Here is a proposition:

Memory demands the present.

At one level this is obvious. Memory, by definition, resides in the previous, in the past, in the already-happened. But I’m not talking about simple data. Where did I leave my keys? Oh, they’re over there. I’m talking about the memories we carry, quietly, secret sometimes even to ourselves, through every day. I’m talking about how memory makes us feel. Memory has emotional, spiritual, sometimes soul-lifting and sometimes soul-crushing weight.

“The Boys” by Rick Schatzberg

Published by powerHouse Books, 2020

review by W. Scott Olsen

And I am being intentional when I use the word “demands.” The past is a constant judge of our present. Yes, I could call it a lens or a filter, and that would be somewhat right. But there is more to it. Standing in whatever today may be, we open a drawer and take out an old photograph of ourselves. Yes, part of us looks at the image and wonders, from present to past, who in the world are you? More importantly – we feel this in our gut – the photograph asks the same question, from past to present. Who in the world are you?

Memory demands an answer.

Think Mnemosyne, daughter of heaven and earth, mother of Zeus. Think Lord Ganesha, seated between the higher and lower chakras, the god of wisdom.

Better yet, think Tevye and Golde in Fiddler on the Roof, at the wedding of their daughter.

Sunrise sunset, sunrise, sunset!

Swiftly fly the years,

One season following another,

Laden with happiness and tears…

More than anything, looking at that old photograph, we feel the size of the space between then and now. I’m not talking about years. We feel the loss. Mortality is just a little clearer. But with loss comes wisdom and, with any luck, grace.

I mention all this because of The Boys. The Boys is a genius book, profoundly moving in the way it holds up past and present simultaneously and lets us consider them both in the same moment.

As the book’s promotional material says:

