As someone who works in a camera shop, I often get to meet a range of interesting people. This is particularly true now that I live in Canada’s capital, Ottawa. I have met at least one ambassador, two MPs, and several of the most highly respected photographers in the city. A reasonably well-known Hollywood celebrity even comes into the shop occasionally. Recently, a gentleman came into the shop for a passport photo. I asked him what sort of passport it was for. He told me that it was for a diplomatic passport as he was being sent overseas for an assignment. This piqued my curiosity (or is it my general nosiness?), and I asked if he was going anywhere exciting. He shook his head, told me that he was being sent to South Sudan, and admitted he was not looking forward to it.

A whole range of travel advisories from multiple different governments illustrate why the diplomat was so apprehensive. The US Embassy in the country offers a “level 4” travel warning and tells people not to travel. The UK Foreign Office advises against all travel to the country. The Canadian Government website simply states, “Avoid all travel” in a big red banner. Similar messages come from Australia and elsewhere. The message is unequivocal. I thought little more about it beyond removing it from any list of potential future travel destinations.

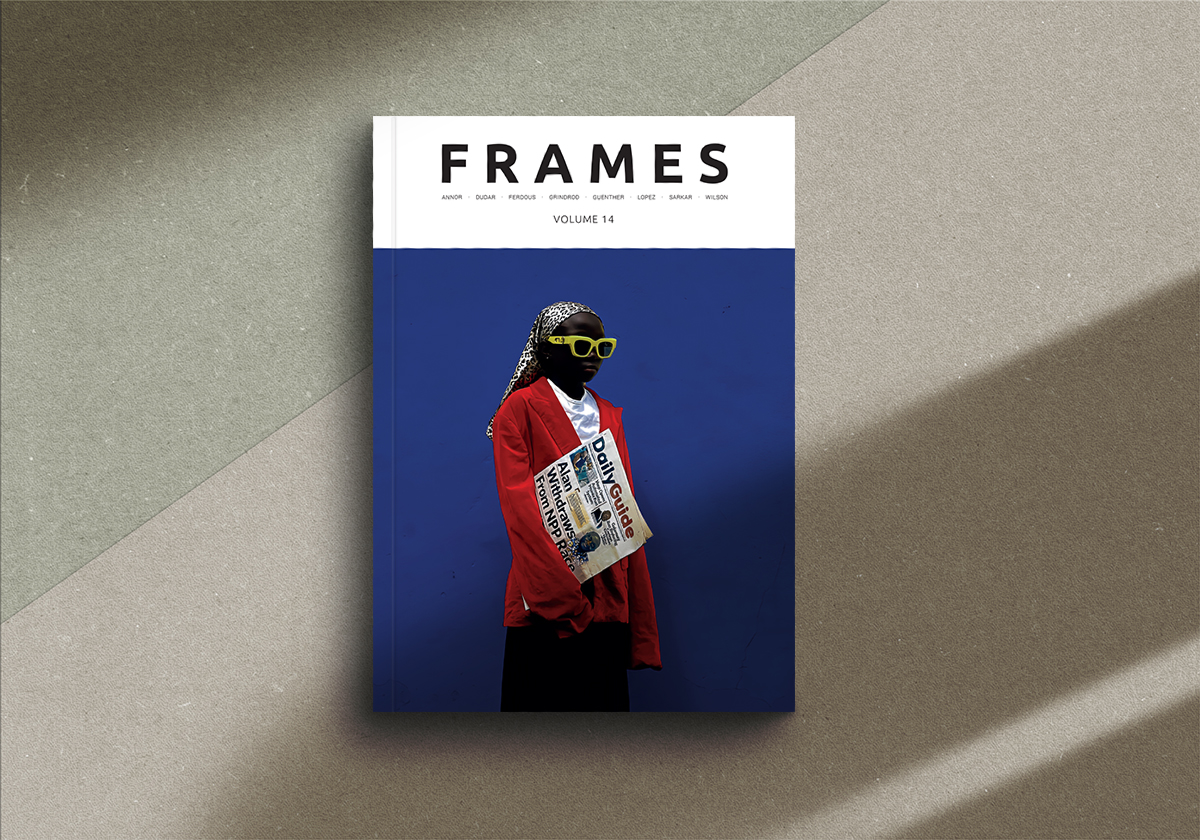

© Peter Caton

However, I was intrigued when a friend from my days teaching English in Oman posted on Facebook that he had attended a talk by a photographer who he had known since their schooldays together. The talk was about a three-year project in South Sudan that documents the catastrophic floods that now plague the country. The work is a story of the devastating impact of climate change and its direct effects on people who are among the least responsible for its occurrence. The photographer responsible for this quite remarkable work is Peter Caton.

