In the late Carlos Ruiz Zafrón’s marvellous modern gothic novel The Shadow of the Wind, which is set in a post-civil war Barcelona, the protagonist, Daniel, is taken by his father to a place known as The Cemetery of Forgotten Books, a library which is home to books that have been either suppressed or simply forgotten about. Here, Daniel discovers, takes, and falls in love with a novel entitled The Shadow of the Wind by a mysterious and largely forgotten author named Julien Carax. This is the starting point of a novel filled with mystery, intrigue, romance, and tragedy. I will say no more about it beyond recommending it to you, dear reader.

The idea of there existing a place where books go to fade into oblivion, but where the chance discovery of something magical can be made, is a compelling one, and it is one that led me to consider if the same could be true for photography. Is there somewhere where I can discover obscure yet brilliant photographers whose inspiring work has faded into obscurity?

I have made discoveries before. In some random article that has long since slipped my mind, I read some praise for Paul Graham and his book A Shimmer of Possibility. Being a curious student of photography, I immediately made efforts to find images from the book. This inevitably led to a purchase. The work opened my eyes to a whole new world of narrative photography. Graham’s project was unlike anything I had ever seen before.

Yet, as lovely as it was to discover Graham’s work, it does not really fit the bill for what I want to discuss in this article. Here is why. One of my dear nieces, in this case nine-year-old Amy, recently made her own new musical discovery and is now a huge fan of The Clash. My sister and brother-in-law, as well as Amy’s older sister, get to enjoy the youngest member of the family spending half the day walking around the house singing “I fought the law and the law won” on constant repeat. This is quite similar to my discovery of Graham. The work was already well known, but neither Amy nor I were aware. You can ask my wife if I have spent any time wandering around our apartment holding my (signed) copy of The Whiteness of the Whale shouting about how everyone should look at the pictures. I am saying nothing more on the matter.

My reflection upon the premise of Ruiz Zafron’s book led me to a happy realisation – such places do exist. There are multiple places where great photography is housed and where otherwise beautiful work can fade into obscurity. These are some of the world’s great photography collections: the Library of Congress, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the New York Public Library as well as others that include the International Centre for Photography (ICP) and the George Eastman Museum. This realisation compelled me to set myself a challenge: find some wonderful work by some largely or even totally forgotten photographers and share it in this article.

I must stress that although I am sharing the images and names that I found, this is not really my point. You might not find these photographs anything like as interesting as I do. You may not have any desire at all to seek out the photographers that I discovered. I can certainly understand if this is the case. The photography that each of us enjoys is an incredibly subjective and personal thing. That the craft is fully able to respond to and fulfil our individual longings is another of the medium’s great strengths. My objective is to encourage you to go and undertaken a similar treasure hunt. There are more spots out there hiding buried treasure chests filled with photographic gold than even Long John Silver could dig up in a lifetime.

For my excavation, I tried to place some constraints on myself for this task. Not only should the photographer be unknown to me, but they should also be largely unknown to anyone who is likely to read this article. The work should be in the public domain as I have no time or budget for securing image rights. Most of all though, the work should be fascinating. As you will see, these requirements were more difficult to fulfil than I expected.

