If you think you know what you are looking at, you are probably mistaken.

We have no idea how many images we look at every day. There are certainly hundreds. There may be thousands. We don’t know. We don’t count them. In a recent television commercial break of 3 minutes, I counted 95 screen changes. Each of them represented an image crafted to be understood at a level that requires a minimum of attention, thought, and involvement. When you consider that this example is repeated countless times in internet content, print ads, magazines, news stories, personal photographs, and everywhere else we consume pictures, it’s clear that we live with certain expectations about the way we think our photographs should look. We want them to be familiar in the context of our experience, fit neatly into tidy categories, and have a simple message, -so we can move on with our busy day.

In the nearly 200 years since Joseph Nicephorus Niépce was credited for taking the world’s first photograph, more gear got into the hands of more people, who made photographs of people, places, events, and things that were important to them. Technology progressed. Cameras got smaller and easier to use. Lenses got sharper. Films, and then sensors got better. Science, industry, journalism and the popular aesthetic would embrace the camera’s ability to see the world with indiscriminate objectivity and define photography’s purpose. Its role was to show us what was real. But usually, the last thing we want to see in a picture is something we have to think about.

The least understood genre in photography, and the one that demands the most thought is the abstraction. A common understanding of the abstract is imagery that cannot be identified. A pejorative description commonly used describes the genre using the term, “nonrepresentational”. It defines abstract photography in broad terms in the context of what it isn’t about. A better one is the often cited definition offered by the Tate Gallery which states: “Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect.” Given the rapid pace of a modern society where nuance is rare, judgments are made in terms of absolutes, and the audience for photography is dominated by documentarians and their biases, it is not surprising that we accept generalizations like these.

The last part of the 19th century, and the early 20th century saw incredible changes in science, technology, industry, transportation, communication, international trade, economics, politics, and social relationships. A better understanding of how everything worked, meant that just about all of the finite boundaries defining the real world were being crossed, and opened to new inquiry.

Painters responded by creating radically different expressions of light, color, space, time, geometry, form, motion, and other attributes of reality as it had newly been opened to explore.

Photography was too new to be accepted as a fine art. Its conventions were still being made up as it went along. So it was only natural for it to turn to painting as a guide to direct its subjects, themes and visual style. The documentarians who photographed battlefields of the Crimean War, the grandeur of the American West, and the conditions of life in New York’s tenements, were being joined by practitioners who saw that there was another creative avenue that they could travel by following the lead of the abstract painters.

Photography was less than 100 years old when the abstract art movement in Europe and America began. By comparison, Sandro Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus”, painted in 1484, was already more than 400 years old. Clearly there were differences in the maturity of process and materials respective to each of the disciplines. Nonetheless, segments of the early 20th century photographic community had hopes for the new technology to be accepted by the arts.

Most notable among early photographers was Alfred Stieglitz. His personal relationship with Georgia O’Keefe is the stuff of legend. He founded the Photo-Secession group whose purpose was to secede from the accepted idea of what constitutes a photograph. Another purpose was to promote photography as a fine art. He actively recruited fellow photographer, Edward Steichen, because of his credentials as a respected painter, as well. Steichen later used his connections to bring the work of Henri Matisse, Paul Cezanne, and Auguste Rodin to Stieglitz’s New York, Gallery 291. It isn’t a surprise then, that photographers would share some of the same aesthetics as painters, and work with the same sense of hope of validity, even if without the same quality of pedigree. However, is it appropriate to expect abstract photography to look like abstract paintings?

While photographers and painters may be kindred spirits, the pictures they produce are much different. Some of it is due to the significant differences in the way they approach their work. Some of it is because of their uniquely different technologies and materials.

To begin with, painting is a nonrepresentational process by nature. As much as a finished piece of work matters, it is a subjective expression of the painter’s interaction with the canvas. An extreme example is the abstract work of Jackson Pollock and the technique he used of pouring and dripping paint on canvas. It is an illustration of the way a painter can be actively involved with materials and process, and detached from direct engagement with a subject. Very few photographs can approach this level of abstraction beginning with a depiction of reality.

