When I first immigrated to Canada in early 2019, I decided to halt my career in education and, with the kind support of my wife, become a student again at almost fifty years old and pursue a master’s degree in photography. We realised that I needed to be somewhat financially useful, so it was agreed that I would get a part-time job. I also knew that whilst I had a decent understanding of the history and culture of photography, I had minimal knowledge of camera technology. This was a situation that needed rectifying.

Fortunately, I was able to find part-time employment at a camera shop here in Toronto’s fascinating and unfairly maligned district of Scarborough. My time at the shop has been a genuine pleasure. The store’s management team are good hearted and fair, and my diverse group of colleagues are fine company. I am happy to count them all as my friends.

In addition, the shop has brought me into contact with a remarkable range of people. These have included a pop star who produced a song that went gold and a YouTuber with a quarter of a million subscribers. I have met hundreds if not thousands of others. From the talented young wedding photographer frustrated that she could not afford the equipment to support her manifest ability to the couple who wanted their wedding from the 1940s(!) digitised, I have enjoyed meeting them all. However, there is one meeting that I suspect will stay in my memory longest of all, and it was one that led to this article.

People often come to the store to make while-you-wait digital prints of photographs. Recently, an older lady asked me to scan and print two photographs that she passed over the counter. It was immediately obvious that these were not ordinary snaps. Yet, they seemed to be printed on card rather than photographic paper. This made me curious. I first wondered whether they had been cut out of a book. Now as I am a bit nosy, I asked who had taken the photographs. The reply stopped me in my tracks.

“My late husband took them in the 1950s. He received the Order of Canada for his photography.”

This was how I came to meet Margaret and discover the remarkable work of her husband, Richard Harrington. We had a fascinating discussion about her husband and his photography which led to her suggesting that I contact Toronto’s Stephen Bulger Gallery for help in creating this article. The gallery was only too happy to help.

Richard Harrington was born in Germany in 1911, but little is known about his early life. He never publicly revealed his birth name nor any great details about his life before he came to Canada. In a photography career spanning over forty years, he was both widely travelled and published. His extensive travel log lists destinations across Canada and the world. He worked from the Yukon to Canada’s maritime provinces and from Nigeria to Peru. His pictures were published in magazines such as National Geographic and Life. His work continues to be exhibited as part of The Family of Man exhibition that is permanently on display at Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg.

Harrington, by all accounts a humane and decent man, passed away in 2005 at the grand age of ninety-four. As a photographer, he is best remembered for his images of the Padleimiut people. In 1950, Harrington travelled to a remote area west of Hudson Bay and found a community in serious trouble. The Padleimiut relied on the caribou for food and resources, but when migration routes changed, they were left facing starvation. One entry from Harrington’s diary is harrowing:

Came upon the tiniest igloo yet. Outside lay a single, mangy dog, motionless, starving … Inside, a small woman in clumsy clothes, large hood, with baby. She sat in darkness, without heat. She speaks to me. I believe she said they were starving. We left some tea, matches, kerosene, biscuits. And went on.

His obituary in the Toronto Star reported that Harrington, along with making a series of powerful but humane photographs, gave the people what he could and alerted the newspaper about what was happening. The media reported that at least 60 members of the community had died of starvation. Yet, the response from the Canadian Government was slow and the suffering continued. Eventually, the Government relocated around half of the survivors in 1959. This in itself was a controversial act, and there is a belief that these relocations were primarily about securing Canadian claims overs Arctic territory.

My own discovery of the story of Caribou Famine and Harrington’s role in reporting it comes at a time of soul searching and reflection in Canada over the country’s relationship with and treatment of the First Nations people. So far, over 1300 suspected grave sites have been found at many former residential schools where indigenous children were placed during the 20th century. In these schools, the majority run by church authorities, many children were subjected to unimaginably horrific treatment. The death toll remains unclear as only a fraction of the former school sites has been searched for graves.

