Daido Moriyama is still considered to be one of the most iconographic Japanese photographers, whose images have propagated the Japanese way of life in the collective imagination of the entire globe, with a totally modern and Western declination.

It is to this extraordinary photographer that the Photo Elysée in Lausanne is dedicating a remarkable tribute, with a retrospective that will end on 23 February 2025. Already exhibited in London, the Moriyama Exhibition received an overwhelmingly positive verdict from ‘The Guardian’, which called it the best photography exhibition held in London in 2023. The organization of an event of this level involved partners such as the Moreira Salles Institute of Sao Paulo ( IMS) in collaboration with the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation, and the participation of Yutaba Kambayashi, Satoshi Machiguchi, Kazuya Kimura, with the assistance of Daniele Queiroz (IMS).

So let us ask ourselves why Moriyama’s work is so fundamental to the history of photography and yet remains so relevant today.

Moriyama was born in Osaka to a family of humble origins. A factory worker, father, and housewife mother, the family moved around a lot for his father’s work until the latter died, leaving a young boy who was not doing well at school but was attracted to design and film. Soon the young Daido moved from his hometown to Tokyo, where he wanted to work as a photojournalist, and like any fan of the craft, he began to beat the city far and wide.

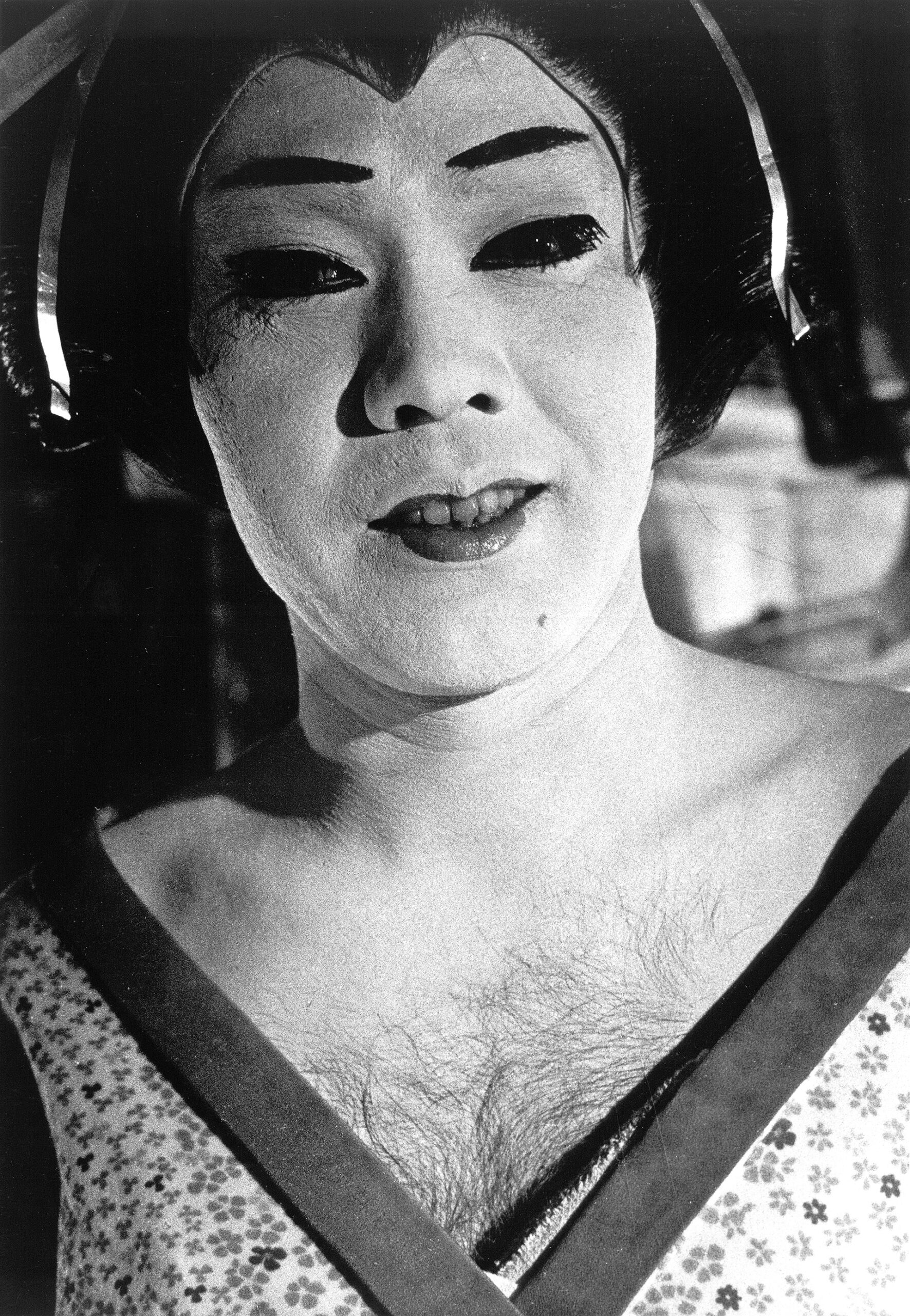

© Daido Moriyama, Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation.

