Sometimes a truth is disturbing.

Yes, sometimes a truth is not the whole truth. It is not universal in its consideration. It is, instead, a truth about a small element. But that small element, seen honestly, has a ripple effect. It expands and influences our understanding of the whole.

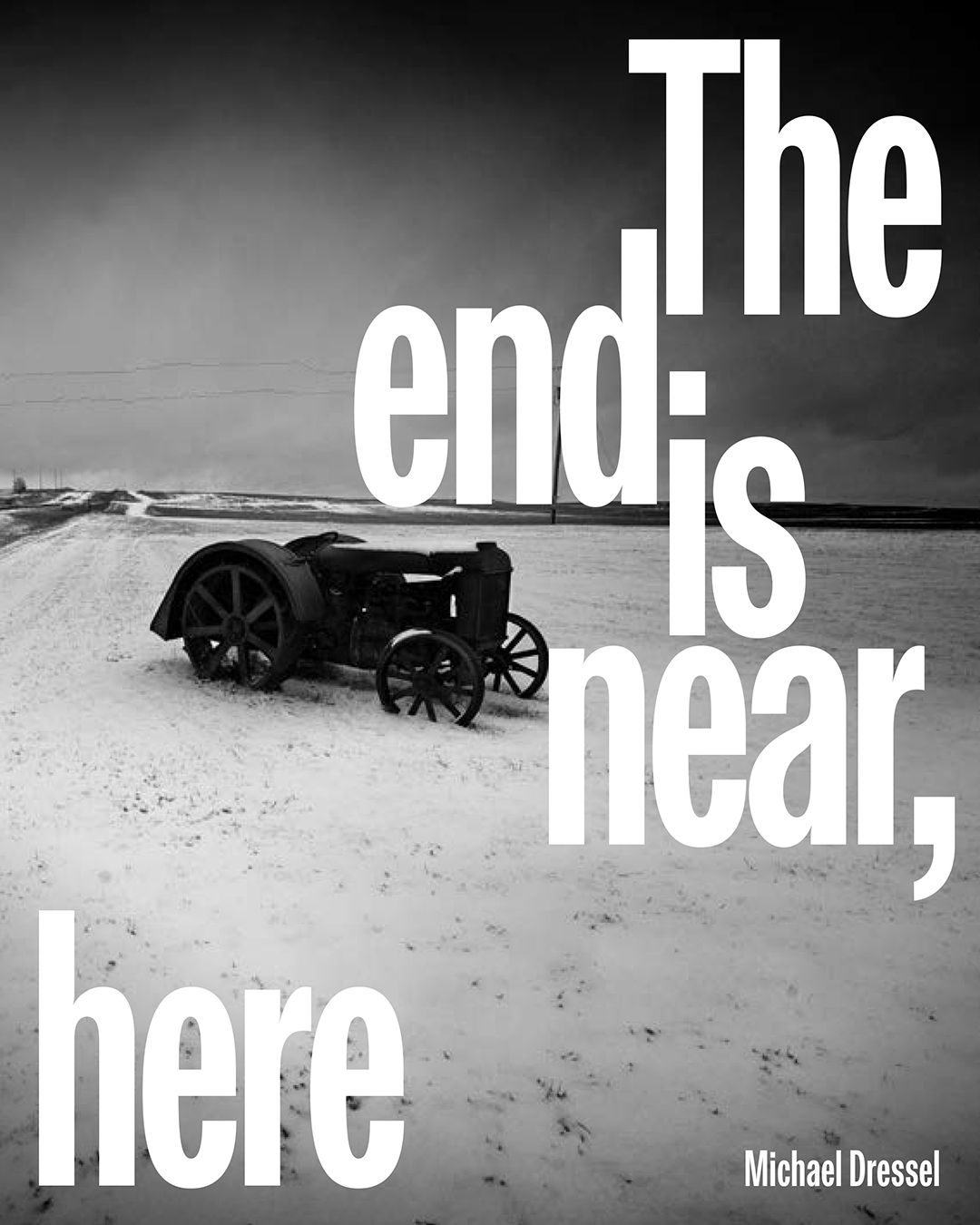

“The End is Near, Here” by Michael Dressel

Published by Hartmann Books, 2024

Review by W. Scott Olsen

This is one of the powers of photography. By framing a subject, by calling our attention to a specific area, we are oftentimes asked to look at a limited view as representative of a larger theme, a larger issue, a larger problem.

