One of the powers of photography is its ability to isolate.

By definition, a photograph is an isolated moment. We isolate time. It doesn’t matter if the exposure is MIT’s one-trillionth-per-second camera that can catch the speed of light, or the eight years of Regina Valkenborgh’s Bayfordbury Observatory’s solargraph; every exposure has a beginning and an end, which separates it from the rest of the temporal universe.

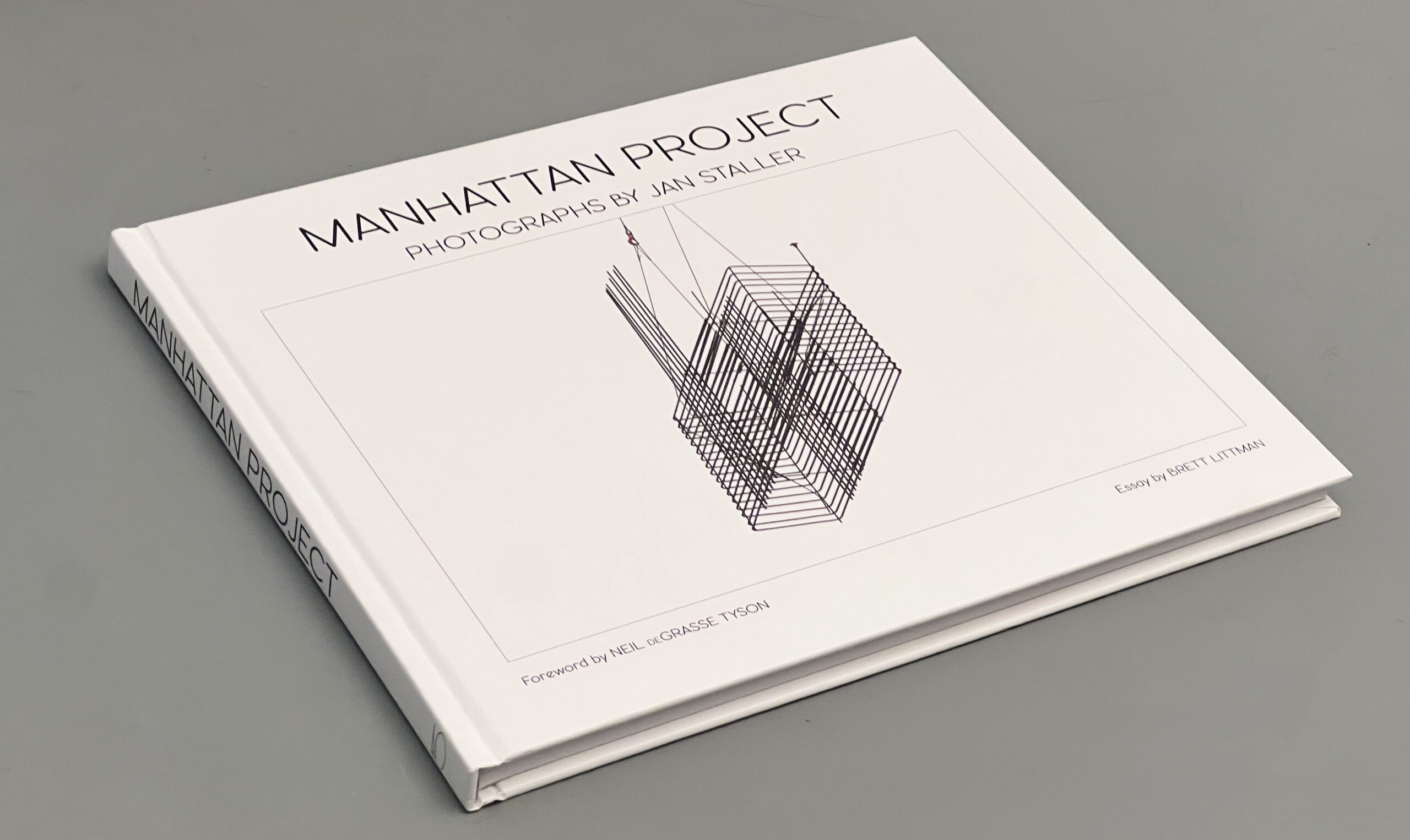

Jan Staller – “Manhattan Project”

Published by 5 Continents Editions, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

Equally important, photography has the ability to isolate a subject. We isolate space. The simple act of composition, of framing, limits what will be included and calls our attention to something in particular, even with a very wide-angle lens.