I do not want to comment at length with regards to the crimes and horrors of the residential school as this is neither the forum for such discussions nor do I feel I have the expertise. In addition, excellent analysis and reporting can be found elsewhere. However, I will state that the story of Caribou Famine adds to a history of seemingly conscious cruelty and deliberate neglect on the part of the country through much of the 20th century. I can only hope that a path to reconciliation can be found.

The quite extraordinary image Padlei, NV that features as our banner is one that confronts and challenges the inaction of the Canadian Government during the famine. When I consider and review images that I find are extremely strong, one of the first things I do is carry out a mental exercise that attempts to juxtapose the photograph alongside other great images that carry similar messages. The immediate reference point for this picture is, of course, Dorothea Lange’s portrait of Florence Owens Thompson widely known as Migrant Mother. Harrington’s photograph has the same universality: a mother’s desire to protect and love her child. The picture is hypnotic and compelling.

During the writing of this article, I feel as if I spent as much time looking at this photograph as putting words on a page. It demands that I look and acknowledge the subjects and their lives. When I turned away from the image, I was left wondering what became of the mother and her son. I felt that the photograph would continue to haunt me as, unlike the relatively well-documented life of Florence Owens Thompson, I could locate no record of what happened to the woman and her son. Thankfully, just before publication Stephen Bulger kindly sent me an old scan of a Toronto Star article from 2005. The low-resolution scan was extremely difficult to read, but it revealed that the mother, a woman named Keenaq and her son, Steven Keepseeyuk, had survived. Keenaq had gone on to have two more daughters. Steven was not only “alive and well” but was living “a rich and happy life”.

Is the image perfect? In our precise modern terms, perhaps not. Picky viewers might note that there is a little too much negative space behind the child, but to see this as significant would be to miss the point of documentary photography. In a previous column, I noted that Lange had missed the appropriate focus point in Migrant Mother, but nobody cares because it is not important. It is the same here. The power of this image is in the expressions of the mother and child and the contact between their faces. Like how Migrant Mother is one of the great American photographs, Padlei, NV is one of the greatest Canadian images.

