November includes what I regard as one of the most important days of the year. It is Remembrance Day, also known as Armistice Day, Poppy Day, and Veterans Day. As I am sure you know, it recalls the moment in 1918 that the fighting and killing formally ended, and the guns went silent. It did not signal the official end to the First World War. That moment came at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, but it is the day that many countries have chosen as the appropriate moment to commemorate and remember those who have died in conflict.

It is personal for me as I remember a great-grandfather who never got to see his children grow up or meet his grand and great-grandchildren. I remember a great uncle who was little more than a youth when the Second World War took him from his family. And I remember a teammate from my rugby playing days who never made it home from the Balkans. I am quite sure that each of you has a similar family story.

This year, my wife and I attended the commemorations here in Ottawa. I am happy to say that the Royal Canadian Legion organises a beautiful, meaningful, and moving event in the city that I now call home. All who attend are made to feel part of the event. It was a privilege to see a flypast by a Spitfire and a Hurricane. Additionally, it was sobering a hear to a field gun fired twenty-one times. Every time the gun was fired, I felt the soundwaves vibrate through my body. This was only a small cannon. Much larger artillery was used in both World Wars. The noise then must have been terrifying.

Of course, we were unable to resist taking our cameras to the event. This accounts for the candid portrait that my wife made with her beautiful vintage Rolleiflex TLR that forms the banner image for this article. I hope you can forgive my nepotism in leading with her photograph, but I make no apologies for including the image. I think it is a lovely photograph that captures the emotion of the day perfectly.

