Sometimes a simple idea is the best idea. Sometimes, in fact, a simple idea can be genius.

Every Wednesday night, at 10:43 p.m., Wooter Vanhees boards a motor scooter and goes looking for insight. “That’s the moment when the stars of work, family, and personal time align,” he says. “That’s when I take my trusty old scooter and head into the city.”

“Hà Nội”, by Wouter Vanhees

Published by Matca, 2020

review by W. Scott Olsen

Vanhees lives in Hanoi, Vietnam. Yet he is a long way from native. Born in Belgium in 1978, he’s been based in Hanoi only since 2015. But he calls Hanoi his adopted city and his new book, Hà Nội, is a wonderful exploration of a place in the process of transformation. The book is a nocturnal dive into the place he wants to call home.

“Hanoi is shedding its skin,” he writes in a one-page preface. “So what to make of its spirit?”

Vanhees’s book asks for, and rewards, close inspection. A city at night is dark, unpopulated, a collection of muted colors and building angles. No crowds. No wrinkled faces. There is nothing of the immediate drama of street photography. There is no poignancy of a portrait. However, at night, there are other revelations.

The images, every one of them, are layered, both in terms of composition and insight. In one, a large building—what I assume are apartments—with garish white lights on top, bright vertical and horizontal lights forming lines on the façade, silhouette a telephone and power pole, which itself rests behind a collection of clay pots, some overturned, some upright, at least one with a plant inside, though it’s tough to tell if the plant is living or dead. The lines attached to the pole run in two directions, one at a right angle to the other. The top half of the image is all impersonal modernity, straight lines and cold tones. The bottom half is all soft and round shapes, stories of living things told in warm tones. The pole is a transition space. The problem is that the bottom half of this image looks like a wasteland. There is sadness here, a nostalgia for former values.

I spent twenty minutes admiring just this one image.

“I want to understand this city,” he writes. “There’s order in its chaos. There’s stillness in its noise. There are so many shades to its darkness. And it’s changing so fast. Houses, alleys, and entire wards disappear, with towers, streets, and new urban areas taking their place. It’s hard to come to grips with this transformation, not understanding what was in the first place, let alone what is to come.”

