In teaching writing as well as speech, an early lesson is “Know your Audience.” If you want your words to create change or convince someone of something, it is oftentimes essential to craft vocabulary toward a specific audience in such a way as to have the greatest impact and clarity. Certain tones, certain approaches, work better with some people than with others.

“Girlhood: Lost and Found” by Jamie Schofield Riva

Published by Daylight Books, 2023

Review by W. Scott Olsen

This is not entirely true of creative writing, however. When somebody writes a novel or a poem or a play, they put it out there for that undefined, mysterious, wonderful, and maddening thing called the general audience. We don’t know who’s going to pick up our work. What we hope, however, is that whatever we have had to say will somehow speak to their heart and mind, no matter who they are.

This is also true for photography. It’s not so much that we are taking pictures for a specific audience, as much as we are taking photographs inside a milieu. We are using a series of compositional elements that speak to a shared experience, but not an experience shared by everyone.

This is not a matter of exclusion. This is, instead, a matter of honesty and intimacy to which not everybody will have the same access.

I’m thinking about this because I have on my desk today a remarkable, poignant, and important book by Jamie Schofield Riva called Girlhood: Lost and Found.

The cover is a pen and ink sketch of a young woman, apparently naked, sitting upright, knees to her chest. It is an image of loneliness and fear. A shaft of light comes from the top left corner of the cover and leads to the bottom right. She is isolated in shadow and light. It is perhaps an image of victimhood as well. Yet there is hope in the subtitle: Lost and Found. So, even before the front cover is opened, there is the promise that this is going to be a deeply personal collection.

Opening the book reveals an introduction by photographer Elinor Carucci, which begins this way—

This debut body of work by artist Jamie Riva is a sheer female gaze, a woman’s perspective, her own. A contemplation of her identity as a woman, a daughter, and a mother, and her take on the male gaze—the gaze that, until not long ago, was the only representation of women in our culture.

This is where I paused. Considering female identity and the male gaze is essential, and complicated, so already, I began to wonder if I would be able to see the deep-core signals, references, and emotional tones in the photographs. As a 66-year-old white male, although my sympathies and politics are firmly with feminism, I do not have the personal experience of growing up female. I began to wonder if, no matter how hard I looked, I would be able to see what this book is really saying.

Reading the Foreword, I learned that Riva was once a model, and through modeling, she came into photography. Carucci continues—

The beauty industry is one of the largest industries in the world, to no small extent because, even today, a woman’s appearance is far more relevant to her value than is a man’s to his.

This much, I thought, is clear. But then she writes—

If we give in to our impulse to allow or even encourage our daughters to make themselves as beautiful as possible, will it be the right thing to do as a mother? Will they forgive us? Will we forgive our own mothers for maybe doing the same to us? Or understand their motivation to do so? Or maybe even thank them?

Riva is herself a wonderful writer too. In her introduction, she begins—

“Girlhood: Lost and Found” is an exploration of the experience young girls face growing up in a world full of preconceived notions of what it means to be a woman. Lost objects in the street coupled with intimate portraits mirror the many ways women lose their sense of identity as they maneuver through life as a female. This work began as a personal journey to discover a way back to the person I was before I learned how the world saw me.

It is an engaging proposition.

Toward the end, she writes—

How do we reclaim the lost girl and her true nature, betrayed by false truths and unrealistic expectations to fit the restrictive mold accepted by society?

