In photography, nothing is off limits.

Except, well, some things are.

It’s all a matter of vulnerability, exploitation, agency and respect.

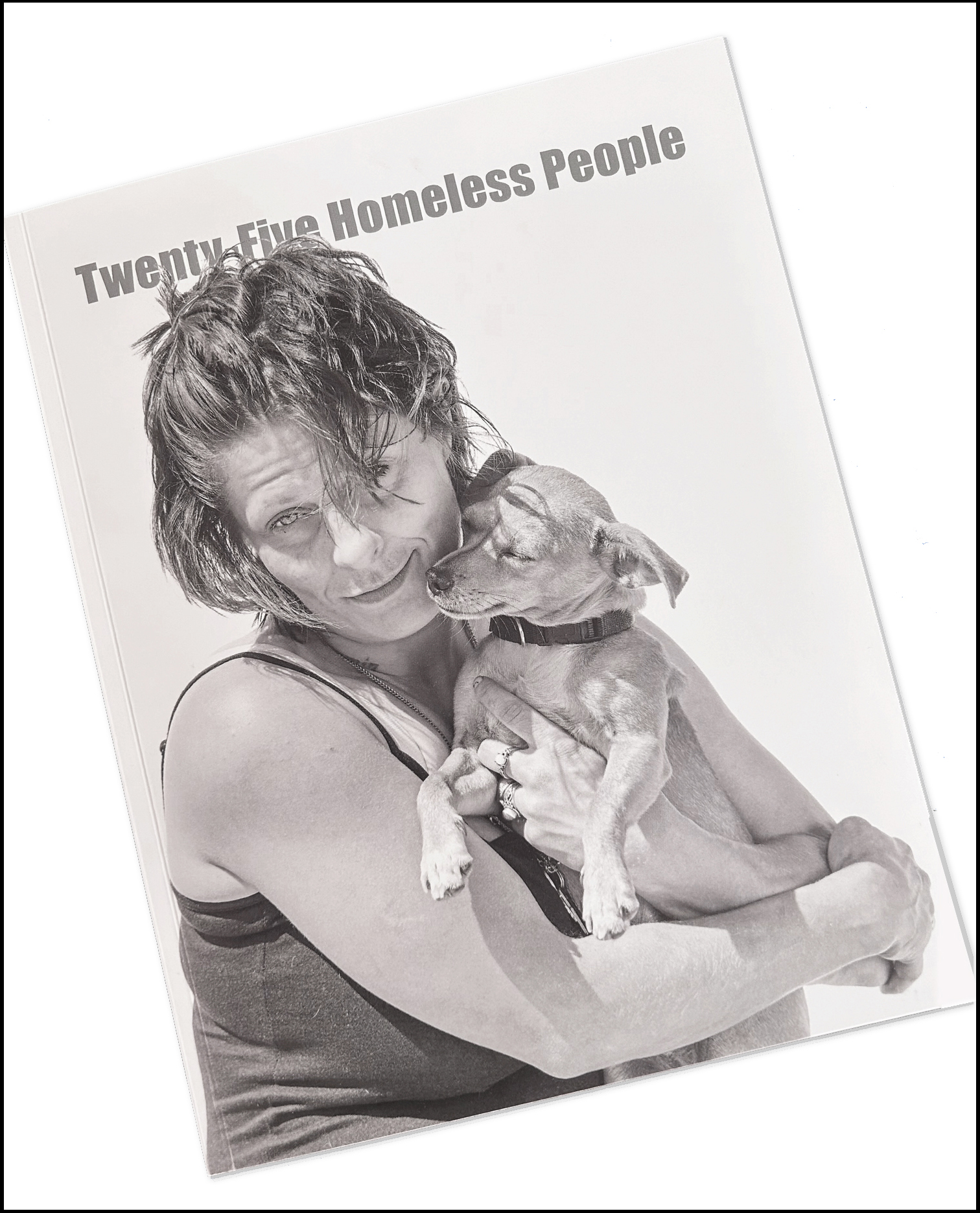

“Twenty-Five Homeless People” by George Phillips

Self-published, 2023

review by W. Scott Olsen

Street photographers know very well that, in most countries, as long as the photographer and/or the subject are standing in a public space, any photograph is legal. In public we are all fair game – our foibles, our beauties, our awkwardnesses, our good and horrific tastes, our good and horrific behaviors. While there are certainly photographers out there – the paparazzi come most easily to mind – who seek to invade someone’s else’s life for fast profit (and yes, I am aware that celebrities often want that kind of exposure, so it’s often a two-way transaction), most often, what catches the photographer’s eye is how often we move through some version of a decisive moment, when light and line and subject combine to create metaphor or tableau or some other access into the deeper currents of humanity. Street photography, at its best, is a genre of candid revelation. And it’s completely legal.

Legal, however, does not always mean ethical.

Images of the homeless, of the mentally or emotionally disabled, of children, of any population that does not have the ability to understand the complexity of the photographic situation and speak for themselves, are generally considered off the table. It’s too easy to fall into the moral traps of explicit or implicit exploitation.

A simple act of respect can change everything, though. Ask permission. Explain what’s going on and what you’re doing. Be honest. Say who is going to see the work, and what you’re after. If you propose an image instead of imposing an image, wonderful doors might open.

Twenty-Five Homeless People, a new book by George Phillips, is a touching, honest, visually and narratively captivating book. It is exactly what the title promises – portraits of twenty-five homeless people. It is also beautiful.

A small image in the back of the book shows Phillips’s setup (see the featured image on top). A solid white backdrop is braced against the back of his car (at least I assume it’s his car). It’s held down with rocks. There are a couple light reflectors, a simple chair or stool, and then a camera and tripod. It’s clear the setup is a photo studio in the field, but also not intimidating or complicated at all. Have a seat, it invites. Tell me a story.

The images and the stories vary. There is the situation of a man who had committed murder. There is the situation of a former tap dancer. There is the story of a man who claims to have worked for Chef Gordon Ramsey. There is the story of a former nurse. Each small narrative, all told in a single paragraph, give keen voice to how a person becomes homeless.

