I remember a soft spring evening several years ago, before the pandemic. A man named Andrew Steinberg, a tremendously gifted organ and piano player who teaches at the college where I teach, hosted an evening of jazz at a local restaurant, and he brought with him a young woman, an undergraduate with a remarkable voice. The evening was jazz classics and occasional show tunes. And it was one of those springtime evenings filled with good music that can make your soul smile.

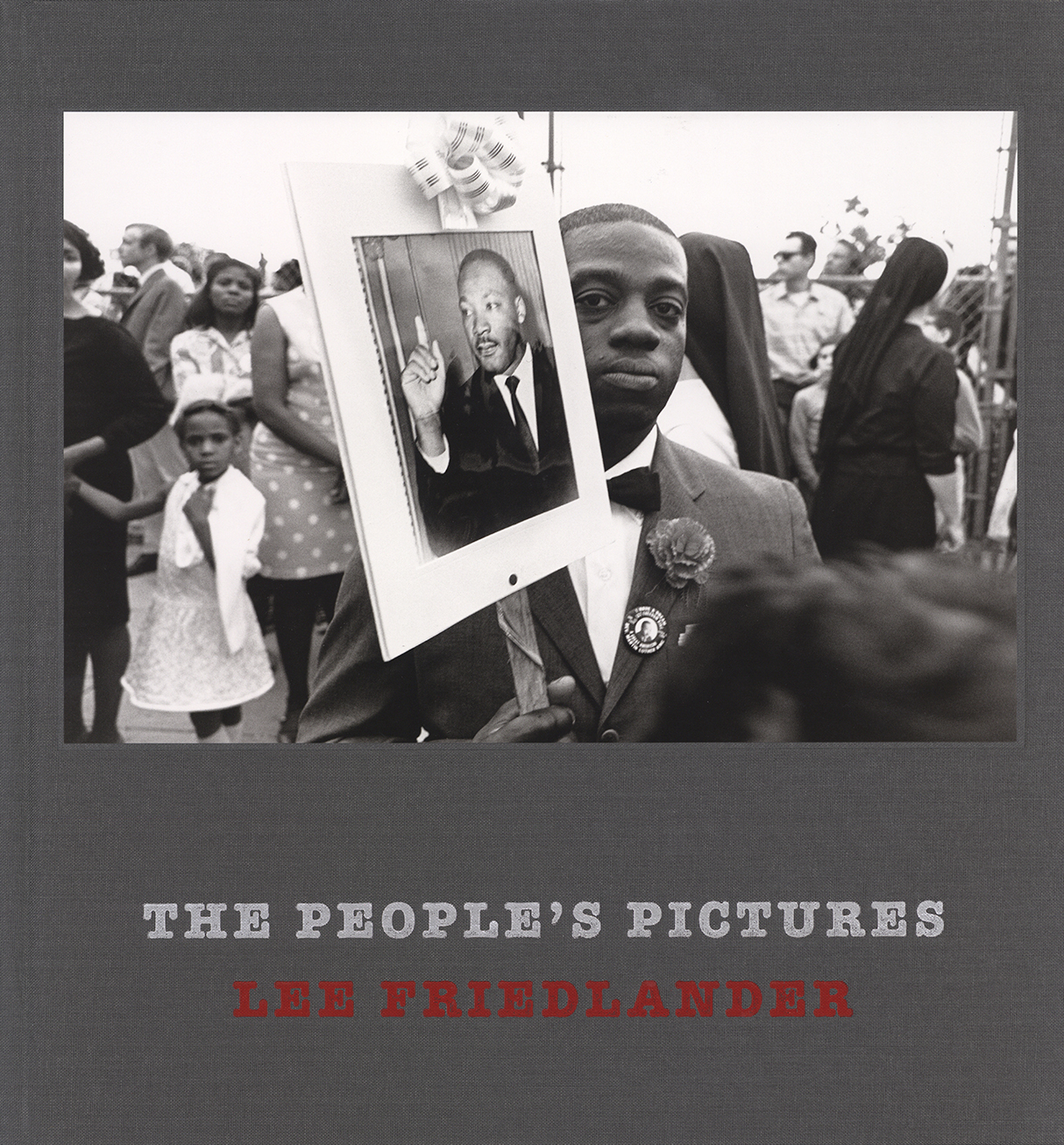

“The People’s Pictures” by Lee Friedlander

Published by Eakins Press Foundation, 2021

review by W. Scott Olsen

But what I remember most about that evening is something I missed. In the middle of a song, I don’t remember which one, Andrew was playing a solo and suddenly several other members of the music department faculty, who were there to enjoy the evening too, broke into smiles. They heard something in Andrew’s playing I did not.

It could have been a quote. It could have been a technical flourish. Even though there’s a lot of jazz in my own background, I did not hear what they heard, though I heard exactly the same notes, in the same room, at the same time. While we all enjoyed the tune, something about their depth of experience created a sense of pleasure that was inaccessible for me.