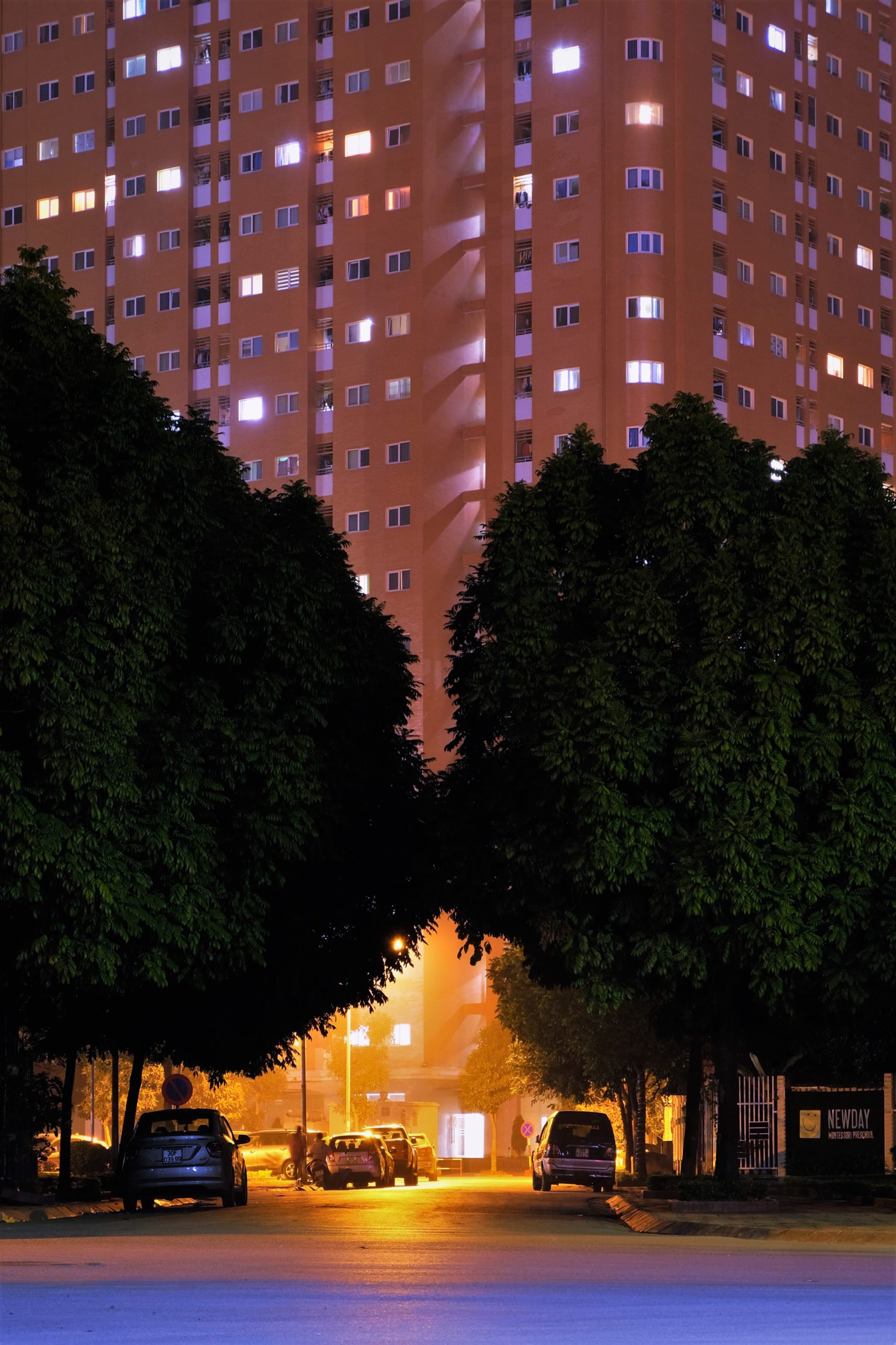

In another image, a large apartment tower sets the background and trees provide a canopy for the street leading up to it. But in the image, the trees obscure a streetlight and the result is a complete change of mood between the building and the street. The street looks warm and intimate in an orange glow. If you look very closely, you can see people, just two, walking. Again, there is that tension between impersonal and personal. The transition is a forest (so to speak). Though, to be complete, every lighted window in the apartment building hints at individual lives.

In her own brief Introduction, Vietnamese photographer and coordinator of Matca, Hà Đào writes: “Sites of memory might be inevitably lost to new layers of concrete and steel. But nothing disappears completely. A certain tenderness persists, though elusively, lurking somewhere in a winding alley, a stone bench, an organic shape of a shadow—minuscule details that disturb the uniformity of the exterior. But one has to look long and hard.”