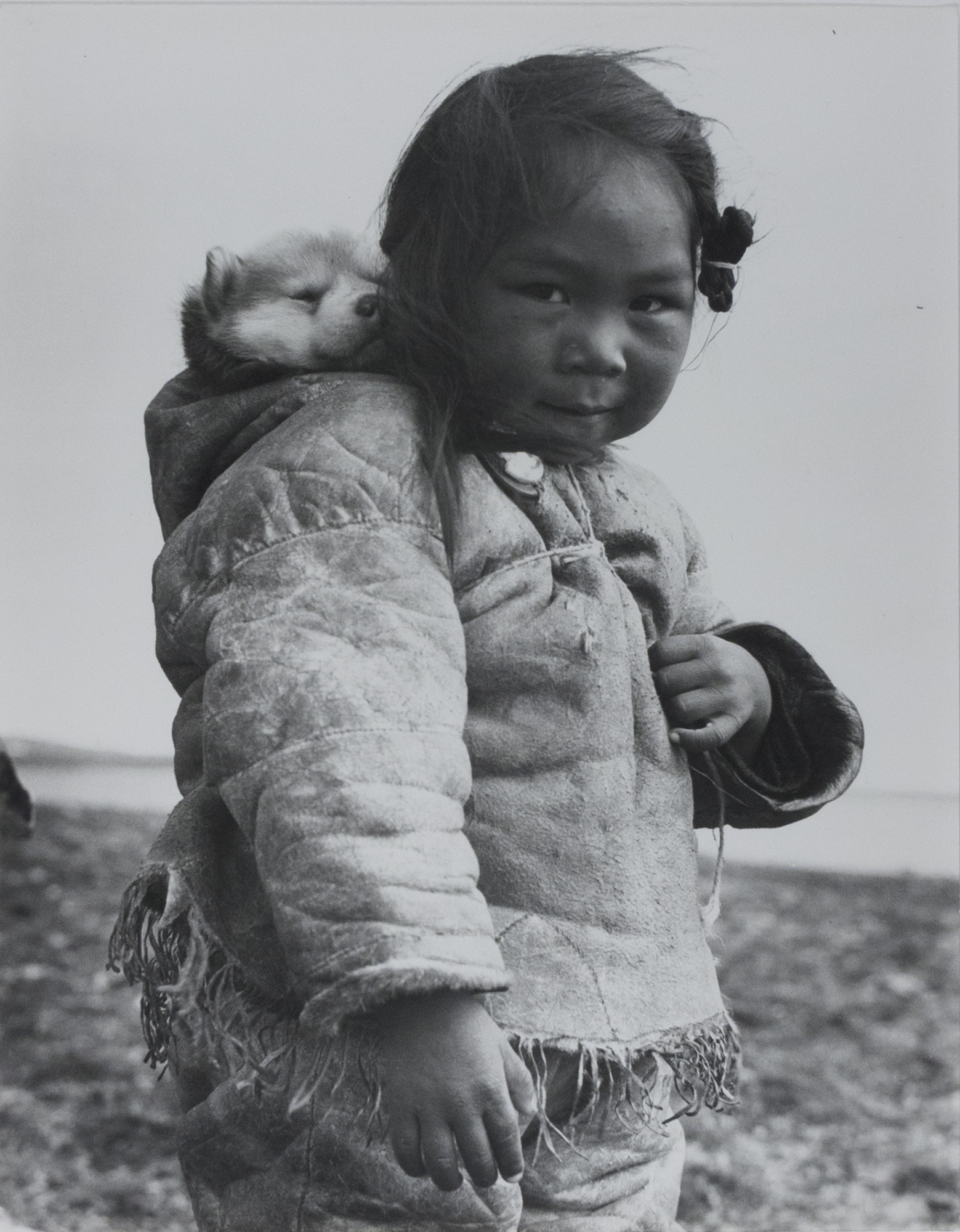

Coppermine, NU illustrates Harrington’s humane touch perfectly. The child shown in the picture is adorable, but then children are supposed to be adorable. We are evolved to feel protective and caring when we see children. When I first looked at the image, I stared into the child’s eye and wondered what became of her. Amusingly, I was so engaged with the child’s expression that I missed the pet. When I did finally notice the dog, a wonderful surprise in itself, the picture became even greater. The desire of children to show off their pets, to create connections through animals is again a universality. We have an intrinsic understanding of the fact that we are all connected. Whether we like it or not, we are all part of the human family. This is not to indulge in sentimentality but to recognise a fact. Coppermine, NU forms a real connection with the viewer and that makes it a powerful photograph.

Our final two images for this article, Padlei, NWTand Untitled [Dog jumping over break in ice], are photographs that I believe meet our preconceptions about what photography of Arctic areas should show. They feature toughness, resilience, and traditional ways of life in challenging icy conditions. This is not to criticise the images in any way; they are outstanding photographs and I think them wonderful. In fact, they recall the more recent work of another of my favourite photographers of the people and traditions of Arctic cultures, previous Look Closer subject Ragnar Axelsson.

Two things strike me when making a modern viewing of these photographs. First, Harrington covered vast distances in multiple solo winter journeys to these remote places using only a dog sled. In our modern age, photographers can be helicoptered in and out of a location. He risked life and limb to make his extraordinary documentary photographs. I find that Harrington’s actions show an extraordinary level of commitment to his craft. Second, the environments featured in the photographs are pristine. They show what our planet is supposed to look like. As I observe these photographs, I wonder if the ice still exists in the places shown in the photographs. In only a short period of time, our activities have caused potentially irreparable harm to these wild realms. They carry a message from our recent past that should inform our future.

