There is a problem which haunts every photographer, no matter what type of photography, no matter what genre, no matter what level of experience or expertise.

Sometimes it’s called The Imposter Syndrome.

Eric McCollum – “Always Rejoice”

Self-published, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

So many other people have done such fantastic work, we think, everywhere on the planet. We stand wherever we may be standing, camera and lens in hand, and wonder: What in God’s name am I doing here? What do I have to offer?

These are deep questions, personal questions, which revolve around every subject. Is there a difference, for example, between an extraordinary photograph and an ordinary photograph of something extraordinary? Is the power of the image in the subject or my way of capturing it? The answer, of course, is both. But the questions remain.

In the literary arts, we often talk about narrative voice and style. We don’t talk about that as much in photography, at least not with those words, but this is an issue that consumes all of us. What do I have to say in a way that only I can say it? Think Leiter, Meyerowitz, Arbus, Penman, Smith.

I’m thinking about issues of voice and style and authenticity, because I have in my hands today a book called Always Rejoice, by Eric McCollum. Always Rejoice, I will say right up front, is a special and wonderful book.

In the very brief introduction, McCollum writes:

As a photographer, the West intimidated me when I first moved here. Everywhere I looked was a grand landscape. I often raised my camera to my eye as I drove or hiked through the mountains and high plains, only to lower it without releasing the shutter. What could I add to the legion of existing photographs that tell us of the grandeur of the West, the challenge, the uncomplicated beauty? It wasn’t until I began photographing with a Holga camera that I found a new vision.

Oh my, I thought. Think Michael Kenna.

I should add right now a bit of full disclosure. A year or so ago, when I discovered I could buy a Holga lens to fit on my Nikon camera, I didn’t hesitate to make the purchase. The Holga lens is, by all measures of lens quality, a horrible lens. Likewise, the Holga camera is a horrible camera. Bad focus, light leaks, the system boasts a million technical things that are simply insufficient, but that’s the point. The Holga camera and the Holga lens have character, voice, and personality. There is a reason Holga has become a favorite. They see the world differently than lenses that advertise their ability to be tack sharp to every corner.

To be clear, a Holga camera or lens will not create great photography. However, the Holga is a way of seeing, and it influences every bit of subject choice and composition as well as post-production.

What McCollum did was go back out into the West with a camera to photograph the place, but also the mood, feeling, and sentiment. McCollum’s use of the Holga camera adds an air of obfuscation and mystery, and the result is a book I find deeply satisfying and compelling.