The End is Near, Here by Michael Dressel is a disturbing book, and I mean this as a compliment. This book does one of the things photography can and oftentimes should do. The book looks deeply and honestly at a part of our world we know is there, but most often ignore. I cannot say the book is an act of revelation, because every page is familiar. Instead, the book is an act of attention. This book is evidence of who we also are.

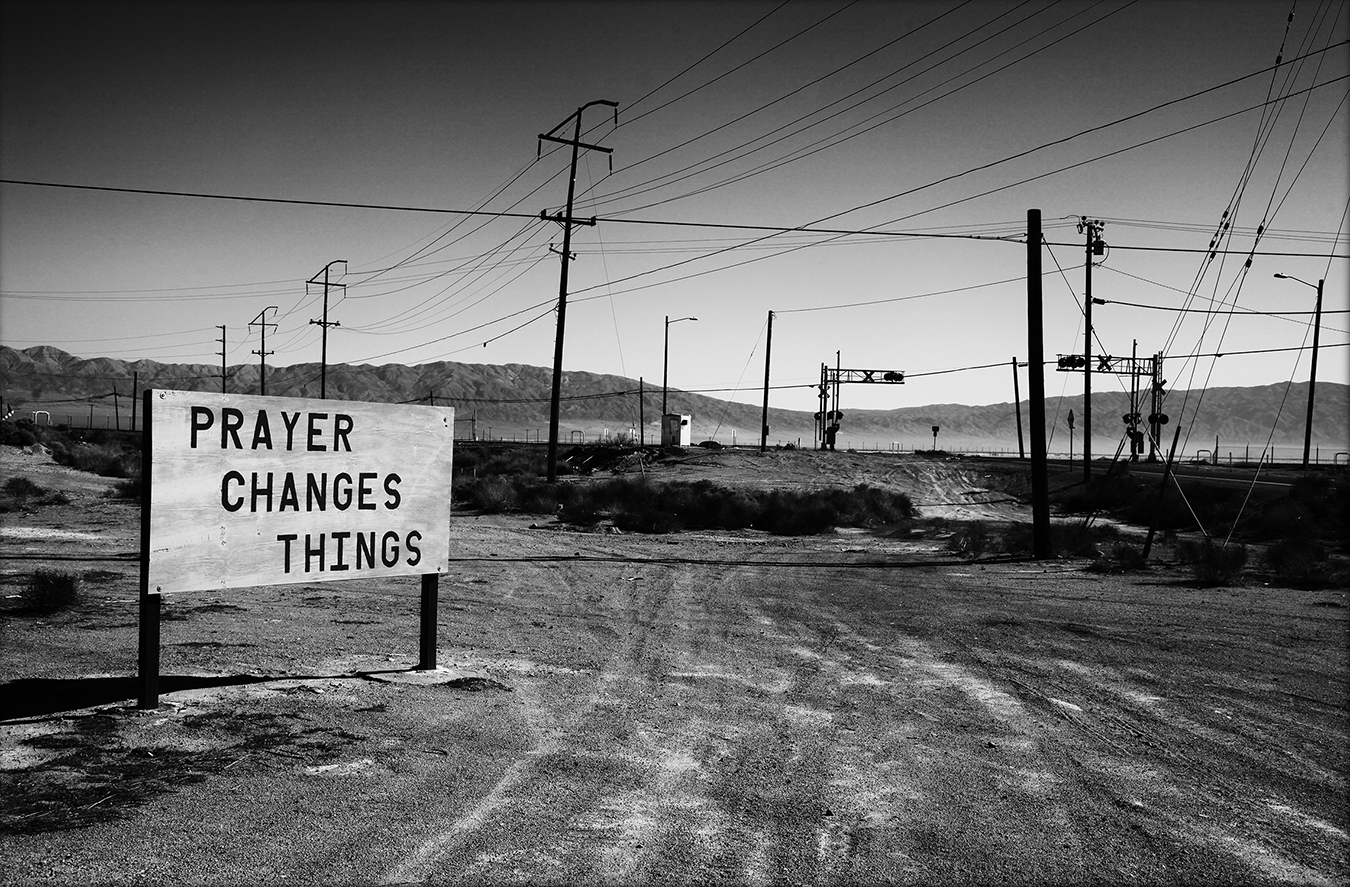

The End is Near, Here is a series of black and white images which show the United States at a time of intense division and crisis. Not just political crisis, but moral crisis, social crisis, psychological crisis too. Our gestalt is fractured, and this book is evidence.