The cliché is to say that an artist starts with a blank canvas. And the truth in it is that from beginning to end, every step in the process is the result of conscious, deliberate and additive decisions. From the way paint is mixed by adding a bit of this color to a bit of that color, to the way that blocks of shapes and colors are added to a canvas, – to the way each line is added with an intentional stroke of a brush,- the painter chooses which details to include, how to construct the light,- and what the setting is to be. The painter can, in fact create an entire canvas from life, a preliminary sketch, or of details whose only reality exists in the imagination. It is a contemplative process that composites over the course of hours, months, or perhaps years. And the result can be highly realistic, or a complete fantasy, depending on the artist’s intent.

What makes an abstract photograph essentially different from a painting? Is it that the photographic process is representational by nature? The camera was invented to depict reality. A photograph is a visual document of the way light is reflected or transmitted onto a sensor or piece of film. It can be focused or uncontrolled by optics. A shutter can define it in a fraction of a moment, or the record of the passing of light over time. It can be expressed in any number of ways. But it will always be essentially some representation of the way that light makes a drawing of something that is real.

It is indiscriminate in what it reveals. We may choose to compose a scene in one way or another. We may decide on a panoramic aspect ratio instead of a square. We may additionally crop to clarify a narrative. But our sensors and lenses capture at once, every detail in an exposure. There is an immediacy to the process which doesn’t allow us to build a composition by selectively adding the elements we want to include, and ignore the ones that may be distracting. The popularity of digital processing is changing some of this in the way it permits us to subtract details. Nonetheless, we always begin with something that exists. And the images we make are the direct result of addressing that reality.

The dilemma we face is that photography has chosen painting as its bedfellow, and accepted its standards and expectations for abstraction, while they are fundamentally different disciplines in every way.

Over the years, photographers have exploited technology that the general public wasn’t familiar with yet, to do what painters do. Man Ray’s work with photograms is the first example that comes to mind. Aerial photography produced some interesting macro abstractions when flight was in its early days. X-Ray exposures became popular. More contemporary examples are images made with the Hubble Telescope, or those of the Covid-19 virus made with a microscope. But long after we became familiar with these techniques, they are no longer considered nonrepresentational, though their appeal remains and are still considered abstractions.

Suppose that rather than conceding that photography is deficient in meeting the criteria of abstraction, it is the accepted definitions that are deficient. Is an image required to be completely unidentifiable to be considered abstract? Some have suggested that there is a scale of abstraction that can be considered to recognize images that are representational, yet have some varying elements of abstraction. An example that most of us are familiar with is Edward Weston’s “Pepper No. 30”. There is no question about what we are looking at. Weston was a member of the f64 group, which emphasized unqualified objectivity in photography. Yet for whatever relevance its visual appeal has based on the subject’s functional identity, we react to the qualities of light and shadow, sense of motion, lines and shapes, and the suggestion of human form and sensuality.

These elements are examples of some of the abstract qualities that exist in images whether they are representational or not.

In another example from Weston, consider “Nude (Charis in Doorway, Santa Monica, 1936)”. Here, Weston’s muse, Charis Wilson, is photographed in an open doorway,- bathed in brilliant light, and wound up like a ball of rubber bands in a tangle of limbs. Again, there is nothing nonrepresentational about the picture. The appeal is less about the surface identity of the subject as a naked woman than the way the composition creates a sense of rolling motion, and the quality of light transcends the figure into a study in lines, and shadows.

Weston understood human nature. He knew that we see what we expect to see in a photograph, and miss others based on our conditioning. Weston was concerned that postal inspectors would see his work, simply for its surface appearance, and not understand it the way it was intended. In a memory shared about the image, Wilson recalled Weston stressing over whether a few visible pubic hairs would prevent shipping a print by the U.S. Mail. What we see in these examples is that qualities like light, shadow, space, time, motion, geometry, lines, shapes, patterns, sensuality, joy, sadness, and any number of real and meaningful abstract visual aspects can exist in a photograph whether it is representational, or not. It is conceivable that a completely nonrepresentational image could exist without expressing any abstract qualities. More likely, every image expresses some of them, and is in some way abstract.