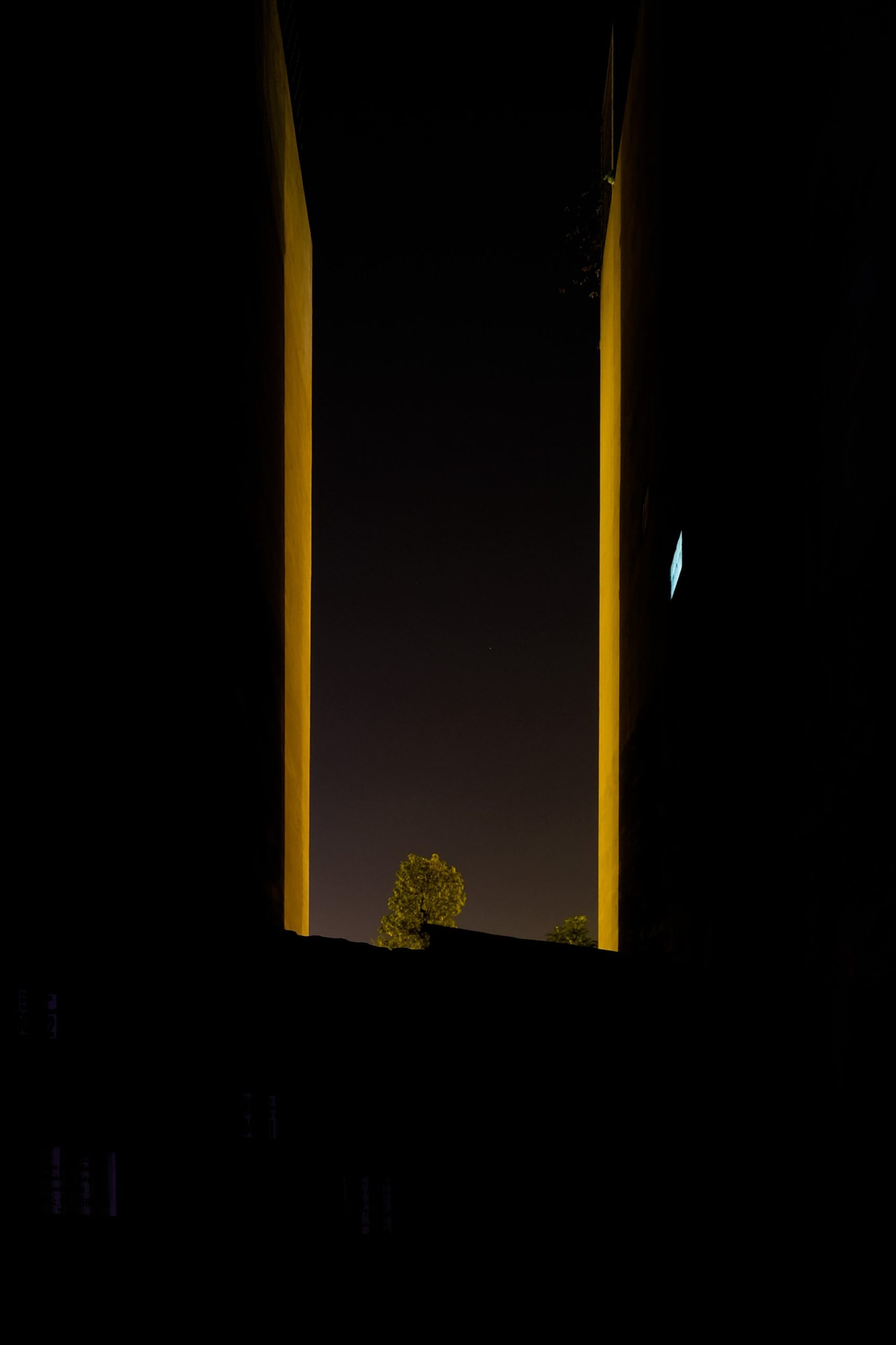

Many of the images in Hà Nội are studies in shape and light. There are building corners, remarkable colors, contrasting if not competing shapes. As formalist expressions, they deserve to be hung in galleries. One of my favorites is an image of a tree in an opening between two buildings. (I think they are buildings, these are night shots, remember?) The light on the walls creates two narrow pillars. The tree, actually there is more than one, is centered by also partially hidden. And there is a light which is not a window, or at least not first a window, it seems electronic, on the right. The image is inorganic and organic. Dark and light. Cold and warm. It asks you to create a narrative.

Edward Hopper would feel right at home. Not only for the shapes and the loneliness and nostalgia, but for the use of color, too.

Hà Nội is an intriguing book, in the most rewarding sense of that word.

According to his website, Vanhees’s work has been exhibited at the Angkor Photo Festival, the Matca Space for Photography, and the Galerie Huit Arles, among other places, and his images have appeared in magazines such as The Washington Post, Fujilove, Vice Asia, Urbanautica and Posi+Tive, and L’Oeil de la Photographie, again among others.

Hà Nội is only 144 pages long. There are 64 color images and two brief essays (in both Vietnamese and English). Apparently, only 500 copies were printed, each one signed and numbered. In terms of book-arts, dimensions and paper-weight and design, it’s an elegant book to hold in your hand. The one I have is #421.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.