Inside the back cover, in an essay by F. Scott Hess, Dressel says—

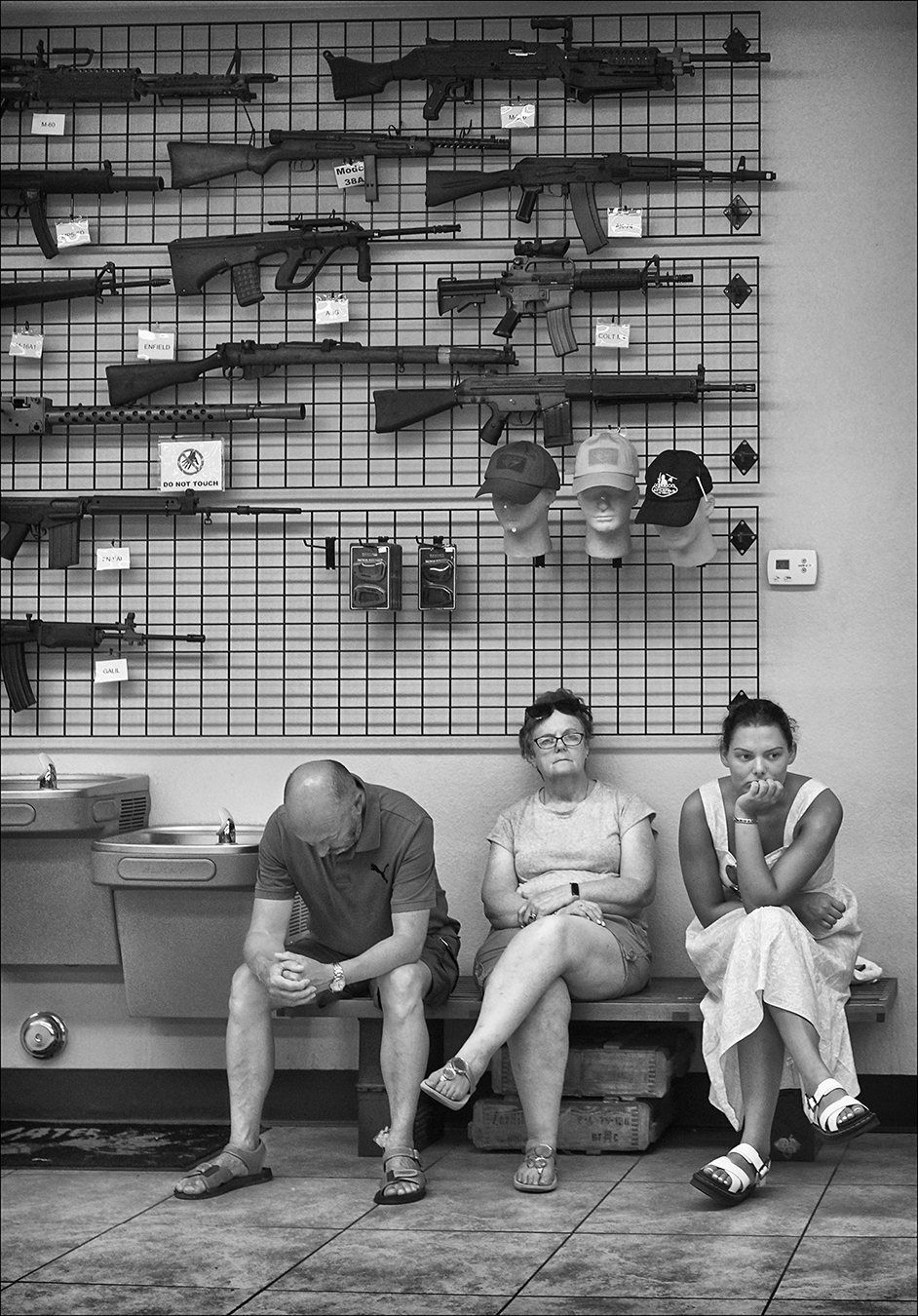

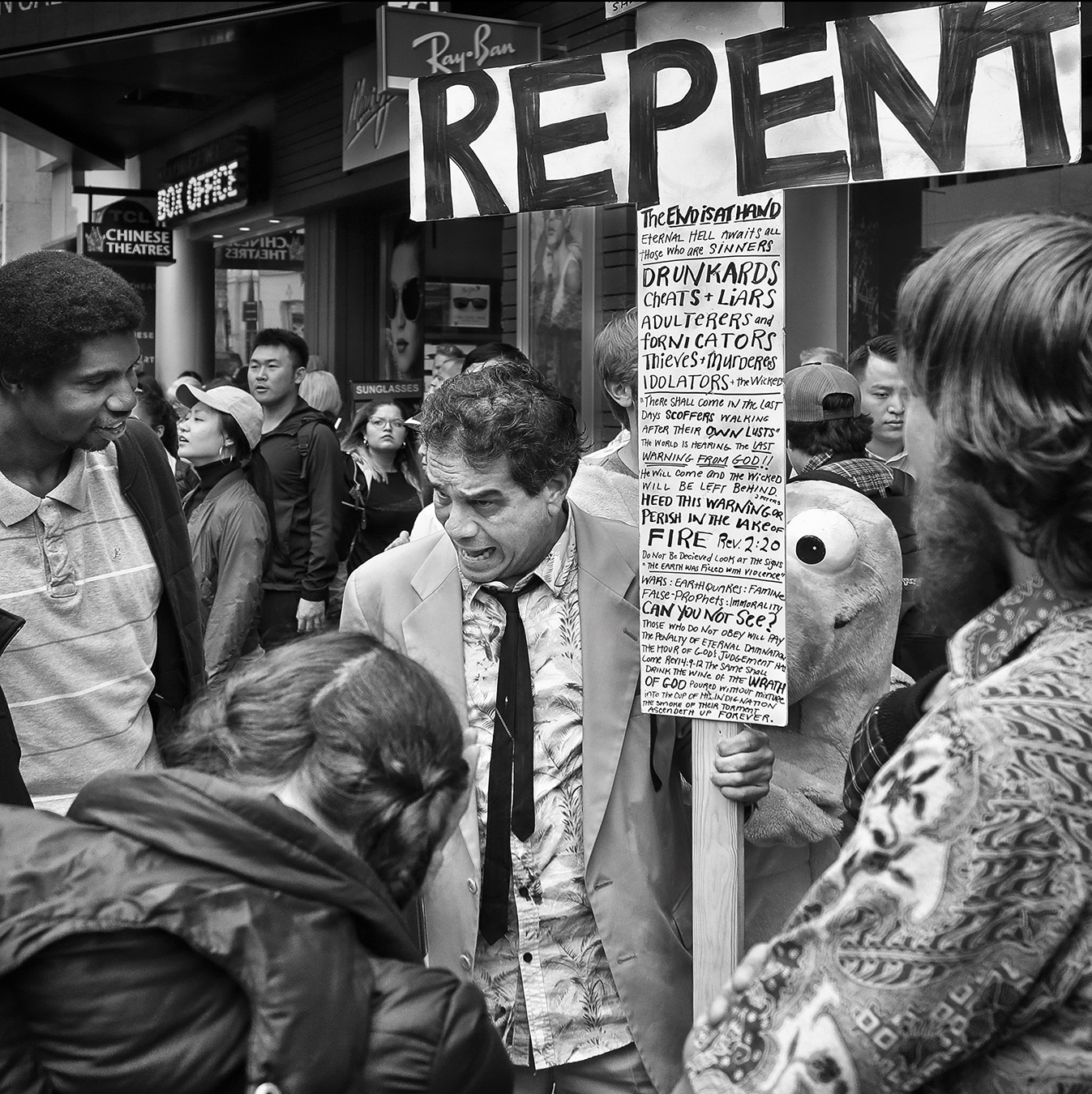

