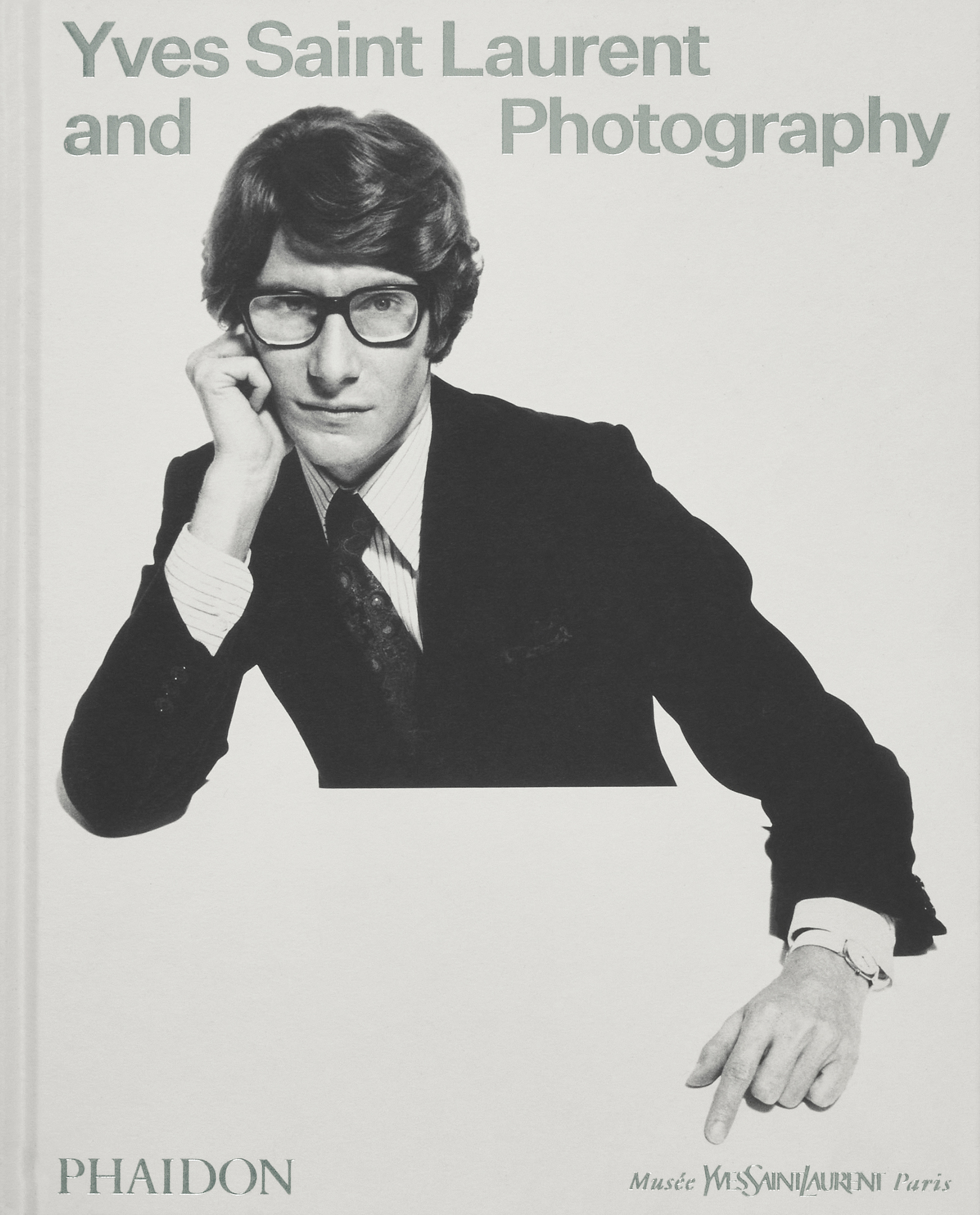

There are moments when photography exceeds its brief, when it does not simply record reality, but like a breath, a puff of air, catches something ephemeral and renders it eternal. Yves Saint Laurent understood this. He knew that fashion, like photography, is all about looking, lighting, framing. This book, published to coincide with the exhibition held as part of the Arles Photography Festival, explores the intimate relationship between the couturier and the medium of photography.

Christopher Wiesner, Director

Arles Photography Festival

“Yves Saint Laurent and Photography, edited by Elsa Janssen

Published by Phaidon Press, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

I will admit, and this will come as a surprise to no one, I do not follow fashion. I can tell you the names of designers who are popular, some of them, but the trends, styles, and issues of high fashion rarely make the top of my interest list. Perhaps this shows in my outfits.

Nonetheless, I have on my desk today a book I find mesmerizing and wonderful. Yves Saint Laurent and Photography, published by Phaidon Press, is an extraordinary anthology of images revolving around the YSL fashion house, but the book is decidedly and successfully focused on photography.

© The Irving Penn Foundation / © Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent (page 21)

Yves Saint Laurent, I have learned, had a particularly insightful and dynamic relationship with a whole world of photographers of varying styles, which went a long way towards keeping his brand present in popular imagination, present in the avant-garde, and as a way for both the designer and the photographers to see new creative potentials.

It is odd how a photo book can change the timing, the cadence of a day. It can slow down or speed up an afternoon, or longer, as you find yourself examining the images both for their aesthetic effect and then, working backwards, unpacking their technical sophistication, their place in a timeline, and more. Even though I am not particularly interested in fashion, I find myself deeply interested in this book, and the book rewards that interest.

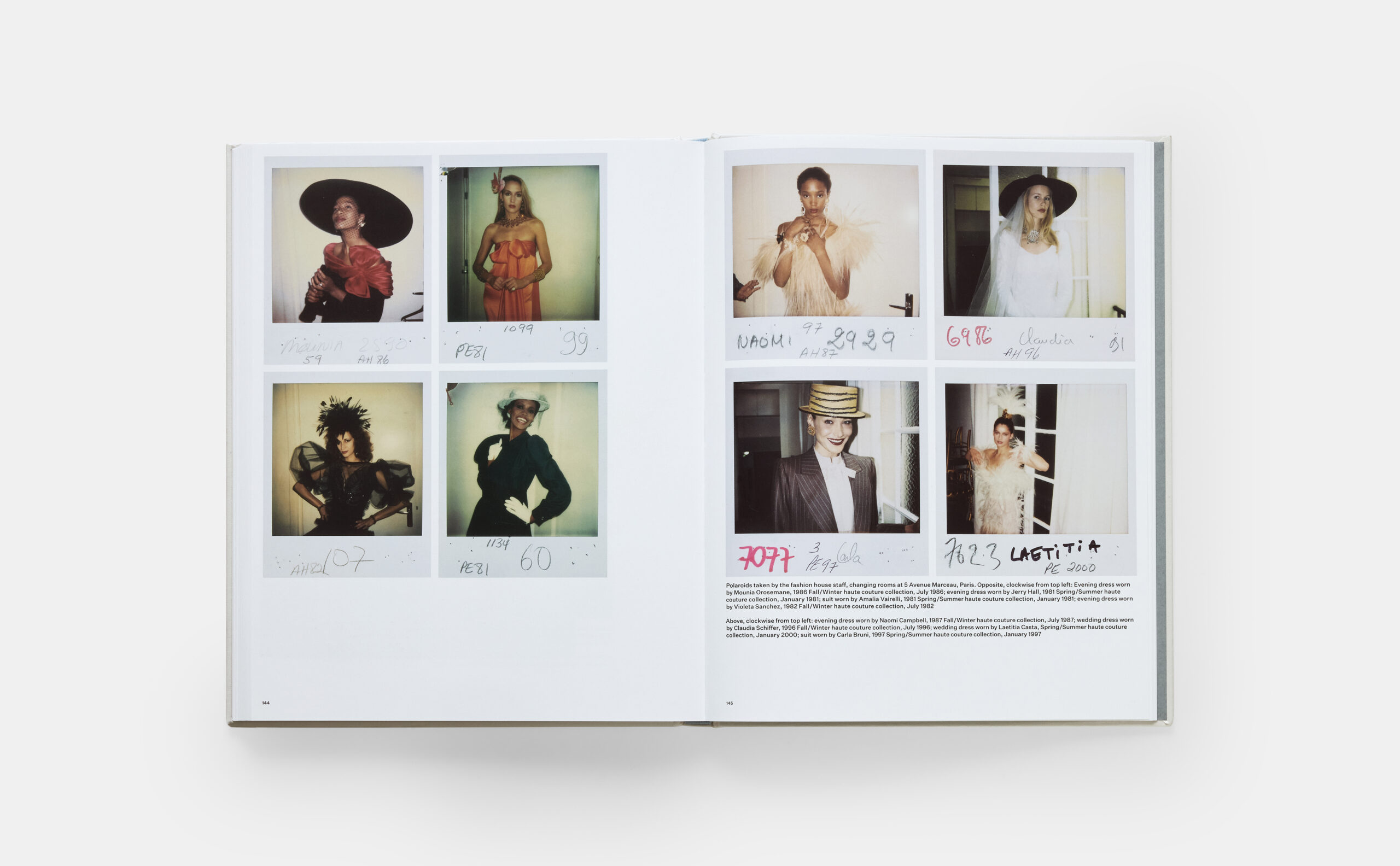

© Yves Saint Laurent / © Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent. (page 144, bottom left)

While the photography is, of course, wonderful, one of the real merits of this book is the text that comes along with it. For example, Christoph Wiesner, Director of the Arles Photography Festival, offers these insights:

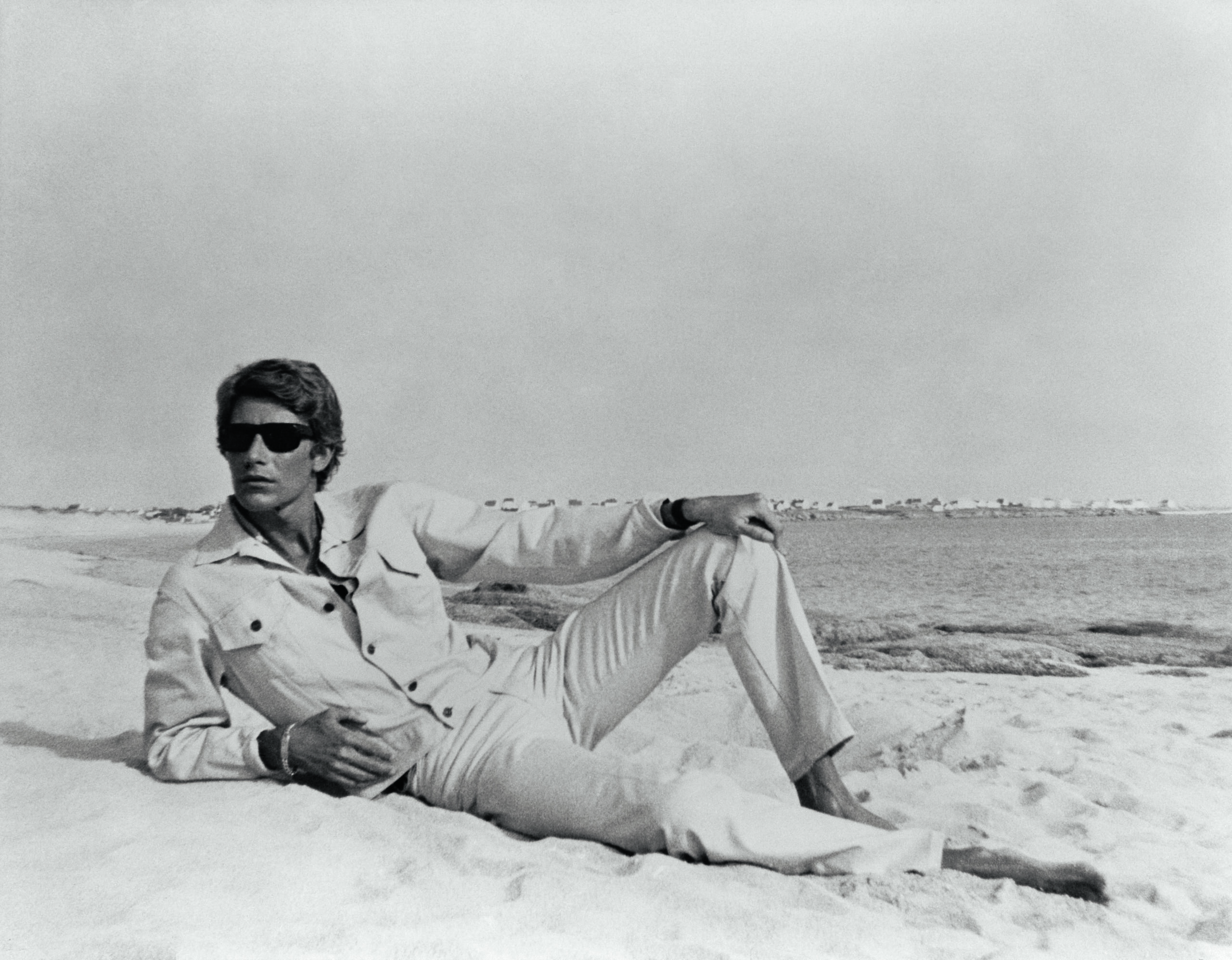

Irving Penn’s treatment of Saint Laurent is radically minimalistic, allowing for a picture of the man to emerge. The restrained framing, rigorous use of black and white, and dense play of light and shade reveal a quiet vulnerability. It is not just the couturier who is being photographed, but the inner man, with his doubts and silences, his subtly melancholic gaze.

Later in that same essay, we read:

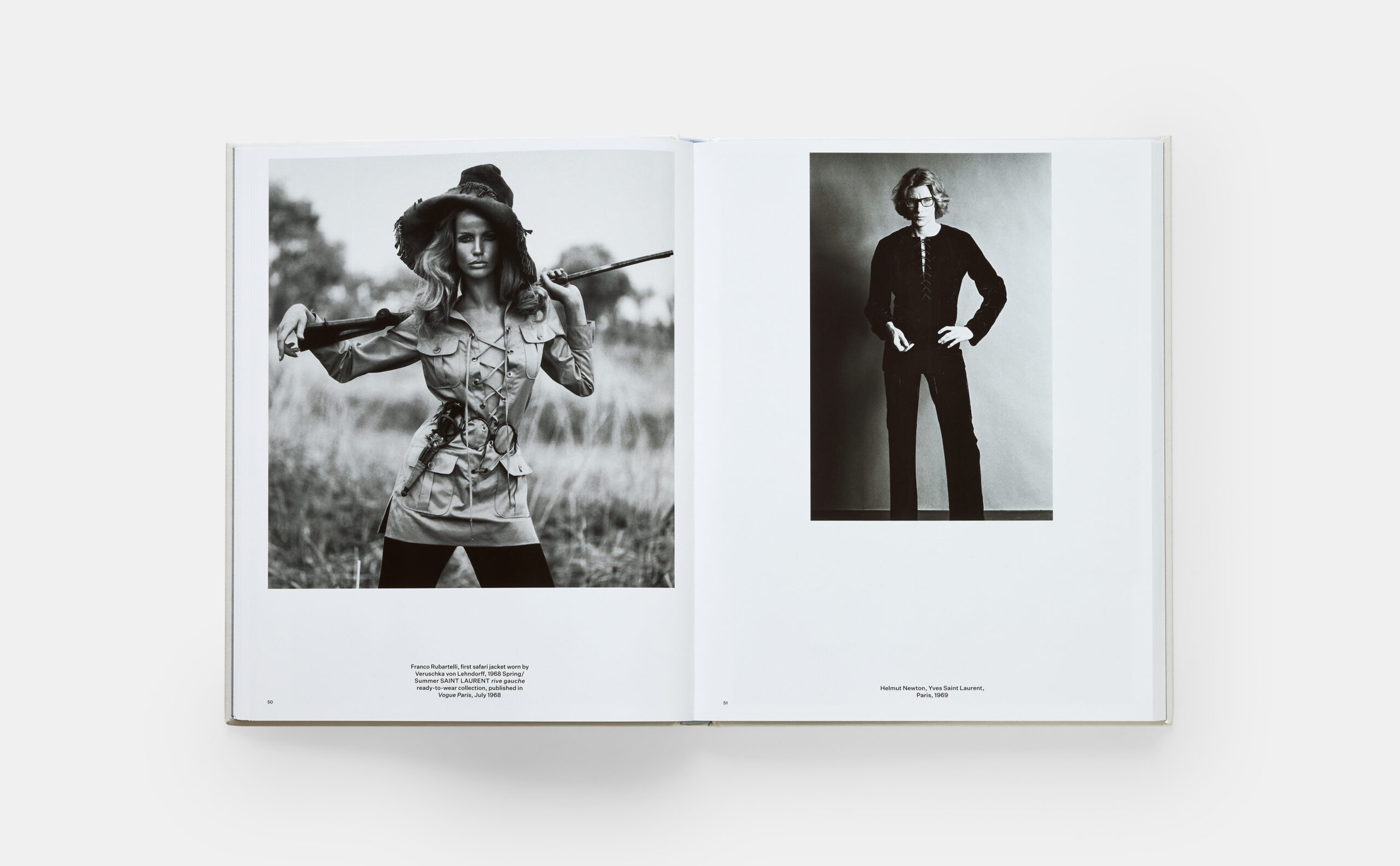

Photographed by William Klein, notably in his experimental series of fashion pictures incorporating “light painting,” Saint Laurent’s iconic women’s suit, worn by Dorothy McGowan, became a burst of pure freedom. Strictly perfect in its architectural construction, the suit is run through with piercing trails of shifting light, setting up a tension between structure and chaos. Klein does not photograph fashion: he makes it vibrate, electrifies it and propels it into a space where anything is possible.

This is a book about photography with the fashion icon almost serving as example more than subject.

In an introduction by Elsa Jansen, I learn:

These pictures are a reminder of just how adventurous the fashion magazines of the period were and how ahead of their times figures, such as Alexander Lieberman, were. As artistic director of American Vogue from 1942 to 1962, then editorial director of Conde Nast Publications until 1990, Lieberman knew how to gather talents from all backgrounds. Each of the photographers who were commissioned saw fashion in their own particular way. William Klein, for example, was not especially interested in it, but took the opportunity it presented to pursue his own technical and artistic experiments. For Irving Penn, it was about selling a dream, not clothes, and his aim was to dazzle people with his images, while Helmut Newton saw himself as a “minion” in the service of whatever he was photographing.

© Yves Saint Laurent / © Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent. (page 144, bottom right)

The text in this book is a wonderful discourse on fashion photography in the 20th Century, and, tellingly, throughout the book, the captions of the great many captivating images of various outfits, models, and settings begin with the photographer’s name, then the model’s name, then its placement in what season and line of fashion or where it was published.

The emphasis throughout the book is on the photography within both the unified and tremendously varied subject of fashion. Turning every page seems to reveal a new interpretation of the genre. Turning every page is exciting.

