A photographic retrospective is a complicated offer.

Both about the artist and the environments within their lens’s range, the work has a doubled subject. There is the artistic biography of the photographer, and there are the subjects and themes of their photography. If we paraphrase Barthes as well as Leibovitz, that all photography is autobiography, this doubling would seem essential to understand an image.

But it is possible to emphasize one over the other.

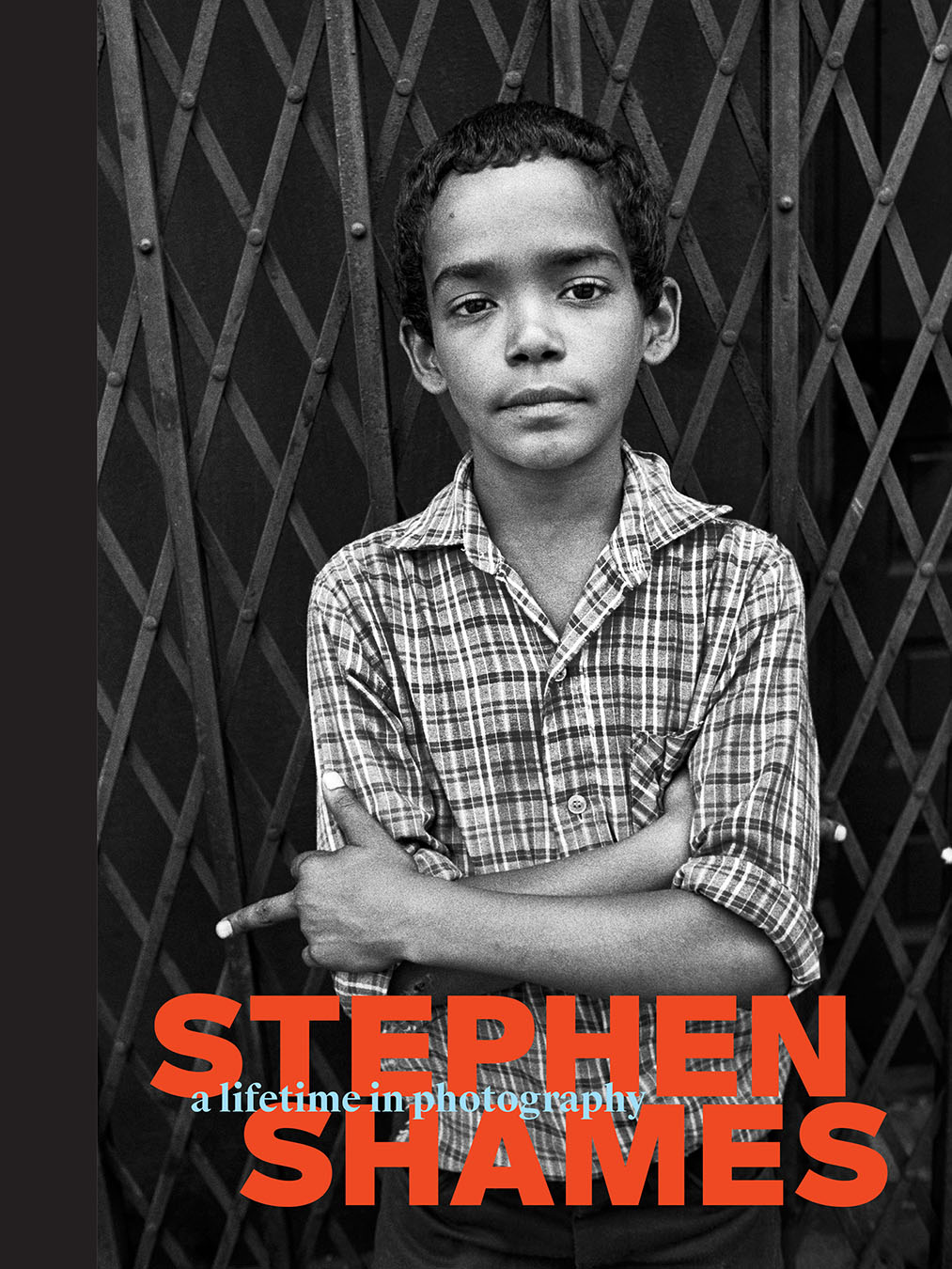

Stephen Shames: A Lifetime in Photography

Published by Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, 2024

Review by W. Scott Olsen

At the beginning of Stephen Shames’ book, Stephen Shames: A Lifetime in Photography, photographer and editor Jeffrey Henson Scales has this observation:

This book is not a survey, nor is it structured with a narrative art. It is more a collage of Shames’s life as a photographer, a mash up of his life’s work. Documentary photography by its very nature is constructed of people, places and things the artist finds in their camera’s viewfinder. Like the many artists throughout history of modern art who have created assemblages of found objects, this book similarly takes the images Shames has created over decades and remixes them here to present a nonlinear view of his own life in photography.

It’s an interesting decision. If the book were structured chronologically, the prime focus would be on Shames—his evolution, development, and insights. The images would be evidence of his practice and craft. And, as a result, we would firmly place some images, and thus some ideas and issues, firmly in the past. After all, Shames has been photographing for more than fifty years.

But to organize the book differently—a collage, as Scales describes it—changes the focus of the whole project, even though the images may be the same. Shames’ aesthetic biography takes a bit of a back seat to his work itself. Everything is now. The images carry thematic weight, as they were always meant to do, more than biographical placement. And what happens is that a tone, a theme, a way of looking begins, including the cover and endpapers, and slowly grows in depth and strength as you turn the pages.

At the end of the same introduction, Scales writes:

In assessing this retrospective of the work of Stephen Shames, it is impossible not to be moved by his journey and his commitment–not just to the urgency of photographic situations, but also to his obvious love and respect for the humanity of his subjects, while also documenting some possible solutions to vexing problems that continue to this day.

Shames’ love and respect for people who struggle are the real subjects of this book. The gathering of his images into a book, and our doubled understanding, makes the contemporary examination a gift.

At the beginning of the book, in an introduction, Shames writes:

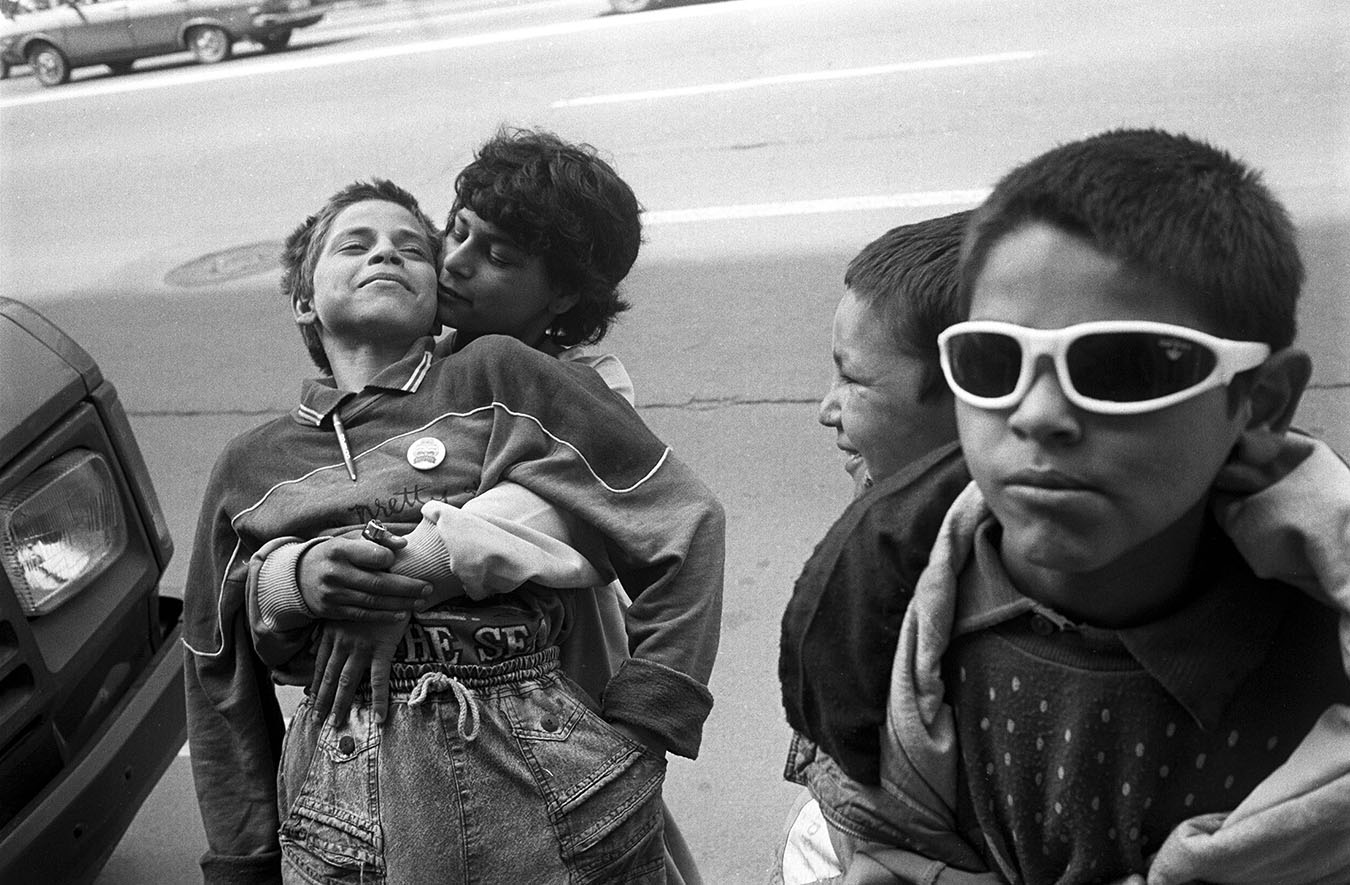

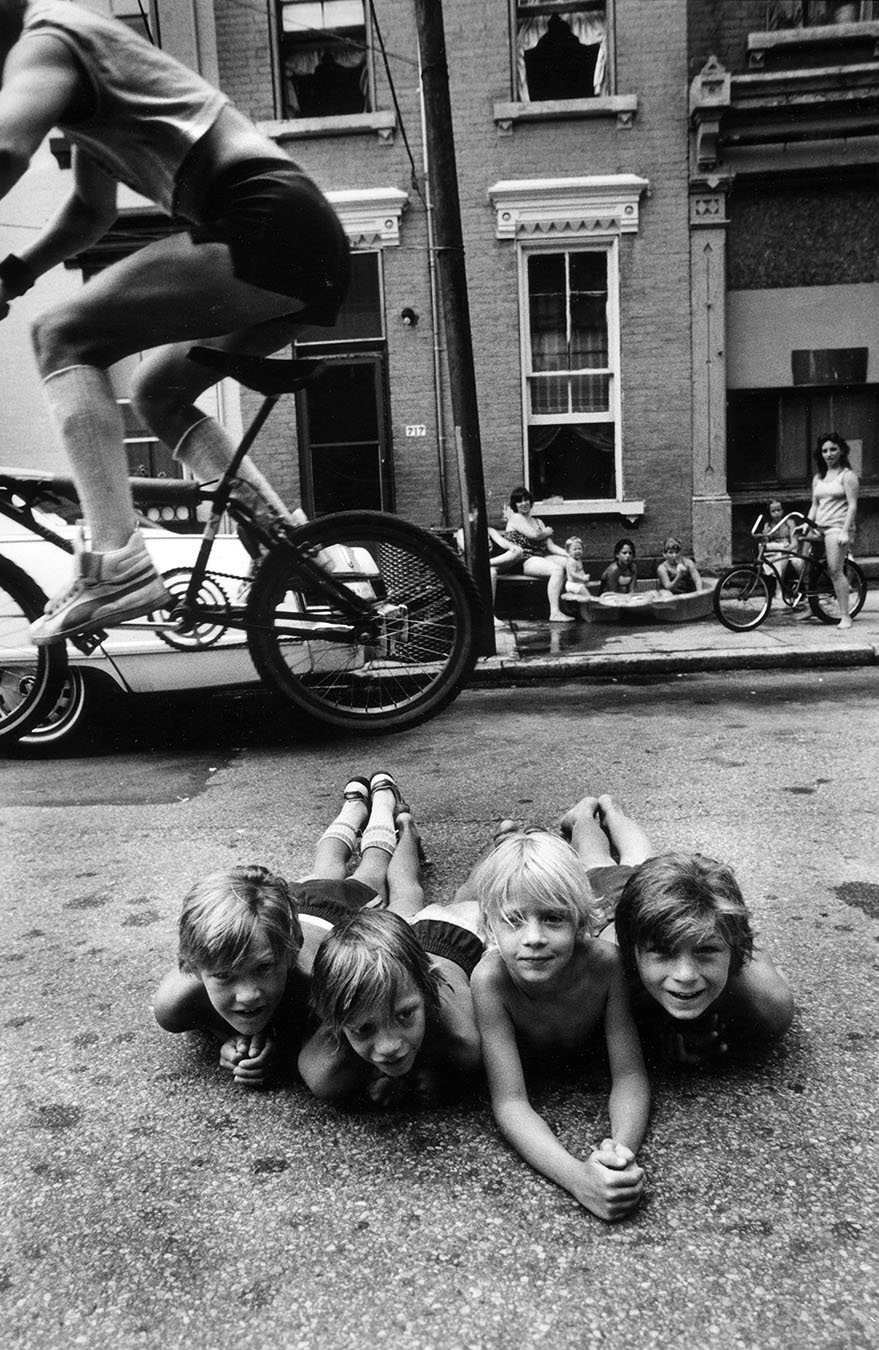

I have been a photographer for more than five decades. I have traversed five continents, witnessing tragedy and triumph. Although I photographed many diverse subjects and pictured people from countless cultures, there is a thread connecting my pictures. Much of my photography is about children in distress, with a focus on identity and family: what tears us apart and binds us together—violence and abuse, but also sensuality, love, hope, and transcendence.

A short while later, he writes:

