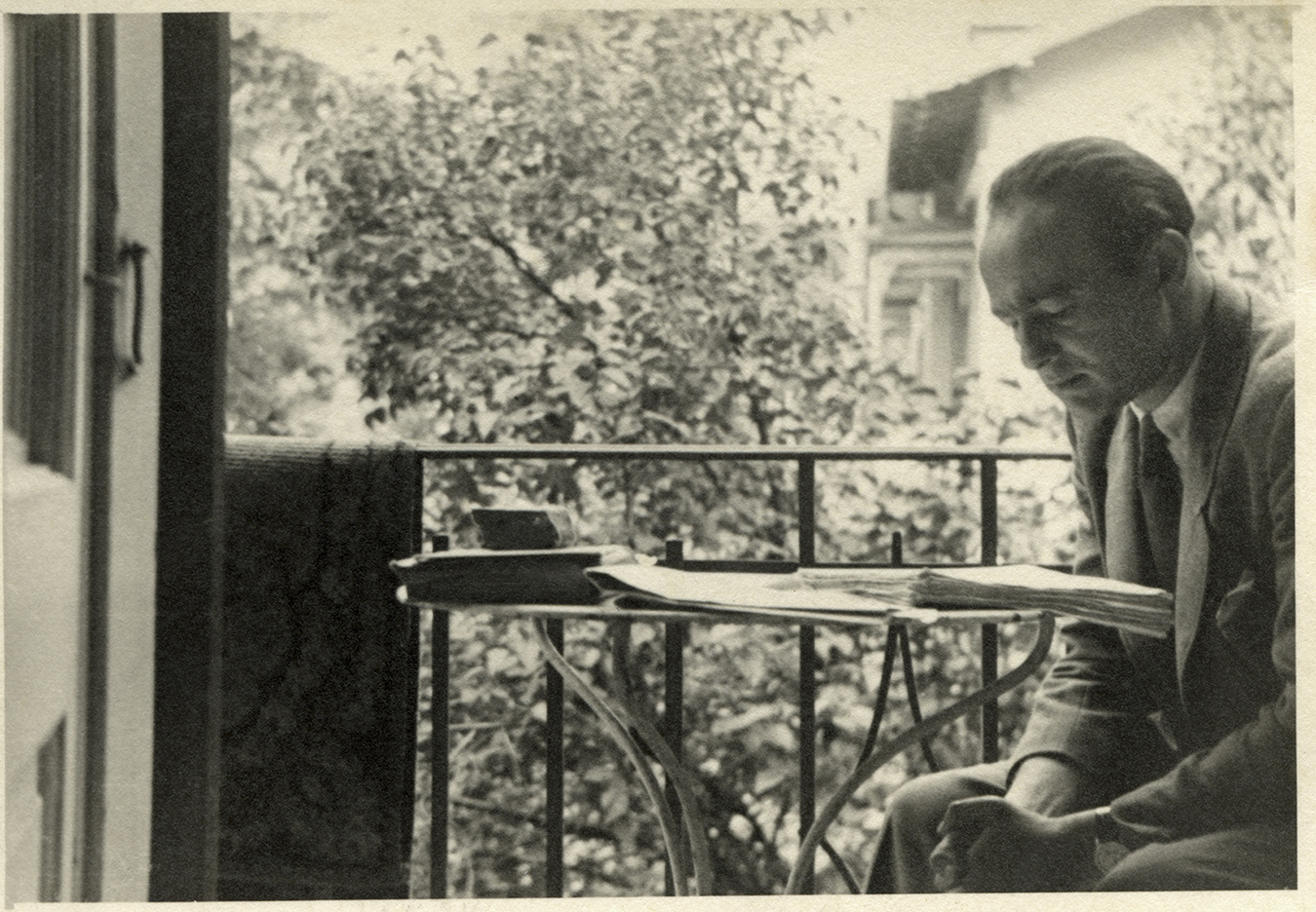

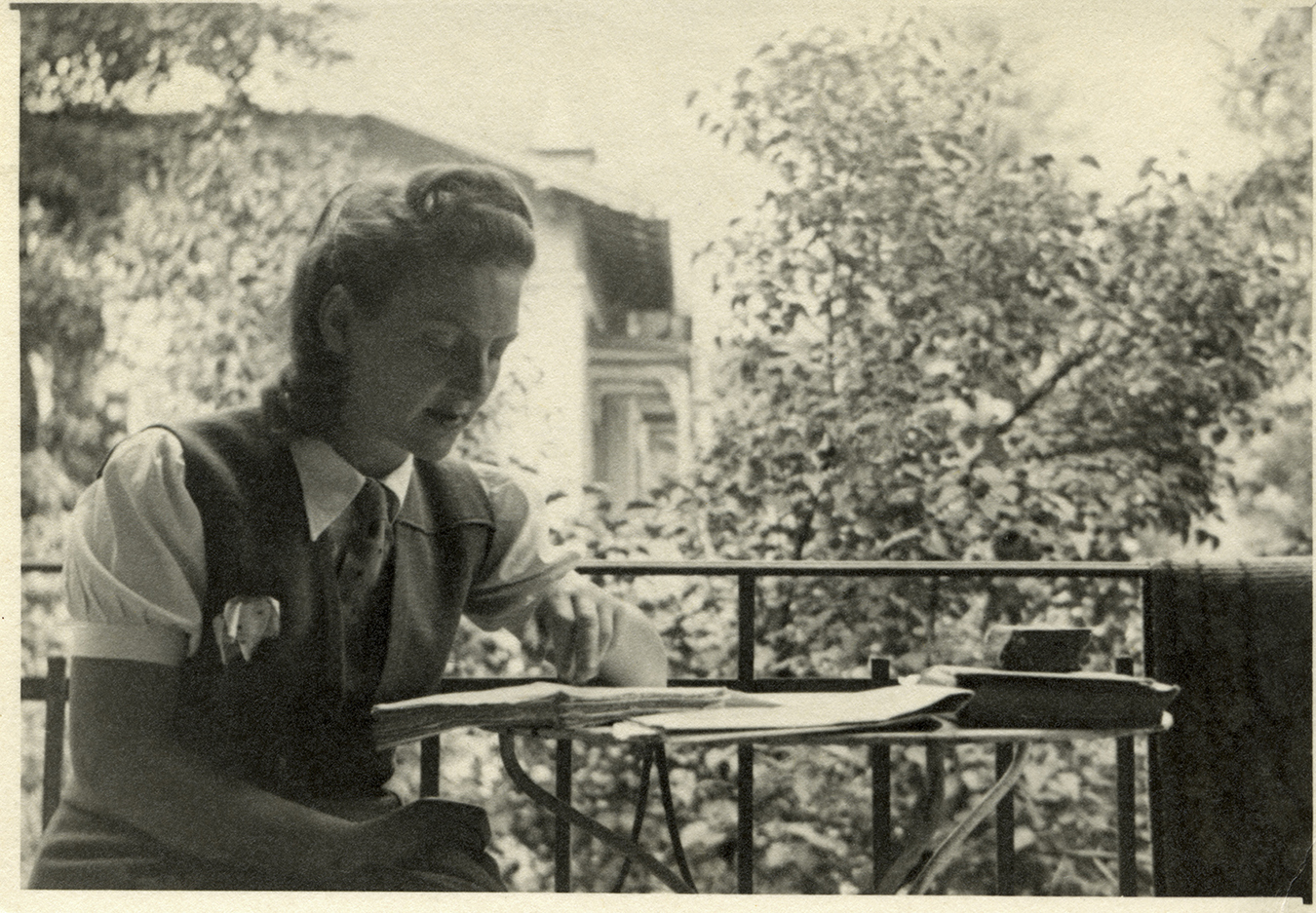

The book reads like a history book, including wedding pictures of Kantor’s parents, a picture of the wedding ring, false identity papers given during World War Two, sepia toned portraits of her mother and father that look like they’ve come out of 1940s Hollywood (they were a dashing couple). The opening pages are a history of the couple, but then, starting with an image of the Eiffel Tower in 2017, the work becomes a revisiting where Kantor visits the places and situations of her memory and history.

Kantor is a wonderful photographer and an engaging artist, and occasionally the images go well beyond documentary work. There is, for example, a double exposure of Kantor and her mother’s grave. Kantor is investigating emotions and loss as much as history, and while the historical images contain documents, snapshots and portraits, the contemporary work is fully in the control of an artist using the capabilities of her medium. The contemporary images blend with the historical images as the book goes on and you realize, finally, it doesn’t matter whether an image is from the 1940s or today. Going through this book, we are invited to participate in the articulation of a search. The search is now.

The images, of course, do not provide any immediate or obvious answer. Images are always evidence of something else, and that something else is elusive and alluring.

At the end of the book, Kantor is interviewed by her own daughter, Danna Heller. Presented in Q and A format as a conversation, the text details how she found photographs of her mother, how she visited sites, how information was discovered and then sometimes corrected.

Heller writes—

You say that each time you look at a photo from this project, you uncover more, and with that discovery there’s perhaps a healing, a sense of closure. By publishing this body of work you are, in a way, rounding off part of your life story. Has that helped you clarify anything in the way you feel toward your mother?

To which Kantor replies—

It deepened my connection to her and sharpened my understanding of who she was. My father and brother continued to enjoy very full lives, and I remember them well. But I feel that my mother was not fully recognized during her lifetime, nor after she died. Between being a mother and an artist, with this work, and the time I’ve spent with the images and documents, I honor her. I’m expressing my love for her, bringing her back to life, and giving her a voice.

Call Me Lola is a poignant book. The images, both past and present, are invitations to wonder about the characters who are emotionally huge in our lives yet exist outside real memory, only as ink on paper, and to use photography as an investigative tool. To study a face, a bit of jewelry, a piece of clothing, so intently and try to get to the heart and soul of someone you’ve never me, and then figure out who they are to you, is both frustrating and necessary. To go along on this journey and imagine ourselves in the same situation is deeply moving.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.

Loli Kantor

April 17, 2025 at 00:16

Thank you for your thoughtful and review, W.Scott Olsen. Thank you FRAMES!