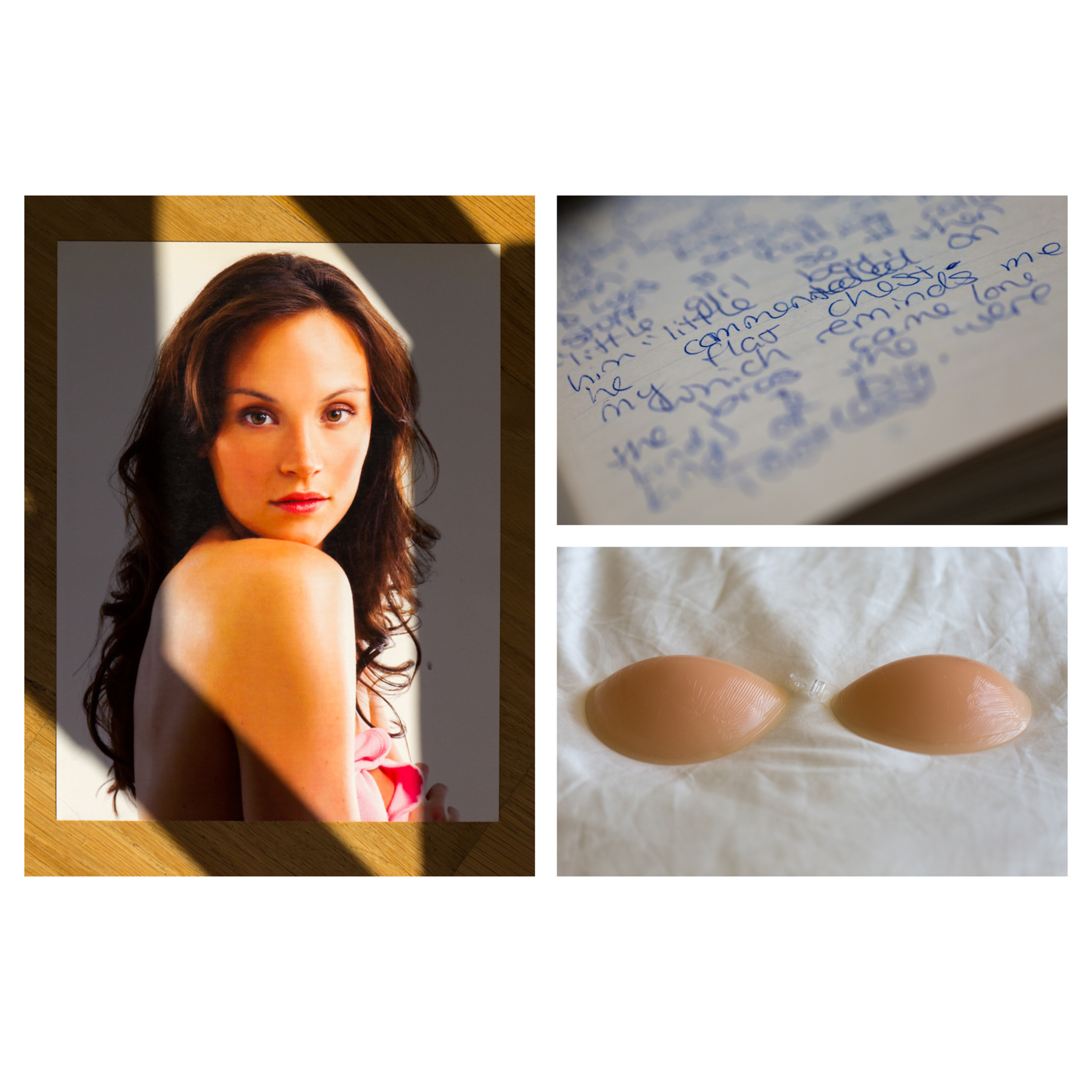

The photographs in this book are a remarkable journey. Some are candids. Some are highly composed studio shots. There are broken and discarded Barbie dolls, young girls in makeup, professional modeling shots. There is the hand of a young girl reaching for a red suede high heel shoe, as well as a nursing mother, feet on a scale, pictures of journal entries about self-beauty, etc.

The book contains a number of small, inset, transparent pages with text, personal testaments by women, each approaching the issue of identity and appearance, that provide commentary as the book goes along. In terms of book arts, they are elegant pauses, their transparent nature both concealing and revealing the image behind them.

There is also a small mini magazine, which falls in your lap the way subscription cards and special offers fall in your lap while paging through a great many women’s magazines, advertising various forms of beauty. The memory is both emotional and physical.