I’m thinking about this because I have on my desk a copy of The People’s Pictures by Lee Friedlander. People who encounter this book who are not photographers, in much the same way that I am not a musician, will enjoy this book and find it interesting. People who are photographers, like the other music faculty that evening, will find this book comic, poignant, sad, complex, and often profound.

Comprised entirely of black and white images, the book is divided into two halves. The first half is all pictures of people taking pictures The second half is pictures of pictures, mostly portraits.

The Peoples Pictures is a book about photography, but not in any technical sense. The images span the entire globe. There is China, South Dakota, Italy, Massachusetts, Paris, New York City, Monte Carlo, the list goes on. And even though there is very little text in the book at all, just two epigraphs, it is a compelling critique of the act of taking and encountering images.

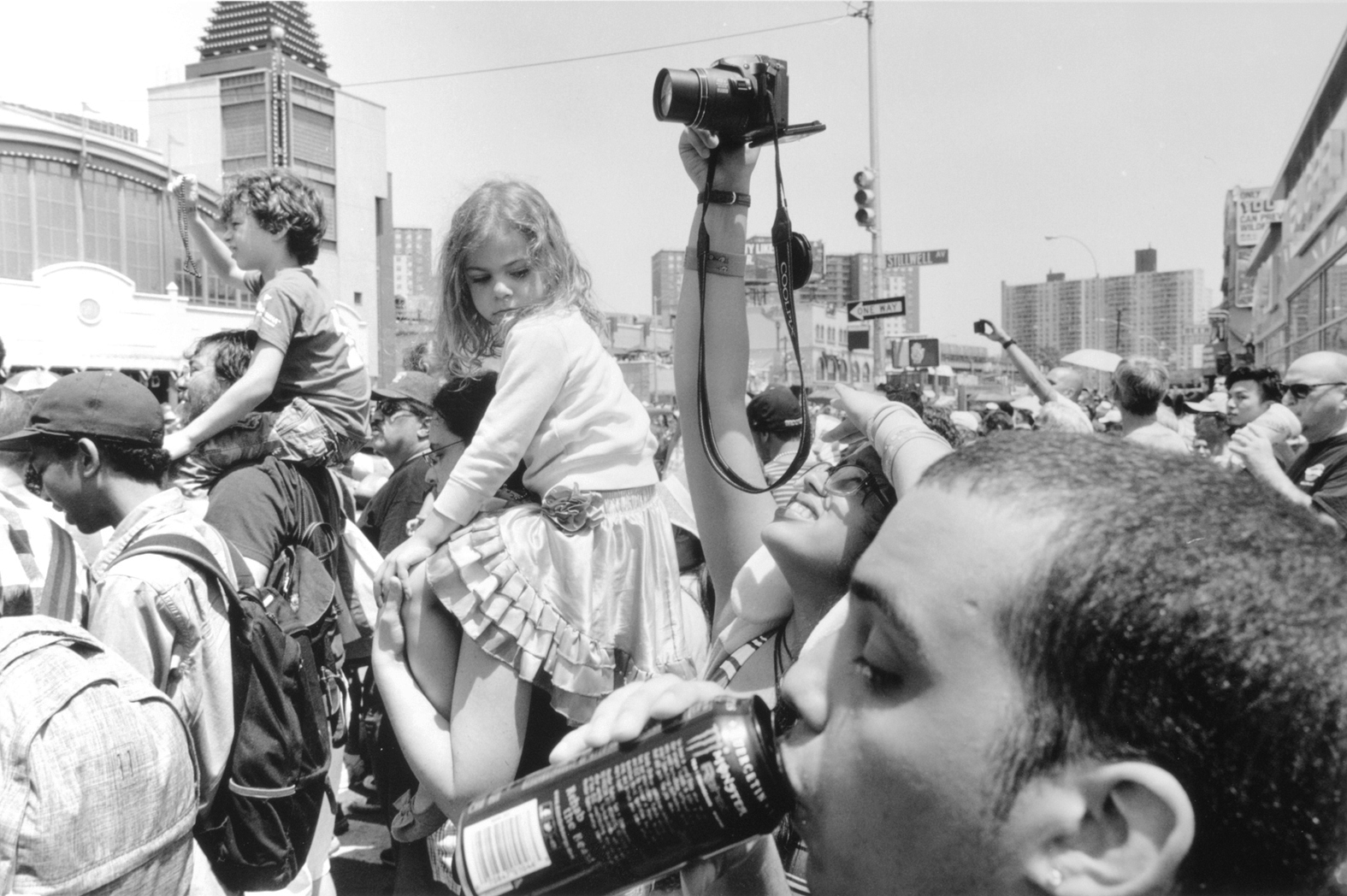

As I said before, the first half is it collection of black and white images of people taking pictures. Sometimes they are professional press photographers. More often than not, the people pointing a camera are amateurs holding everything from old Kodak Instamatics (both 35mm and the slim tele-Instamatic), to classic Nikon F series, to cell phones. There is no text to explain what people are taking pictures of. Sometimes it’s obvious: scenic vistas, a bicycle race, tourist shots. Yet sometimes the context is only implied, such as images from Chicago in 1968 which I assume were taken during the troubled Democratic National Convention there.

