Bernard Moncet’s family knew that there was a stack of old glass plate negatives in the attic of his wife’s grandfather’s old home, but nobody had ever been inclined to do anything about them. They had lain there untouched and gathering dust for the best part of seventy years. Surely, if there was anything interesting on them, someone else in the family would have done something about them years ago, but nobody had. So, there they continued to sit, awaiting their moment of rediscovery.

In 2020, it was time for Bernard’s “Howard Carter” moment. His son needed a home and his great-grandfather’s old house was perfect but needed renovation. It was during these renovations that Bernard, rummaging around in the attic, found the long-ignored plates. Although his discovery was not a three-thousand-year-old tomb, Bernard, like Carter, still found “wonderful things”: beautifully composed images from the early twentieth century. The pictures turned out to be a remarkable historic treasure trove, documenting rural French life before and after the horrors of the First World War. Extraordinarily, the plates had never been printed, not even by the photographer himself.

From the moment he examined the first few plates, Bernard knew he was onto something special. Bernard, a talented photographer in his own right, recognised that these were not ordinary snapshots, but the work of an exceptionally fine image maker. We can only imagine his excitement as he blew the dust away and lifted the first plate to the light. In his own words, he felt “like a child who thinks he has discovered a treasure”.

Who was this photographer? He was the former owner of the house and Bernard’s wife’s grandfather, Casimir Bessiere. Casimir was born at the end of the 19th century in Espalion, a small village in the south of France. He took up photography at an early age, but it was never his profession. He was a carpenter by trade. In his youth, he bought a used camera that served him until he was finished with photography. His early photography practice was soon curtailed because in 1914, at the age of twenty-three, he was conscripted into the French army. He served throughout the war and was wounded three times. After being demobilised in 1919, Casimir and his wife moved to Bresse in eastern France. This allowed him to return to photography and over the next few years he photographed his neighbours and friends. His photography career was brought to an abrupt and premature end by the outbreak of the Second World War. After the war’s conclusion, Casimir never brought the camera out again.

After the wonderful discovery, the hard work began. Bernard initially tried to scan the plates, but this failed. The scans had none of the clarity of the plates and much of the details in the greys were lost. Another approach was required, and Bernard hit upon a moment of inspiration: using his iPad as a backlight. After placing the plates on the iPad, Bernard was able to photograph the images cleanly. Post-processing enabled accurate adjustments to tone, contrast, brightness, and exposure. This clever approach allowed Bernard to produce these wonderful images that I am overjoyed to present here today.

The photographs are delightful. They are humane, good-hearted, funny, and beautifully taken. Looking upon them, except for one image, fills me with elation at the wonder of our shared humanity. These people are not dead in the ground to me but alive. In the film The Dig, Basil Brown, or rather Ralph Fiennes as Basil Brown, the great self-taught archaeologist, sums up the experience of looking at these photographs perfectly, “From the first human handprint on a cave wall, we’re part of something continuous. So we don’t really die.”