In painting, we identify nonrepresentational images as abstract because the process is nonrepresentational by nature, and any example, regardless of how well done it might be will be less photorealistic than anything a camera can produce. Our way of thinking in terms of absolutes, requires extreme expression to tell it apart from attempts at realism. We identify abstract photography the same way precisely for the opposite reason. It is objective by nature, and needs extreme examples for us to see it where we don’t expect to find it. The deficiency is in the way we have been conditioned to look, and see.

The way that I would define the abstract in photography is, an image which may be representational- or not,- whose appeal relies on, but is not required to be entirely dependent upon some assortment of shapes, patterns, lines, colors, forms, texture, space, concept or other quality, that is unrelated to the apparent subject’s innate identity, to achieve its effect.

I think that what we get wrong is accepting the notion that abstraction and representational expressions must be mutually exclusive. While we like to organize everything in terms of absolutes, we misclassify work according to our expectation biases when it exhibits attributes of more than one genre. We are coming to acknowledge that there are cases in a messy gray area that defy easy categorization. We can invent an infinite number of new folders to file the endless combinations of genre influences. Or we can simply accept that an image may fully meet the criteria of several genres at the same time.

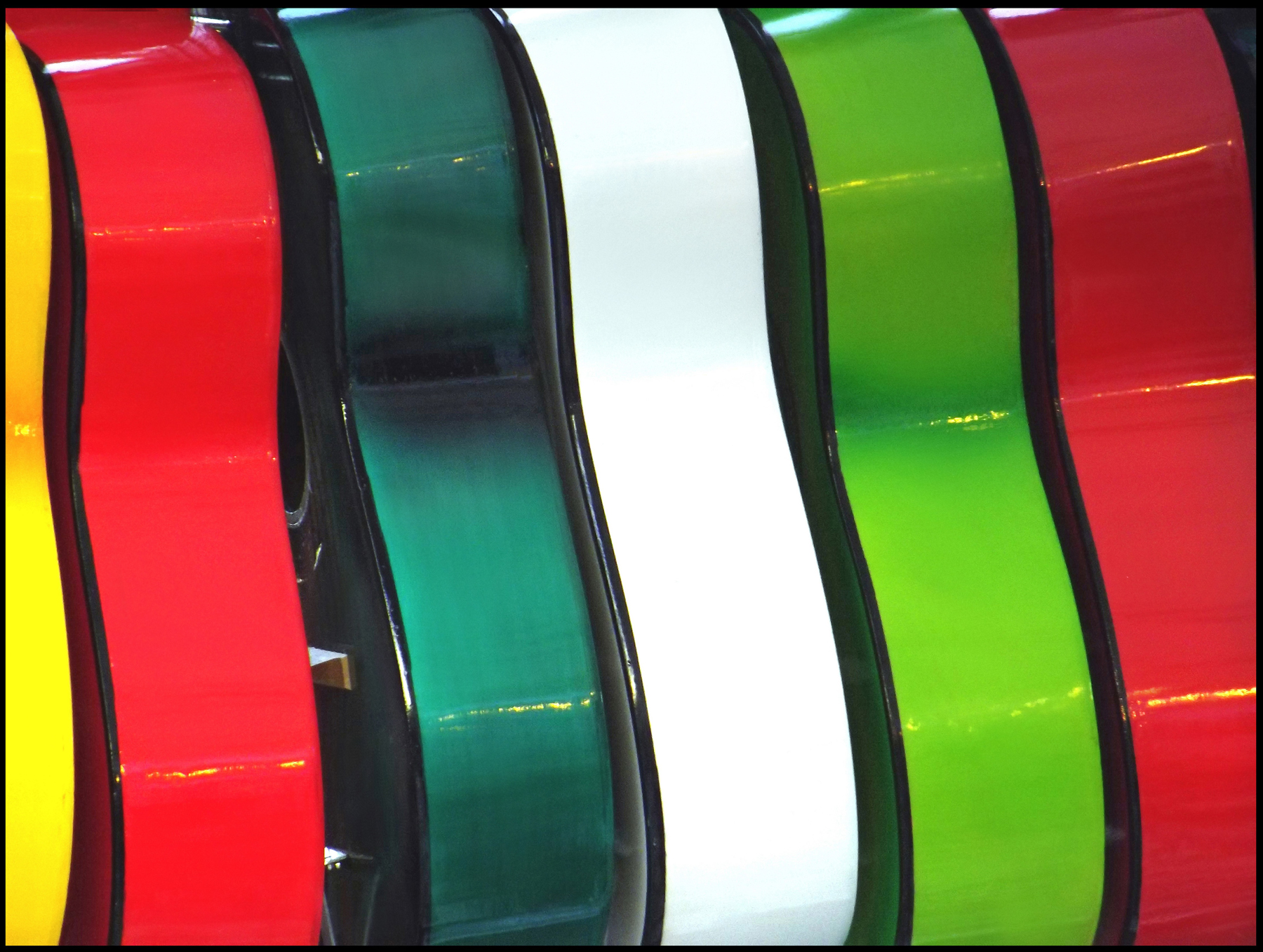

However we wrap our brains around it, the tragedy of perception that we face is that once we think we know what we see, we stop looking at it. If we don’t see qualities of the abstract in the most representational images, is it that we are simply looking at them too literally, – and too shallowly? In my own work, I choose subjects that are familiar to everyone. There is nothing remarkable about them for their functional identity. The images I make are less about the subjects as we know them, but more about abstract qualities like color, lines, shapes, patterns, space, texture and emotion that define them with the same full validity as any that do not present representational context to remind us that abstraction is real. I would invite my fellow image makers to look at what we see with fresh eyes. Are we letting our expectations of what we want to see get in the way of seeing everything that is really there? Are we passing up something that is visually exciting because we are looking at situations too literally, and missing complexity that is dismissed because of our social conditioning? It only takes a bit of conscious thought about the way we work, what it is that excites us about what we see, and keeping an open eye and mind.

