Think, for a moment, about the location of a shared experience for our imagination and desire.

It could be a concert hall, a ballet stage, an outdoor amphitheater. It could be gargantuan, intimate, or anywhere in between. It is a space for us to experience something outside ourselves, together.

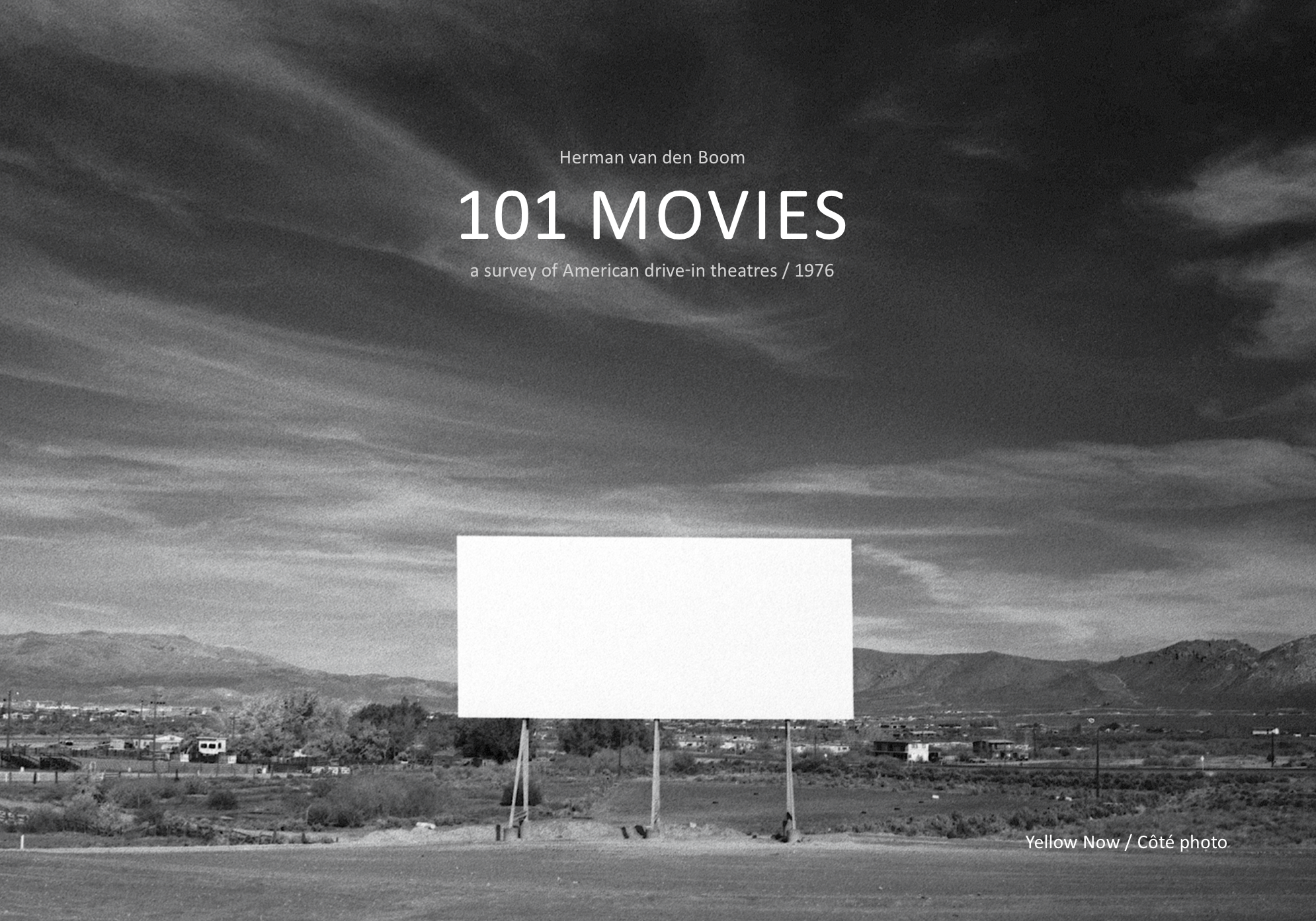

“100 Movies: A survey of American drive-in theatres / 1976″

Published by Editions Yellow Now, 2022

review by W. Scott Olsen

What this space can be, and what this space should be, has inspired architects and artists since the ancient world. The oldest outdoor amphitheater we have remembered was at Pompeii, thought to have been built between 80 and 70 BCE. In Elizabethan London, during the time of Shakespeare, there were at least eight playhouses running. Today, the Kabuki-Za theater in Tokyo seats 1,964, while the Kremlhoftheater Villach in Austria seats only eight. The Sydney Opera House defines a harbor and city. The Fargo Theatre, in North Dakota, is an art-deco icon.

We want a place to experience love and fear and adventure and tragedy, safely, with others.