© Peter Caton

Caton has so far had a substantial and successful photographic career which focuses on humanitarian issues. An early life in Scarborough, England, where his parents ran a children’s home, followed by a degree in photography made a career in socially conscious photojournalism a natural fit. After travelling around Asia in the mid-2000s, Caton decided to pack his suitcase permanently and live life on the road as a full-time freelance documentary photographer. Since then, he has worked and travelled continuously for seventeen years, but returns to the UK once or twice a year. He has worked globally and has completed major projects in many countries including Bangladesh, Brazil, Chad, India, Namibia, Somalia, and Uganda. These projects have covered a diverse range of subjects including climate change, drought, famine, leprosy, eyesight, gender and sexuality, and mother and child mortality. Every single one of these projects shows an impressive dedication to humanity and our planet. Many of the projects make uncomfortable but vital viewing. They have been featured in a diverse range of publications that include the Guardian, the BBC, the Washington Post, Marie Claire, and the Sunday Times Magazine. In addition, his portraits of the victims of leprosy were exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Whilst they are all outstanding projects, for me, it is his work in South Sudan, which I am honoured to feature in this article, that is the pinnacle of his output so far.

© Peter Caton

Caton found his motivation for the South Sudan project in his faith. Whilst in church three years ago, he prayed for guidance on where he should go next. “The next moment I opened my hymn book to sing a hymn and there was a tiny flag of South Sudan. I knew then that I needed to work there,” he tells me in an email. Whether the source of Caton’s motivations resonates with you or not, you cannot but help be impressed by the immense dedication and commitment to this remarkable project his faith has brought him.

In our email exchange, I ask how he feels about South Sudan. He feels that the country is young and in critical need of attention from the international community. The region is particularly susceptible to the horrors of the climate catastrophe but receives little attention and funding. The money that it so desperately needs is being spent elsewhere. This makes projects like Caton’s not just necessary but vital.

© Peter Caton

Looking through the project’s images, I find a sense of collaboration between the photographer and the subjects. These are not people who are unwilling to be subjects. Caton tells me that the people were keen to be photographed and he never once had any problems making images. People wanted their story to be told and appreciated the efforts being made. His photographs, along with accompanying stories and reports by journalist Susan Martinez, who also spent the last three years visiting the country, has done much to raise awareness of the issues at hand as well as generating financial aid for the region. Tragically the floods are not going away. Caton tells me that the region is expecting them to be even worse this year and that “these vulnerable communities are bracing themselves”.

© Peter Caton

As I look through the collection of images that Caton shared with me, I am struck by a feeling of permanence to the flooding. The water is not going away. The impact of our self-made climate disaster is visceral and painful to see. It has put these people in an utterly desperate situation, short of both food and shelter. They are forced to adapt to and deal with a tragedy for which they are entirely blameless and cannot prevent. Yet, the photographs are not entirely without hope, and that comes from the people featured in the images. These people, despite their dire predicament, project resilience and an extraordinary strength. They are not going to give up.

© Peter Caton

I think the resilience and permanence come through in the images that I have chosen to feature in the article. These exceptional photographs need little commentary. The photographs are made using a Hasselblad H5D 50c, a superb piece of equipment which ensures the highest image fidelity. Caton’s own personal ‘signature’ is his use of a mobile lighting setup that generates a studio-like quality in many of the images. Perhaps my favourite is our banner image which shows a group of women standing above what appears to be a rice paddy. There is a range of emotions on the faces of the women, but what seems to come through most of all is the humour in being photographed and the joy in each other’s company. There is some optimism here, and it comes from the strength in these women.

© Peter Caton

I am often given to photographic existentialism and ask myself questions like “What is photography?” or “What is the point of photography?”. Work such as what Caton has produced gives an easy answer to both of those questions. Detailed text descriptions of each photograph as well as the individual stories of the subjects can be found accompanying many of Caton’s images where they have been published elsewhere. However, I have presented the images with only the overall background for context precisely because they answer these two questions, and, for me, no further text is necessary. You do not need a single word to see the stories in the images. The viewer can draw their own accurate inferences and come to conclusions about what is going on. This is photography at the core of the medium: pictures which tell you a story. In this case, a very real one. If, after viewing some oversaturated hyper-processed monstrosity masquerading as reality, I ask myself the second question, I only need view work like this to understand that there is very much a point to photography.

© Peter Caton

PETER CATON

You can find more information on the situation in South Sudan as well as make a donation to an appeal at Action Against Hunger.

Sabur

October 3, 2022 at 20:10

I think it has covered an answer to Tomasz ‘s question of the last week’ Is this a photograph ?’ Great human document!

Rob Wilson

October 26, 2022 at 18:33

Glad you liked it!