“Your right eye will always see a slightly different version of the truth to your left eye”

Dr. BRIAN MAY

Fifteen years ago I was wandering around a car-boot sale in a field in Surrey, England. A man was sitting on the edge of his bumper, selling vintage photographs and postcards out of shoeboxes on a folding card-table. It was where I bought my first stereoviews; I knew what they were, and what they were meant to do, but I did not have a Stereoscope of my own or had ever looked through one, I just loved the cards as facinating objects. I left with a lighter wallet, and five stereoviews in my bag showing views of the Boer War. Fast forward a few years and I am at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, looking for the first time at stereoviews as they were meant to be seen, through an object that looks like a cross between a plague doctor mask and some binoculars. The results were stunning, a level of clarity and perception more immersive than even the best prints from a large format camera. It was at this point the seeds of my new obsession were sown.

If you are feeling confused, then let me explain for you. A stereoview is the result of an idea dating back to 1838, and the work of inventor Charles Wheatstone. It is two photographs taken side by side, viewed together through a stereoscope. Your left eye is only able to see the left hand image, your right eye the right hand image. This tricks your brain into seeing them as one, and perceive infinite levels of depth. The way it works is like so; hold a finger up in front of your face, close one eye and look at it, switch to the other eye and repeat rapidly. The reason we see the finger jump in our view is due to our depth perception.

The technology has come and gone in fashion over the years but has never overtaken two dimensional photography due to always needing additional apparatus – a stereoscopic viewer, red and blue glasses in the 1950s and 1980s (anaglyph), a Viewmaster and cardboard disks of photos during our childhood, and latest of all, VR headsets or 3D glasses at the cinema. It is possible with practice to be able to “free-view”, that is to let your eyes blend the two images without a viewer but some are easier than others. But the only technique in 3D photography that does not need you to hold or wear special tools is the lenticular image, which you wiggle side to side (think gift shop postcards and bookmarks); but these are less successful to look at, and horrendously expensive compared to other types to produce. For your ease in this article I am showing the examples as both stereoviews, and lenticular animations.

It was not until 2017 I launched myself into becoming a stereoscopic photographer. Inspired by one of the earliest known names in the field: T.R. Williams and his series ‘Scenes in Our Village’ consisted of forty-nine compositions. Williams is largely unknown in the history of photography, which is an immense shame. Scenes in our Village is a project that in 1855 is one of the earliest examples of a photographer taking a social-political standpoint in regards to our use of the environment and the impact of coming industrial innovation. Based on Williams, I created a series of forty-nine views documenting the communities that use the 2000 miles of British canal network.