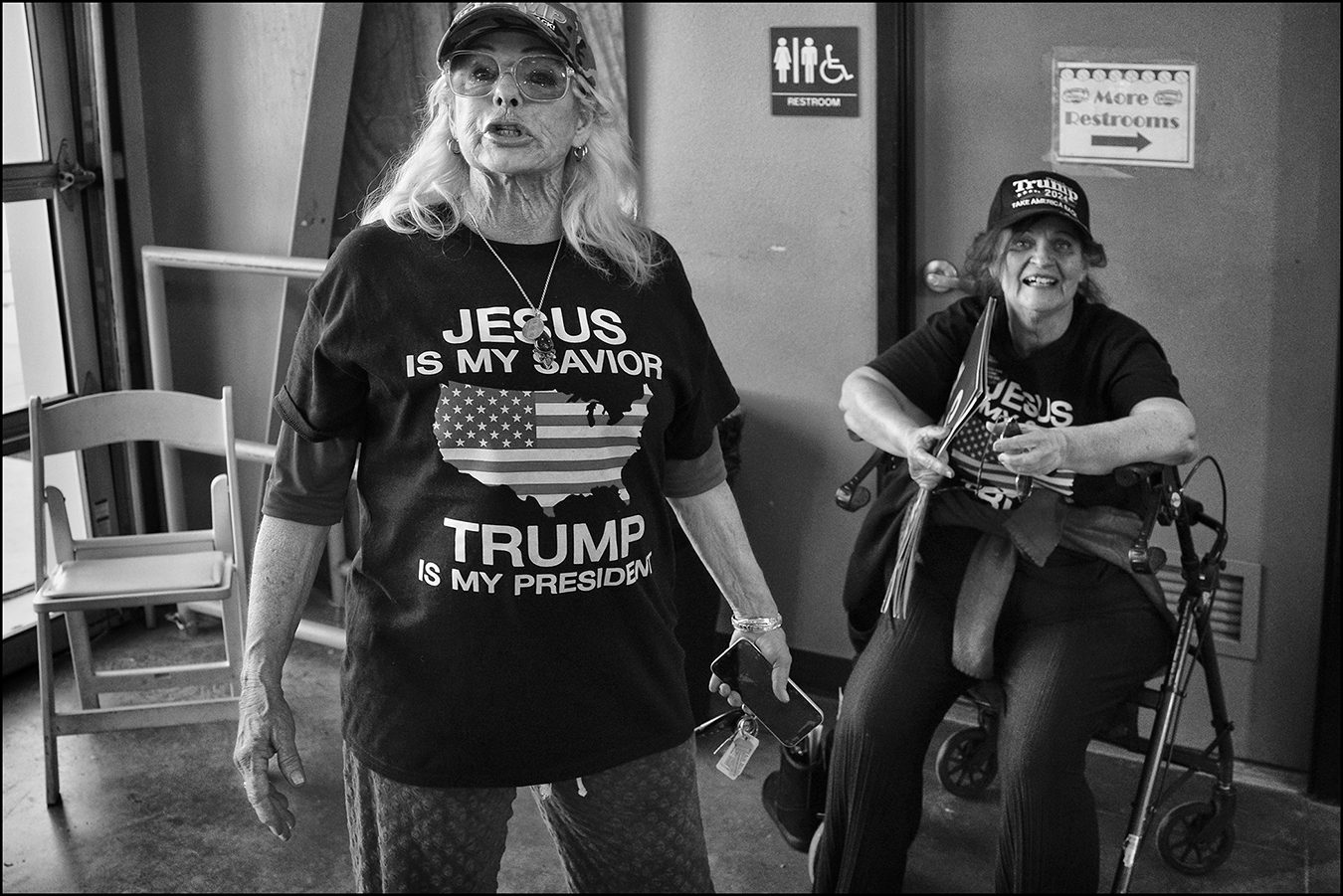

The elements that jump at me everywhere are poverty and decay, extreme nationalism, omnipresent religion of the kind that would be considered psychopathic cults in other places, gun craziness combined with aggressive paranoia and general moral decay. Not a happy combination.