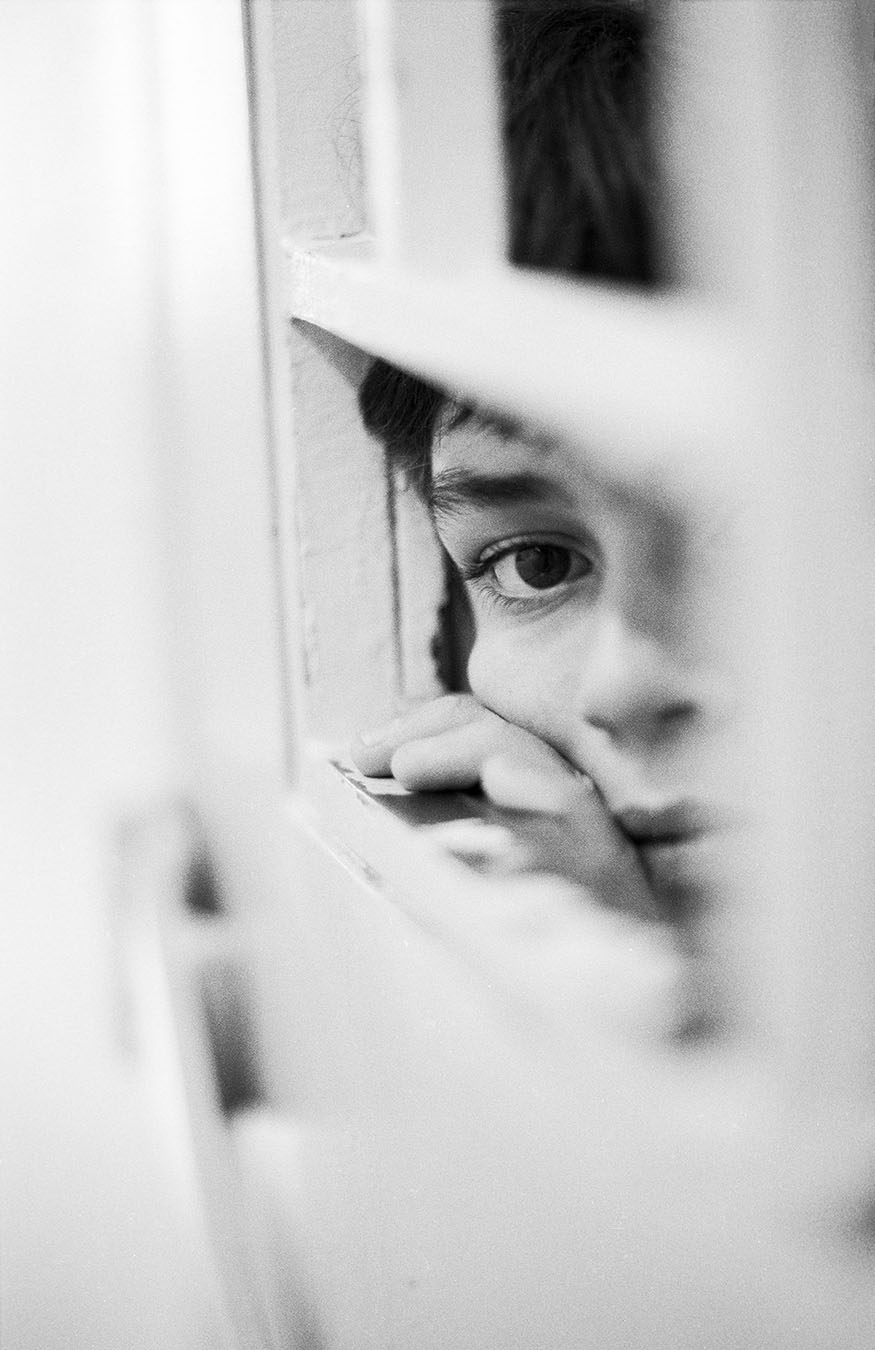

While my work fits into the documentary tradition, it was also about the edges of experience, where things are more ambiguous and nonrational: the inner moments where public events meet our private fears and hopes. This, in my opinion, is where the action is, the place of art.

Stephen Shames: A Lifetime in Photography is an important and necessary book. Here is a retrospective of a career spent documenting issues local as well as global, psychological as well as sociological. And in the very best sense of the documentary tradition, the work shows us to ourselves in ways that provoke deeper questions.

From Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers to Outside the Dream: Child Poverty in America, Shames has found a photographic voice to witness. Keep in mind, “to witness” means two things. It means both to see and to say. This, I believe, is the highest calling, responsibility, and reward of any kind of photography.

Although the book is not structured with an arc, it is divided into distinct sections. The few color photographs are set off from the great many black and white photographs. And there are recurring themes of poverty and violence. But going along, there are also moments of great tenderness, love, and surprise.