Initially, he devoted himself to documentary photojournalism images that soon evolved into desecrating images. She suddenly strikes the viewer, like Aomame, the protagonist of 1Q84, a novel by Haruki Murakami, also set in Tokyo, with a story imagined by one of the writers accused at home of being among the most Western in the country.

Moriyama is also considered a cosmopolitan and international photographer, but this is certainly not a boast in 1970s Japan, which was particularly protectionist, both towards traditions and the preservation of a crystallized image of the nation and reality. Indeed, conservative Japan remains static, but everyday life is remarkably dynamic.

Between 1968 and 1972, Moriyama traversed the streets of Tokyo with a benevolent eye toward his city and immortalized the most modern trends in the Japanese metropolis. His favorite spot is Shinjuku, a district where life teems, full of people at all hours of the day and night. Daido maintains that everything has the same value in front of the camera, and so with his inseparable Reflex camera, compact and handy, he shoots all the time, sometimes not even putting his eye on the lens, to go unnoticed. Thus are born the ‘are, bure, boke’ (grainy, blurry, out – of – focus) images that are characteristic of his artistic narrative. Immediate, not always well-focused shots in which the intense, blurred blacks and whites do not take on the connotation of bleaching, dodging, and burning as in Dave Heath in some of Gary Winogrand’s more innovative shots.

In Moriyama, the images are total, blatant, explicit, and unfiltered. The large portraits of Kabuki actors, rather than the erotic images of sex club protagonists that appear in ‘Provoke’ magazine, become the irrefutable declaration that Tokyo is changing, that promiscuity has taken over even the demure Japanese, and that Western trends are engulfing their most populous metropolis. ‘Provoke’, in particular, will go down in history for its prominent role in the period of political protest at the time.

Together with Takuma Nakarita and Yutaka Takanashi, the poet Okada, and the art critic Koji Taki, Moriyama took part in the creation of a magazine (Provoke) whose subtitle was Provocative Materials for Reflection. In it, innovative photos were opposed to the mere function of photojournalism, and in particular, in the issue of the magazine entitled ‘Eros,’ Moriyama would focus on the combination of images and fetishism, laying bare, in the literal sense of the word, the most hidden erotic uses of Japanese.