The first hint that this book has an uncomfortable truthfulness comes from the title, which is an interesting play on words, or at least on grammar. The End is Near. We’ve heard that a thousand times. Time to repent. But add a comma and the word “here” and not only are we at the end of times, we’re in the neighborhood where it ends perhaps first.

Inside the book’s front cover, there is this description—

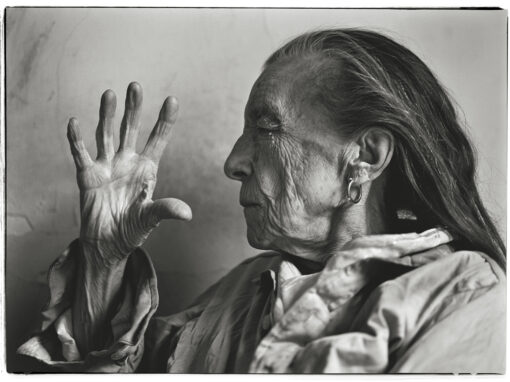

Dressel’s images show a society on edge, marked by extreme nationalism, political polarization, religious fanaticism, and gun mania coupled with paranoia, pervasive poverty and moral decay. His portraits are complemented by landscape photographs that speak their own gloomy language.

The text of the book is in both English and German, representing the two bits of Dressel’s history—he was born in East Berlin and spent two years imprisoned there before moving to Los Angeles. The point is made that this two-part definition allows him perspective, allows him to see things others might gloss over because they are so familiar. F. Scott Hess’s brief essay at the end gives valuable historical and aesthetic information. He begins—

There’s a special place in hell reserved for Michael Dressel. He’s allowed to visit venues most of us are terrified of and bring his camera to record Hell’s inhabitants as we rise through our agonizing daily encounters and routines. His self-imposed contract does not permit him to blink, to remove his eye for a moment from the bizarre contortions that hide in the recesses of the normal…

Dressel is aware of the history of landscape depiction as a vehicle for expressing human emotions and desires, and feels his viewers share an instinctual grasp of these scenes, understand his viewpoint, and even get his dark humor. He says, “The American landscape of the West displays for me the hardness and mercilessness of the universe. Sometimes you might as well be on Mars and, in a way, you are.

The problem—again, this is meant as praise—with this book is that every page has dysfunction, every page has irony, pathos, sadness, despair, and looking at every page, the impression I got was one of familiarity. I have seen these things. These images are true. They are not what I like to admit or dwell upon. These are the things we gloss over, hoping they will go away on their own. We suffer through them, like a bad cold, with the hope that recovery is just around the corner. But the problem is, recovery is not just around the corner. Something is more deeply wrong.

The people and places in this book have been with us forever. We just don’t like to look at them. The guns, the crazy people, the exploitation, the ignorance, the poverty—these issues are replete throughout the book, and the disturbing part of it is that on every page, I am asked, compelled to admit, yes, this is us.

It is not all of us. It is not the best of us. But neither is it foreign or irrelevant.

Photography, especially documentary photography, can be instructive. It can illuminate our failings as an indictment and also as a call to action.

This book is both and, for that purpose, it deserves a place on every table. We can tell our stories. Tell ourselves stories of greatness and hope and promise. But just like the children hiding under the cloaks of the Ghost of Christmas Present, a boy named Ignorance and a girl named Want, there is a troubling part of us near here. They are the heart of the lesson.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.

Pascal

April 2, 2025 at 20:39

Thanks, Scott. In this particular time in our history, this book brings a lot of meaning and reflection.