According to the infallible World Wide Web, the record for the longest exposure photograph is a bit more than eight years, 2,953 arcs of the sun, taken with a pinhole camera by Regina Valkenborgh in England, starting in 2012. The image, in cool blue tones, has whiteish arcs over what appears to be a gap in a tree line and is captivating once you know what it is.

Robert Charles Mann – “Solargraphs”

Hemeria, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

Long exposure pinhole camera work is a special reimagining of what we do. Normally, we think of exposure times in terms of fractions of seconds. Camera manufacturers boast about and advertise their ability to slice time into smaller and smaller fractions. 1/4000 of a second is good. 1/8000 of a second is better. At MIT there is something called a streak camera which captures one trillionth of a second—fast enough to catch the motion of light itself. Our lives are fleeting, and to hold a small moment of it suspended forever is one source of insight and pleasure.

On the long end, 30 seconds is pretty average for what a commercial camera can do before it changes to blub mode. But 900 seconds, and longer, is out there too. Beyond that, however, we start to move into a different way of seeing. Instead of holding a fraction of time, we are asked to consider something larger, something more gestalt, something huge. Very long exposure photography asks us to consider, perhaps, the shape and colors of time itself. And when the process is intentional, worked in the hands of an artist, the results can be profound.

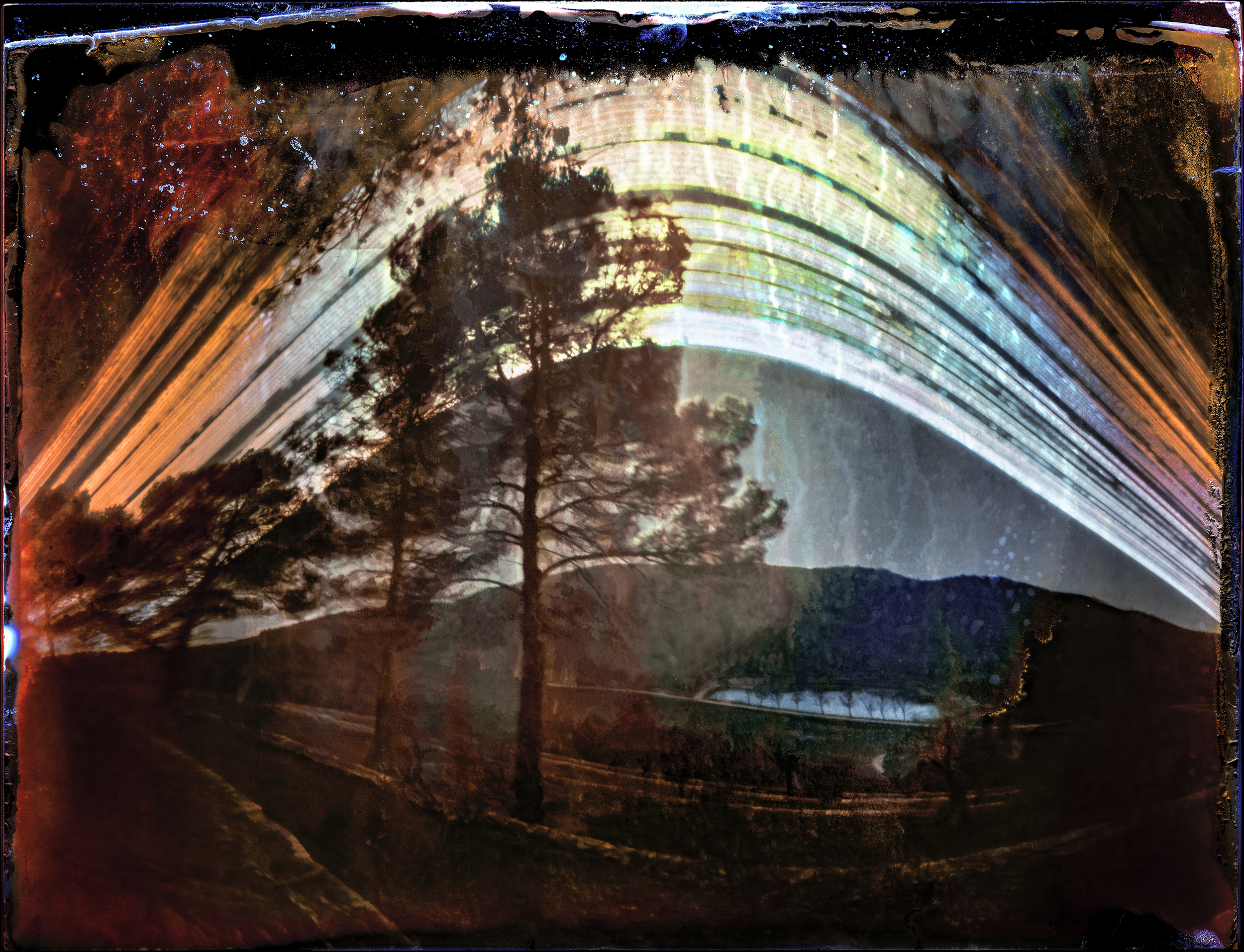

Solargraphs, by Robert Charles Mann, is a collection of fifty images, each taken with a pinhole camera Mann built himself, each exposed for six months at a chateau in the south of France. The book is extraordinary, unexpected, an invitation to a deeper sense of connection with the idea and gut-felt feeling of time.

Through a serendipitous line of who knows who, based on Mann’s work as a master printer, Mann wound up connected with the actor Brad Pitt. Mann did some work helping Pitt organize and print a decade’s worth of Pitt’s photographs, and in the course of their conversations over the years, Pitt’s involvement with Chateau Miraval became important. The idea was born that Mann would install pinhole cameras at Miraval, leave them open for some time, to see what happens.

In a brief introduction, Pitt writes—

And so, every solstice, Robert comes to Miraval to pick up his pinhole cameras and install new ones. The solargraphs he produces continue to amaze me year after year. Each time, I am stunned to see in one image a place so rich in history and the luminous trace of our journey around the sun.

In a separate introduction, called “An art of non-action, or the deposition of time,” journalist Mikaël Faujour writes–

It would certainly be easy to classify these works within the artistic tradition of landscape photography, but such a label would hardly do justice to their uniqueness. They evoke a sense of dreamlike abstraction, of detachment or of the world dissolving, particularly in some of his more recent works that go beyond a mere technical capture of what is visible. Solargraphs can be interpreted in a number of ways, provided one takes the time to explore them, to let them resonate, swaying between pure esthetic delight and a more metaphorical or meditative reaction…

