There is little doubt that many of us have a fascination with outtakes, or the B roll, or the material left on a cutting room floor. Something about the other work can be a rewarding, sideways look into the aesthetic, work habits, and decisions of an artist.

“Zone Eleven” by Mike Mandel

Photographs by Ansel Adams. Text by Erin O’Toole.

Published by Damiani, 2021

review by W. Scott Olsen

Failed attempts are often as illuminating to our understanding of an artist as successes. But we cannot neglect the fact that they are failed attempts. The B role is not the A role. The stuff on the cutting room floor in many cases deserves to be on the cutting room floor. Much in the same way, bootleg music recordings are wonderful in terms of nostalgia and memory, but they are in general horrible recordings. It is a danger to confuse successful work with outtakes, especially when the artist is not the one making the choices.

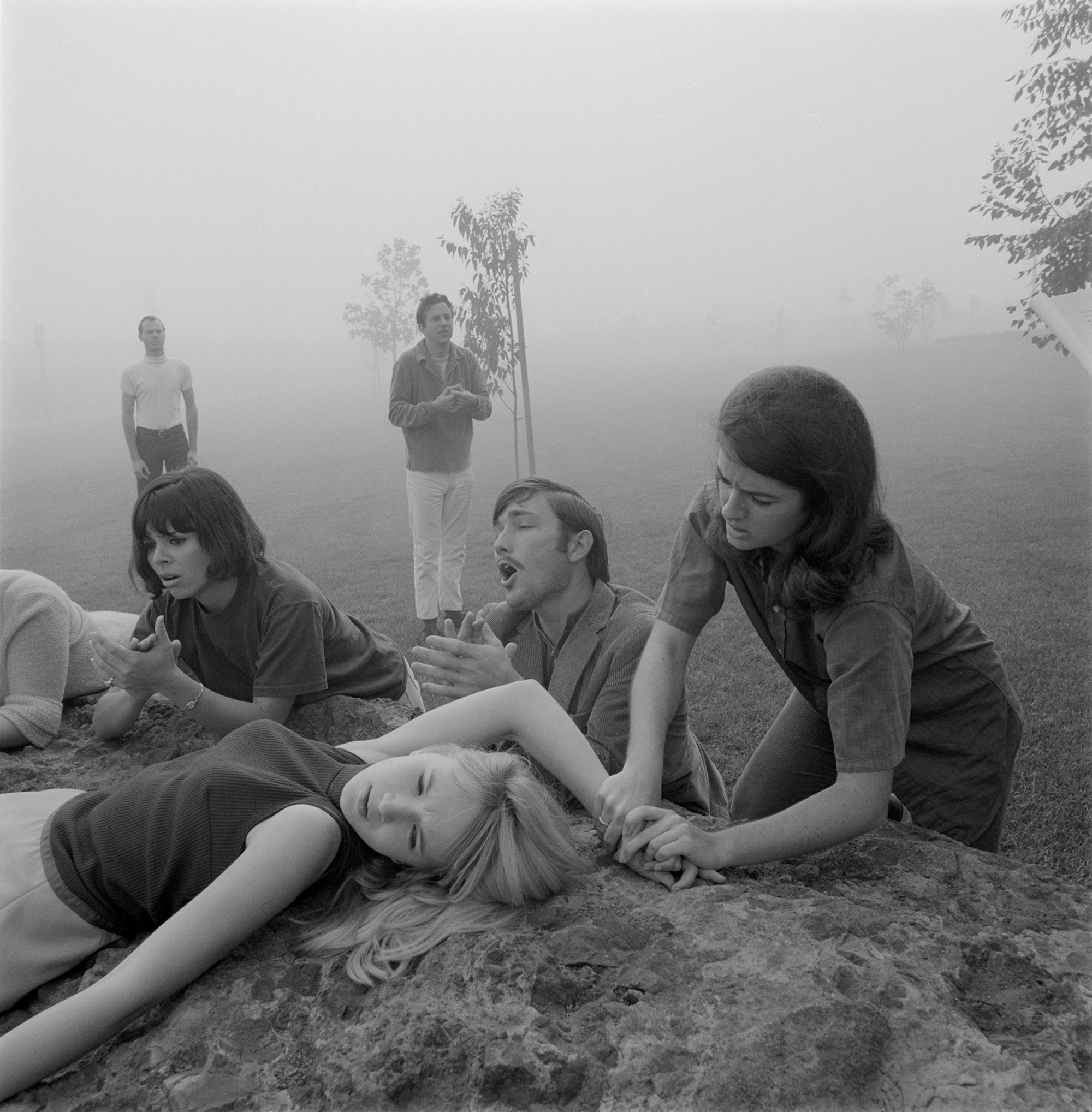

This dichotomy is at the heart of my problem with a new book of Ansel Adams photography called Zone Eleven, a collection of Ansel Adams photographs selected by Mike Mandel. Mandel, editor of the justly famous photobook Evidence, collected images from the Center for Creative Photography, the California Museum of Photography and elsewhere, to examine a side of Ansel Adams we seldom see.

