There is a photograph that I took some years ago that troubles me. I am not sure if it is because I feel like I should not have taken it or because what it shows outrages me like no other picture I have ever taken. It raises questions in me about my approach to photography and what images I should and should not share.

The picture, taken on the streets of India’s capital Delhi, shows a homeless man sitting curled up with his head on his knees facing away from the camera below a large poster advertising sporting goods. It shows Lionel Messi’s portrait and has the words “Never Follow” emblazoned below him. I took the picture because the scene before me made me angry. I found the disparity between the poor soul on the ground and the implied affluence of the poster disgusting. The idea that millions can be spent on advertising a pair of football boots whilst others have nothing is morally reprehensible. Perhaps I am being naïve or overly idealistic here, but it is the way I feel.

I do not consider the picture good enough to include here, but I have shown the image publicly once. This was at a talk I gave some years ago to a group of students at the university where I was then working. The purpose of the talk was to encourage them to think about the possibilities of photography beyond snapshots, selfies, and Instagram lifestyle pictures. The students were overwhelmingly from extraordinarily affluent backgrounds. One colleagues at the university used to joke that he had never seen so many young people driving such expensive cars and that the average student car was far more valuable than all the ones owned by the faculty. I am uncertain whether photography had any impact on them, but I believe it was an appropriate forum to share the image.

I still ask myself whether I was ethical in making that image. I consider myself a documentary photographer, but I am not a photojournalist nor was I making the image as part of a commission or project. At the time, I just saw the scene and made the picture for no purpose beyond the fact that I thought I should. I do not have an answer for my own question but constantly challenging and reviewing my own behaviour as a photographer is always a useful exercise.

I was brought to the topic of ethics for this article not by my story above, but by a recent series of incidents that occurred in the parklands of the Guild Park and Gardens, a place of historic interest and natural beauty located along the Scarborough Bluffs in eastern Toronto, Ontario. The eighty-eight-acre area provides a habitat for many rare flora and fauna. Recently, a rare Eastern Screech Owl took up winter residence in one of the trees in the park. This arrival prompted an influx of what volunteer group Friends of Guild Park described on its Facebook page as “bird paparazzi” who proceed to harass the owl and break park rules. According to the group, these individuals,

• Crowded through off-trail areas into wooded areas – habitats for native plants, many of them so rare that they are protected by legislation.

• Surrounded the owl roost for hours, upsetting the bird’s normal routine of rest and feeding

• Began shouting at the owl, even shaking trees and branches to make the owl more visible as they tried to get a “trophy” photo of the bird in action.

Vickie Bowie’s image above illustrates this absurd behaviour perfectly. As the statement from the Friends of Guild Park says, these people are disturbing protected habitats. Frankly, this idiotic behaviour makes me embarrassed to own a camera. This is photography as nothing more than trophy hunting. This unethical behaviour has led to ‘corrective’ action. Guild Park has not banned bird photographers entirely, but it has installed protective barriers. Thankfully, Bowie and most of her fellow bird photographers who enjoy Guild Park’s opportunities are conscientious and committed to conserving the species that live there.

Obviously photographing bird life and people enduring homelessness could not be more different in terms of application and technique. However, they are closely related in terms of how we behave as photographers. There is a difficult question here though. What exactly is ethical behaviour in photography? What makes something unethical and unacceptable?

Our ethical codes are our own. Our parents, education, politics, beliefs – religious or otherwise, and a whole laundry list of elements that I cannot even begin to list enable us to arrive at our own code. Clearly, it is not for me to tell you what to do. For myself, I tend to take a “I know it when I see it” approach. Obviously, I do not approve of the behaviour of these idiots misbehaving at the Guild Park, but that is a clear-cut situation. Others require more nuance. For example, while I have no issues about documenting poverty and homelessness as they are a very real part of life, I do not consider creating stylised photographs of those in straightened circumstances which beautify their condition and make them look somehow angelic as ethical. This is not to say that photographs of those homeless cannot be beautiful. Don McCullin made some images of London’s homeless that are beguiling. The question for me is intention. Why are you making the image? What is its purpose? If the answer is “art”, I suggest you think again.