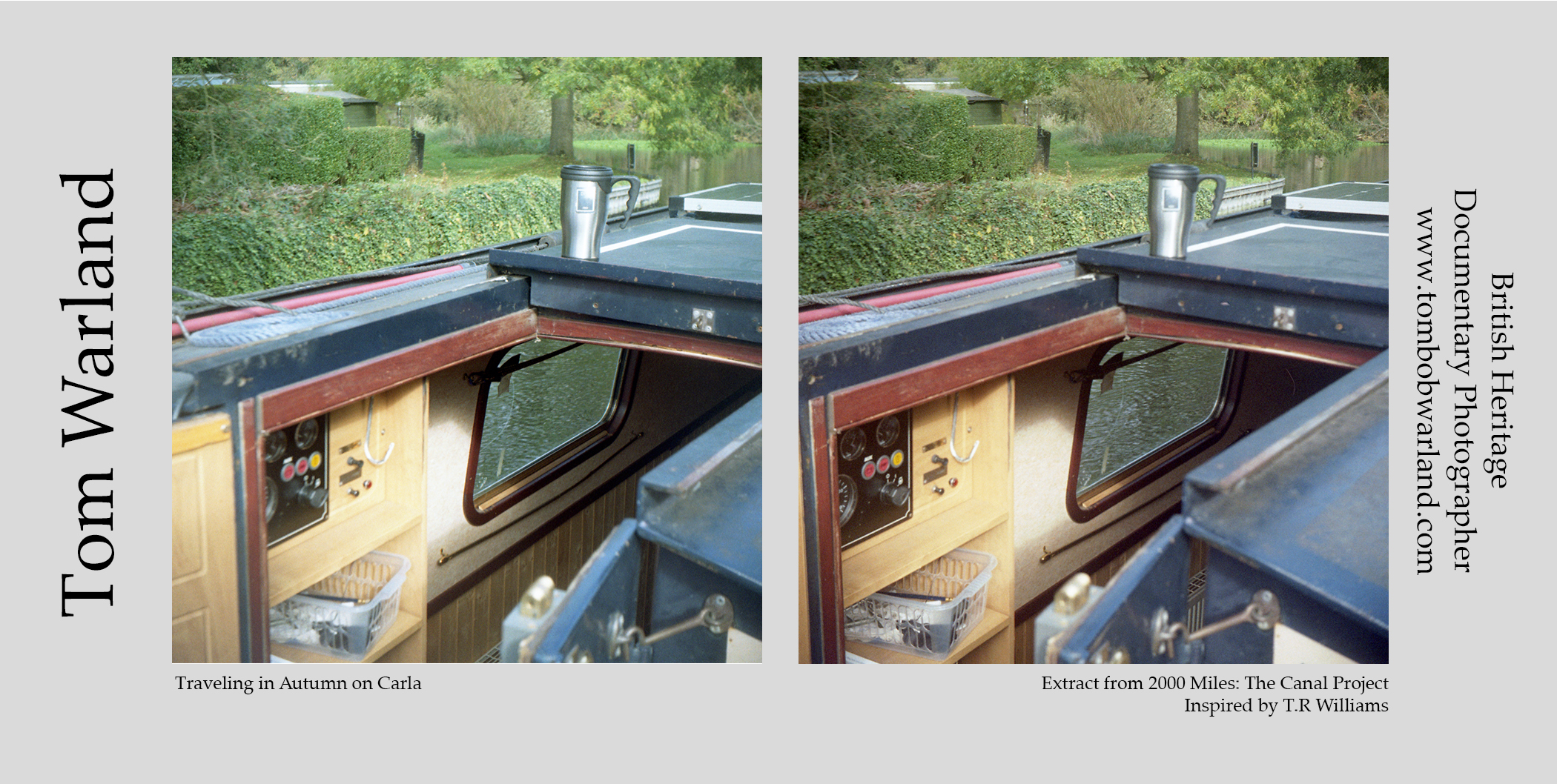

At this point, I thought I was just fulfilling a personal curiosity whilst I travelled around the area’s canals easily accessible from where I was living, making portraits of boat owners and fisherman, and the canal within its changing landscape. I did not realise it would grew to become a key part of my practice. I convinced a boat owner called Baz to let me and my wife join him for a day as he travelled along the waterways onboard Carla. This gave me the opportunity to photograph from a very different perspective. To not be an outsider looking into a situation, but to be part of that experience. It is in this that I think I found the real joy of stereoscopy; because looking at 3D photographs is immersive (as anyone who has tried a VR headset will agree), to photograph onboard the boats, showing that life from inside and then experience them in three dimensions allowed a sense of reality to the viewers that they would probably get to see for themselves.

From here we went further and hired a boat for a week. My daughter was now about eight months old, it was mid-October and a storm was hitting Britain with some of the strongest winds in years. Not the best day to pick up a boat and attempt to reach Oxford (spoiler: we never made it anywhere near as far). After being shown the technical stuff on the boat for our journey by the owner, we set off, my wife and daughter nice and cosy inside reading books, me wondering if my photographic obsession was now out of hand. We gave up after about an hour and moored up for the rest of that afternoon and hoped the ropes would not come untied in the night.

The following day, after some early morning stereoviews and a bacon sandwich, we set off, grateful the winds had subsided. Then just before lunchtime we had engine problems. Investigating I found that a net used as a temporary bankside repair, had come tangled around the propeller. I am now hanging off the back of the boat with my arm submerged in dark freezing cold water trying to saw through the netting with a bread-knife, whilst wishing it was someone else with the task, so I could be photographing all of this. It was at this point I discovered one of the most wonderful elements of the canal community – the Waterways Chaplaincy. A series of floating churches that move around the network for boaters to join for services on their travels. Now I am not a religious man, but I was grateful for this chaplain Tim, and his help as he leapt onboard, took out a penknife and helped me clear the netting. He then agreed to stand for a portrait alongside his co-worker and dog; I’m grateful that I met them, and that I was able to include their supportive nature within the work.