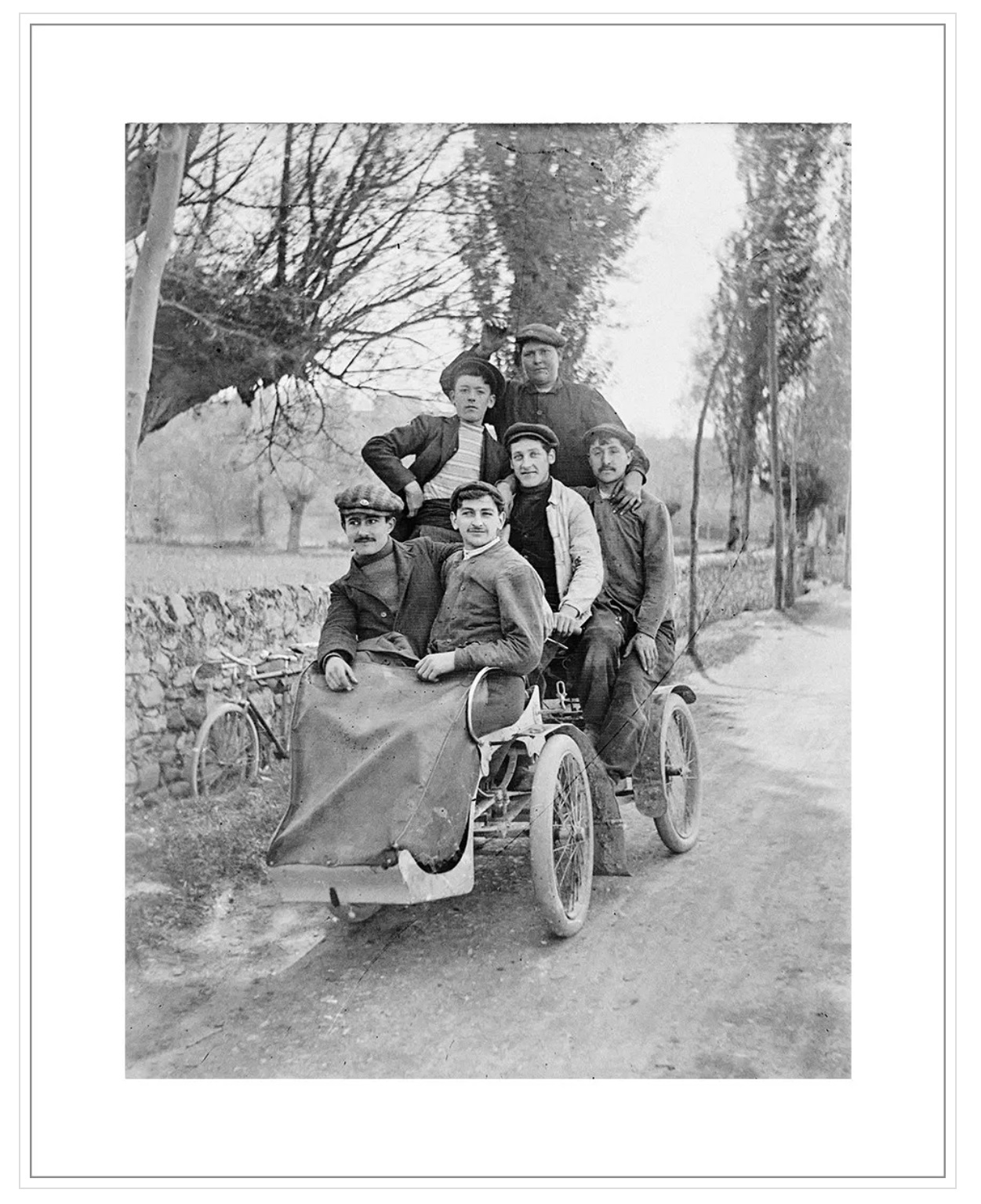

However, I make an exception of one: our banner image. This is not because it is a bad image, far from it. It is not because it is not humane. It is just like the rest, but this image disturbs me. It is the photograph of a group of fourteen young men. Thirteen of them sit on a carriage, the other on a lead horse. Some of them, particularly the row of four second from the back, appear little more than boys. As Bernard understands it, this image was taken just before the First World War.

It is the knowledge of what comes next that creates the disquiet. This is no longer a jolly picture of young men with the world in front of them. It is an image of men about to be embroiled in the most horrific of conflicts. We can only wonder at how many of them met their end among the horrors of Verdun. This photograph is haunted by four and a half years where imperial hubris met its own brutal mechanised nemesis.