FRANK STYBURSKI photographs abstract patterns, shapes, and reflections found in everyday things. He lives in Chicago, where he worked at commercial labs and supply sources for forty years before assembling a fine art portfolio.He is a past Board Member of Northwest Arts Connection,- an advocacy group dedicated to presenting art with connections to the community, on Chicago’s northwest side.

He established the Shot of Art series of art exhibits at PERKOLATOR, in the Irving-Austin Business District of Chicago, and served as its original curator.

He shows his work in galleries and nontraditional exhibit spaces, where people gather to work, play, and do business. He has participated in numerous group and solo shows in collaboration with community groups, arts advocacy organizations and small businesses. His work has been on display at the Polish Museum of America, the Illinois State Museum in Lockport, and Harold Washington Library Center.

Ted

January 16, 2022 at 20:33

I find that many viewers don’t realize that it is acceptable to admire geometry, the curve of a line, a splash of color, repetition, etc. Most seem to rely upon photography as a documentary discipline, and expect to be shown a picture of something. When they are confronted with an abstraction, they think it is necessary for them to discover the hidden picture within the image, as if it were a game between the spectator and the photographer.

Frank Styburski

January 17, 2022 at 15:13

Thanks, Ted.

It seems to me that all of those qualities that you mention like geometry and the curve of a line have value for their intrinsic beauty, and the way that they make us feel. For me, they are just as much an integral part of an image’s reality as the things, events, and people we photograph for other reasons.

Sadly, I think that they get dismissed by some of our friends. It’s easy to understand. We live in a fast-paced world where we need to identify what we see quickly, and move on.

Glad that you like the article, and that we share an appreciation for some of the broader aspects packed into our images.

Scott

January 16, 2022 at 21:05

Frank,

That’s a wonderful essay. Thanks. I wonder if you might elaborate upon the notion that “non-representational” is “pejorative.” The other day I was using that term in a discussion we were having and I really don’t think of “non-representational” as having a negative connotation; for me me, it’s merely the opposite of “representational.”