Riva is an insightful and provocative photographer. Going through this book is to enter a contemplation which I’m sure is very different for women than it is for me, and therein lies one of its particular strengths.

Wondering, I shared the book with a colleague named Liz, a 30-year-old woman who has already spent half a decade teaching young women and men in eighth grade, and another three years teaching high school, who is now a professor of English where I teach.

“What I found interesting,” she said, “is the pictures which don’t have human subjects are dark, like the crushed Barbie head, crushed like it was a popsicle on the ground. I don’t mean brightness-dark. I mean sad. In a way, nostalgic. The pictures that do include human subjects are pieces of womanhood that don’t often get talked about. Stuff that just happens, and it’s so normal it isn’t always talked about, like the unshaved legs with high heels. That was interesting to me because that’s normal. There were pictures, like in the closet with all the high heels, or the sign that says, Nothing you do for Children is ever Wasted. Those were interesting to me, because I think those are the messages, among many, society places on women.”

“The book speaks to your experience growing up?” I asked. “Did it seem true?”

“Yes, but it didn’t feel like my childhood. It felt more like my current life experience. I have plucked my gray hair before. I’ve had stray grays pop up out of nowhere, and it freaks me out. While I might say, Okay, there’s a trope. There’s a cliché. If we’re going to talk about women, of course, we’ve got to talk about high heels. But for me and others, it wasn’t the heels. It was everything.”

Wasn’t the heels. It was everything.”

I remember the last thing Liz told me. She was not speaking in the past tense.

“The book resonates with me, and that’s all because I live it.”

Girlhood: Lost and Found does not have the resonance for me it will have for women, but that is not to say it does not have resonance. Women may pick up this book and say: Yes, exactly. Men may pick up this book and feel something important and true.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.

diana nicholette jeon

April 24, 2025 at 12:27

It is my opinion that you are correct, as a “66 year old white male”, cannot know the experience of a women, any more than I as a women can know yours. Our images give hints of our experiences, but I don’t believe that you can look at a book made by a woman about the life experiences of women and see the same thing that I as a woman would see.

I did a podcast with Scott (about to come out) and in it he specifically asked about one feature of The Female Gaze where I wrote about women in street photography, and he delved into a statement I made about women and men are not taking the same picture when they make street images. I didn’t have language (it was on the fly, I had no knowledge the question was coming; if I did I would have been better able to address it, I believe..) but it was clear that we were talking apples and oranges to each other in trying to describe the sameness/difference factors. In retrospect, I think the most cogent statement I can make about this disparity goes back to https://readframes.com/the-female-gaze-girlgaze-no-6-on-the-unique-vision-of-female-photographers-women-on-the-streets-by-diana-nicholette-jeon/ that same article, and this discussion of Gina Costa’s image there:

quote:

I was utterly captivated by this image by Gina Costa when I saw it years ago. Had I not known via our connection through FB photo communities that it was a street photo, I would have never guessed. It looks like an intentional portraiture work. The image is elegant, soft, and beautiful. In this photo, I declare that the result is much different than an image of the same woman on the street would look if taken by a man. I can feel Costa’s empathy for the broken woman (yes, woman, not shoe) in the lyrical quality of the image. Perhaps unsurprisingly, if we believe similarly to the Loftis quote I referenced earlier, Costa told me, “As soon as this photograph was first exhibited, the response to it was immediate and passionate. But what was remarkable to me was that the response was 100% gendered. The male response was how sad this beautiful woman broke the strap of her shoe. The female response was not about the shoe but rather the underlying broken state of the woman. They viewed her as a symbol of so many seemingly well-situated, comfortable, and privileged middle-class women who pay a heavy price for domestic comfort that only other women see and truly know.”

When we see, we can only see through what we have experienced. I view your willingness to try and understand as super cool and commendable. Especially when we women in America are having our rights threatened. Thanks for the commentary on Riva’s book.