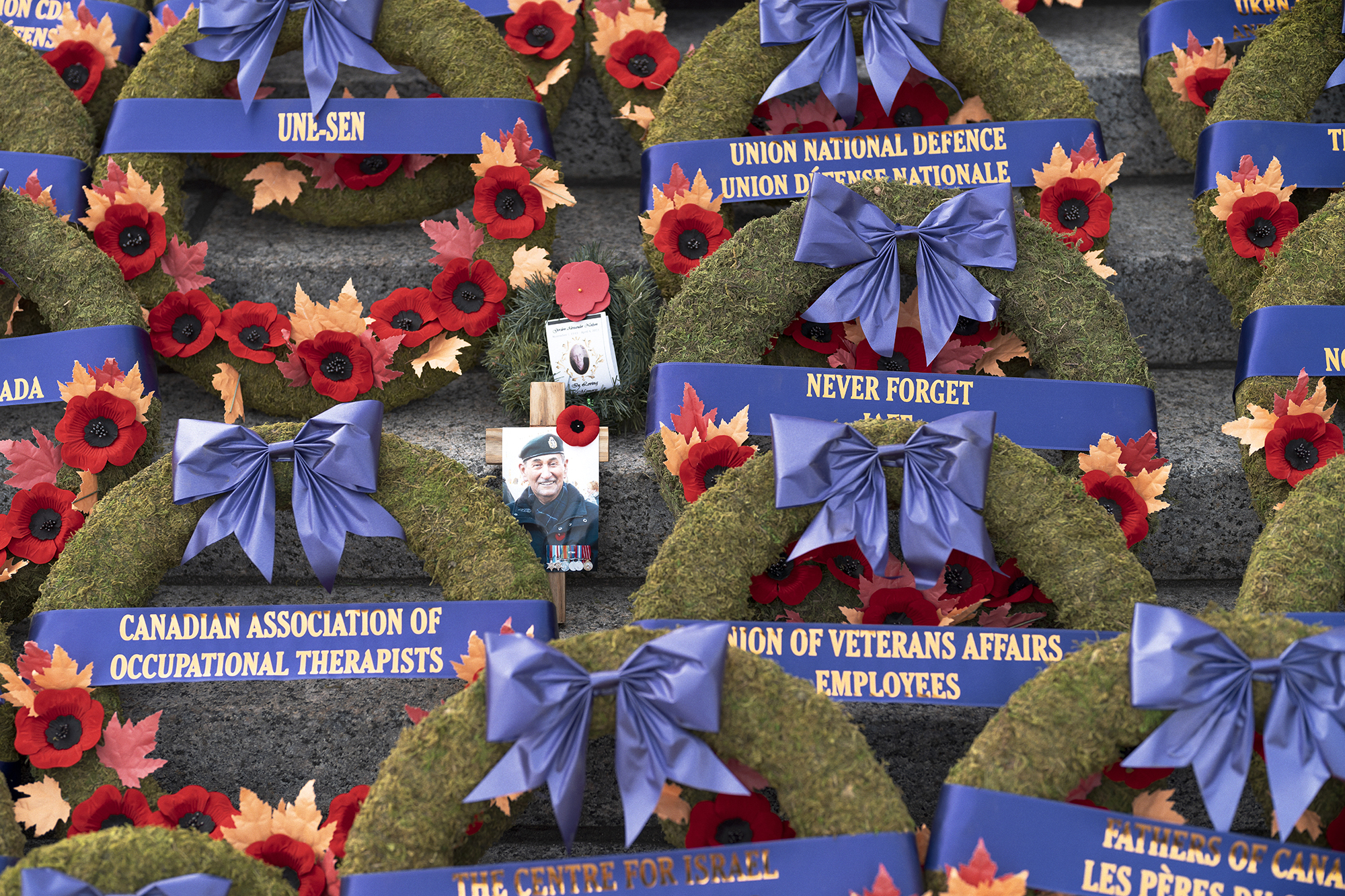

At the conclusion of the formalities, the public are allowed and encouraged to approach the cenotaph and to place their poppy on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. After making our own visit to the tomb, we spent some time walking around the wreaths that various officials, embassies, and organisations had placed on the cenotaph. Here, I came across two photos that had been left with the wreaths. The more prominent of the two was a picture of an old soldier, his chest adorned with medals. Seeing these pictures in conjunction with the events of the day got me thinking about how photography connects to our memories and perceptions of war and conflict. I believe that photography and its connection to conflict is critical in the formation of our collective memories. This connection, even without consideration of everything else that photography has brought to the world, makes the creation and evolution of the medium one of humanity’s most important endeavours. Photography is not the only thing that keeps events in our consciousness, but it is one of the things that makes our view of the past so much more vivid, visceral, and tangible.

First, let us consider the An Lushan Rebellion. I would be willing to bet that for most people their reaction to this would be “The what rebellion? Never heard of it.” This would not be a surprise. It is a war near lost in the mists of history. Yet, the conflict, which took place in China between 755CE and 763CE, may have been one of the bloodiest horrors that humanity has ever inflicted on itself. The census of 755CE registered the population of China at nearly fifty-three million people. The first census after its conclusion gave a population of under seventeen million. What? A death toll of thirty-six million people? Scholars dispute the actual figure with thirteen million seemingly a more likely butcher’s bill. However, considering the global population at the time, this is still a monstrous proportion of the world’s inhabitants.

Now arguing that these appalling events are mostly forgotten only because there are no photographs would be tenuous in the extreme. In fact, trying to claim that any war remains in our consciousness only because of photographs would be foolish. However, I am confident that if we move a millennium forward in time when the First and Second World Wars are as distant a memory to humanity as conflicts such as the An Lushan Rebellion, the Avar Wars, and the Goryeo-Khitan War are to us, the wars of the twentieth century will be far more easily recalled and imagined because of the photographs.

When I first began formulating this article in my mind, one photograph that I thought would illustrate my argument effectively was Roger Fenton’s great image Valley of the Shadow of Death. The picture, described as “the first iconic photograph of war” by filmmaker Errol Morris, purports to show the valley where the suicidal cavalry charge of Tennyson’s great poem The Charge of the Light Brigade took place – “Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do and die. Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred.” The picture brings an extra dimension to Tennyson’s chilling words. The cannonballs scattered across the valley fill the viewer with horror. How terrifying it must have been to face the guns!

Yet, there is far more to this picture than what meets the eye. There is another version of this image that has no cannonballs on the road. Fenton may well have moved them into the road to create a more dramatic scene. In this pre-photojournalism era, this would not have created any issues for the photographer, but today it would have probably cost him his job and reputation as the unfortunate Narciso Contreras found out when he was sacked by the Associated Press in 2014 for cloning a video camera out of an image of a fighter in Syria. (Contreras took full responsibility and apologised for his actions. Thankfully, the talented documentarian has repaired his reputation with his subsequent work.) I have mentioned Fenton possibly moving the cannonballs in an earlier article, but what I did not know and find more shocking is the fact that the image was not taken where the Charge of the Light Brigade took place. The actual battle took place several miles away. The photograph might well create a vivid image of a distant war long out of living memory, but it is most certainly not modern photojournalism.