Ted

January 17, 2022 at 08:36

I use the term “non-representational” in my photography lectures all the time. Nothing negative intended.

Frank Styburski

January 17, 2022 at 15:58

Thanks, Ted.

I just responded to Scott’s comment.

I think it has some relevance to yours as well.

All the best,

Frank

Frank Styburski

January 17, 2022 at 15:55

Thank you, Scott.

I think that the issue that I have with the term, “non-representational” is that it defines the abstract in broad terms, in the context of what it isn’t.

Documentary photographers, who pretty much dominate our community, would say that the camera was invented to depict reality, and that depiction is representational. The suggestion is that the abstract either isn’t important, – or doesn’t exist at all.

It is either a misunderstanding of abstraction, or a value based dismissal.

My position is that abstract qualities are real, and probably present, in varying degrees, in all images.

The unfortunate thing is that if we accept the term, we are buying into an unsympathetic narrative that influences the way we see abstraction and the way we express it in our own work.

Thanks for your thoughts, Scott! I hope that I’ve clarified my position. It’s always great to exchange ideas in conversations like theses.

Scott

January 19, 2022 at 00:54

I see your point and I agree that, yes, the abstract is real. I’m still hung up on something though. I guess most of my work is “anti-“ representation; that is, I will hardly ever take a photo of a dog or a cat or a house or a tree, etc.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

January 24, 2022 at 08:33

I agree with Scott. Pejorative and Non-Representational, to me, are nowhere close to the same thing. Non-representational is mainly used for painting more than photos. And even there, where it fits better, I do not consider it pejorative. For me, Frank, what you call abstract in some of the examples shown is clearly not what I consider such. I see the item and can define it clearly. That, to me, is not an abstraction. I could go on and detail each example, but why? Let’s just say that for me, this article did not hit the mark on defining true photographic abstraction in the least.

Scott Bentley

January 24, 2022 at 09:52

Yes, Diana, I’d agree that true abstract works are more obviously non-representational. Thanks for making this point.

Frank Styburski

January 24, 2022 at 15:51

Thanks for your thoughts, Diana.

I understand that there is a diversity of opinion on the matter.

I don’t expect everyone to be persuaded to my way of thinking. I am pleased that the article may have made you reconsider the definitions, criteria, and aesthetics we use when we make and evaluate images.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

January 24, 2022 at 18:30

Frank, perhaps I did not state that directly, but it did not make me reconsider. Best, diana

Frank Styburski

January 24, 2022 at 19:16

Thanks for the clarification, Diana.

It shows you have confidence in your positions.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

January 24, 2022 at 19:23

Frank, why would I be any less confident in my positions on art topics than you are on your own. That was quite a patronizing, bordering on sexist, comment. You lost this reader right there.

Frank Styburski

January 24, 2022 at 19:34

No offense was intended.

Frank Styburski

January 24, 2022 at 20:40

The internet isn’t very good at conveying nuance. So intent can get missed.

I know a lot of artists. Some of them are photographers, and some are practitioners in other media. Speaking of my own experience, and my experience with others, confidence of voice, aesthetics, and definitions is not something that always comes easily. Sometimes not at all. Lack of it doesn’t mean that the art being made doesn’t have merit.

But confidence can often result in stronger visual statements.

The downside is that with deeper conviction, our work may meet with deeper appeal and disapproval. And the positions we hold become more debatable as they become more finely tuned.

While we may disagree in our positions, my comment was intended as an acknowledgment of someone who knows her own voice, and the place where her visual strength originates.

I hope to have more conversations with you in the days to come.

Nazmul Bashar

January 17, 2022 at 07:54

Well researched essay on a very debated segment of photography. My main take away from the reading is abstraction in photography “Depend(s) upon some assortment of shapes, patterns, lines, colors, forms, texture, space, concept or other quality, that is unrelated to the apparent subject’s innate identity, to achieve its effect.” My question is, does it have to be unrelated to the ‘subject’s innate identity’?