Covering YSL from the 1950s up to the more recent, this book sparks all sorts of memories and imagination. As I turn the pages, I find myself remembering many of the photographs. Although I don’t remember when I saw them or what magazine held the images, the pictures still found a place in a persistent memory. Turning the pages, I also find myself deeply impressed again by stuff I’m familiar with—Horst P. Horst’s lighting, Helmut Newton’s composition, Irving Penn’s drama, Annie Leibovitz’s group portraits, etc.

Someone who is interested in fashion will see this as a compelling history book, with a unifying theme of photography. Somebody who’s interested in photography will see this as a compelling history book, with the unifying theme of fashion. Someone who is interested in both will find it difficult to put this book back on the coffee table.

With forewords by Madison Cox and Christoph Wiesner, and texts by Elsa Janssen, Simon Baker, Serena Bucalo-Mussely, Alice Morin, and Clémentine Cuinet. Photos: © Franco Rubartelli. By kind permission of Ira Stehmann Fine Art, Munich

(left) © Helmut Newton Foundation/Trunk Archive (right) © Yves Saint Laurent © Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

Photos: © Yves Saint Laurent © Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

While at first, I was surprised by how much of this work is in black and white. It didn’t take very long for me to see that the first image here (after the introductory work) is from 1955: Richard Avedon’s Dovima with Elephants. As color comes into the photographic world, it comes into the book, while black and white remains as well.

There is a kind of fashion photography that goes well beyond images for a mail-order catalog. It can reveal a bit about the heart, soul, and culture of the time as much as street photography or anything else. Even though it’s most often highly constructed, posed, and lit, it still speaks to something about character. Whether I’m looking at a William Klein image of models backstage at a fashion show or a Jeanloup Sieff image of a model in a black dress with a hoop and stick, this book creates the kind of intimacy and curiosity that rewards every moment spent pausing, turning a page, and pausing again.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.