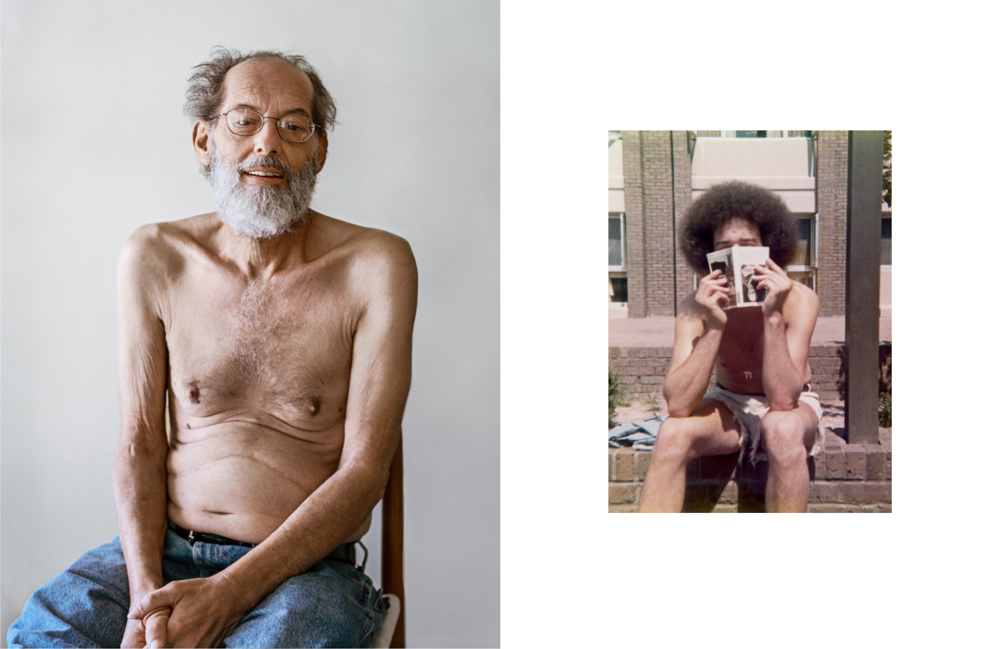

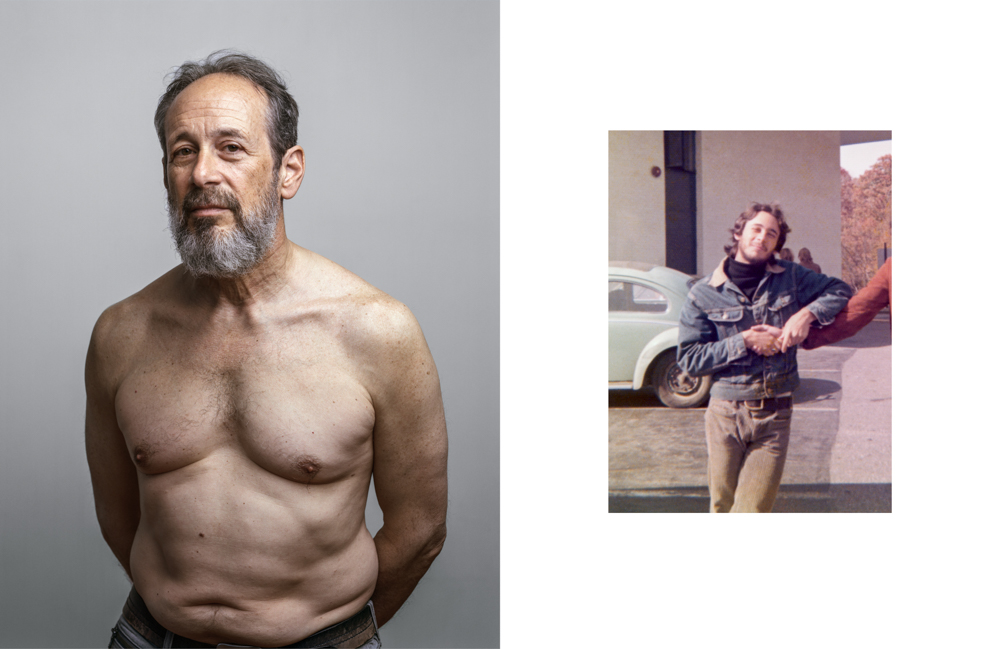

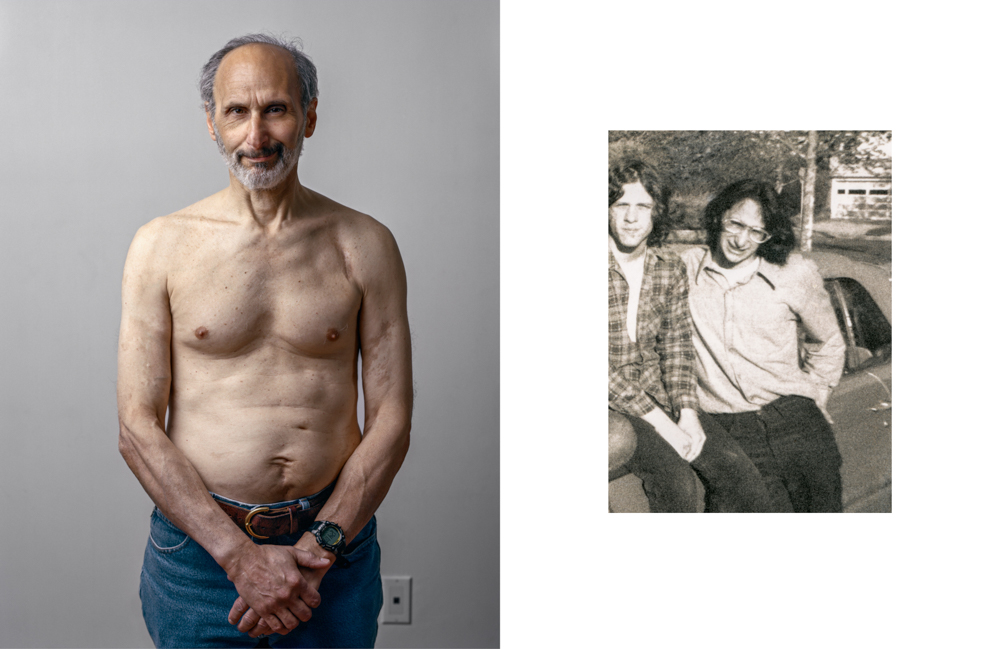

When two old friends died unexpectedly, Rick Schatzberg spent the next two years photographing the remaining group of a dozen men. Now in their 67th year, they have been close since early childhood. Schatzberg collected vintage photos that tell the story of this shared history and uses them to introduce each individual as they are today. These are paired with large-format portraits which connect the boy to the man. Mixing in text with these images, Schatzberg depicts friendship, aging, loss, and memory as the group arrives at the threshold of old age.

