Rob Wilson examines the work and legacy of Julia Margaret Cameron.

If you close your eyes and try to imagine what Henry the VIII looked like, I suspect what comes to mind will not be an actual human being, but a painting. I am reasonably confident that you are now picturing a version of Hans Holbein’s lost but much copied painting: a corpulent but confident Henry, dressed in his regal finery, standing with legs apart and hands on hips. If you are not imagining this, perhaps it is the actor Jonathan Rhys Meyers who played Henry in The Tudors that you see in your mind’s eye. How about William Shakespeare? What do you see when you call him to mind? I daresay it is either a painting again, one of a number that may show the Bard, or Martin Droeshout’s rather poor-quality engraving. Otherwise, it is conceivably the actor Joseph Fiennes from Shakespeare in Love. Let us try for a third. What about Charles Darwin?

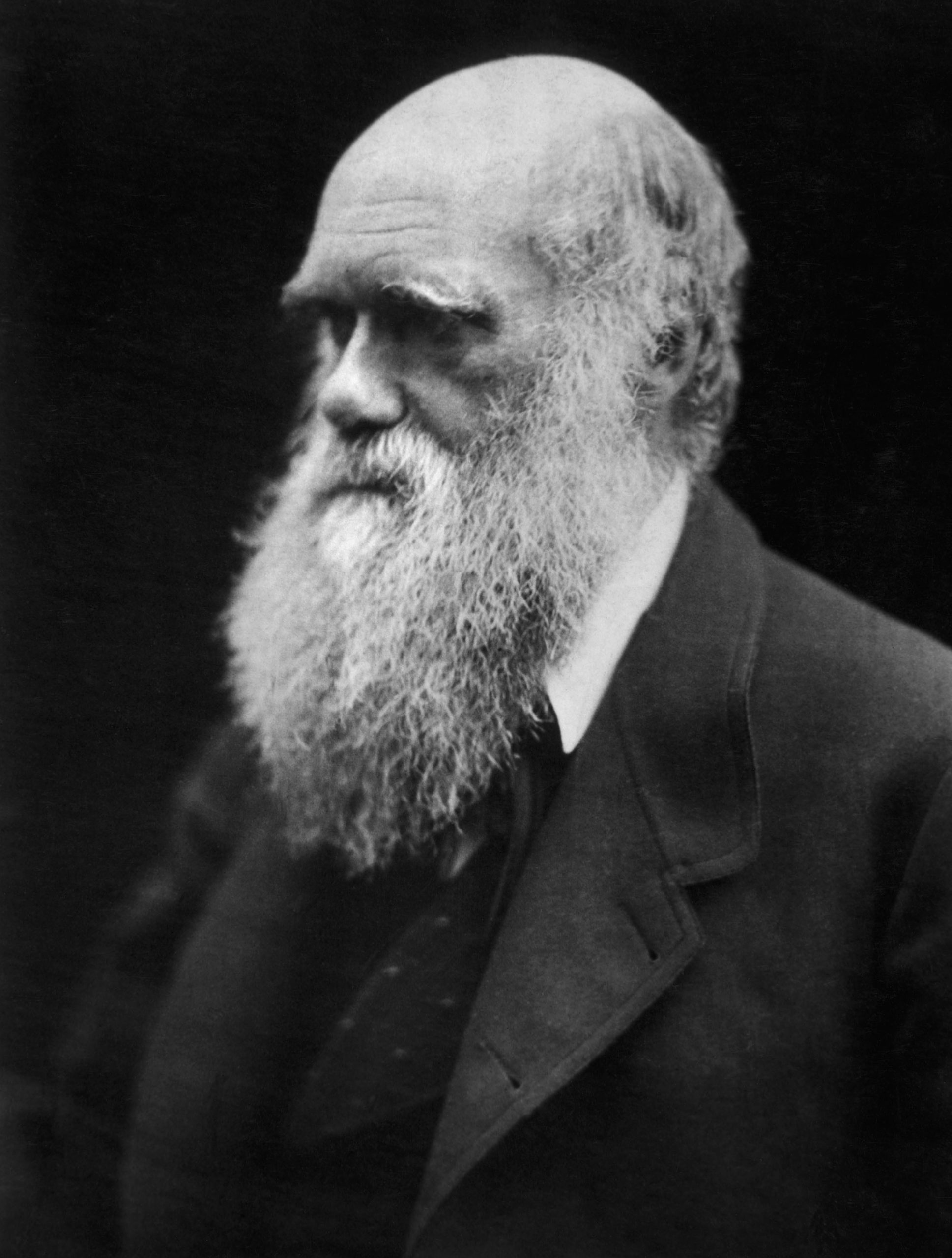

When I think of Darwin, I imagine an old man with a bushy white beard and bald pate. He looks a little sad and reflective yet grand and dignified. I am guessing that this is the Darwin you imagine as well. There is no need to recall a painting or an actor’s portrayal because this is the Darwin of Julia Margaret Cameron, who photographed him on at least three occasions (a fourth similar portrait is attributed to her but may have been taken by Darwin’s son Leonard). Cameron’s portraits capture the essence of the popular vision of the man. In fact, she iconises him. The man in her photographs is the one who theorised evolution, who explained life, who changed the way we look at the world, and who still upsets many a creationist today.