What a wonderful idea!

I am a great fan of Mandel’s Evidence. There was, in that volume, a sense of developing insight. The images spoke deeply, and I left the book with new ways of thinking about crime, about photography, about fine art and documentary work, and more.

However, sadly, this is not the case with Zone Eleven.

In truth, I have several issues with this book. Its design is not very attractive. The text, which should be an introduction to contextualize the images that follow, is cast off as an afterword – ideas that come well after an impression of the photography has already set in.

Many of the images are mundane. Many of the images lack much insight at all. Several of them are gut-punch wonderful, but they are overshadowed by the rest.

Nonetheless, Erin O’Toole’s essay, “Mike and Ansel,” at the end of this book is really very good. In fact, it is the best thing about this volume. O’Toole is an associate curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and her essay is both a narrative of Mike Mandel and Ansel Adams meeting as well as an aesthetic explanation/defense of the project’s idea.

O’Toole writes, “This book is a collaboration of sorts between Mandel and Adams, except that the photographs Mandel selected for inclusion were not sanctioned by Adams for this purpose, and are likely ones he himself never would have chosen. Adams shot the pictures, but Mandel has adopted them and given them new meaning through sequencing. Given his long interest in popular forms of photography, it is not surprising that Mandel chose Adams’s commercial work as his subject. These are essentially vernacular pictures that happen to be made by Ansel Adams – totally unlike Adams’s best known photographs, which Mandel terms ‘unitary,’ meaning singular pictures that don’t depend on what comes before or after. The pictures in Zone Eleven are more open, less self-contained. Mandel has seen something special in each of them that others might overlook and transformed them through canny selection and juxtaposition.”

Let me repeat part of that quote. “…the photographs Mandel selected for inclusion were not sanctioned by Adams for this purpose, and are likely ones he himself never would have chosen.” That speaks volumes. I have no issue with a scholar digging in the detritus – oftentimes an artist is the last one to understand the power of their own work – but then the scholar needs to step up and do some explaining.

Elsewhere in the essay, O’Toole writes, “…Mandel decided the time was right to revisit the concept of interpreting Adams’s work…Mandel decided to explore a relatively unknown side of his production, namely the pictures he made for hire…Zone Eleven – the title of which references Adams’s famous Zone System for film exposure and development – is an homage tinged with Mandel’s absurdist brand of humor.”

This is a great idea. But in this book it does not work. The pictures are offered without context, without commentary, and as such seem very much like the castaways of a photographer we all know well. Mandel may have seen something in them, but he does not say what.

Of course there are some wonderful images in the book. But the very best of them do not compare to Adams’s better known work. If the organization and depth of the book rely on Mandel’s “absurdist sense of humor,” then I don’t get it. What this book needs is a bit of old-fashioned context. “Section Three: Fortune Magazine,” for example. With that little bit of explanation, and the accompanying understanding of the influence of editors, art-directors, etc., I would start to look for, and appreciate, the elements of genius that surface through the rest.

If you are a fan of Ansel Adams, or of Mike Mandel, or Erin O’Toole, you should buy this book. This is solid B roll material. If you’re not already a fan, there are other and better places to start.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.

Cary

January 14, 2022 at 21:52

Odd that W. Scott Olsen himself neglects to contextualize – namely whether the photos selected to illustrate his point that they are dismissable photos, “the castaways of a photographer we all know well,” from the book are his selection or the publisher’s press selection. In a newspaper the abbreviated account which neglecst to say what the problem with these is, or if these are among the “gut-punch wonderful”might be a question of available space. “The Big Five” hardly needs more context, and for followers of the medium context others are amply supplied even here by other contemporary work, contradicting the idea that the world is simply “over” Ansel Adams.

In fact it might, as with his color work, even though disparaged as lesser work by Adams himself, shows his eye more adventurous than with his iconic parks photos, more newly contemporary if not in these “with it” in contemporary color vs an older “street” style, and there may be much to learn from them, as Adams himself did, by simply looking. Give his other work not just an “A” but an “A+” to contextualize these.