But, frankly, the subject of the photographer’s aim in this first half is irrelevant. The subject is not even really the photographer. It is the act of taking an image.

What causes someone to raise a camera to their eye? What do we look like when we’ve stepped out of time for that brief moment to capture 1/60th of a second? There is something about these images, especially in black and white, that makes them artifacts of an aesthetic. Artifacts which have anthropological weight.

What do we think we’re doing when we raise a camera to our eye? There is, for example, a picture of a young woman standing in the middle of a fountain in Florence Italy in 1982 to take a picture. What she is taking a picture of is actually out of this image’s frame, so we are left to encounter her setting and wonder what she was after.

There are images of people taking party shots in New Orleans, in San Francisco, and elsewhere which, we can see now, have the aesthetic weight of a cell phone selfie, long before the cell phone. The act of documentation, of historical preservation, is the force behind these images. How strong is the urge to have evidence of our witnessing and participation?

The images also show the contrivance as well as the naturalness of picture taking. Photographers do everything from lay on the floor, to hold the camera above their head, to climb on objects or other people, to get a particular angle. Most photographers simply raise the camera from wherever they happen to be standing and snap away.

What is it we are saving? And what is it that Friedlander’s images are showing us? It’s a bit like a camera pulling back from a movie set and suddenly we can see the lights and cameras and microphones. We realize the artifice, but that’s not the critique. We enjoy the meta-look, the more complicated story, the behind-the-scenes access into the how-it-was-made. The critique here is the examination of an artist at work, a bit like a photograph of Picasso holding a paintbrush and working on a canvas.

The second half of this book is a reverse of the first. Instead of images of people taking pictures, we get images of people encountering pictures. I don’t mean head shots by themselves. I mean head shots in a store window with somebody walking by, looking at them. The subject here is not based around who are the people in the images. The subject here is more about the placement of images and the situations in which we encounter them, everything from billboards to living room walls to storefronts to restaurants. These are not rarified art gallery presentations. The question throughout this entire book is in what situation do we take a picture and in what situation do we encounter an image—and what does looking at these two situations, outside the actual content of the image being taken or viewed, tell us about ourselves?

What is especially remarkable about this collection is the placement of the social content. This is a book about the sociology of taking and encountering images. Better yet, this book is a look at photography through the lens of cultural anthropology. For photographers, this will be an intriguing book to peruse. We will recognize so much of ourselves in here, and so many questions and challenges to what we’re doing, it’s the kind of book well where we will look at an image and then stare at the ceiling for a while in both memory and engagement.

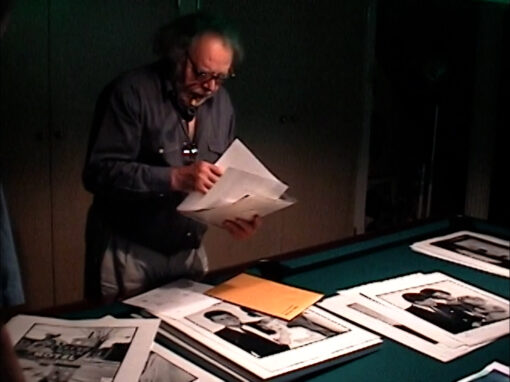

Freelander, of course, is an icon in American photography. He’s garnered everything from Guggenheim Fellowships to a MacArthur Fellowship and Hasselblad Award to lifetime achievement awards. The list of books and gallery presentations is daunting. His aesthetic of the American “social landscape,” asymmetrical black and white images of urban settings, emerged alongside the work of Winogrand and Arbus to define street photography. His attention to reflections and compositional fragments has always rewarded a sophisticated understanding of layers and meaning.

Every photographer should own this book. It may not get much play on the living room coffee table, but it will stay close to our minds and hearts.

Thinking back to the evening of jazz several years ago, we all heard the same music. The musicians in the room heard it deeper. Everyone will enjoy this book. The photographers, having recognized ourselves and our questions and our hopes and our promises in here, will hear it better.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.

michael grover

September 13, 2022 at 11:38

Fascinating!

B. D. Colen

October 10, 2022 at 14:31

An excellent take on a seminal book, Scott. It might be worth adding how typical this volume is of Friedlander’s work, which is unique among street photographers in that each volume offers a close examination of a single, often quite strange, theme. No one who has spent time with one Friedlander book would stumble upon another and not immediately know whose work it contained.