When you hear the term “Defender of the Faith” you may at first think of one of the formal titles given to Queen Elizabeth II, but as FRAMES is a photography magazine and website, this is not our subject for today. The “faith” that I want to talk about here is the one that drives photographers to make images using technology long past what many would consider its use-by date because of an unshakeable belief that this technology makes images of quite extraordinary power and presence. I am talking here about large format photography and the glorious images produced by these cameras.

So many of us have switched entirely to digital that it is well worth remembering that some of the very finest and most beautifully detailed photographs ever taken were made by these great beasts of cameras, and this includes modern work. Every single one of us with more than a passing interest will be aware of the historic work of the likes of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. It was large format cameras that enabled them to produce their greatest works (1, see below). Our banner image today features one of these magnificent historic works. This one, Canyon de Chelly by Edward Curtis, was one of the artists favourite photographs. For me, it exemplifies the grand scale embodied by large format photography. Most large format images are made on a 4’x5’ or 8’x10’ negative. Curtis, however, used an enormous 14’x17’ view camera. The result draws you into the vast, ancient landscape like no other photographic medium.

Despite the age of the technology, it is one that many lauded modern photographers work with. For example, Alec Soth’s brilliant books Sleeping by the Mississippi, NIAGARA, and I know how furiously your heart is beating were all made with large format equipment as was Robert Polidori’s discomforting but superb Zones of Exclusion: Pripyat and Chernobyl. I could go on, but the point here is that whilst large format photograph is old-fashioned, it is most certainly not a dead or obsolete process.

Beyond the cameras and the film, there is another commonality between these wonderful works – time. These are images that must be made slowly. There can be no rushing around, clicking the shutter at anything and everything you see. The image must be composed and focused, and the single sheet of film loaded into the camera before the shutter can be clicked. The photographer must be patient, deliberate, and precise. For me, the consequence of this is that the large format images of the finest photographers always seem so deeply considered; they invite the viewer’s contemplation. When I look at the pictures, they make me want to understand the subject intimately and comprehend what is being signified by their rich detail. The inspiring results make me yearn to buy a 4’x5’ or 8’x10’ camera and learn the process.

In the FRAMES Facebook group, a member asked a thoughtful question about whether we laud images that use alternative or historic processes just because they use such processes. This question is worth a great deal more debate that can be conducted here. However, our three new images for this article would be wonderful regardless of the method of production used. Although from three different genres, they are all stirring and show true mastery of this traditional photographic craft.

Our first image is taken by a photographer who takes the recreation of historic film processes to a quite extraordinary level. Shane Balkowitsch is a self-taught photographer who creates his images using the historic Ambrotype process which was an evolution of the wet collodion plate method (2, see below). It was created in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer and today is used by only around a thousand photographers globally. The original process was extremely dangerous and used hazardous chemicals including potassium cyanide in its production. Fortunately, safer chemical alternatives have been found. However, this makes Balkowitsch’s work no less remarkable.

Images such as Kaylee Ruth LaCompte, “Little Shining Star”, Hunkpapha Lakhota / Sichangu Lakhotaconjure up a lost nineteenth century past. Taken as part of a twenty-year project entitled Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective that documents the native people of North Dakota and its neighbouring states, this beautifully crafted photograph, with its lovely use of light and shadow, highlights the beauty of a striking young woman. She might be modern, but her traditions are evident and are accentuated by the historic styling of the picture. The image naturally reminds the viewer of the great works of Edward Curtis. Critical arguments have been made with regards to Curtis’s working methods and how he represented his subjects, but these most certainly do not apply to Balkowitsch’s work. He works entirely in conjunction with the indigenous people and was given the highly appropriate name of “Shadow Catcher” by the Hidatsa Nation in 2018.

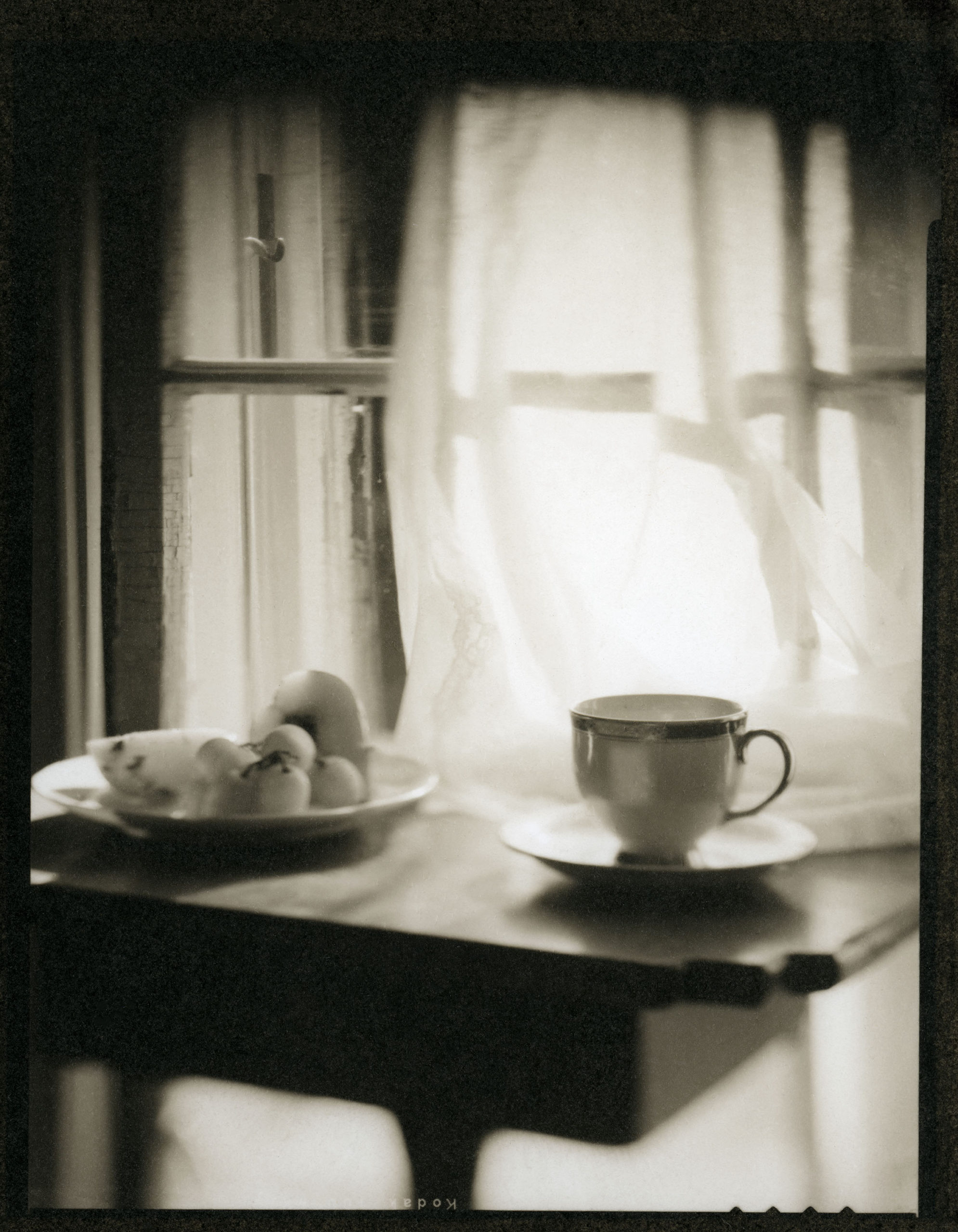

Our second image, Trapped no. 1 by Caroline Waterman, seems to hark back to another age with its gorgeous platinum tones creating an otherworldly atmosphere. At first, it seems almost casual: a perhaps discarded cup of tea left next to a plate of fruit and an open window. Yet, the composition is immaculate, and all the elements come together perfectly. However, what really makes this image for me is the curtain. It is brighter than both the cup and the plate of fruit, but rather than distract it adds another layer of atmosphere to the picture, and the fact that it appears to be moving adds yet more depth. It asks us to consider what is going on behind it. This is a world of the photographer’s imagination wrapped up in a 4×5 frame, and it is lovely.

Irish born, but calling the USA home, Waterman has spent many years with photography. However, it was not until she completed a BFA in photography in 2016 that she switched her concentrated and attention to large format photography. Her work focuses on her Irish heritage and those closest to her, and also explores themes of loss and a dread of loneliness and separation. These approaches, both creative and technical, have clearly paid dividends. Her superb work has been displayed in multiple exhibitions in recent years.

Our third image comes from landscape photographer Lynn Radeka, who has had a long and illustrious photographic career. His work emphasises the best of landscape photography’s traditional values and is included in multiple books including the 2005 publication The World’s Top Photographers: Landscape where his work was featured alongside such luminaries as Yann Arthus-Bertrand and Art Wolfe. In addition, he was asked to make a series of prints from the Library of Congress’s collection of Ansel Adams’s negatives. These honours illustrate Radeka’s dedication to both the aesthetic and technical side of his craft.

The image itself, Moon Over Zabriskie Point, could have been plucked straight from the golden age of American landscape photography. This picture, certainly sublime rather than picturesque, captures the spirit of Death Valley’s forbidding yet wonderous landscape. Its tonal range, running from the brightness of the moon to deep blacks in the mid and foreground, is exceptional. If you claimed that either Weston or Adams had taken this image, nobody would doubt you such is its impact. I believe that this photograph embodies what Robert Adams was thinking when he wrote the essay Truth and Landscape. Like our other images, it is a delight to behold and would grace any wall.

This article has been a joy to write. It has stirred my sense of nostalgia for all things film. It has encouraged me to purchase a large format camera of my own although I hold no pretensions about producing such luminous work. However, most of all it has been a pleasure spending time with such inspiring work. I very much hope that you feel the same.

(1) For an explanation of how large format photography works follow this link.

(2) Details of the Collodion process can be found here.

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Shane Balkowitsch

WEBSITE

DOCUMENTARY “BALKOWITSCH” ON AMAZON PRIME / ON VIMEO

Caroline Waterman

WEBSITE

Lynn Radeka

WEBSITE

Shane Balkowitsch

January 11, 2021 at 16:54

It is an honor to be featured, thank you so much Rob Wilson and Frames Magazine.

Robert Wilson

January 11, 2021 at 17:34

My pleasure!

Caroline

January 11, 2021 at 18:55

Thank you , this is a wonderful article and it is an honor to be featured .

Robert Wilson

January 11, 2021 at 21:12

My pleasure!

Lynn Radeka

January 12, 2021 at 04:44

Fantastic article Rob! I am honored that you included me!

Robert Wilson

January 12, 2021 at 14:05

The honour is all mine!

Talal Hrout

January 18, 2021 at 19:47

Totally agree that it is the time taken and the process to produce these images is what worth thinking of and appreciating !!!

Well thought article !

Robert Wilson

January 18, 2021 at 19:51

Thank you!