Movie theaters, of course, are a special wonder. They are commonplace and nearly sacred. Some are physically extraordinary – the Traumplast Leonberg in Baden-Württemberg, for example, has a world-record screen measuring 127.2 feet by 68.8 feet. Some offer special seats, gourmet food, rooftop viewing, even beds instead of chairs. Most, however, are more modest. A dark room and a seat comfortable enough to make our bodies irrelevant.

The American Drive-In movie theater, however, is in a category of its own. Americans love cars and spectacles. We love real nighttime and being secret in public. We love the panorama of the sky and moon and good or bad weather. A bit like a private booth in a swanky restaurant or opera house, the drive-in movie theater allowed us to be in a private room among a hundred private rooms, all watching the same movie, together.

I remember drive-in movie theaters well. And now I have this book on my desk: “101 Movies: a survey of American drive-in theatres / 1976.” The book is wonderful, nostalgic, artful and poignant. It is not sentimental, though. It’s documentary work that evokes memories of the past, informed by the time between then and now.

In the book’s introduction by Klaus Honnef, we learn, “In 1976 the Belgian artist, photographer, and designer Herman van den Boom traveled the USA. He was accompanied by his friend, the late Dutch photographer, artist and designer Toon Michiels. The two men shared a lot of interests, and the purpose of their trip was to photograph typical Americana: billboards, neon signs, stock figures of advertising campaigns, drive-in theatres. Michiels’ theme was neon signs, van den Boom’s – movie theaters.”

The movie screen is perhaps the most engaging blank space on the planet. We recognize them everywhere from basements to grand theaters, and we look at them with nothing short of a visceral anticipation. Something is going to appear in that space which, with luck, will transport us to another psychological space. It could be a romance, a drama, a deeply philosophical exploration, a science fiction adventure. Perhaps because of its size in front of us, the movie will be overwhelming and engrossing. There is a reason why we invented the IMAX theater. There’s a reason why we wear goggles for artificial intelligence games. To be completely immersed in another reality is, if not always pleasant, certainly alluring and transformative.

The drive-in movie theater is a particularly complicated and wonderful venue. The drive-in screen is always a screen in context. There is always the space around above and below the screen. There are varying distances from the screen. And then there is the atmosphere of the car, and the atmosphere outside the car to the concession booth or something similar.

Watching a movie in a drive-in theater was a way to have both a communal and private experience. You had the privacy of your own car and you also hda the community of other cars around you. Sometimes people would engage in a kind of audience response with meaningful car horn honks. The drive-in movie theater was a place of entertainment and romance, sexual adventure and deep relaxation. Inside your car was a world both private and within a public buzz.

In 1976 drive-in movie theaters were commonplace in the United States. Herman van den Boom decided to photograph them not in the evenings with parking lots filled with people and cars, but during the daytime, when the parking lots were empty and the surrounding countryside was illuminated by sunlight. In 1976, though, many of the theaters were already in decay and wearing out. The heyday had come and gone.

As Honnef goes on to say, “The silence that has taken root in these images is oppressive. It literally screams to be resolved, to be redeemed, even.”

At one level this book is a remarkable bit of historical record keeping. It is an interesting experience to look at the screens and marquees from old theaters across the United States and imagine what it would have been like to be there. There is a patina to many of the images which creates a sense of nostalgia if not remorse.

But there is something else about this book which is compelling. In most of the images there is a white rectangular box in the middle of the picture. The movie screen. That white space seems cut out from the reality of the rest of the environment. It sits there as a kind of gateway to an alternate universe.

The drive-in theatre screen was nothing less than a frame around the idea of transformative hope. Anything could appear there.

You look at these screens not so much as physical plywood and paint as much as “Insert Imagination Here.” I’m not talking about the kind of imagination you would get at a frame shop, where you would look at a fancy frame and think what picture do I have that would go in here? The whiteness of the screen and its intentional uniform blankness is an invitation to insert everything from Godzilla to Humphrey Bogart to Clint Eastwood. The best of the images in this book seem to create an almost three-dimensional feeling, but the third dimension is one of fantasy.

“101 Movies” also contains images of old marquees. On the marquees, the names of some movies still remain. Beyond the Grave. Killer Force. The Outlaw Josey Wales. Godzilla versus Megalodon. Those titles give a great hint to the milieu of the time. Many of the images show the screens from behind the sturdy steel or rotting wood of the supports. A couple of the images show the drive-in theaters being used for alternate purposes such as flea markets. But the real power of this book comes from those images that show the screen from the viewers’ side. It does not matter what environment that screen is in because it is always the Other. It is always a portal. It is always some space where the hills or the forests or whatever surrounded stop and everything else is possible.

Looking at this book is a fine and odd experience. The images are all well done and visually compelling. But more often than not, I would turn a page, scan the image, and then get lost in a memory of my own. I would see a picture of two speaker boxes hanging on a pole and I would remember their weight and temperature as I would lift one off a pole and hang it inside the window of my car. Much like the blank screen transports me too any one of a million other stories, the pages of this book transport me to a million other memories. If this book is archaeology, then it is in archaeology around the settings of my own hope and desire. And we always learn something new about today when we look at the past.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.