The time I have spent with Harrington’s work has led me to draw certain conclusions about him as a photographer. Most importantly, I find a refreshing absence of romantic primitivism in his work. He is a photographer telling a story the way he sees it. Unlike a great deal of other work that features people who live traditional lives, for example Jimmy Nelson’s clumsily titled but technically exceptional Before They Pass Away, the communities that Harrington photographed are not presented as a human spectacle. They are shown because they and the photographer have a story that needs to be told. In addition, I want to see more of Harrington’s work. The pictures I have seen so far are exceptional. He is a documentarian and artist who deserves more of my time and attention. Finally, the Wikipedia page that lists the photographers whose work was featured in The Family of Man neglects to mention Harrington. This is not right. He deserves greater recognition as one of photography’s finest documentarians, and I hope that this article makes a small contribution to achieving this.

This article would not have happened without a chance meeting with Margaret Harrington. It would have been a pleasure to have spoken with her even if it did not lead to this article. Equally, it would not have happened without the kind cooperation of Toronto’s wonderful Stephen Bulger Gallery. I offer all concerned my sincere gratitude.

RICHARD HARRINGTON

Jaffer Bhimji

November 13, 2021 at 20:14

Fascinating story. Thank you Rob Wilson 👏🏻👏🏻

Robert+Wilson

November 14, 2021 at 21:33

My pleasure!

Cary

November 15, 2021 at 01:44

Well told, Rob. His Canada medal suggests more work might be in circulation. Something – a book, documentary – even sponsored by Canada itself would seem appropriate.

Unfortunately its also yet another nick in the mystique of Canada that many Americans have nourished.

Robert+Wilson

November 15, 2021 at 14:17

Hi Cary,

Thank you!

There are a few books of his work out there, but they all seem to be out of print at the moment. I think he is a photographer who deserves a much wider examination that I am able to give here.

All the best,

Rob

Cary

November 15, 2021 at 23:46

It looks like my suggestion of a follow-up, or series of articles within the prescribed length, that might offer more scope for your interest, got dropped from my response (or never made it to the upload stage !).

Robert+Wilson

November 15, 2021 at 23:49

I can’t reveal future plans I am afraid! 😉

James Murray

July 10, 2024 at 16:48

Hi Rob,

I just ran across your article, very nice!

Richard and Margaret were my next door neighbours when I was growing up. We shared a driveway between our houses. I have a signed original print of Padlei, NV, 1950 hanging on my living room wall. It was given to our family as a Christmas gift one year. I also have a signed book of his work.

His first wife Lynn wrote a lot of the text for his books. Sadly she had health issues and passed away.

It is so great to see his work still celebrated.

All the best,

James Murray

Christian Peacock

November 15, 2021 at 18:01

Thank you Rob for exposing us to a greater world of photography. Your insight and point of view is always refreshing to read.

Robert+Wilson

November 16, 2021 at 13:48

Thank you Christian!

Frank Styburski

November 15, 2021 at 18:38

Thanks for the interesting article, Rob.

I think that your writing shows a lot of well deserved fondness for the subject.

Thanks for bringing Richard Harrington’s work to my attention.

Robert+Wilson

November 15, 2021 at 18:39

My pleasure Frank!

Susan Gans

November 20, 2021 at 16:14

Fascinating article and amazing photographs that opened a door to a place and people not known to me. Am glad for your chance meeting and all that followed because of it. Hope you will continue to research and write about Richard Harrington’s work. Thanks!

Robert+Wilson

November 20, 2021 at 16:58

Thank you Susan!

Peter Brand

November 24, 2021 at 05:15

Lovely article Rob. Thank you for highlighting a Canadian photographer that beautifully captured the proud Inuit peoples at a critical time. This little known history needs to be remembered.

Robert+Wilson

November 24, 2021 at 14:01

Thank you Peter!

Gail Orgias

November 25, 2021 at 23:33

So glad you had that chance meeting with Margaret Harrington, and for your recognition and now promotion of these historical & significant photos by her husband Richard. And not only his ‘extraordinary commitment to his craft’ but his intention at the time to alert people to the plight of the Padleimiut people, through his photographs. Your comment resonated that ‘intrinsic understanding of the fact that we are all connected.’ Thank you Rob.

All the best for your own photographic journey

Robert+Wilson

November 26, 2021 at 00:37

Thank very much Gail!

