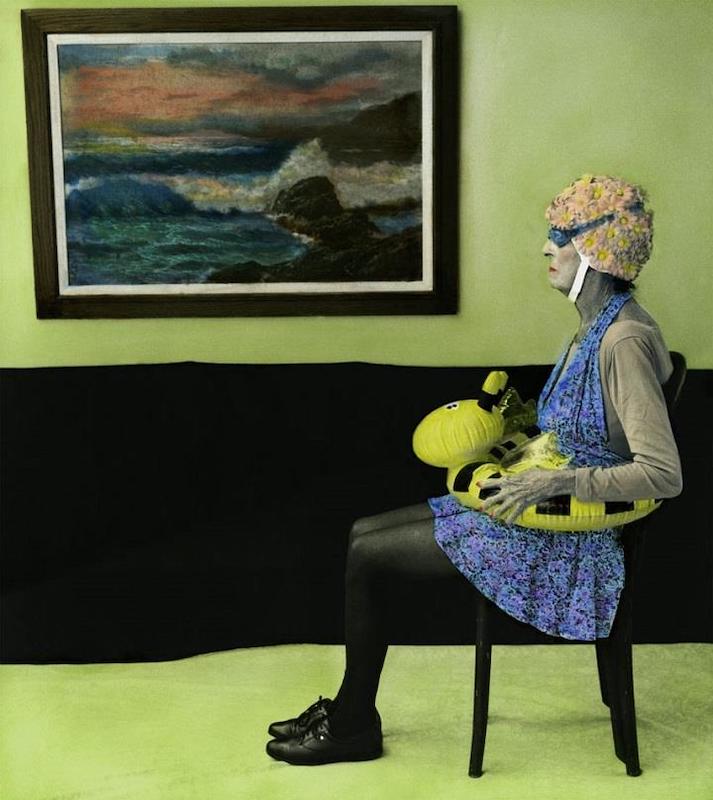

Aline Smithson is an interdisciplinary artist, educator, and editor based in Los Angeles, California. Her practice examines the archetypal foundations of the creative impulse and she uses humor and pathos to explore the performative potential of photography. She received a BA in art from the University of California at Santa Barbara and was accepted into the College of Creative Studies, studying under artists such as William Wegman, Allen Ruppersburg, and Charles Garabian. After a decade-long career as a New York Fashion Editor, Smithson returned to Los Angeles and to her own artistic practice.

She has exhibited widely including over 40 solo shows at institutions such as the Griffin Museum of Photography, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Fort Collins Museum of Contemporary Art, the San Jose Art Museum, the Shanghai, Lishui, and Pingyqo Festivals in China, The Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, the Center of Fine Art Photography in Colorado, the Tagomago Gallery in Barcelona and Paris, and the Obscura Gallery in Santa Fe. In addition, her work is held in a number of public collections and her photographs have been featured in publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, PDN, Communication Arts, Eyemazing, Real Simple, Los Angeles, Visura, Shots, Pozytyw, and Silvershotz magazines.

In 2007, Smithson founded LENSCRATCH, a photography journal that celebrates a different contemporary photographer each day. She has been the Gallery Editor for Light Leaks Magazine, a contributing writer for Diffusion, Don’t Take Pictures, Lucida, and F Stop Magazines, has written book reviews for photo-eye, and has provided the forewords for artist’s books by Tom Chambers, Meg Griffiths, Flash Forward 12, Robert Rutoed, Nancy Baron, among others. Smithson has curated and jurored exhibitions for a number of galleries, organizations, and on-line magazines, including Review Santa Fe, Critical Mass, Flash Forward, and the Griffin Museum. In addition, she is a reviewer and educator at many photo festivals across the United States. Smithson has been teaching at the Los Angeles Center of Photography since 2001and also teaches at a variety of institutions such as ICP, SFW, MMW, and others.