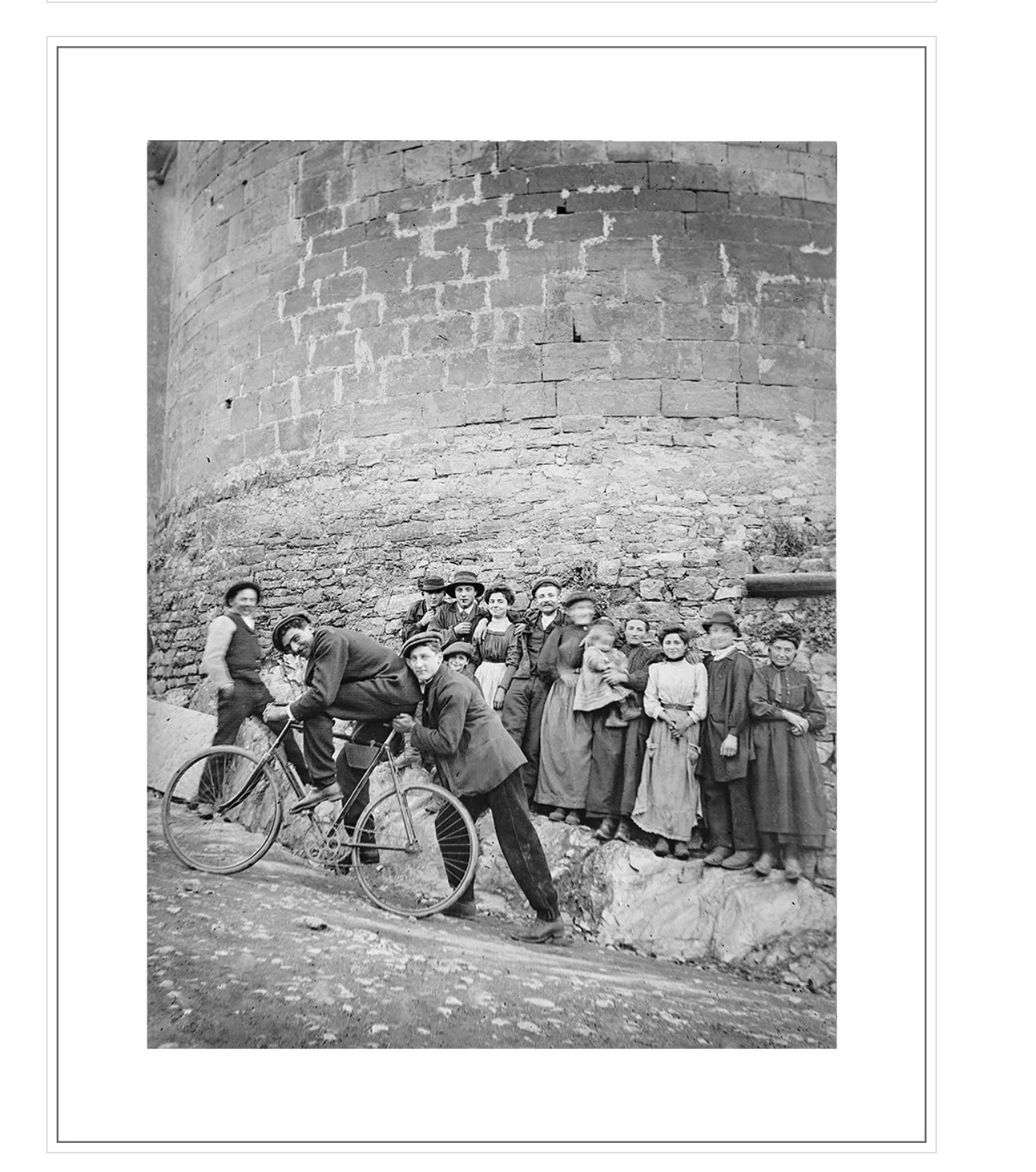

The photograph that brings me the most pleasure shows a cyclist being pushed up a hill. Everyone in it seems to be part of the fun. It is a funny and joyous image which illustrates what a magical thing photography must have been in its early years. Our age of ubiquitous photographic images is a long way off for these people.