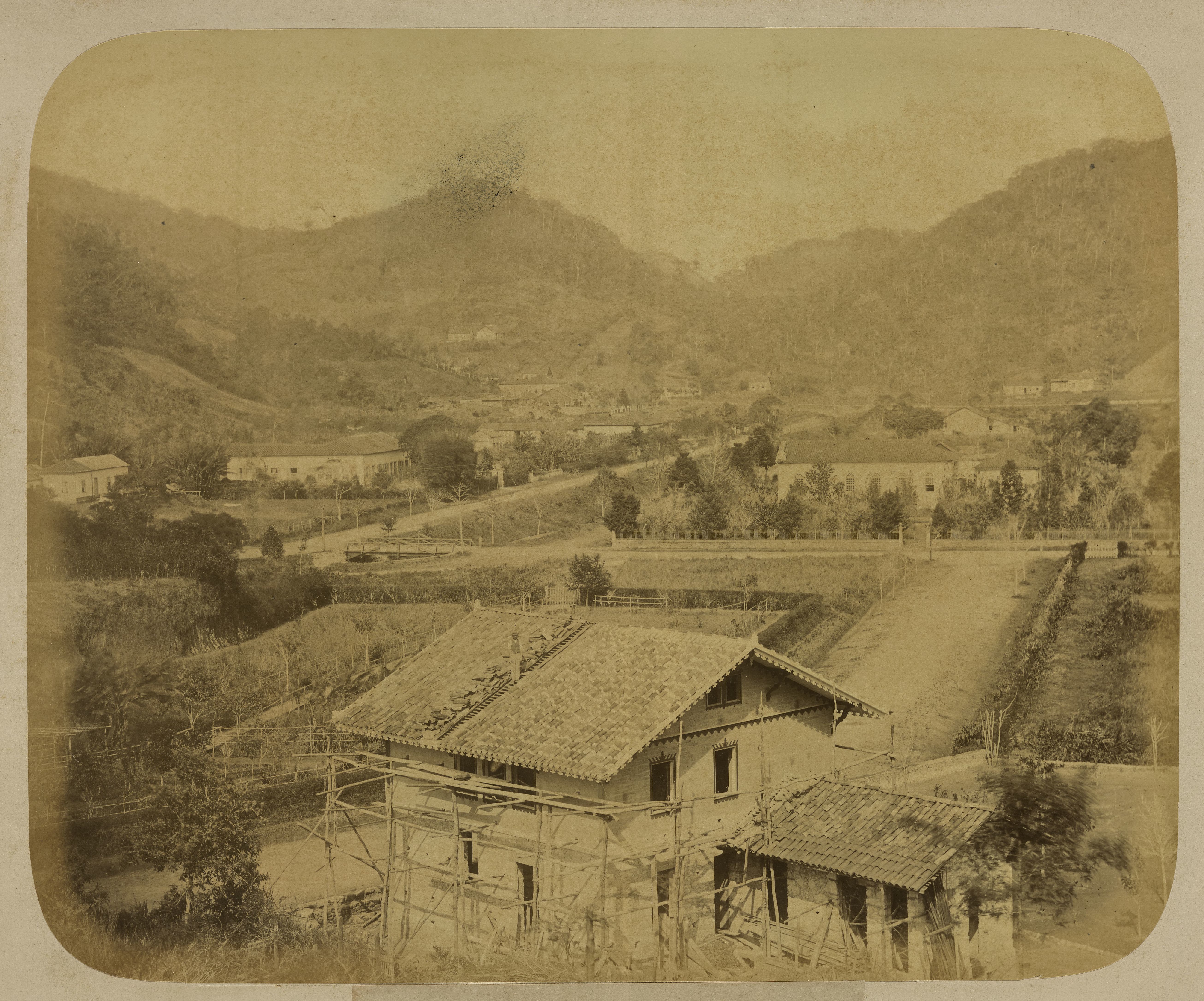

I decided to start in the Library of Congress and half an hour of playing around with search terms, I came across the work of Pedro Hees. He was born Philip Peter Hees in Germany in 1841. However, in 1845, his family relocated to Brazil. During the 1860s, he took up photography and became successful. He was mostly known as a portrait photographer and made images of Brazil’s royal family. He married young but only lived to thirty-nine. During their marriage, Hees and his wife produced an extraordinary eleven children. There is little information about his work that is easily accessible on the internet. I found a couple of Brazilian sources that provided the information I have included here.

The work that I found is from Hees’s most well-known collection – an album called Views of Petrópolis. The album, which can be found in its entirety in the Library of Congress’s collection, contains fifteen photographs showing the city. These photographs not only take us to the early years of photography but show a land that we, as modern observers, rarely encounter when delving into the medium’s history. We see uncountable views of Europe and North America, but other places are rarer. Looking back into Brazil’s photographic past is a treat.