Simply put, as his childhood friends began to pass away, Schatzberg digs out the old photographs, the Instamatic shots, the casual, accidental, hell-why-not shots. We see 70s hair and clothes. We see unposed attitude and personality. We see teasing and goofing off. We see a group of friends in the act of being friends. I don’t know any of the people in these images, but I am about the same age and I have thousands of 4×6 prints in various drawers that are essentially the same. I feel like I know every one of them well. Set alongside the old pictures are new ones: intentional, large format portraits. The portraits are intimate. More often than not, the men are seated, their shirts off. This isn’t muscular boasting. These images are the truth of bodily aging.

The images from the 70s are exactly what you expect them to be. They are fun. The new portraits are excellent. The juxtaposition of old and new is insightful. However, The Boys is also filled with poignant, literary, eloquent and heart-felt writing. Each bit of writing is a small narrative, a remembrance. This is important. Each bit of writing is told from the point of view of today, looking back at a past that is asking. For example, the book begins this way:

Last year Eddie died of a heart attack. A death as random as a lightning strike, that makes you think there but for the grace of god…. Jon died nine months later from an overdose, an end that seemed inevitable and makes you think the grace of god is questionable at best. This fragile symmetry is not lost on us, my friends and me, though we’re less likely to discuss it than to raise a glass in their memory. Tell a story or two. Laugh.

Eddie’s ashes sit in an urn, a tin really, in Z’s bedroom in Florida. Jon lies buried in Rochester, in a family plot. Their silence is equal but I hear their voices. The rest of our tribe go about their business, each of us holding personal traumas and losses close to the vest. We bear the indignities of aging stubbornly, a catalogue of maladies that come with the territory.

As I observe my friends I detect an unpredictable shift in spirit that appears at the threshold of old age. Small compulsions are amplified in proportion to a world grown stranger. We measure patterns of the past. We survey a new landscape where the companions of our youth grow fewer and more precious. Humor is our antidote; when we’re together we’re still a bunch of stand-up comics.

Privately, we explore a deeper intensity.

And at the risk of quoting too much, this is how the book ends.

Coda

Soon after our New Year’s gathering, Brad died. His health had been failing and he said he felt too ill to make the drive. No one knew how sick he really was. Six weeks later, Fred died of a heart attack on his 65th birthday. We saw him for the last time at Brad’s memorial dinner.

We think we’re all in this together, but the winnowing advances one by one.

As with Jon and Eddie, I see Brad and Fred more vividly now, my thoughts focused like images resolving on the camera’s ground glass. This sudden clarity surprises me. As petty judgements fall away, what’s left is love.

Actually, that’s not how the book ends. One of the most remarkable things about The Boys is an essay by Rick Moody, an American writer best known for The Ice Storm, at the end, after the Coda. Moody’s essay is a consideration of time and image and a deep note for the ideas of this book as it concludes. He writes:

“…photos of creaky, decaying, older white men struggling for dignity are perhaps the hardest photos to look at now. There is no audience, in the strictest sense, for these images, if audience is determined by fashion or by the merchandising demographics of the present.

But that’s exactly what makes this book terribly affecting. The relationship of Schatzberg’s gaze to his subjects is never less than loving, never less than intimate, but it is also, fair to say, remorseless. In this, I think, the book tells us a lot about how one thinks about one’s own past.”

Again according to the book’s promotional material: “Rick Schatzberg is a photographer and writer living in Brooklyn, New York and Norfolk, Connecticut. He received his MFA in Photography from the University of Hartford in 2018. His first monograph, Twenty Two North (self-published), was awarded first prize at Australia’s Ballarat Foto International Biennale.”

I don’t know any of the people in The Boys. I know all of them well. All of us reach a point where age becomes wisdom and happiness and remorse and pain and love. Those aren’t contradictions. Age is all of those things at the same time. Old photographs placed against new ones can make this clear.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.