We often talk about how a fast lens can separate a subject from its background. There are post-production tricks, such as changing the exposure level of a background, to more fully isolate a subject, too. Isolation is just another word for calling our attention in a particular direction.

When we compose a photograph, we look at the elements within the frame and their relationship to each other. One of the reasons minimalism is so popular and so moving is the foregrounding of the value of isolation. Of course, I don’t mean isolation in the psychological or social sense. I’m not talking about loneliness. I’m not talking about disconnectedness. What I’m talking about is actually an act of love. To focus on something, to pay complete attention to that something, can be, and one might argue should be, an act of admiration, of respect, of appreciation for dignity and value.

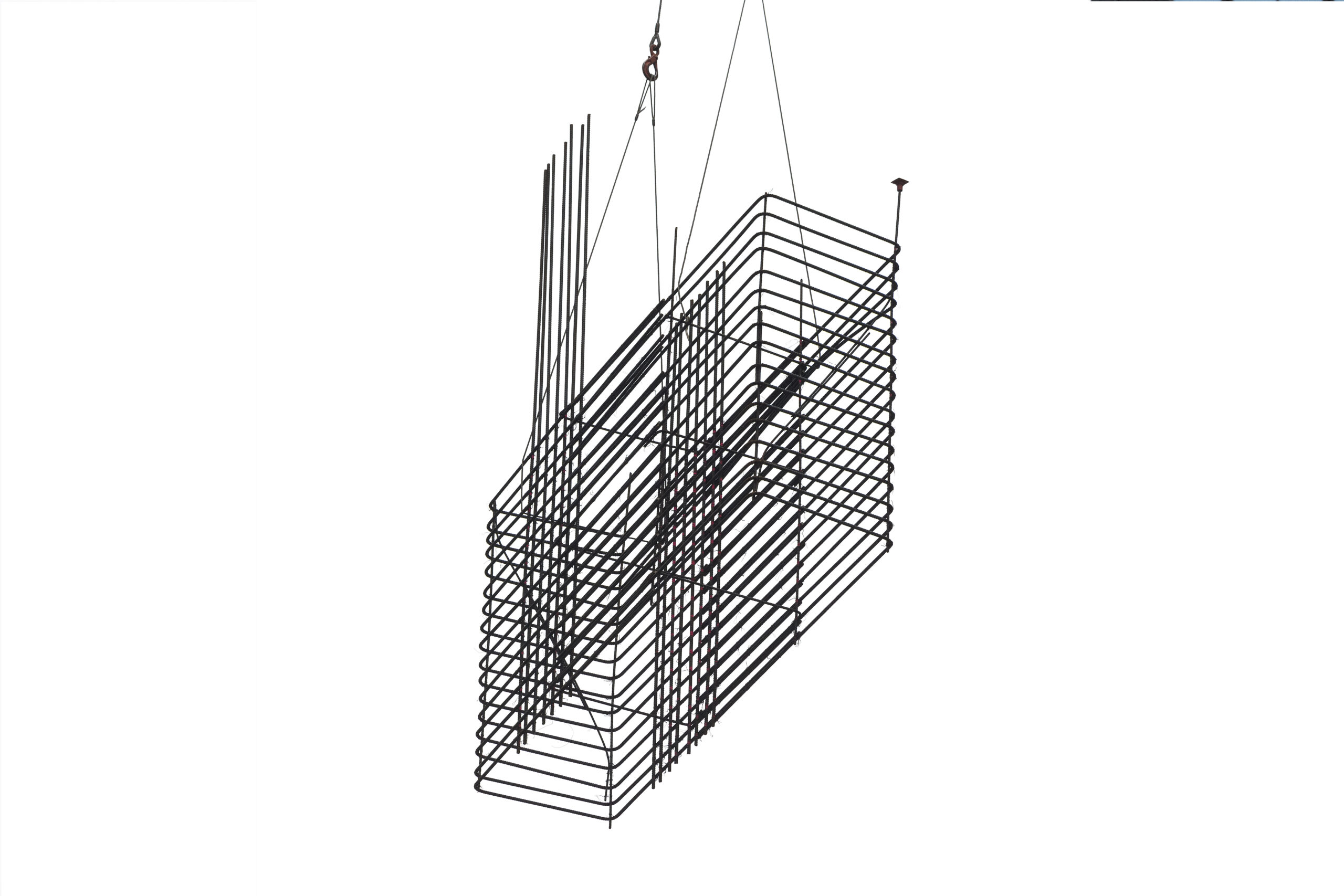

To wit, there is a new book called Manhattan Project, by Jan Stoller. The cover shows a rectangular arrangement of construction rebar suspended by wires. The cover design is simple, clear, and well-defined, and the image, at first glance, appears black and white. But if you pay just a little more attention, shades of orange come through. Like so much of this book, the cover rewards closer attention.

Looking at the cover, you see there’s a foreword by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and an essay by museum director Brett Litman, so if you’re like me, it’s no surprise that somebody’s first reaction might be: “Oh, this is a book of photographs of the building of the structures that produced the atomic bomb.”

That is, however, not the case. Manhattan Project is a book about construction in New York City, in the borough of Manhattan. But even that description is wrong. While the images were all taken at construction sites, this is not street photography in the way we would normally think about it. There’s no steam, no pedestrians with odd looks on their faces, no poignant moments between people as they move through their day.