Hees is not the only interesting photographer that seems to meet the criteria for my challenge that I have found in the Library of Congress archives. On a previous “expedition” for a Digial Companion article, I came across the collected works of Arthur Genthe. Genthe was active in San Francisco in the early 20th century. He is well enough remembered to have a Wikipedia page devoted to him, but I suspect his name does not spring readily to mind when thinking of American photographers of the early 20th century, so I think that I am not pushing things too much by including him here.

Genthe’s colletion contains a large quantity of autochromes. This remarkable early colour process, which used grains of potato starch in its execution, is one that I have a huge affection for. Some day, if it is still possible, I will attempt the process for myself. The image I have included here features the one and only Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. It is a joy and a wonder to look upon the face of such an important cultural figure in colour.

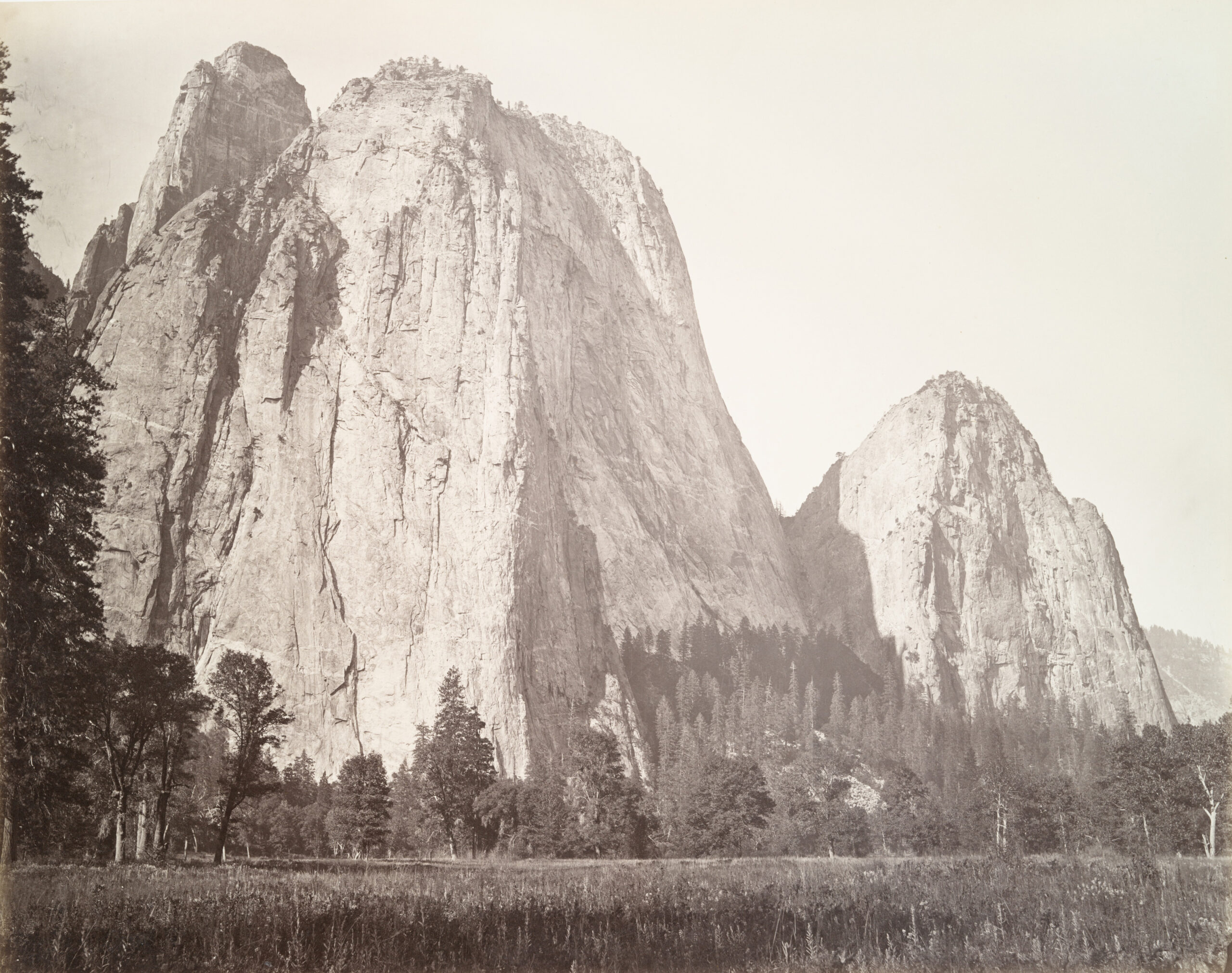

From the Library of Congress, I turned to the New York Public Library’s digital collection, and the lovely collection in the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Almost immediately I found a magical series of images of Yosemite National Park. The immediate assumption was that I had located a fully stocked pharaoh’s tomb of photographs. The pictures were amazing. Yet, in my haste and desire to enjoy this gold, I neglected to pay any attention to who the photographer was. I just assumed that as I did not recognise the images, it would be someone unknown to me and probably unknown in general. Assumption is, of course, the mother of all eff-ups. The photographer was Carleton Watkins, a photographer that I not only am I well aware of (although hindsight suggests not well enough), but one that I have previously written about in this very column!

Despite utterly ignoring my own rules, how could I not feature my favourite of the images I found? Cathedral Rock, Yosemite is just a lovely photograph. It recalls a fresh spring morning under a pristine blue sky. Birds are singing and I am about to begin a hike through the forest towards the rock. It is everything I want from an historic landscape photograph, so I make no apologies for its inclusion.

My last stop on my tour of these wonderful repositories of the little known, almost forgotten, and completely forgotten was the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Its collections are every bit as fascinating and seductive as those from its American counterparts. However, the images themselves are far less easily available for publication. Many images, some well over one hundred years old, are still for sale under license. Others, whilst freely available for download, are subject to far more onerous terms of use than those at the Library of Congress or New York Public Library who have both placed their images in the public domain. These terms make the publication of their collection here unrealistic. This is a crying shame. The idea of extracting money to feature a one-hundred-year-old photograph is one I find quite absurd.