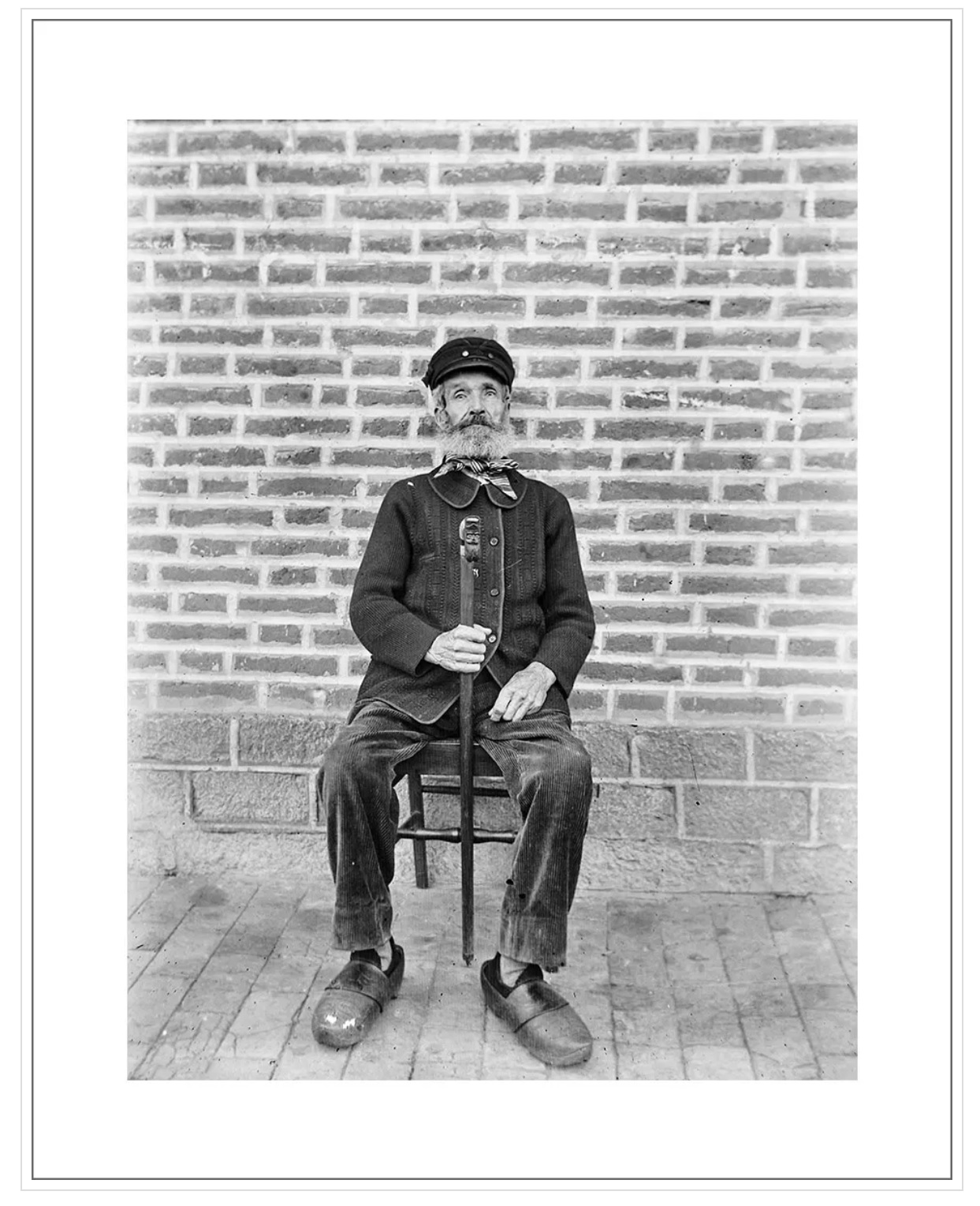

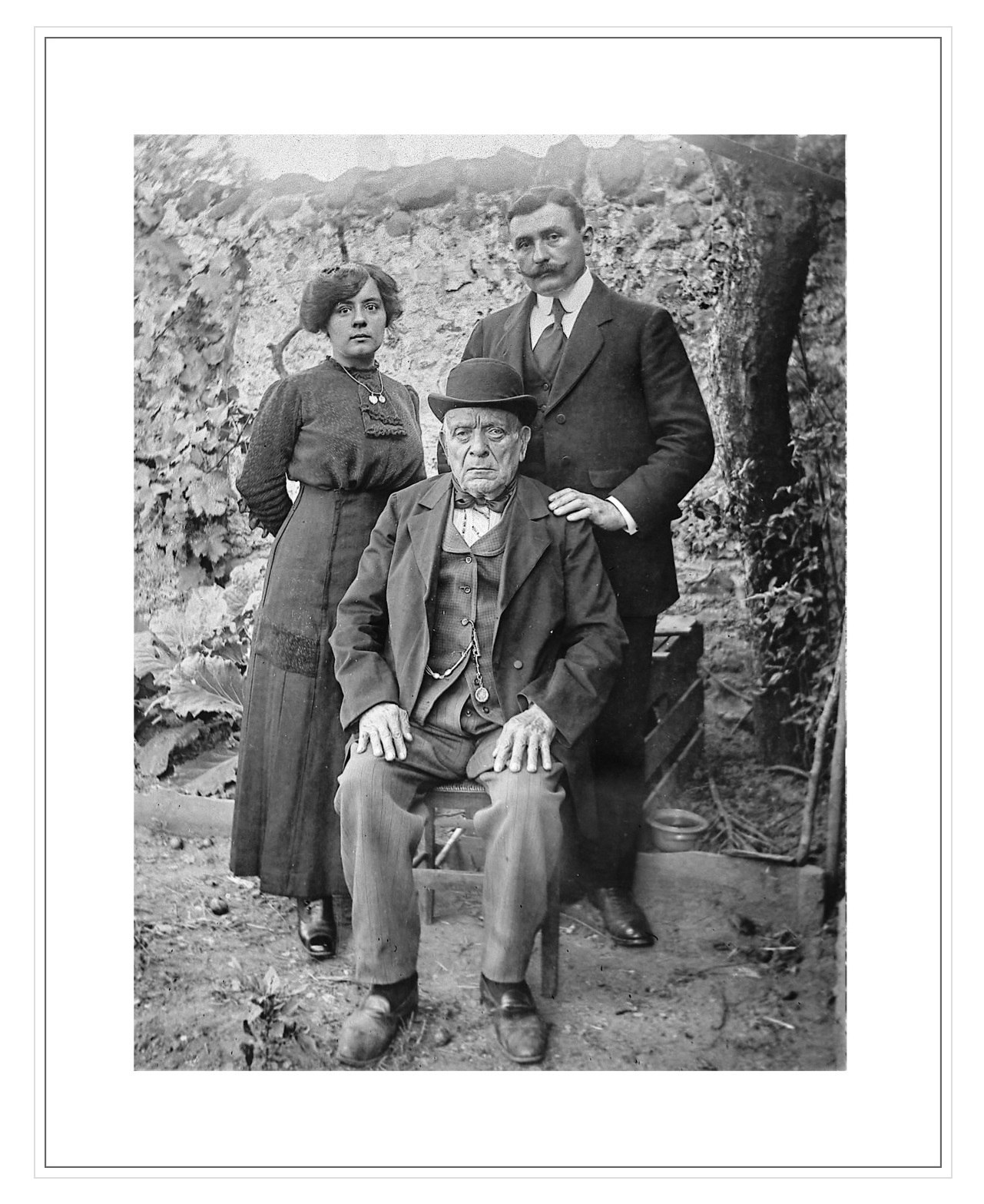

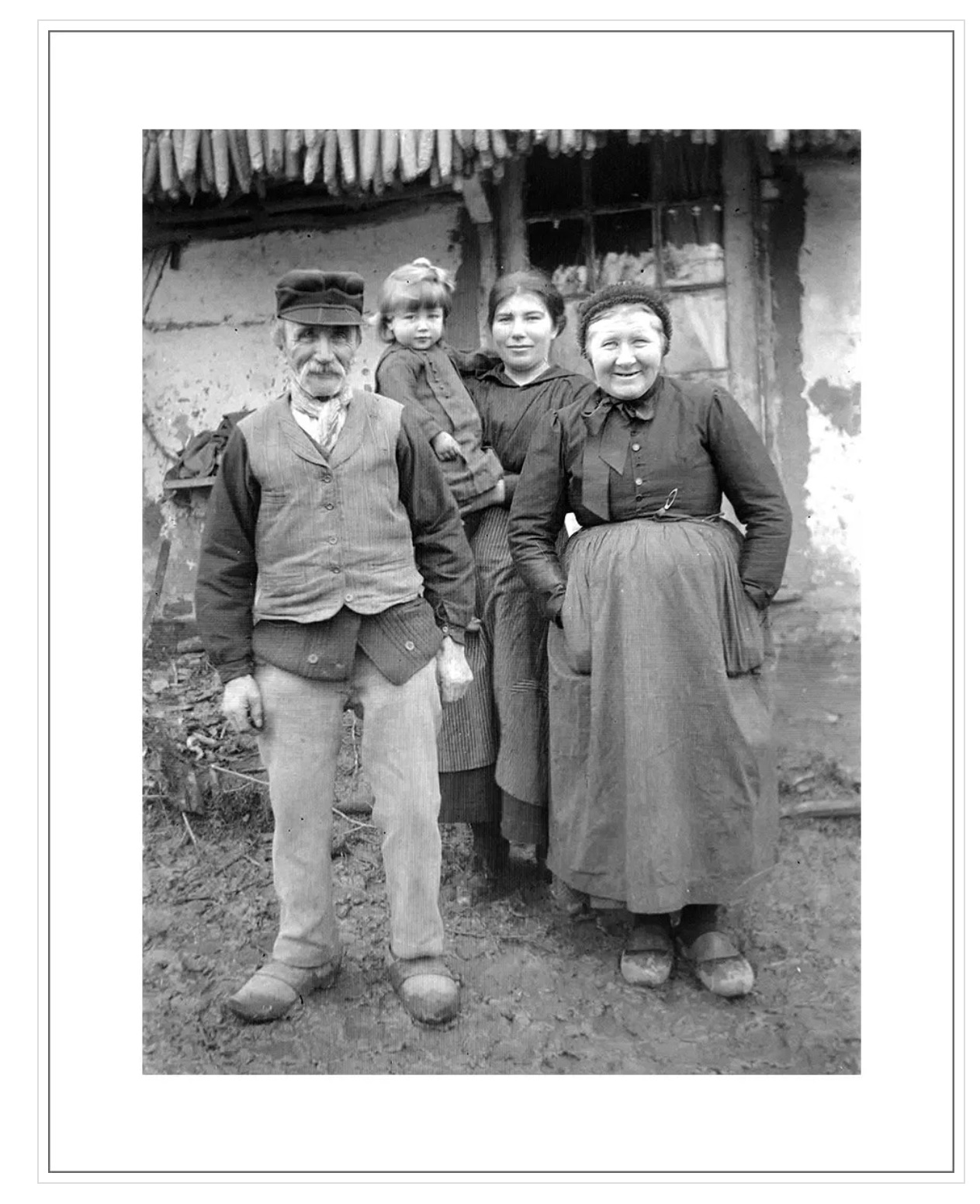

The other images are all beautifully composed portraits. From the formal family shot of two adults standing behind a seated old man to the informal, chuckling grandparents standing in front of who I assume to be their daughter and grandchild, all are wonderfully humanistic. They all feature elements which bring Casimir’s world back to life: the hats, the shoes, the extraordinary handlebar moustaches, the canes, the cars, and the carriages. People, rich and poor alike, are alive in these images.