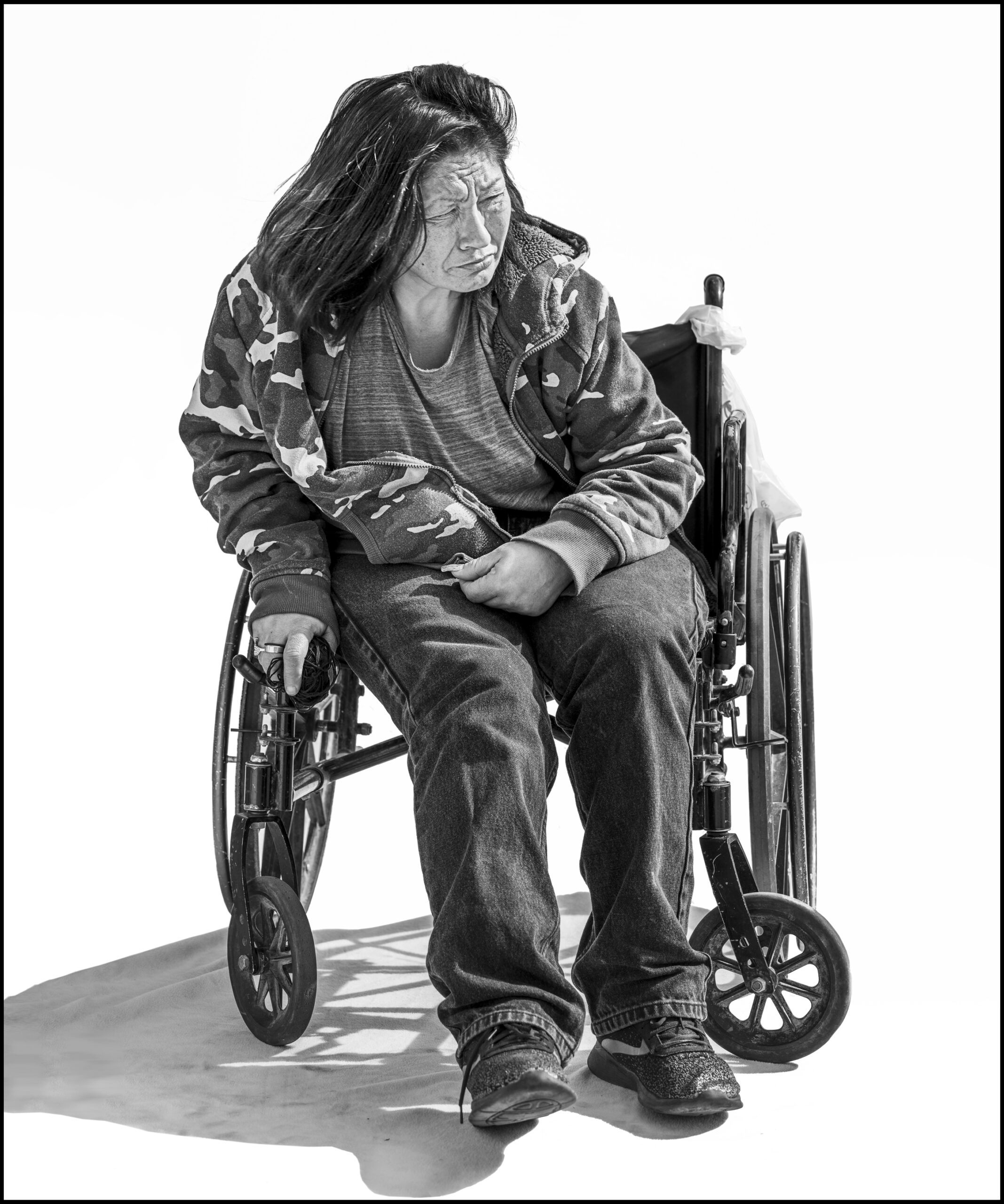

For example, Paul Moore Sr.’s story reads, in part, “I was hit by a car and put in a wheelchair. Ended up losing my job. Much later, I was able to go back to work, but by then I was homeless… I’ve been homeless now for about 3 years. I could go back to work now, but nobody wants to give me a chance… I haven’t given up because I’m still going forward. Am I right? Technically, that’s not giving up. I’m still going forward. As I learned in this relationship, it’s a learning process.”