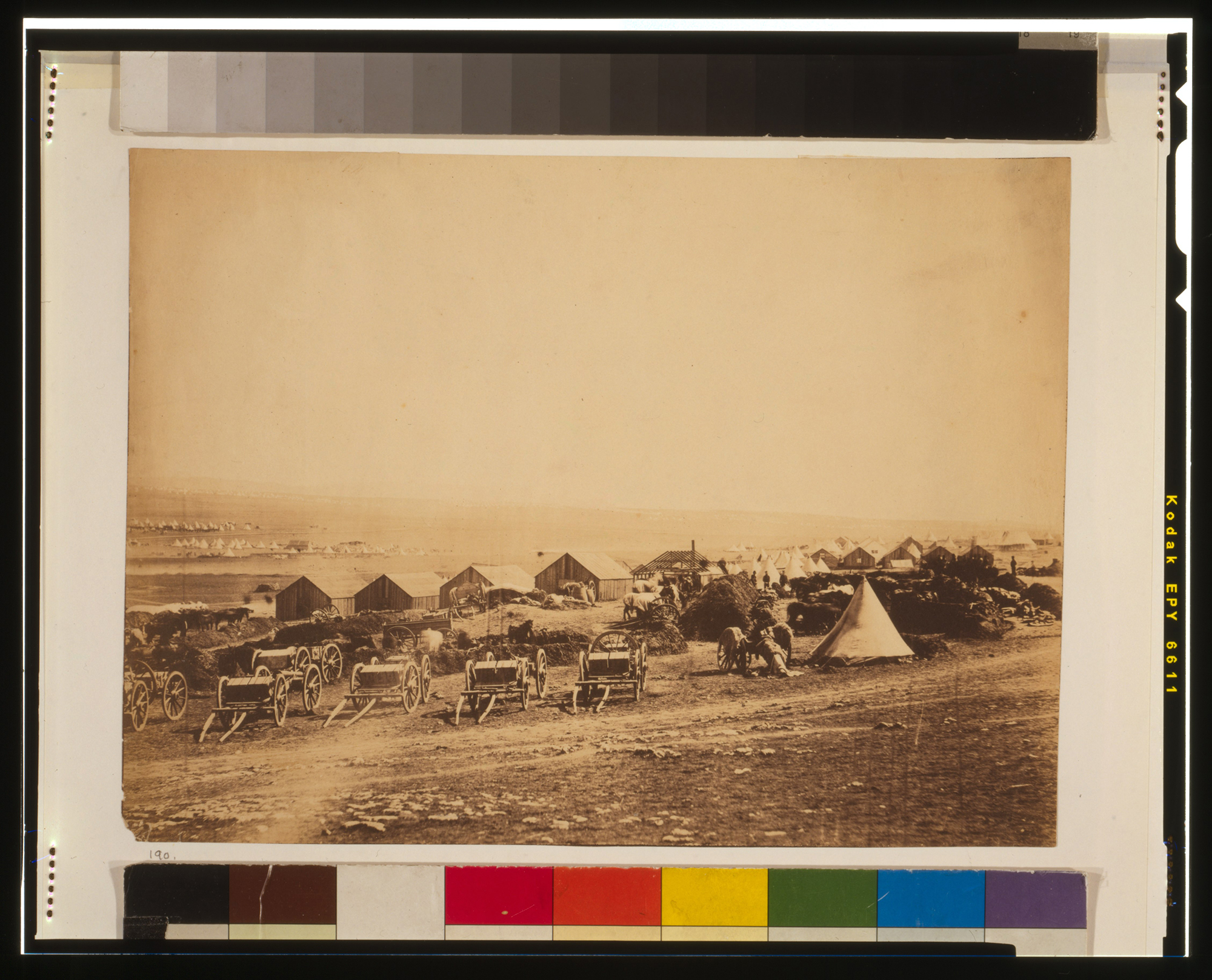

Fenton’s other images are wonderful and really bring the era alive, but they have that static quality typical of work from the 1850s – the portraits are obviously staged and in other scenes everything is fixed to a point. This is not a criticism, but simply a reality of the long exposure times required by the technology of the time. However, except for the clever understatement of the setup Valley of the Shadow of the Death, they do not capture the horrific reality of war. For that, we need to move forward to the 1860s.