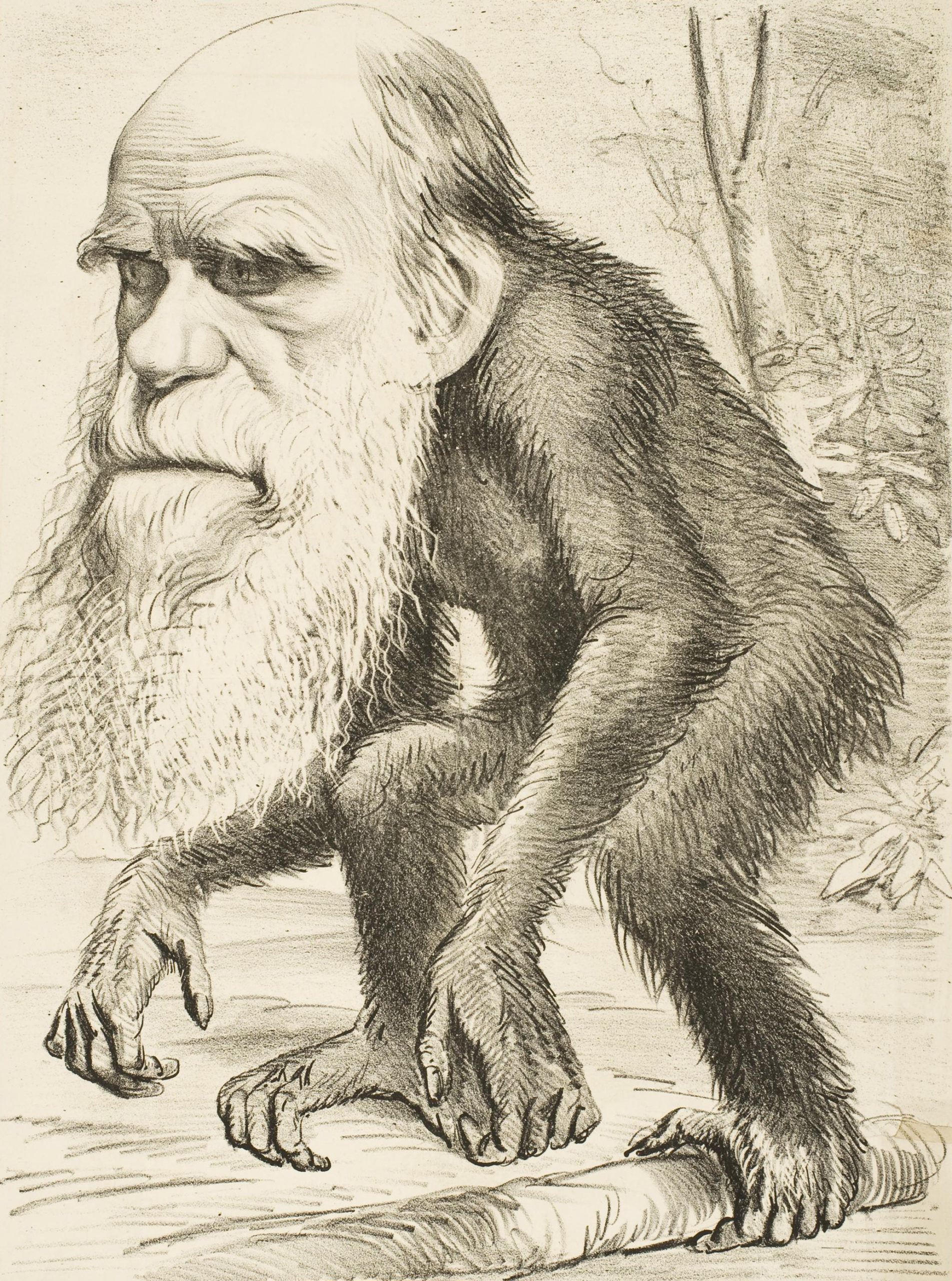

Caricatures of Cameron’s portraits followed soon after their creation. In a well-known example, a cartoon from the The Hornet magazine placed Darwin’s head on the body of an orangutan. This image has also endured. An internet search for ‘Charles Darwin as a monkey’ will reveal multiple similarly styled cartoons, all with one thing in common: every single one uses Cameron’s Darwin as its basis. Not all representations are so unflattering as evidenced by the cover of the first issue of the 2019 volume of Skeptic magazine, which featured a modern painting of him on its front cover. It was again based on Cameron’s Darwin.