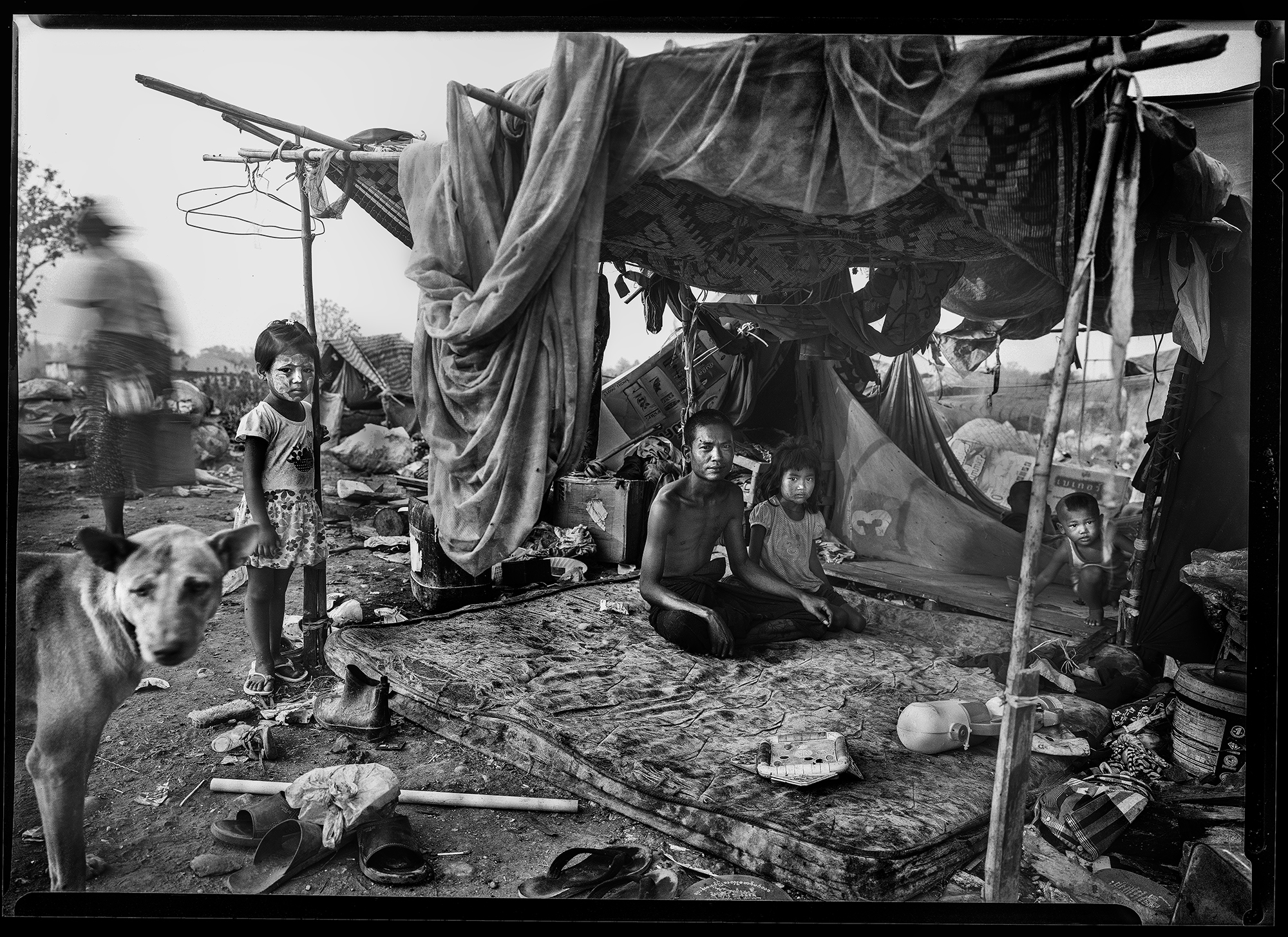

For the second part of this article, I would like to focus on a body of work that gives an excellent illustration of how to be ethical and humane when dealing with an emotive subject. The photographer is Gerry Yaum and the project is called The Families of the Dump. Whilst the images are finely crafted, I must admit that when I first saw the project, I was sceptical about the content and intent. I always am with work that covers this kind of subject matter. However, after reading Yaum’s account of the project, spending more time with the images, and conversing with Yaum himself, I am sold on the value of this outstanding work. Like much of the work of Sabastiao Salgado, the dignity of the subjects is preserved throughout.