The American Civil War was the first time that photography really demonstrated the visceral and grim nature of conflict. Many photographs featured mangled corpses rather than posed officers, horses, and camps. The photographer from this war that I find most interesting is Alexander Gardner. Gardner was a Scotsman who immigrated to America in 1856. He worked with Matthew Brady, perhaps the most celebrated photographer and photography business owner of the era. However, in my personal opinion, Gardner made the more interesting images.

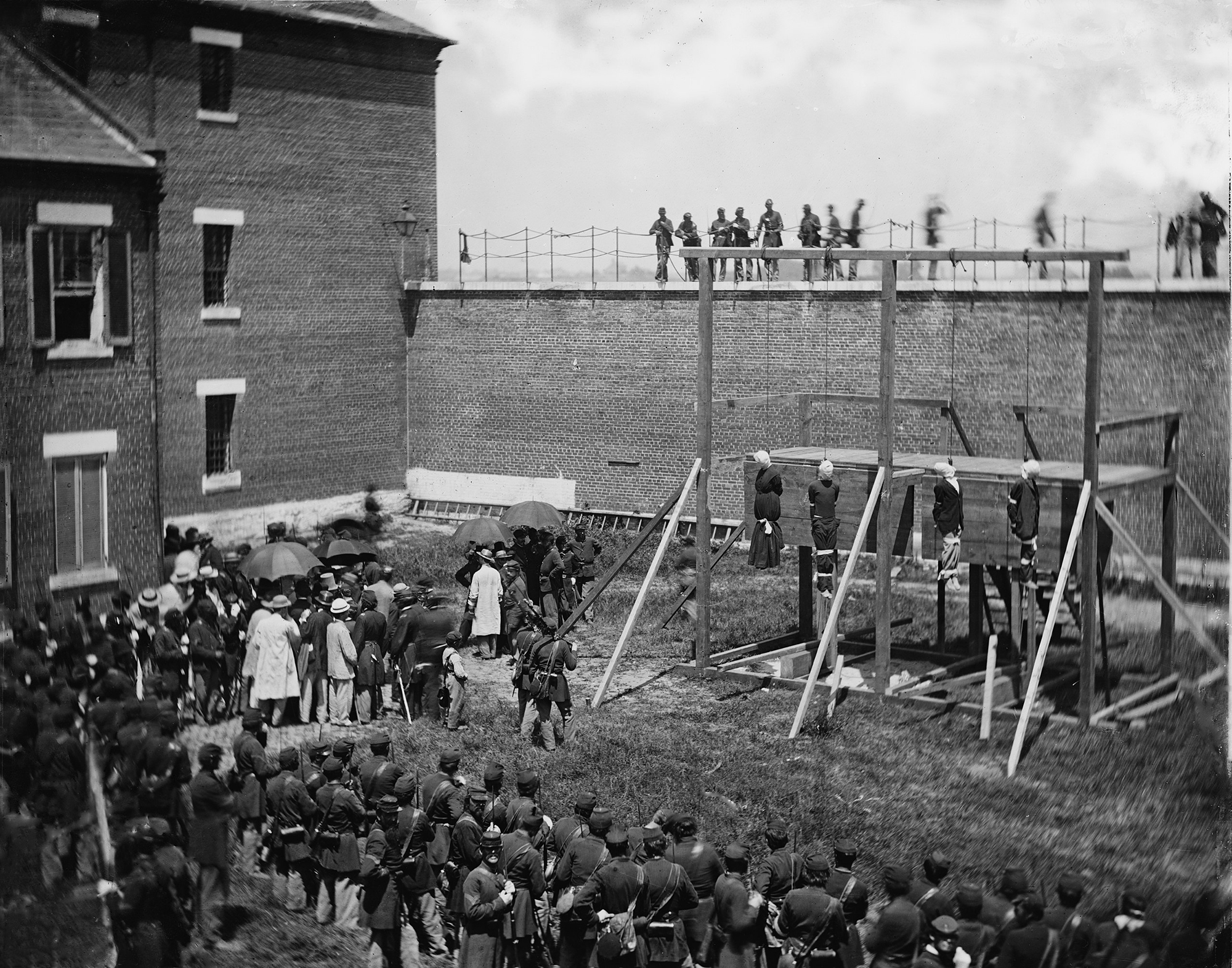

There is an immediacy and dynamism in Gardner’s Civil War images that cannot be found in Fenton’s Crimean work. His photographs of the war and its consequences are unflinching. The two photographs we feature here, one showing Confederate dead and the other the execution of the conspirators in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, are still brutal and gruesome for viewers today. They are meant to shock and do so effectively. I find the execution scene particularly extraordinary. Events of a century and a half in the past are brought into sharp focus. It recalls Lynsey Addario’s devastating photograph of a Ukrainian family struck by Russian mortars[1]. Addario’s photograph was made because it documented a war crime. Her works shows that war has consequences. Gardner, so many years earlier, did the same.

Yet again though, things are not always as they seem. Modern research suggests that Gardner and his team of assistants, which included another early great of photography in Timothy O’Sullivan, moved corpses around and staged some of the images[2]. This revelation left me wondering if I still felt the same about his photographs, so I paused the writing of this article for a few days and reflected on things. Perhaps, this is not a good idea as the first thing my imagination conjured up was the conversations that must have taken place during the creation of the images – “Timothy, can you bring that body over here? Yes, the one with the arm missing. And don’t forget his head!”

Eventually, I came to a more serious conclusion. It does not change how I feel about the photographs. Gardner was following the practices of the time. There was no such thing as photojournalism in the 1860s and I suspect that nobody had even begun to consider anything like a code of ethics when it came to the photographic documentation of war. The modern viewer should understand what took place when the images were created, but they still provide an invaluable and extraordinary record of the shocking reality of what happened when a nation went to war with itself. There are far more reasons why the American Civil War is, and must continue to be remembered, than I, as a non-historian, feel able to discuss in an article such as this one. However, I believe that the extraordinary images that Gardner and other photographers of the time created make it even more visually tangible than would otherwise be.