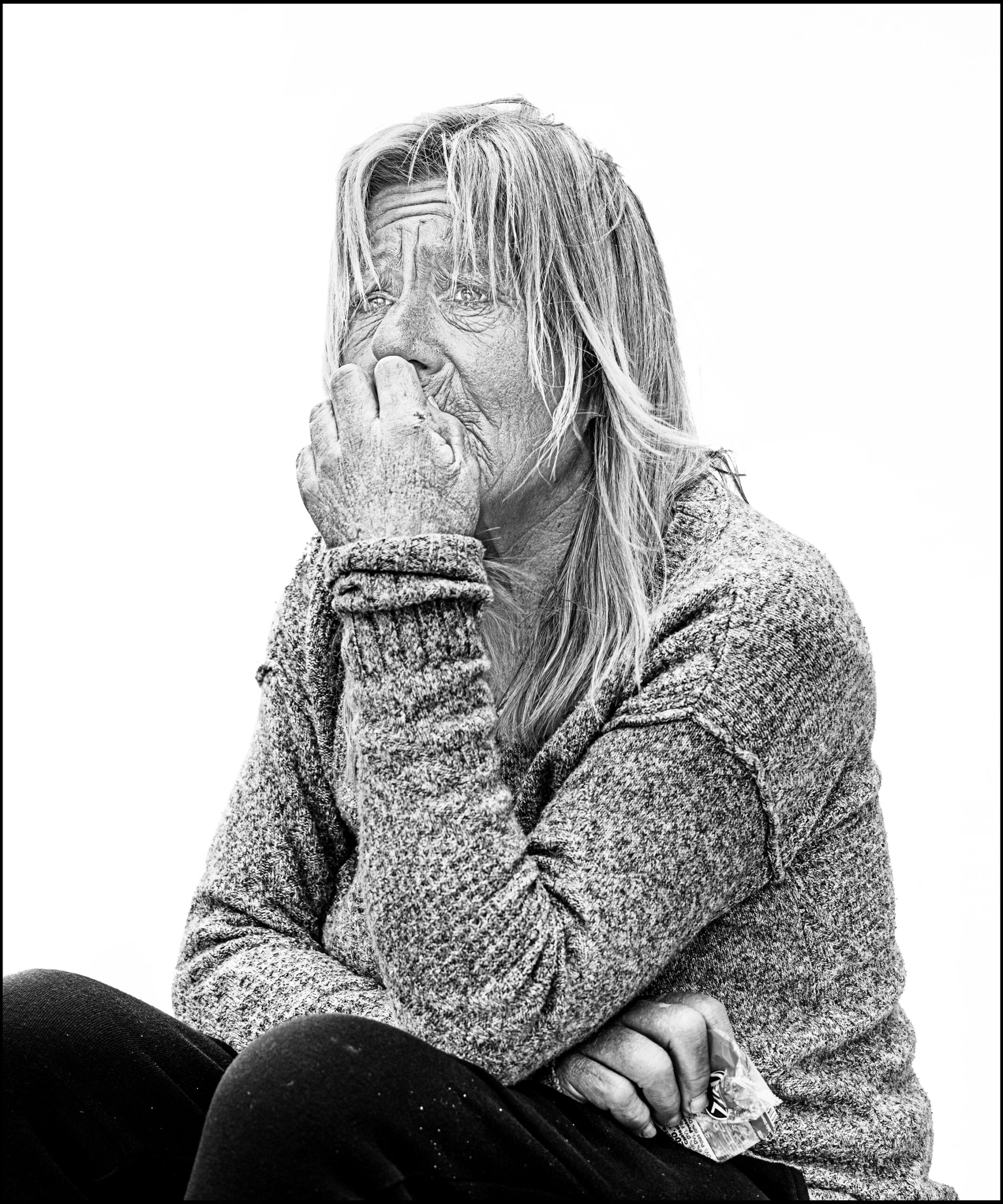

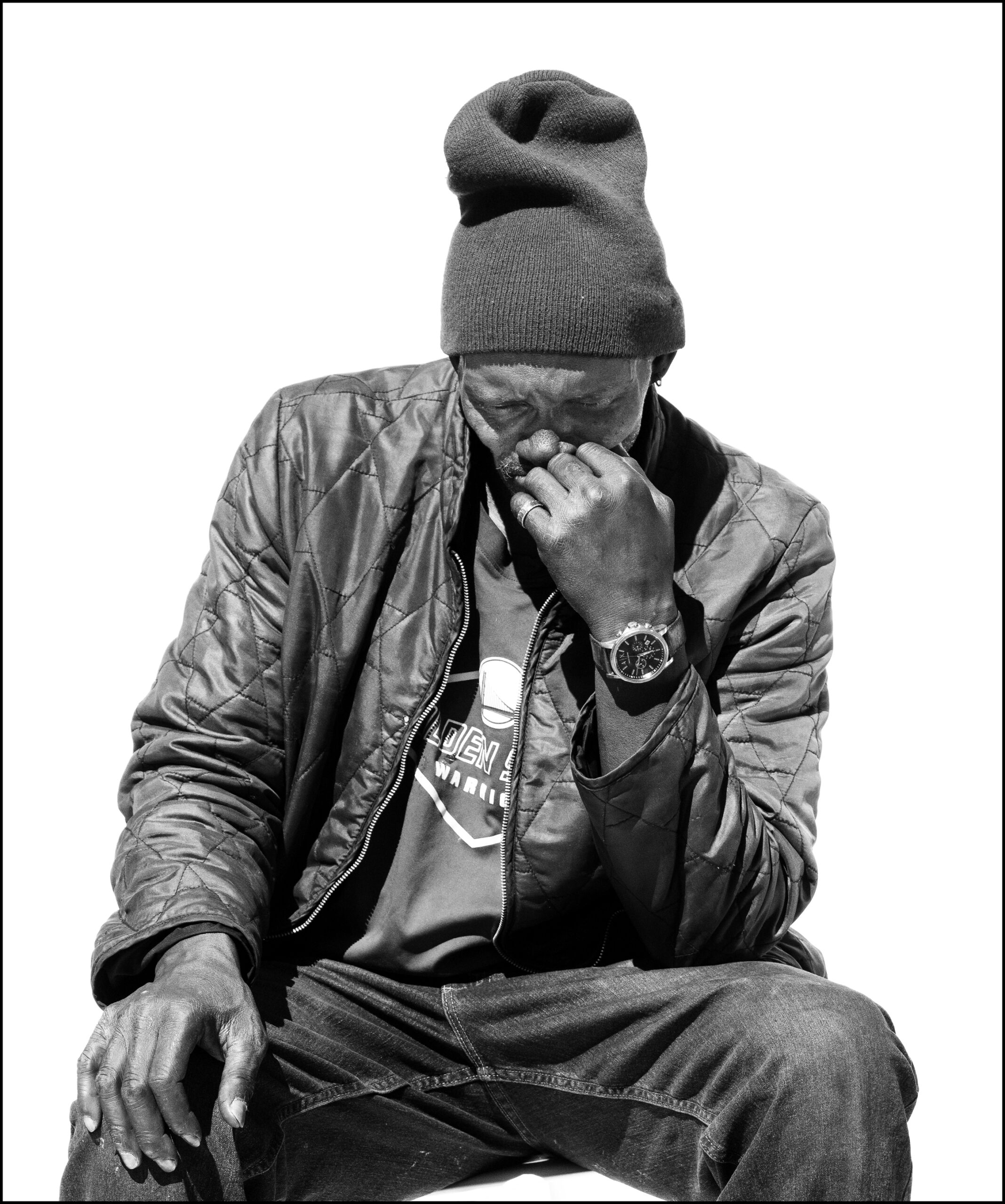

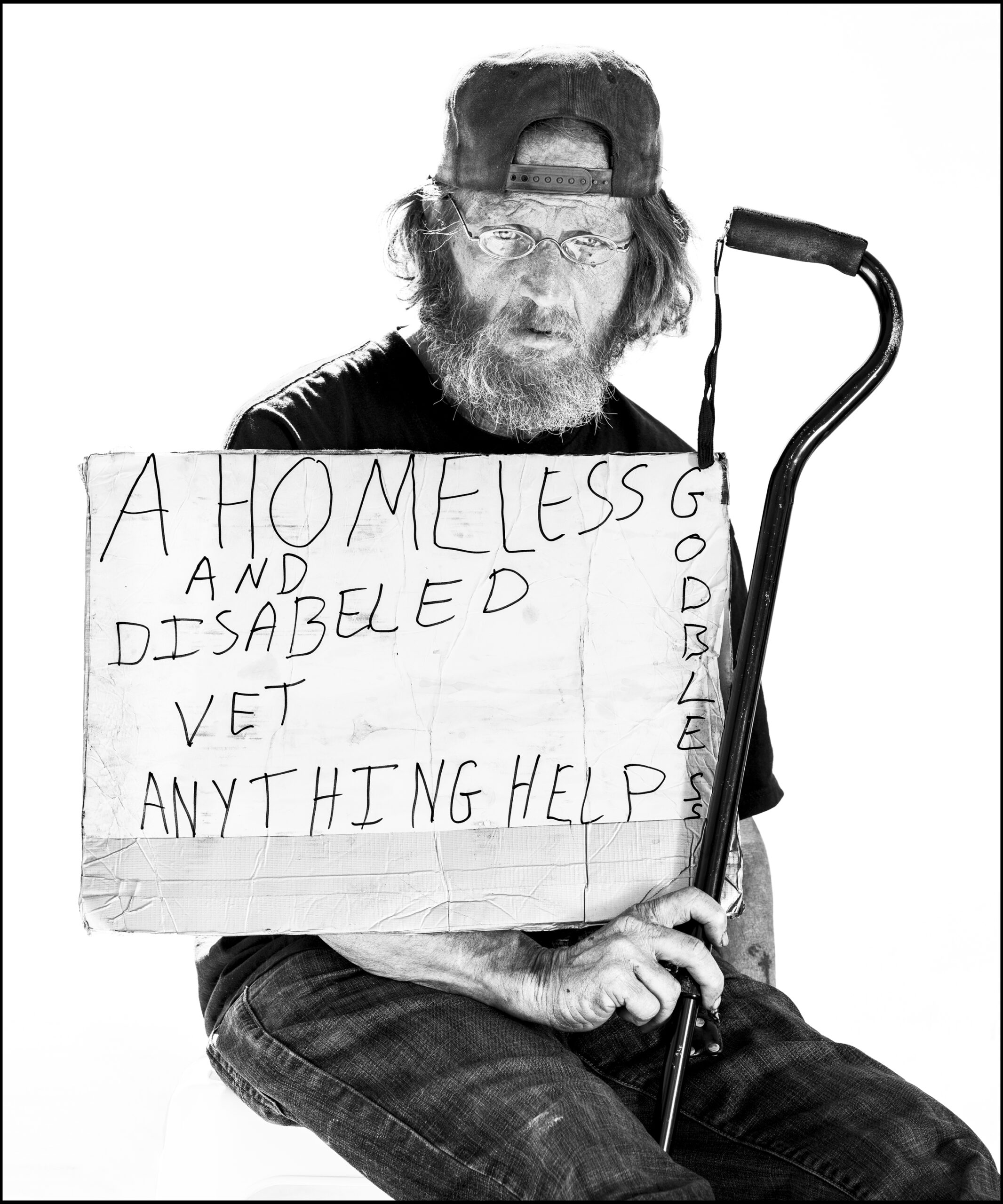

Phillips’s Introduction lays out the idea for this collection. “Often portrayed, and see, as a blight, homeless people can be dirty, drug addled, sick, mentally ill and sometimes dangerous. Glimpsed only occasionally and in passing, amid piles of garbage or on street corners begging, they are seen as a problem, not people. The reality of course isn’t that simple, and homeless people aren’t always who you think they are. I wanted to find out more of the truth… The intimate, clinically sharp, unposed portraits of people on the street isolated against a white backdrop starkly reveal the scars of hunger, abuse, drug addiction, sickness, injury, mental illness, bad choices and plain old bad luck that are branded on the faces, bodes souls.”

The images are all black and white. They are all solo portraits, although a couple include dogs and many include handwritten signs on cardboard, the common declaration of need. Most of the portraits show the person in a moment of contemplation or wisdom. The images convey the dignity carried by the individual.

The images in Twenty-Five Homeless People are also a gallery show, wherein the images are presented larger than life-size. The effect (I have not seen the show in person) must be breath-shaking. In book size, the effect is intimate and almost private. It’s clear these people trust Phillips, and it’s clear he respects them, their histories and stories.

Twenty Five Homeless People is stark. That’s part of the point. It’s honest. It shows the details of an individual. It implies both the aspirations and the tragedies of a challenged life. From a photographer’s point of view, this book is an inspiration. From a citizen’s point of view, this book is necessary.

GEORGE PHILLIPS

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.