Rob Wilson examines the work of Ragnar Axelsson, the Icelandic photographer who documents the Arctic’s threatened cultures.

I still remember the first time I saw Robert Doisneau’s Kiss by the Hotel de Ville. I was a teenager and the moment I saw that image, I wanted to be a photographer: a dream I would not fulfil until many years later. My wife often jokes that I am the least romantic man in the world. Yet to this day, the picture still makes my apparently hardened heart soar. Another image which had a similarly immediate impact on me was Eugene Smith’s Three Spanish Soldiers: a picture of such powerfully sinister intent that I have to force myself to look away from the dark gazes of the fascist regime’s civil guardsmen. This kind of effect is rare. The work of most photographers normally comes to my attention over time. Yet, there is one photographer, previously unknown to me, whose work struck me with more immediate drama than I experienced before or since. The pictures were a beautiful punch in the face: a joyful left hook to the senses. These pictures still mesmerise me to this day, and their creator is Icelandic photographer Ragnar Axelsson.

In the winter of 2012, I was flying home to the UK from my then home in Seoul, South Korea. The airline was a solid, dependable carrier with fine service, but, if I am honest, it had terrible inflight entertainment. I had used them previously and spent 12 hours reading rather than endure a miserable selection of films. However, on this occasion when looking through their guide, I happened upon a documentary called Last Days of the Arctic, which was about Axelsson photographing life in the Arctic regions of Europe. Of course, I was and still am a sucker for anything related to photography, so I watched it. In fact, I watched it twice: once on the way to the UK and then again going back to South Korea. The documentary was an excellent piece of filmmaking, but the pictures it featured enthralled me even more. They brought a very human face to the impact of climate change and mourned the destruction of traditional ways of life.

Axelsson’s best work is a lament for what will be lost to climate change. This creates poignant undertones in so many of his images. The communities and cultures shown in his pictures are on the edge of extinction and will be gone without immediate action. The environments he shows, which genuinely contain Robert Adams’s “three verities”, are spellbinding, but they also emphasize what is at stake if we do nothing. It is the inclusion of these subtexts that makes these already wonderfully compelling images unforgettable.

Our first image is one which stood out dramatically in Last Days of the Arctic. In 1995, an avalanche struck the village of Flateyri in Iceland’s north west. Homes were lost. People were buried, and twenty lost their lives. After the tragedy, Axelsson in his role as photographer for the newspaper Morgunblaðið arrived to document the story and its aftermath. At a church service which followed a rescue operation, Axelsson took this image. It is one of quite remarkable power and pathos: a baby gazes upon the photographer. Opposite is an adult, perhaps a rescue worker, with head in hand. It is an image that captures the numbing horror of the disaster but juxtaposes it next to the wide-eyed innocence of the baby. It tells us life will continue no matter what. What is to come will not be stopped by the past, and the child embodies this. There is hope for the future and it is in the face of the child.

Our second image and article banner– Old man on the black beach – is, I believe, the photographer’s signature shot. In Last Days of the Arctic, Axelsson himself mentioned how he saw the entire history of the Icelandic nation on the man’s face. He is correct, but I would go further still; it feels as though Iceland’s geography is also contained in this one photograph. Interestingly, the image draws comparisons with photographs from Robert Frank’s The Americans. On the surface, it has some of the same elements of almost haphazard composition, but there is nothing so random here at all. The placement of the man emphasises his position as part of the environment and as a man of his landscape. It makes a fine lead image for this article.

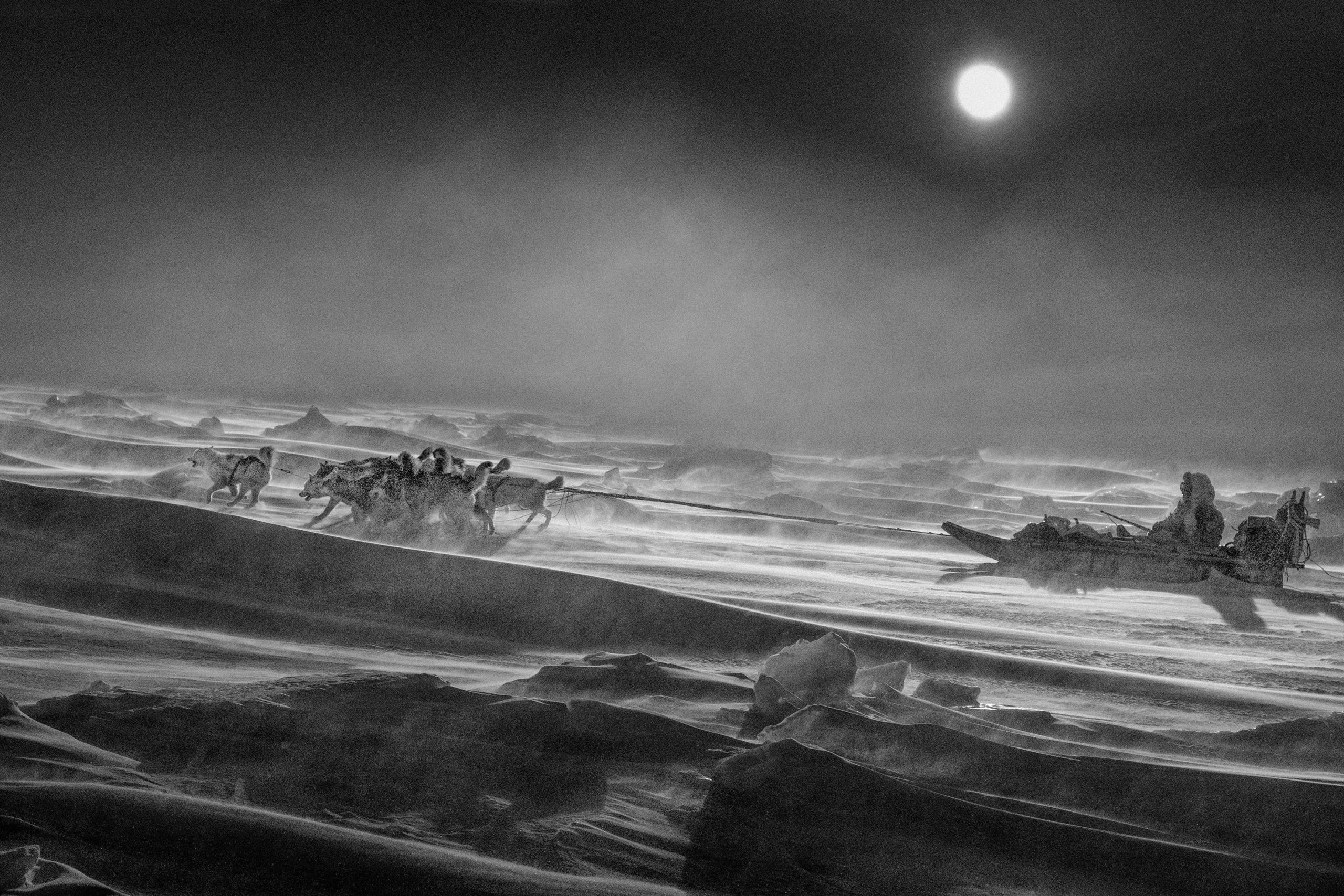

For the final three images, I am delighted to present pictures from Axelsson’s new book: Arctic Heroes, which will be published in Europe in December and North America in February 2021. The label “heroes” is well chosen. You can feel the strength of both humans and dogs in these images. The inhospitable climate is tangible in all three photographs, but is felt most particularly in Thule, Greenland. The ice and snow cut through the image. This is not a place for the weak hearted. In the second photograph, Mats Ole cuts an extraordinary figure wrapped in his furs. This is a hostile place, but Ole is the man to survive here. Finally, the dog brings us an ambiguity. Is it angry, barking, and hostile? Is it curious and friendly? The picture does not answer this question but leaves us to make our own judgement. Like the others in this new work, it is an exceptional image.

So often, photography about communities and traditional ways of life is done by outsiders, but Axelsson documents his own culture as well as others with which he is intimately connected. His images bring us their stories. Every time I study his images, I leave desperately wishing that these are not the last days of the Arctic. I hope you do, too.

P K

November 11, 2020 at 03:41

‘Old man on the black beach’ is such an iconic photograph and one that I only knew from the cover of Sólstafir’s 2014 cover of their album Ótta. I always wondered about that photo and oddly enough was discussing this with a friend the other day.

Robert Wilson

November 11, 2020 at 14:12

Great! It certainly is iconic.

Nigel Walker

November 11, 2020 at 12:17

Great article. I photographed in the interior of Iceland last year and it is an amazing country with an indelible landscape. The elements are raw and more changeable than a pair of socks. Great article. I have not knowingly seen his work before so thanks for drawing it to my attention. Off to see if I can discover the documentary now …

Robert Wilson

November 11, 2020 at 14:12

Thank you Nigel!

Good luck with your search for the doc.

Gregory George

December 14, 2021 at 19:41

One of my very favourite photographers. Wonderful piece, Rob. As I mentioned to Tomasz in the Facebook Group, it would be wonderful to see a full Ragnar feature in the magazine. Here’s hoping!

Robert+Wilson

December 15, 2021 at 14:06

Thank you Gregory!