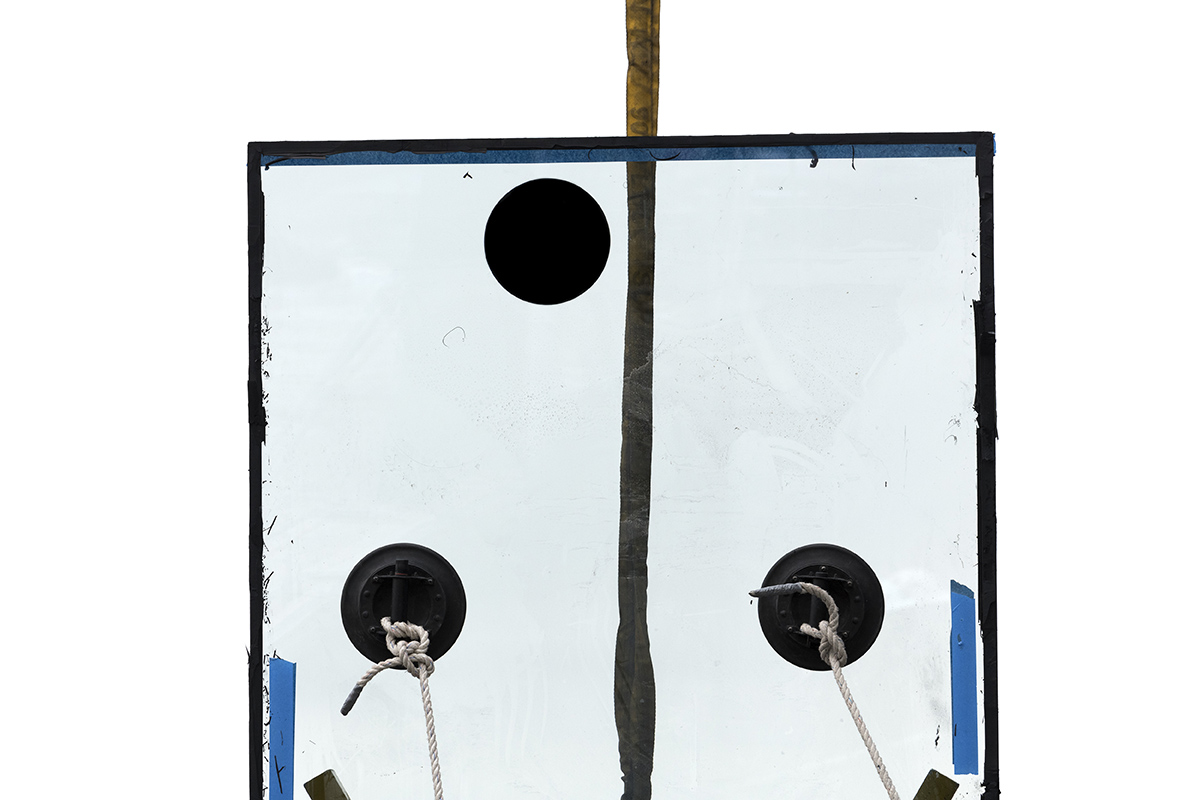

Manhattan Project is 100% about building. And not the process of building, or building design. This is a book that isolates and thus celebrates the individual parts that go into construction, the things we build with. Rebar, for example. And pipes, hooks, suction cups that hold glass windows, and augers. The genius of this book is that this is a kind of street photography that is also minimalism, that is also portraiture.

In all of these images, Staller has taken his subject and not only reduced the background, but also eliminated it. The elements are isolated from everything else, set against a white background, evenly lit, so we get to pay attention to shape and texture on its own. For example, there is a lot of rebar in the opening of this book, most of it in the process of being lifted somewhere. We see the wires and the hooks. We don’t see any sense of place. What we get is geometry and shape, angles and volume. We get to see the patterns, not as they are about to be used, but as they are themselves. And what they are themselves is both geometrically compelling and beautiful.

As the book goes on, we get steel plates (again suspended), pieces of wood, green rebar with tags attached, all sorts of pipes, nuts and bolts of gargantuan size, an electromagnet with some detritus attached. The complicated geometries are each an invitation to pause and consider this thing in isolation, by itself, of itself. Static? Yes. But in the best way.

This is not to say there aren’t moments of real energy and life beyond shape and form. A few of the pieces have chalk writing on them from construction workers. Dirt falls off an auger in one picture, off a shovel in another, then later just into a pile. In one image, a human hand rises from the bottom to steady some rebar. There is, if you look closely, a narrative in every image.

There is something deeply pleasing about shape, and the implications of its future use, and this book celebrates that fact.

In his introduction, Neil deGrasse Tyson writes—