Casimir Bessiere is a name that would have been entirely lost to the history of photography without a lucky discovery in an old attic. Bernard’s work in reproducing these images has illuminated a world unlike our modern age and transported me there. I love these photographs enough that I hope to see Casimir’s work published in a book in the future. It is one I would surely buy. Researching and writing this article has been a genuine joy. I hope these pictures illicit the same response from you.

More of Casimir’s work as well as Bernard’s own photography can be found at https://www.bernardmoncet.fr/.

Joseph

February 13, 2021 at 19:12

Truly remarkable find! Images are exquisite and timeless. I consider myself fortunate to see Casimir’s photographic captures. Thank you so much for finding and sharing.

Robert Wilson

February 14, 2021 at 15:11

You are most welcome!

Tom Wilson

February 19, 2021 at 14:49

These remarkable photographs are refreshing in their purity and honesty, and I am truly inspired by the work that you’ve done to bring them to our attention. Thank you.

Robert Wilson

February 19, 2021 at 17:47

It is very much my pleasure Tom!

Thank you.

Ines

March 17, 2021 at 20:13

Beautiful photographs. Makes me wonder what will happen in a hundred years ahead when our grand grandchildren find a memory card from today. Will they be able to see the content ? Or will they ever know what a sd card is ? Perhaps not and they will throw it as garbage….