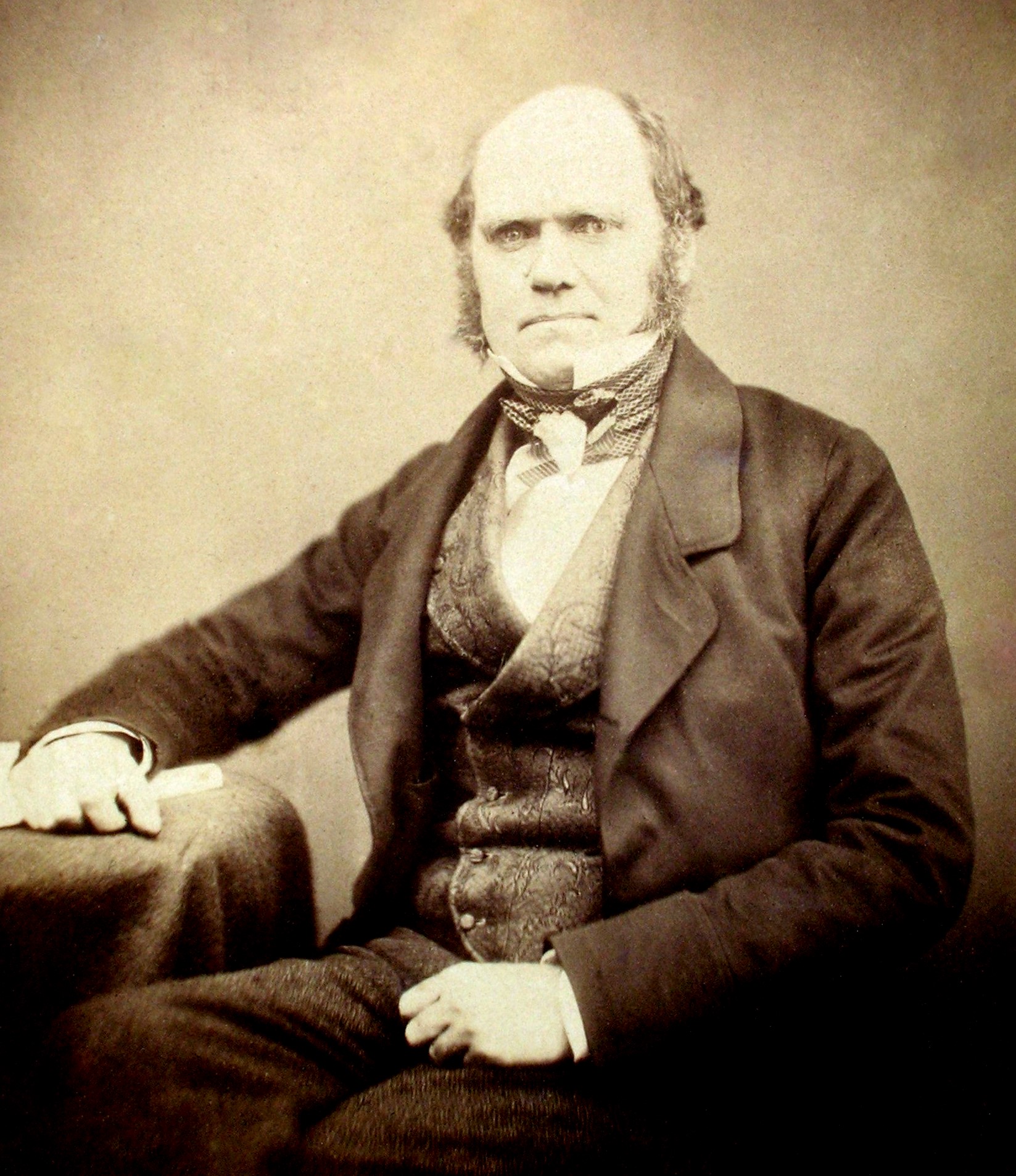

Cameron was neither the first nor last to photograph Darwin, yet it is not difficult to see why it was her image that has endured. In Maull and Polyblank’s 1855 portrait, he cuts a faintly curious figure: uncomfortable, stiff, and wide-eyed. Upon seeing the portrait, Darwin wrote, “if I really have as bad an expression, as my photograph gives me, how I can have one single friend is surprising” (1). He was photographed numerous times by others after Cameron (despite looking elderly in her famous portraits, he was not yet sixty!). However, the pictures that followed seem somehow derivative and just variations on Cameron’s theme. She created an emotional and iconic connection to Darwin that cannot be found in any other image of him with the possible exception of Herbert Rose Barraud’s 1881 portrait, the last known photograph of the great man.

What of the photographer herself? Julia Margaret Cameron was born in India in 1815. Her father was an East India Company official, and her mother a French aristocrat. She was educated in France before becoming a well-known socialite in British-ruled India. In 1845, she and her husband moved to England. Remarkably, it was there, at the age of forty-eight, that she took up photography, her first camera a gift from her son and daughter. Perhaps even more surprising is that she appears to have given up photography entirely upon leaving England and retiring to Sri Lanka. Her career lasted a mere twelve years.

Over the course of those twelve years she only made around 900 images, but what images many of them were! Her connections allowed her remarkable access to some of the most well-known figures of the day. Besides Darwin, she also photographed Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Sir John Hershel, among others.

Cameron was a deeply religious woman who saw her photography as a spiritual endeavour. She wrote, “When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer.” (2) Initially, her work was not universally popular, but her portraits of those considered the great and good of the era, particularly those of men, have stood the test of time. Her other work is perhaps of only moderate interest, though many commentators may disagree with this assessment. That said, the best of her work is more than sufficient to guarantee her legacy among the greats of photography.