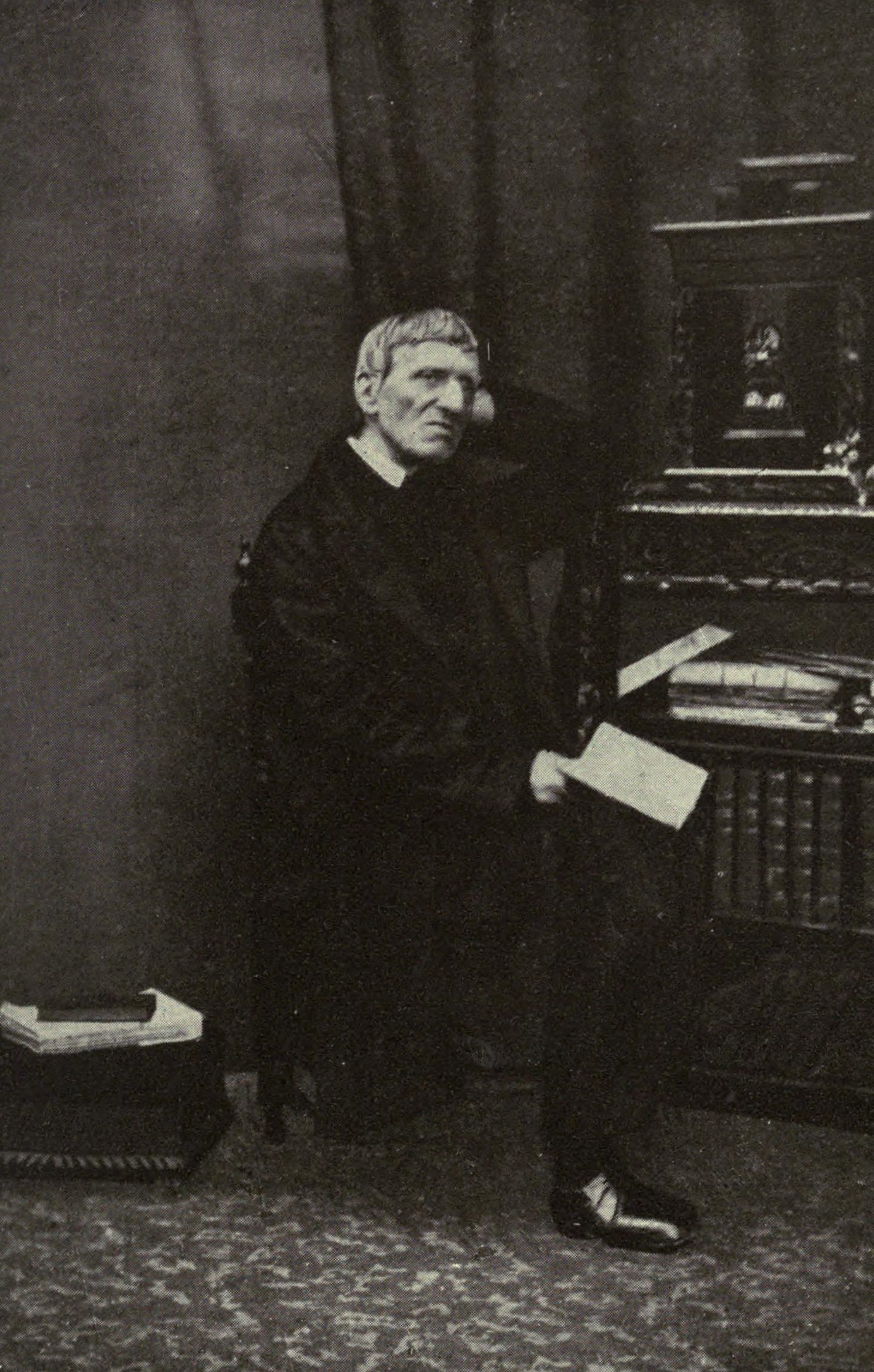

Still, this should not stop you from visiting. The collections pages are filled with brilliant photographs by the likes of William Eggleston, Francis Frith, Julia Margaret Cameron, and so many more. Many other photographers fit my task’s original requirements perfectly, and it was here that I discovered the photographer who fit the criteria for this article perhaps best of all. Have you heard of Adolphe Beau? Nope, me neither. Yet, his portraits of Britain’s 19th century public figures are brilliant and well worth your time.

I can find no biographical information on Beau, but if any reader can, I would be happy to hear from you. Thankfully, there are plenty of examples of his photography. The one I have included here does not come from the Victoria and Albert Collection (due to their licensing restrictions), but from Wikipedia Commons. I was able to locate this photograph of John Henry Newman who was more commonly known by his title of Cardinal Newman. Newman was an influential but controversial figure in the mid-19th century. I am not sure if this is Beau’s strongest work, but it portrays Newman as a serious, contemplative, and perhaps rather grumpy individual. There are other portraits, particularly paintings, that show him as a rather gentler looking figure. One wonders if that represents him fairly. Still, I am happy to have an image to share with you.

The research for this article was a lot of fun to conduct. Finding the work of Hees and Beau was a genuinely joyful surprise. What is so lovely to contemplate is the fact there is so much more out there waiting to be found. The collections of the three institutions that I rummaged around in are vast treasure vaults for anyone interested in doing something similar. Why don’t you have a go yourself? You might not discover a new Vivian Maier, but there is plenty more visual treasure for you to dig up. I would love to know who and what you have found!

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM