Many years ago, I stumbled across a series of articles in The Guardian that caught my eye. The series was called My Best Shot and featured photographers talking about exactly what the title suggests – their best photograph. The series is still going strong and features precisely what you would expect from that particular newspaper’s art content: brilliance, hilarity, creativity, history, weirdness, cutting edge documentary work, and, occasionally, the odd bit of pretentious nonsense.

Thankfully, the feature’s wonderful far outweighs the dreadful. In fact, it has previously carried work from photographers whom I have featured in this column: Nick Brandt and Del LaGrace Volcano. In 2006, it featured a portrait, by Alec Soth, of a bride called Melissa. Although portraiture was an aspect of photography I rarely focused on at the time, this photograph’s technical precision was something to behold. The soft colour palette, the precise composition and focus, and lovely depth of field brought the elements together beautifully. More importantly, I found it gentle and generous, but curious. Where was her husband? Why was she photographed, on her wedding day, outside a rather plain looking hotel? In an article for Magnum, Colin Pantall describes the photograph perfectly,

“Melissa poses outside the Flamingo Inn. She is a big bride in a big dress and looks lovely – but the taffeta white of her wedding gown against the barren walls of her motel talks of how her dreams will fade into a reality beyond her control.” (1)

Whilst I soon moved on from the article, the picture stayed with me, lingering in the back of my mind. This memory proved extremely useful some thirteen years later when I began a master’s degree in photography. The primary focus of the degree’s major project was to produce a work of narrative photography. I had hoped to produce a book that drew inspiration from Robert Frank’s legendary work The Americans. Yet, there was a problem. Scarborough, the district of Toronto that I was calling home felt somewhat devoid of street life.

A new approach was needed, and insight was found in an academic tome that described Soth as one of Frank’s successors in American documentary photography. This led me to recall the fact that Melissa was part of Soth’s book Niagara. A swift visit to the bookshop naturally followed.

Niagara is a book rich with pathos and the humane. It is also, as I noted in a previous column on photobooks, filled with plenty of male appendages! However, what is most notable for me is the fact that, along with its narratives, the book finds exceptional beauty in the banal.

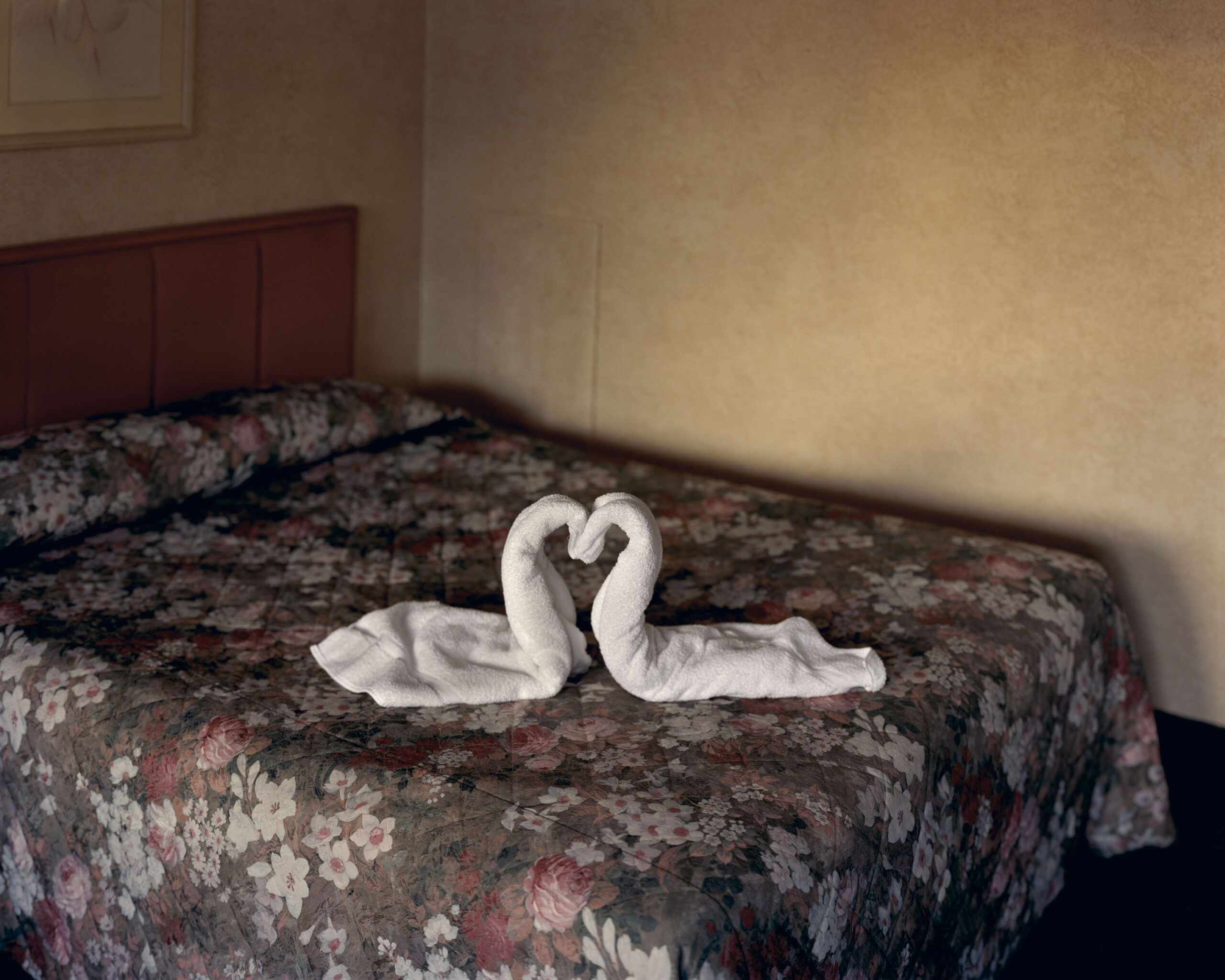

No image illustrates this better than Two Towels. If you explained the photograph to someone without them seeing it: two folded towels on an awful bedspread in a rather seedy-looking motel room, they almost certainly would not believe that the picture was one filled with the beauty of love. These towels, seemingly folded with a genuine romantic spirit, bring to my mind characters from a fairy tale. Before you think me mad, look again and swear that the towel on the left is not a princess plucked from a fairy tale like Cinderella or Beauty and the Beast. Love exists and it can be found here.

Inevitably, Niagara led me to Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi, and no book has had a greater impact on my own creative practice and how I think about narrative photography: not The Americans, not William Eggleston’s Guide, not Paul Graham’s A Shimmer of Possibilities. It is my desert island photobook, and every time I open its pages, I seem to discover something new. Celebrated photography curator Anne Wilkes Tucker wrote in the book’s afterword that “Soth alludes to illness, procreation, race, crime, learning, art, music, death, religion, redemption, politics, and cheap sex”. Yet, whenever I open the work, I find myself disagreeing with her. This is not because I think her wrong, but because I think there is even more to discover in the work. I wholeheartedly recommend that you go and find out for yourself.

One of the most prominent photographs from Sleeping by the Mississippi, our banner image, Peter’s Houseboat, never fails to engage me. Like Two Towels, if you explained its scene to someone and told them that it was compelling without showing them the photograph, you likely would get a rather confused response. Yet again, it is an image that makes something rather prosaic – a houseboat and a washing line – into the beautiful product of an artist’s imagination.

The narratives found in NIAGARA and Sleeping by the Mississippi establish Soth as a successor to Frank, but there is much more to his oeuvre. Although Soth has also produced an exceptional body of monochrome work, best illustrated by 2015’s Songbook, in my eyes it is the colour images that stand tallest. This makes him a natural inheritor of William Eggleston’s world. However, only noting Soth as standing on the shoulders of these giants would be an injustice. He is an artist whose distinctive style automatically marks his most singular images as his and his alone.

It would be amiss to end this discussion of Soth having examined only two of his earliest and arguably most well-known projects. His most recent monographs, I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating and the just published A Pound of Pictures, show a mature artist producing some of his strongest work.

With its title taken from a line in a poem, I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating was made after Soth took an introspective sabbatical year where he produced very little work, an experience that he found tremendously liberating. What followed the pause was a work of lyrical beauty. In fact, it may be the single most beautiful photobook that I have in my collection.

Upon publication, photography critic Sean O’Hagan, writing in The Guardian, noted that Soth’s work is imbued with a “sense of romantic melancholy”, and that the new work was “more intimate and more elusive” (2) than his previous output. O’Hagan, as usual, was precise in his observation. What he did not mention, as perhaps it is not necessary, is that its beauty is, at times, almost overwhelming.

Cammy’s View illustrates this perfectly. It is an image that contains genuine whimsey: an uncaged budgerigar sitting by a window. This alone is cute and funny. Is it pondering freedom from this human enclosure or is it wondering where its bowl of bird seed is? What takes it beyond this is its generous and gentle colour palette. This palette, only broken by four dark-covered books – a pair of Bibles and two copies of the Book of Mormon, fills the image with a sense of tranquillity. As someone who finds it incredibly difficult to find peace within myself, this is the kind of photograph that takes me away from the world.

Soth’s latest book project A Pound of Pictures recalls Sleeping by the Mississippi in that it is based on a series of journeys. Soth had originally intended to follow the route of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train, but the plan soon became a jumble of road trips. It even included a return to his old photographic haunt of Niagara Falls. The complete work, more substantial in length than the other books discussed here, strikes me as a meditation on photography itself and Soth’s own creative practice.

The photograph of the butterfly on the orange slice, taken in Philadelphia, is perhaps my favourite from the book. The splash of orange and the eye on the butterfly’s wing at first draw my gaze, but as I study the picture, I find much more of interest than can be found in the first superficial glance. The textures and markings on the wooden board draw me in and have a visual value all their own. I must stress the perhaps in my choice of favourites. The book has only recently come into my possession. I was happy to purchase a signed copy at The Photographers’ Gallery, that wonderful art space in London, on a recent visit to the country of my birth. It would not surprise me if my opinions on the book evolved as I spend more time with it.

I want physical photography books to hold and spend time with. Looking at pictures online is great, but the book allows you to explore the depths of the work and find its nuances. I think this is one of the critical reasons why I enjoy Soth’s work so much. His emphasis on books reinforces what I believe to be the most critical and truest part of our philosophy here at FRAMES – Good photography belongs on paper. Of course, it is not only Soth’s commitment to the book that makes these objects so wonderful. It is also the superb printing and presentation of the work by Mack books.

A recent photographer featured in this column said that what I had written about their work made them blush and that I had perhaps been a little too kind in my words. I freely admit that most articles that I write for the Look Closer column are overwhelmingly positive and full of praise for the artists I write about. That is the exact reason why I began the column. I want to write about photography that excites and compels me. This is unquestionably the case here. The work of Alec Soth has had a profound effect on how I approach and create my own photography. Long may that continue.

His new book A Pound of Pictures can be bought from Mack Books.

Another new publication, Gathered Leaves – an annotated exploration of five of Soth’s most well-known books can also be found at Mack.

(1) Interview with Alec Soth, The Guardian

(2) Revisiting Alec Soth’s Niagara, Magnum Photos

ALEC SOTH