By erasing human agitation and etching a supra-human time, imperceptible to the eye due to its long duration, the solargraphs evoke a metaphor of meditation as the dissolution of time (the haunting past, the anxious future) and as an experience of openness to something beyond us all. Against the illusion of technological omnipotence and control, Robert Charles Mann’s art expresses profound humility and atheistic spirituality contemplating the cosmos with silent wonder.

Looking through the book, I find myself absorbed and challenged, but not challenged in the confrontational or aggressive way. The challenge is more subtle, more gentle and more pleasing. If I did not know what these images were, I would approach each of them simply as beautiful abstractions of light and color and shape. While there are occasional solid references in the images—trees and hills and a pond and such—the main character in nearly every image is the varying shape of the arc of the sun passing in front of the camera.

However, do the math. Six months is roughly 180 days. One hundred and eighty arcs of the sun across the sky, each one held in a single frame. What you get in that single image is perhaps not the passing of time, but the presence of time. It’s a humbling idea.

Some of the images are, to use an inappropriate word, flawed. Something has happened to the film or the position of the camera, and yet each of these elements adds to the narrative held within the frame. The use of colors, both warm and cool tones, gives a dynamic presence. Several of the images have dynamic splashes of red, others contain broken sweeps in the arc, and yet none of them are disquieting, at least not for me. They are complicated, innuendo-filled, evocative.

As might be expected from a master printer, every plate is exquisite. I have no idea what Mann’s post-production may have included. But here, while a pinhole camera has a soft focus, the color-range and the shape of the transit—sometimes clear and at other times broken or morphed—create an emotional content it is a joy to meet.

Sadly, we don’t have a word for the invitation to consider both the particular and the general at the same time, but that is the feeling I get looking at these images. I focus on a small detail, and yet, in the act of doing so, do not give up an appreciation of the entire frame.

Looking at these images, at first I was reminded of Walt Whitman, in “Song of Myself, 51”—

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

But then another comparison (or several) came to mind. Remember the time-passing sequence in the 1960 Time Machine movie, the way the mountains formed and eroded around him? (Note: that movie won Academy Award for Best Special Effects.) Remember the final scene of 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Dave is spiritually reborn? Remember several moments in Interstellar?

There is both tremendous action and tremendous peace built into these experiences, and that is the feeling I get with Solargraphs. The images are beautiful. They ask us to consider the universe, the scale of the universe, at a different speed. They provide an insight that only the long view can provide.

This is an extraordinary project. Set up a camera, leave it open for a very long time, see what happens. Work that exposure into something immediate and present.

Create something that speaks to what we intuit about eternity.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.