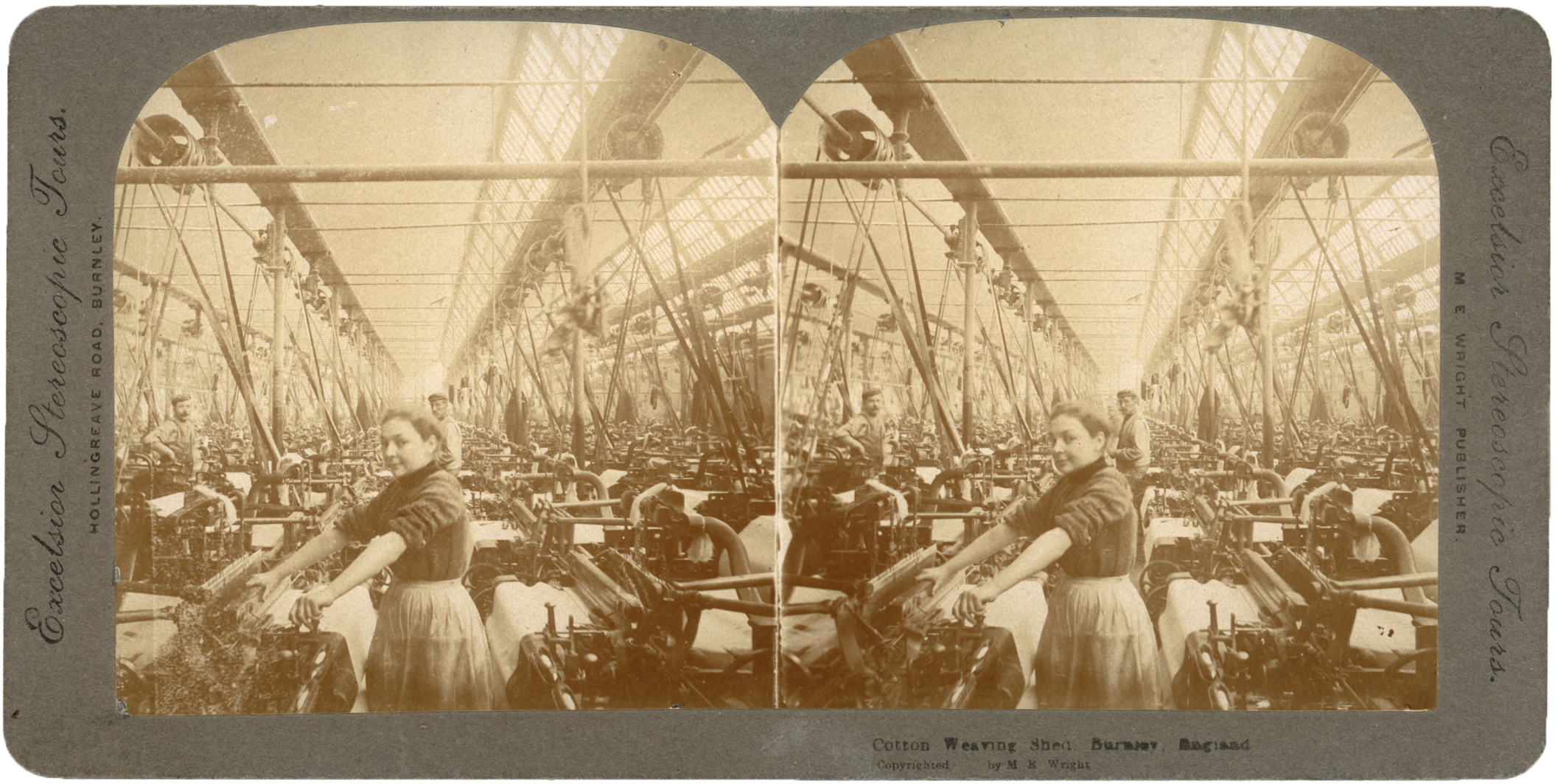

Stereoscopy is an excellent practical teacher. When we learn as photographers, composition is often explained as a flat concept of left and right, up and down as we walk about the rule of thirds, symmetry, or leading lines. In regards to a stereo image, this level of composition is incredibly passive. I learnt it is better to think of composition as being based on: back, middle and front such as this example “Cotton Weaving Shed, Burnley England” by M. E. Wright which gives greater depth and builds a sense of scale. This reminded me of my very first experience of using a camera; I was about 6 years old, looking through my Dad’s Yashica at a ruined church; I remember him saying, ”Look at the rock at the front of the path, have that in the foreground, then use the path to follow up to the church”. It has helped me remember this early compositional advice, and to build this more into all my photography, to create as dynamic a composition as I always can.