For me, it is fair to remember her as Britain’s greatest portrait photographer of the Victorian era. She illustrates one of photography’s greatest gifts: the recording of the past. As history moves forward, the proportion of famous and historical figures whose faces are unseeable will continue to decrease. That we, and future generations, can look upon photographs of Darwin, Lincoln, Churchill, and other important historical figures is a testament to one of the medium’s remarkable qualities.

(1) https://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/…

(2) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/…

Nigel Walker

July 10, 2020 at 21:12

Great article. Her work was not popular largely becasue she took less time over the post production than many of those around her. Yet the blurs and scratches actually seem to add to the photographs for me and she is one of my top thirty photographers in my world (although my favourite picture of hers is Sir John Herschel).

Rob Wilson

July 11, 2020 at 14:01

Thanks Nigel!

Glad you enjoyed the article. The Herschel picture is wonderful.

Dick Winters

July 11, 2020 at 19:47

Thank You. Once I started I loved learning and having your perspective.

Rob Wilson

July 11, 2020 at 20:50

My pleasure!

John griffiths

November 21, 2020 at 08:49

Looking at older classic style alternative format portrait photography fills with awe and inspiration as modern imagery can be disappointing in its clinical perfection. Á proficient portrait on film complete with colour cast, dust and scratches seems to indicate to me the possible imperfection of both the system and the sitter. It is peculiar how the imperfections seem to ad to the composition instead of the opposite placing it in the the perspective ziet geist, one cannot imagine a digital snap achieving that in the future. Julia Margaret’s work also shows us the art of filling a frame without crowding it and suffocating the borders. A great exponent of fine portraiture, a shame she chose her career with a camera to be so short. A great article, thank you.

Robert Wilson

December 28, 2020 at 00:12

Thank you John. I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Luiz Henrique Xavier

December 31, 2020 at 15:07

Great article !

Robert Wilson

December 31, 2020 at 21:52

Thank you!