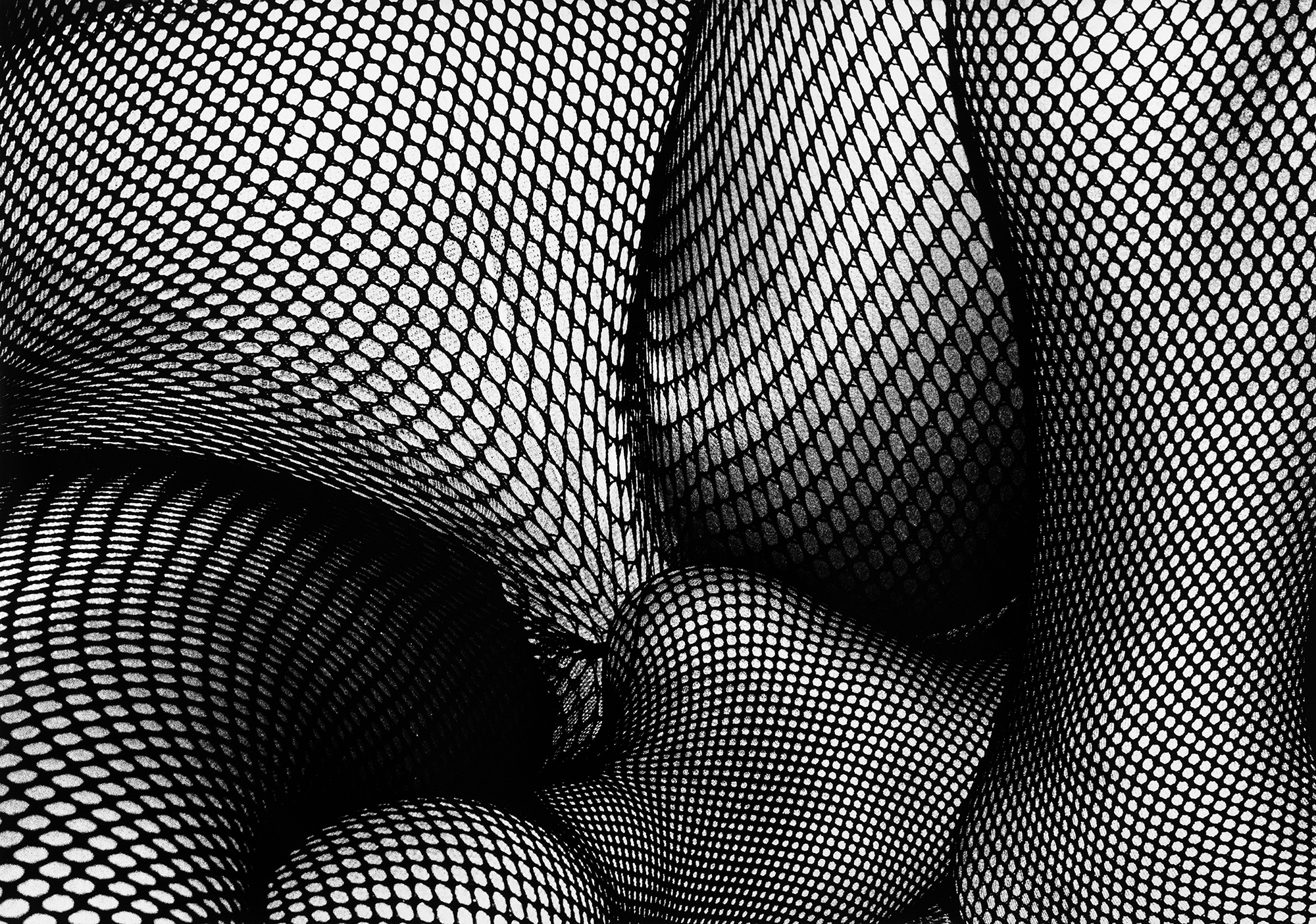

Certainly, Moriyama is an elegant, unabashed photographer, but always fundamentally non-pornographic. He will never go so far as to show the extreme rituals characteristic of Japanese bondage, such as the shibari photos taken by Nobuyoshi Araki, but will limit himself to imprinting on his film images of sexy, lascivious women, or intimate views of fishnet stockings in which what is imagined becomes incredibly more powerful than what can be explicitly seen. Moriyama’s photography was contaminated by Andy Warhol’s Pop art photography through a working contact between the two that resulted in an irrefutable inspiration for Moriyama. Warhol’s 1963 photo ‘White Car Crash 19 Times’ is extremely similar in subject matter to Moriyama’s 1969 ‘Midnight Accident’.

In fact, Moriyama began a collaboration with the magazine Asahi Camera in which his photography was put at the service of reflecting on the distance between real effects and their images, such as in the case of car accidents, crime news, tabloid newspapers, and the social transformations induced by the westernization of the country. Again, through the use of his trusty Kodak Tri-X, Moriyama challenges the image of contemporary photography, questioning the role of photographers and their social weight in spreading the news and propagating the most fashionable trends.

The great photographer’s career was not straightforward, at times and even for long years, so much so that he suffered from depression and thought about quitting photography. ‘I tried to demolish photography, but I ended up demolishing myself,’ says the great photographer, and indeed an inevitable attraction towards this medium of expression, so fundamental to his life, brought him back on his feet. Ultimately, Moriyama’s artistic activity remains substantial for contemporary Tokyo photography, thanks to the experimentation he inaugurated, which nevertheless always conceals a clear meaning behind it.

Some iconographic images of his artistic activity, such as ‘Stray Dog’ of 1971, while referring to his past and awakening the memory of his childhood and the dog of his family of origin, actually highlight an ontological symbolism of Japanese culture. In this photo, the duplicity of meanings is expressed between the reference to the classical iconography of dog loyalty, also symbolized by the famous Hachiko statue in Shibuya, and the artist’s very personal recollection, in which the image of the lonely and sad dog stimulates an immediate empathy in the spectator, emphasized by the dog’s pose and the sharp colors of the photo.

Daido Moriyama has ultimately dictated a genre that still today continues to be particularly followed by contemporary photographers, halfway between photo-reporting and visual narration, emphasising certain elements of contemporary society, and paving the way for an innovative interpretation of the image that has led in recent years to a more fashionable and popular declination of this genre, such as street style.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Silvia Ionna is an independent Art Director. She writes about photography, art, and books for various online magazines.