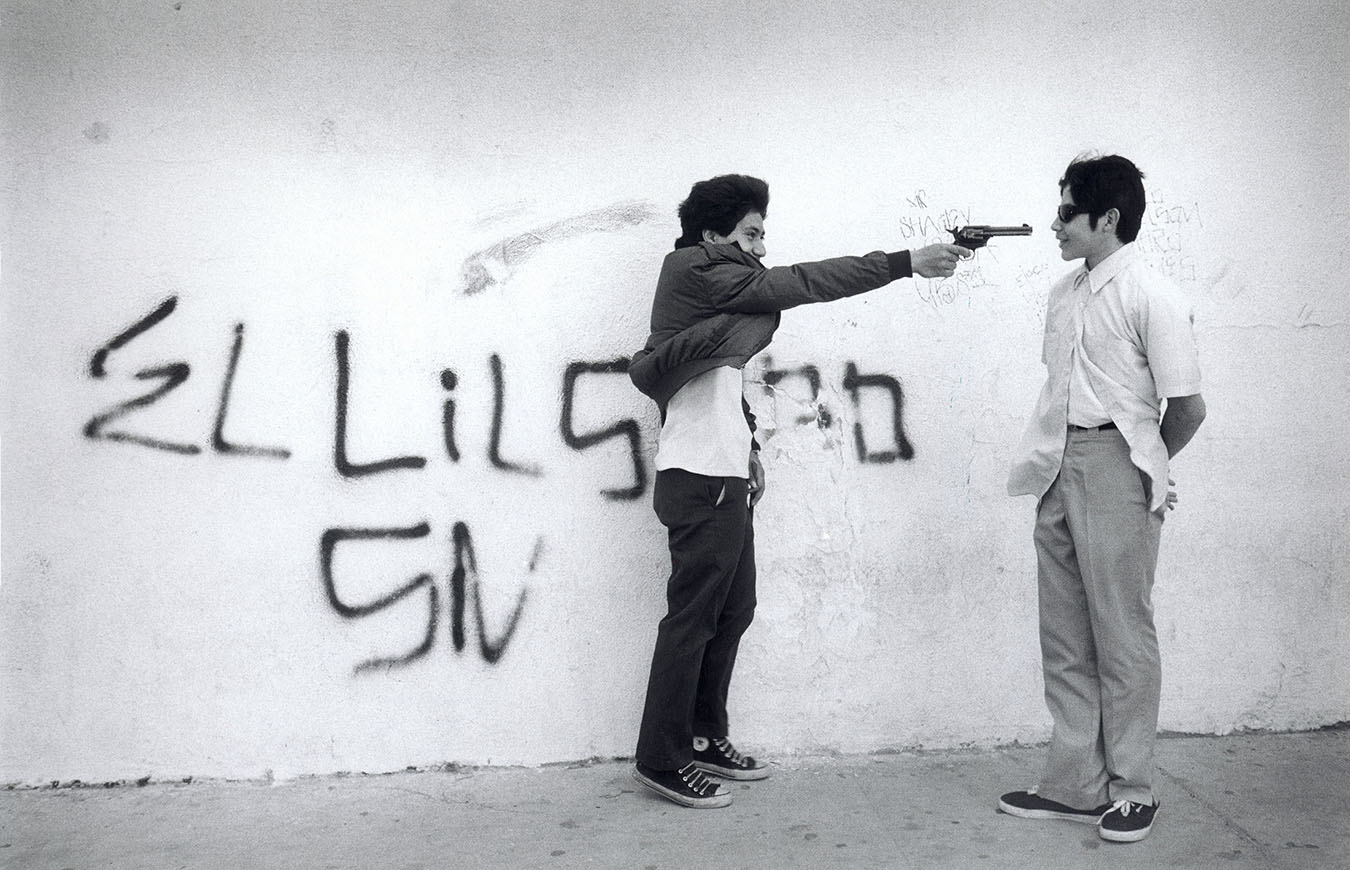

The collage often brings surprise. There are bodies on the street, children in Halloween costumes, lovers embracing on a beach. Suddenly, there’s Barack Obama or Stephen Hawking. A short while later, one boy points a cocked gun at another boy’s head. Some of the images contain great irony, such as a fourteen-year-old being arrested for selling drugs, pressed against a wall underneath an ad for Marlborough cigarettes, and a poster with an affectionate couple.

But the real power of this book is a bit different. Think crescendo. Or better yet, think of something like the finale to the Firebird Suite, or Aaron Copland’s Simple Gifts. There is a feeling, first of sadness, perhaps anger, a bit of being disturbed. And with that comes a counter idea. We are always angry because we have something else in mind, something better, something closer to peace. What this book offers, as a result of everything else, is a love story.

More than 50 years of photographing struggle. This is a life spent building empathy for the people in these pages and, through them, for humanity in general.

Every image here is extraordinary. Most of them are black and white, grainy, sometimes out of focus, and they carry the electricity of photojournalism. There are dramatic moments as well as moments so subtle I find myself lingering on the page in both admiration and awe.

To focus on a difficult situation is not to accept it. Instead, it is to call attention to it so we can learn, and our world can change

Many of the images in this book, although they are all candid, carry the weight of portraiture. They invite us to examine the faces, the body language, and the expressions of the people within the lens’s field of view. Very quickly, everyone in this book, from the mother holding a newborn to the shackled ankles of a prisoner, becomes an individual and a narrative.

Photography has that thing about it. Capturing a small moment signifies the universe. And whether it’s violence or love, it is our universe. The image defines it.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.