Frank Styburski

January 17, 2022 at 17:49

Thank you for the compliment, Nazmul!

And thank you for the question, as well.

I think that we make things, and find things in nature that are identified by their function, or other objective relationships. We all know what a chair is.

But it can take many forms. It is rarely defined by the form it takes. And it is in the form, (and other qualities), rather than function that we find the abstraction.

I’ve been pondering your question for a while now. I can’t think of any exceptions. Do you have any specific suggestions?

I welcome dialog of this kind.

All the best,

Frank

Scott

January 19, 2022 at 01:03

I see your point and I agree that, yes, the abstract is real. I’m still hung up on something though. I guess most of my work is “anti-“ representation; that is, I will hardly ever take a photo of a dog or a cat or a house or a tree, etc.

I think we may have a basic discussion of the tension between form and content with your twist, Frank, that form IS content.

Frank Styburski

January 19, 2022 at 01:20

I think that the images you make, Scott, are representational. They emphasize aspects that most documentary photographers dismiss, while leaving out some of the bits they show. I don’t believe that we can be completely objective in the pictures we make. And there is no obligation to “document” every bit of reality in the situations we photograph. If we did that, it would confuse the visual statements we make.

Nazmul Bashar

January 17, 2022 at 20:31

Last year I was benefitted watching this long You Tube video from David Brommer. He says art and photography are inseparable. You may like this discussion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TPkEiwLybzE

Frank Styburski

January 17, 2022 at 22:37

Thanks, Nazmul.

I’ve been doing business with B&H for a long time.

Their videos are usually informative.

I’ll give it a look.

Susy Kamber

January 18, 2022 at 01:48

I found your writing speaks messages, ones that draw upon knowledge and research. As a photographer and artist I continue to blend both genres together, each addresses questions and learning techniques. I like to overlap the answers and what happen when art meets photography. Thank you for writing on this subject!

Frank Styburski

January 18, 2022 at 15:18

Thanks for the compliment, Susy.

I agree that photography is best when it is practiced out of isolation, and with an awareness of the other arts. I think that practitioners from various disciplines can learn from each other. And the influence we exercise on each other can be a positive one.

Glad you like the article, Susy.

Glad that you shared your insights with us.

Frank

Scott

January 19, 2022 at 01:08

I think we basically have here a classic debate between form and content with your twist, Frank, that form IS content. I absolutely agree.

Frank Styburski

January 19, 2022 at 01:24

I would agree that we see eye to eye, here.

Thanks, Scott.

Chuck

February 8, 2022 at 19:03

This really hit home for me. I have been doing mostly abstractish photography for the past year now, first mostly in the vein of Aaron Siskind, but expanding beyond that as well. I was stuck in the painterly definition for a good number of months and then realized that, like you, that was an artificially restrictive box. Thanks for this.

Frank Styburski

February 9, 2022 at 15:56

Thank you, Chuck.

I think that photography, as an art form, has finally achieved enough security in its own skin to control its definitions, in its own terms.

I’m glad that the article was helpful.

Always pleased to make a positive connection with kindred spirit behind the lens.

Ramsay Bell Breslin

December 29, 2023 at 16:41

I enjoyed reading your article, Frank, and was especially drawn to the photograph “Balcony Abstraction,” in part because it illustrates my feeling that abstraction is to representation what shadows are to light. Shadows give shape, form, substance, and depth to light the way abstractions give shape, form, structure, and depth to representations. Your point that abstractions are no less ‘real’ than representations is an important one. However, for me the co-existence of abstraction and representation is as native to painting and drawing as it is to photography. In my experience, the difference between digital photography and painting is materiality. Digital photography is a dematerialized medium. I wholeheartedly agree that our understanding of abstraction in photographs draws from our knowledge and understanding of abstraction in painting and drawing and sculpture. As a result, photographic ideas established by abstract expressionist painters, say, often feel like retreads. To me, however, photography at its best has the power to enact perception in its purest form, as an idea that inspires thought and action. To be inspired is to breathe new life into actualities.