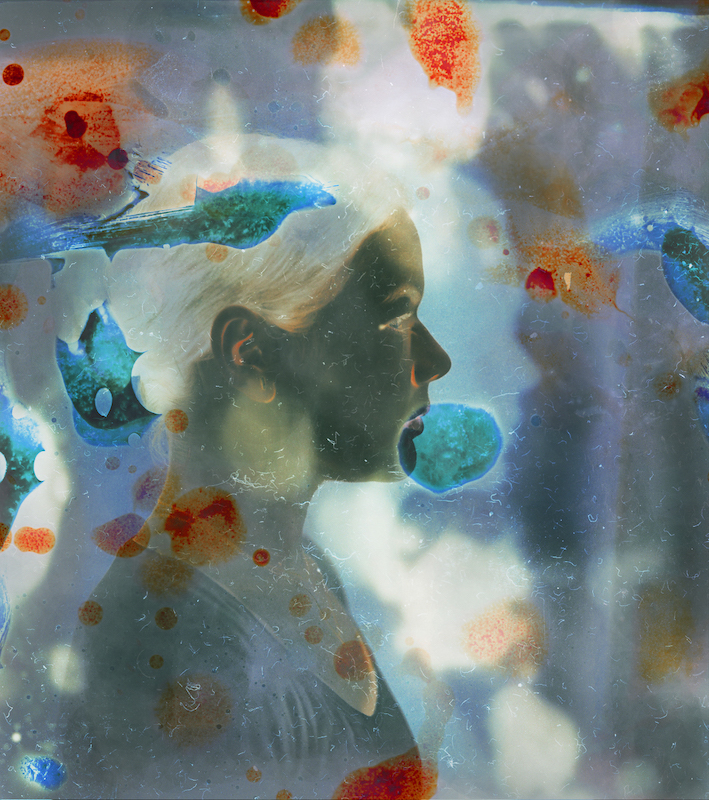

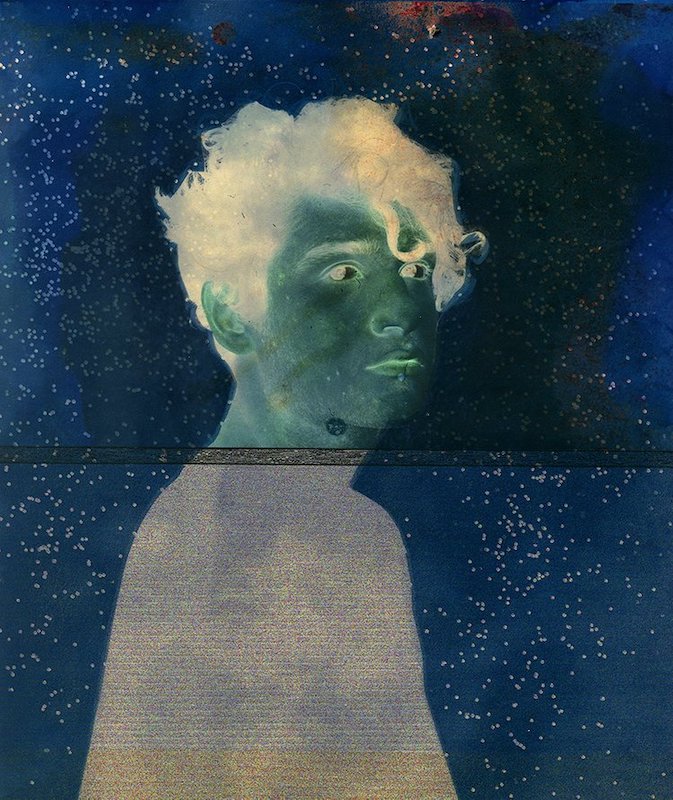

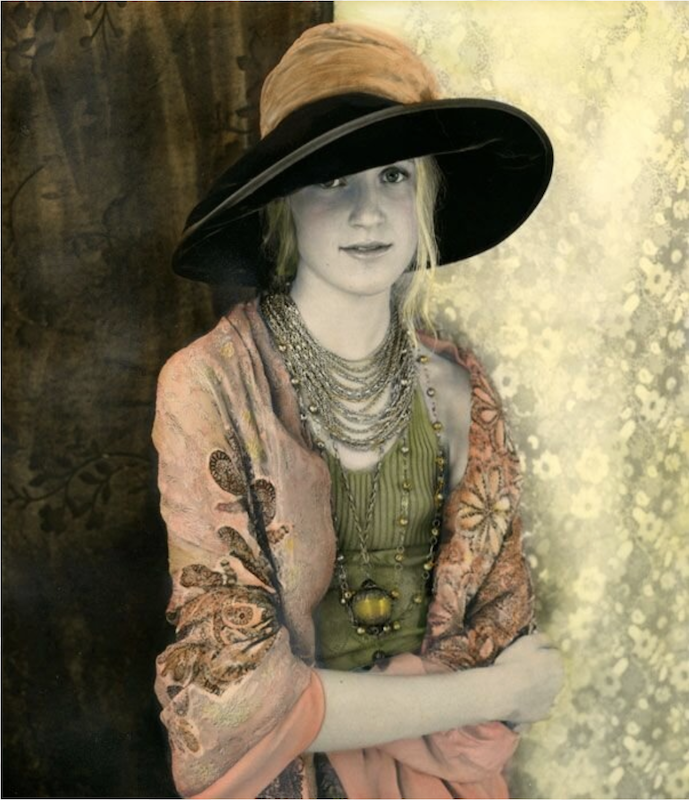

In 2012, Smithson received the Rising Star Award through the Griffin Museum of Photography for her contributions to the photographic community. In 2014 and 2019, Smithson’s work was selected for Critical Mass Top 50 and she received the Excellence in Teaching Award from CENTER. In 2015, the Magenta Foundation published her retrospective monograph, Self & Others: Portrait as Autobiography. In 2016, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum commissioned Smithson to create a series of portraits for the upcoming Faces of Our Planet Exhibition. In 2018 and 2019, Smithson was a finalist in the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize and exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in London. She was commissioned to create the book, LOST: Los Angeles for Kris Graves Projects which now sold out. Peanut Press released her monograph, Fugue State, in Fall 2021. Her books are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum, the Los Angeles Contemporary Art Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, London, the Metropolitan Museum, the Guggenheim, among others. Smithson was honored as a 2022 Hasselblad Heroine. With the exception of her cell phone, she only shoots film.