In the Manhattan Project, which is itself a kind of x-ray view of what buildings are made of, urban photographer Jan Staller isolates, identifies, and photographs fundamental elements of the construction worker’s craft. These elements ascend to a form of geometric art, imbued with life, where you can’t help think of I-beams and rebar as the bones and cartilage of the City, where concrete slabs and sheets of metal and glass are a kind of epidermis, and where hooks, pulleys, and diggers are the tools of a mighty force, rendered visible by an artist-photographer who sees what we don’t see, as he reimagines the landscape—the cityscape—that so many of us call home.

The book also contains an introductory essay by Brett Litman, which is an eloquent overview and unpacking of Staller’s work, both historic and contextual. He writes—

What interests me about these works are their ability to foreground tactility, abstract shapes, the weightlessness of heavy objects, the palimpsest of scratches and marks on the objects in the way they aestheticize the juxtapositions of unmonumental materials like plastic mesh, oxidized steel plates, and bundles of rebar. They are also a simulacrum and index of contemporary sculpture. By that, I mean that Staller’s choice of objects and cropping seem to directly reference the shift of contemporary sculptures from Minimalism to Land Art, to assemblages to the readymade.

Manhattan Project is, at one level, about the building of Manhattan. It is particular that way. Although not evident in any image, it’s easy to imagine these parts being put into place, to become part of the visible world we see as we meander through the village or Midtown or Harlem. It is a gritty and beautiful book at the same time.

The pleasure and insight here is that it refocuses our attention and makes the world we move through larger and more complicated, more detailed, and full of identity, which is a joy.

According to the book’s press materials, Staller’s photographs are held in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, SFMOMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, and numerous other institutions. He has received awards from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Hasselblad Corporation. His previous monographs include Frontier New York (Hudson Hills Press, 1989) and On Planet Earth (Aperture, 1997).

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.