This becomes increasingly true as we move into the twentieth century. Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier or Loyalist Militia Man at the Moment of Death are the defining images of the Spanish Civil War. His photographs of the D-Day landings do the same for that extraordinary event. There are few conflict images as rousing as Joe Rosenthal’s remarkable capture of the flag being raised on Iwo Jima, a photo so extraordinary in its power that it was used as the model for the US Marine Corps War Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Conversely, there are few as devastating in their indictment of war as Don McCullin’s photograph of a starving albino child during the Biafran War or his picture of a shell-shocked marine after the Battle of Huế. We can no longer separate war from its photographs. They are now a constant and critical part of its landscape. I have an impossible hope that I can hop forward in time a thousand years to check whether I am correct in my belief that the biggest conflicts of the 20th century will still have an immediacy to them because of the vast treasure trove of photographs. This is mere speculation of course, but I hope that this article has shown that there may be some merit to it. Lawrence Binyan’s heartbreakingly beautiful poem, For the Fallen, now known to most as The Ode to Remembrance, tells us that

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn;

At the going down of the sun, and in the morning,

We will remember them.

He was right, of course, we do remember them, and very often that memory is through photographs.

[1] https://www.boston.com/news/world-news/2022/03/08/lynsey-addario-photo-mother-two-children-killed-ukraine/

[2] Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg | The Art Institute of Chicago (artic.edu)

Cary Wasserman

November 28, 2022 at 00:00

No photograph better epitomizes war itself, nor specifically the American Civil War, than the Timothy O’Sullivan “Harvest of Death.” And as a cautionary tale, so that we may be alert to preventing rather than limited to documentation, Hiroshima and Nagasaki images of incinerated citizens including those that are nothing more than shadows on the city walls. (Without overlooking the two iconic Vietnam images of Kent State and the fleeing napalmed victim of the chemical industry’s contribution to war technology, or the Middle Eastern long-distance war strikes).