I am not going to review the images as such here as that is not really the focus of this article. However, I will say that they are very fine indeed and fully deserve their publication on photographic merit alone. In fact, the work, along with his other project The People under the Freeway, is scheduled to be exhibited at the University of New Brunswick Arts Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada from October 28th, 2022, to December 15th.

Yaum has spent many years working as a night-time security guard and chose the Thai word for security guard – yaum – as his artist’s pseudonym. He is conversant in Thai and spent four months creating the project. His own words describe his experiences perfectly.

The garbage trucks would arrive at around 8pm and 11 pm in complete darkness. The family groups of over 50 people would wait in the dark for the trucks then work the new garbage after it arrived. Often young children would accompany their parents as they worked, waiting near-by, they would play in the garbage or sleep, sometimes work.

My process was to arrive via motorbike at around 7pm or a bit later and stay until around 1230 or 1 am photographing that night’s events. I did that probably 5 out of every 7 days for the 4 months, it was exhausting and filthy. The strength of the families is amazing. At the beginning of the night on first arriving I would hand out headlamps, boots, medicines, foods etc along with mama noodles and lollipops for the children. The lollipops would be handed out throughout the night, usually 30 plus per evening. When I ran out of goods, I would take orders for the next day. I got good at saying things like, HEADLAMP, BOOTS and TOMORROW in Burmese. The goods were bought with donations made after people saw the photographs, or from exhibition artist fees and talk fees I received. When I did not have enough money, I used my security guard money to buy things (YAUM means “Security Guard” in Thai).

Yaum’s commitment to the story and the people he photographed over an extended period along with the sensitive and thoughtful images that he has produced provides an excellent example of how to be ethical and humane when dealing with a challenging and difficult subject. The project is infinitely stronger because of this approach. He could have made images which descend into ‘poverty porn’, but it is to his immense credit that he has not. They tell an important and unflinching story.

Documentary and wildlife photography are very different parts of our wonderful craft. Yet, ethics connects them. This article has looked at when photographers have failed to be ethical in their approach but has also focused on what can be achieved when you approach a project with decency and sensitivity. I genuinely believe that most of the readers of this column already consider the ethics of photography when they work, but if not, I hope that what you have read here encourages you to make it a critical part of your practice. Ethical behaviour was very much at the centre of Gerry Yaum’s excellent project and for me, this serves as a far better exemplar of how to behave with your camera than a bunch of fools who thought it acceptable to disturb an owl.

I would like to extend additional thanks to Ann Brokelman and John Mason at Friends of Guild Park for their kind assistance in the completion of this article.

GERRY YAUM

WEBSITE

Slate’s coverage of one of Yaum’s earlier projects

VICKIE BOWIE

Frank Styburski

January 26, 2022 at 20:35

Thanks for the article, Rob.

This is a subject that I think about a lot. I see so many images published today whose intent is to gain notice simply because of their provocative nature, without respect for the subject’s humanity.

You might make a case for the propriety of such images when they are made of celebrities or politicians, in unflattering situations. They are public figures, after all. You might even argue that compromised pictures bring the subjects more attention, and work to their advantage. But this raises the question of whether, even the most public of figures, deserves a moment of invisibility.

The paparazzi will decline to self-regulate claiming duty to their jobs, & citing a demand in the market for them. And deference to simple human decency is an irrelevance in the context of competition and free commerce. Occasionally, the consequence is tragic, as in the case of Princess Diana.

More difficult to judge is the work of respected art photographers like Diane Arbus. A case could be made that her images are exploitative. Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl” image has also gotten some criticism, recently. So has the iconic 9/11 image that Time Magazine used of a man in free fall after jumping from the World Trade Center. An argument could be made that they reveal some profound truth about our nature that we might not understand without them. And an equally valid argument could be made that what these pictures contribute could be achieved with more sensitivity, in other ways.

As a photographer, I had an epiphany like yours. It was over an image that I made that was visually exciting, but unflattering to the subject. It was taken on a public beach where there was no expectation of privacy. The woman’s back was turned, so I could have shown it without revealing her identity. Yet I didn’t feel like that understanding extended to publication or a gallery wall.

I felt that it would have been a violation of her humanity to exploit the encounter. My decision might have been different if my purpose was to achieve attention, or if I had a commercial purpose. I think that our identity as photographers are a small part of who we are. Ultimately it seems to be a balancing act between our personal needs as image makers and our moral values that define the rest of who we are.