Renate Swerhun

November 26, 2021 at 01:54

In the interesting and educational articles that you write in this space, you reveal your own humanity. Thank you, Rob.

Robert+Wilson

November 26, 2021 at 19:38

Thank you Renate!

Walter Swerhun

November 28, 2021 at 03:08

Well written Bob. Suggest you and May visit the Canadian arctic to see and feel the north country.

Robert+Wilson

November 28, 2021 at 15:21

We would love to!

Cheers!

Enjoy the articl

December 9, 2021 at 01:38

Enjoy the article very much

Robert+Wilson

December 9, 2021 at 15:07

Thank you!

My pleasure!

William Whyard

October 19, 2022 at 01:02

I was searching Richard Harrington and found your atticle. I grew up in Whitehorse and Richard was a friend of my father, an amateur phtographer. I remember several visits to our home in Whiehorse.. My father was a stamp collector so Richard sent postcards from all over the world. He would try to get my fther to go with him to Bora Bora. I’m pretty sure Margaret is his second wife (remarried 1995)His first wife was Lynn Harrington’ a writer, who did the narrative in some of Richard’s books. Anyway I remember the times he visited because he and my father headed out with their cameras and had a ball. Dad always seemed happy when Richard was around but he’d get annoyd when richard refused to talk about his youth. I’m holding a photo Richard sent to my mother {my father having died} from Dec4, 2001 when he got his Order of Canada his note on the back says “Bowed and humbled in front off Her Majesty’srepresentative.” Tough little guy… anyone who has been in extreme cold weather can appreciate the photos he took in the NWT in the late forties. It’s hard on the camera as well as the photographer. Thanks for doing the writeup.

Rob Wilson

October 20, 2022 at 15:19

Hi William,

You are right – Margaret was his second wife, and a lovely lady to talk to as well!

Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts. It’s lovely to hear from someone who actually knew the man.

All the best!

Rob

Linda Crooks

February 1, 2023 at 23:18

I worked with East York Community Care services and started out helping Mr Harrington wife .Later after her passing I was his caregiver and PSW. It was a pleasure working with him and helping him out and he gave me a copy of the picture of the eskimo woman and her child and I still have it till this day too.I was saddened to see the write up in the Toronto Star Paper of his Passing and clipped it out have it today also …….A great man that Canada should be proud of

Rob Wilson

February 2, 2023 at 15:54

Absolutely. It makes me really happy to hear from people that knew him and that he was a good man.

Thank you!

Tracy Byers Reid

June 12, 2023 at 22:46

Hello Rob,

Thank you for sharing your information. I bumped into your article while researching Project Naming, of which Richard Harrington’s images are a part. I thought it might interest you to see that his work included in this project, beginning with 500 of his images being the first digitized in 2002. I have found the archive record for 3 of the 4 images you posted (see below), which provide information on the subjects, including the name of the little girl in the photo with her pup.

(I have no affiliation to Library and Archives, I am researching Project Naming as part of Master’s coursework.)

Thanks!

Image 1: https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=3192210

Image 2:https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=3194003

Image 4: https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=3193793

Info on the Naming Project:

https://thediscoverblog.com/2015/05/28/project-naming-is-expanding/

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/inuit/020018-1304-e.html

https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/project-naming-public-asked-to-id-unknown-inuit-aboriginals-in-12-000-images-1.2397167/comments-7.646067

Rob Wilson

September 5, 2023 at 17:39

Great stuff!

Thank you for sharing!

James Middleton

September 1, 2023 at 14:00

Passion an fire in the belly I get you

Rob Wilson

September 5, 2023 at 17:40

Definitely!

Susan Lambert

January 16, 2024 at 18:22

Thank you for this article Rob. I have recently come across the extraordinary book Padlei Diaries, 1950 edited by Edmund Snow Carpenter. I found this book on a shelf in our local library. I initially was annoyed, someone had.displayed it upside down! I went to correct the placement but was stymied to find that neither the from or back covers contained anything. And that was just the first mystery. are you still working in this area?