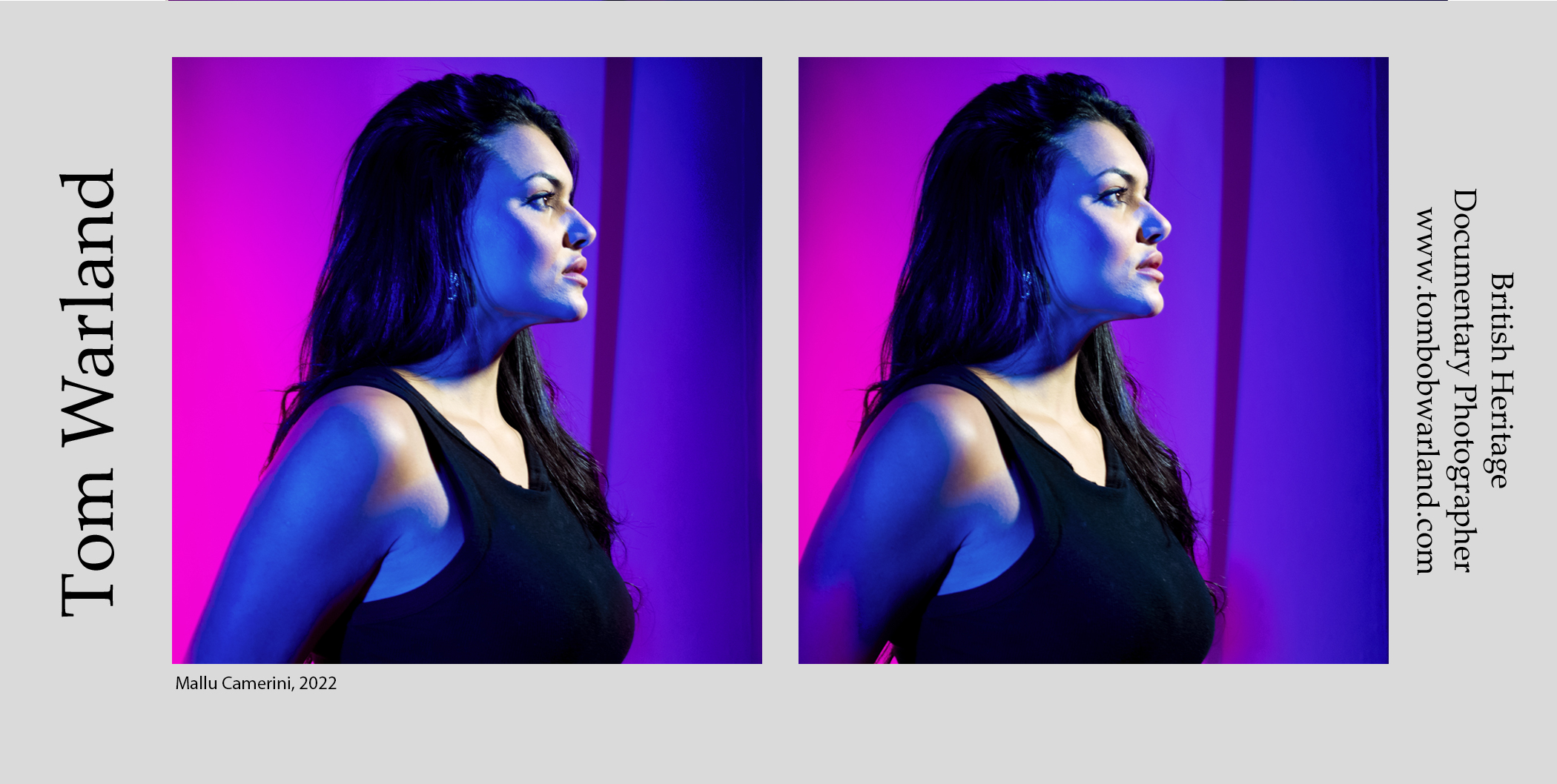

My examples I have shown were shot using a Wray Stereographic 35mm camera, though some were also created sequentially with normal cameras, photographing individually the left and right image; I’m now exploring the use of stereo work both for street photography, and also in studio portraiture.

If I have tempted your curiosity with stereoscopy, there is a wealth of resources and information available, phone apps for producing sequential stereoviews, books and also magazines. The starting point I would recommend is the revived London Stereoscopic Company; which is a great source of information online and books, as well as making stereoview reproductions, they also make their own range of affordable viewers called Owls and these work with all vintage and most modern stereoviews. You can find them at www.londonstereo.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Warland is a visual anthropologist specialising in the use of Documentary Photography , Film, and illustration; and also a lecturer at Buckinghamshire College Group living and working in London and the surrounding area. Since graduating from the University of Wales; Newport’s Documentary Photography course he has explored traditional and largely forgotten ideas in British society and culture, and has work featured in various publications and exhibited nationally.

Tom also works as a commercial and events photographer documenting through the use of photography and film; music festivals as well working for musical groups such as Breabach, Steve Knightley, Phil Beer, The Selecter and has also made music videos for bands including The Nameless Three.

Tom has recently completed the MA Photojournalism & Documentary Photography course at UAL: London College of Communication, and a course in anthropology at the University of Queensland, Australia.

Cary Wasserman

December 13, 2022 at 17:02

A longtime stereo practitioner myself, and once found on a dusty bookshelf a neglected two volume set of Egypt and Italy. Investigation revealed they were really boxes of Underwood & Underwood stereo photos in perfect condition, greatly undervalued as unwanted travel books.

The gif solution seems particularly appropriate for depicting the storm you describe. For portraits, and not evident in the original stereo image, perhaps for something more like a touch of Parkinson’s Syndrome?