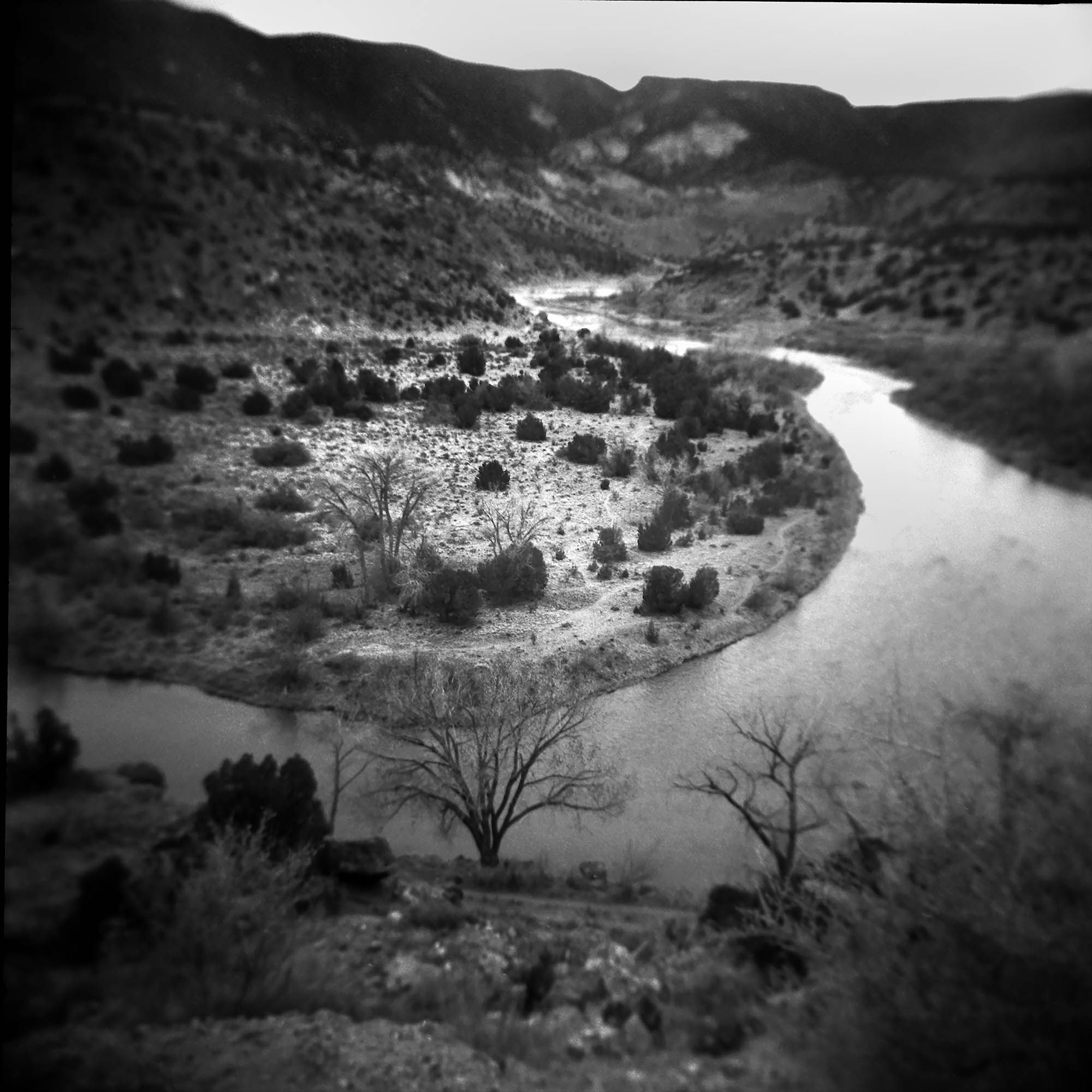

An image of the Chama River in New Mexico almost looks like it’s taken with a tilt shift lens, a bright center falling off into darkness and blur at the edges. An oxbow in the stream, some scrub, vignetting. The image is mysterious and inviting. Much more psychology than ecology, although ecology is certainly present too.

With different images, a tree in front of an adobe wall in Santa Fe is more implied than represented, and so I linger. There is graffiti on a billboard frame that says God is Real, with a happy face and a heart, and I wonder. There are some cacti in mist, a row of bottles on shelves in Los Cerrillos, and an incongruous Buddha in South San Ysidro. The images are noise-filled, soft-focused, and yet they are all also brilliantly composed. McCollum knows his subjects’ shapes and tonalities. Something as simple as a black bird in a niche in New Mexico, a square image, is a masterpiece in light and shadow and gray tones, all interpreted freshly via the Holga.

All of the images in this book are black and white. And all of them seem old, even though they are not. That’s one of the characteristics of the Holga. It seems to find something ancient, even in the most contemporary situations.

Always Rejoice is a short book, only 62 pages, and its title is not an accident. Because “rejoice” is both a common word and an uncommon title, I looked it up. To rejoice is to feel great joy or delight. As a verb, it means to cause joy. In Biblical terms, it is a call to joy and is often used as a salutation.

The phrase is also graffiti painted on the side of what looks to be a large water tank set among some scrub along what may be a dirt path: “Amen. Always Rejoice. Be happy. Heaven. Glory.” The message, the tank, and the setting are all incongruous. The blur of the Holga causes a deeper viewer engagement.

Like most people, I have seen 1000 color, brilliant, sweeping, precise, panoramic photographs of the West. And I have seen the black and white work of Ansel Adams and all his heirs. Landscape photography in the American West enjoys a fine and profound history. But what do you do when you are not the first one at the party? In the case of Eric McCollum, you take a step not away from precision, but to a different type of focus.

The result is a soft focus to the image. A laser focus to the heart.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.