I’m thrilled to bring this interview to FRAMES readers. It’s been in the works for some months, and getting to speak about it finally is exciting.

Usually I begin with a narrative about the person I’ve interviewed, their work, perhaps how we met. And honestly, I wrote about four different versions of that for this article. In the end, I thought there was nothing which I could say that would be more important or interesting than the responses Aline Smithson provided to my questions, so I am skipping right to that.

Almost, anyway. The one thing I will say before you read is more of a “housekeeping” matter. Smithson’s bodies of work are so extensive that adding descriptions of each seemed to take away from the narrative, so I urge you to open a second browser window set to Smithson’s portfolio page so you can fill in information about the different projects. You can click here to do that.

NOW we can get started.

DNJ: I’ve read that you grew up in Los Angeles. Tell us about your family life as a child.

AS: I grew up in the wonderful neighborhood of Silver Lake in Los Angeles, a very diverse community with families from all over the globe. Our house was on a hill above the original Walt Disney Studios. Before I was born, my mother could look out from the kitchen sink window and see Disney animators drawing from real-life Bambis. Disney played a big part in my childhood as family friends were animators and colorists, and we had unlimited passes to Disneyland. I realize now that my love of taxidermy, mannequins, animatronic figures, and just about anything fake came from being immersed in that fantasy world.

My parents were loving and humorous, and my sister and I grew up laughing (and fighting). My father was a cowboy at one point, but by the time I was born, he was a salesperson and a hobbyist photographer with a darkroom in the basement. He was also a musician. My mother was a vocal teacher for the Burbank schools, and both played the guitar. The soundtrack of my childhood was songs of the West and a wide variety of folk songs. Neither of my parents was an artist, but my uncle was the Supervisor of Art for the LA City schools. I developed a great appreciation of art from him. Through him, I also learned about mid-century architecture and design. My neighborhood had many notable mid-century houses by Neutra, Schindler, and Lautner; my friends and I would take long walks assessing these spectacularly designed homes. Recently, the LA Times featured a mid-century home restoration, and I realized it was a childhood friend’s home. There we played with troll dolls, unaware of how beautifully designed the house was. It appears it wasn’t a coincidence that I married an architect.

DNJ: What were you like as a child?

AS: I was a happy kid with lots of time to disappear into my imagination. I never felt special or that I stood out. I was always creating something out of nothing, whether it was cooking, drawing, sewing, or making things. Both my parents worked, so I developed tools to entertain myself. Boredom is a great motivator. Today, no one ever gets bored; there is always a screen to entertain us.

DNJ: When did you take your first photograph? What did you photograph, if you remember?

AS: I loved photographs but was never very interested in cameras; I was more interested in pursuing art, mainly drawing and painting. My nose was always in a magazine or book. I started using a camera in college, never with a specific focus, as I was deeply involved in large colorist oil painting. I made a few soulful self-portraits, probably taken after a breakup with a boyfriend. My photography began in earnest once I had children, as I documented their lives and created the family album. I took a class at UCLA to better learn how to use my Pentax K1000. In that class, I discovered my uncle’s 2.8F Twin Lens Rolleiflex. That was the beginning of my photography journey, as I realized I could use a camera to make art. I still can pinpoint the image that signaled a photograph was “Art.”

DNJ: What challenges do you face as a photographer?

AS: Mine is a long and winding answer to a difficult question. Digital cameras and the iPhone have made photography accessible to all, with good and bad results. There are more photographers than ever; more people going after the same awards, contests, and opportunities. I find a ubiquitousness to a lot of photography being done today.

If I can be more general, I am disturbed by the state of photography today. The only people who can actively take part in applying to contests and attending portfolio reviews are those with financial means. For recent grads and educators, spending $35-50 on a submission, then tacking on framing and shipping at $250-300, is nearly impossible. And spending $2-3000 to attend a portfolio review is out of the question—this narrows who can participate. We need a new template. We all work for pennies (running Lenscratch, I work for no compensation). All this presents a challenging journey to make a living.

DNJ: Sometimes, one project leads naturally to another, and other times a series stands alone, with nothing more to add with further work. In your work, I see a long-term project of shooting portraits of women and a multiplicity other, varied series—your brilliant pandemic project on social distancing, being one example. Where do the ideas you work with come from? Does one series influence another, and if so, how?

AS: All of my work is a form of self-portraiture. I think about an idea for a long time before I make the images. I have a legacy of creating portraits, especially of children and women.

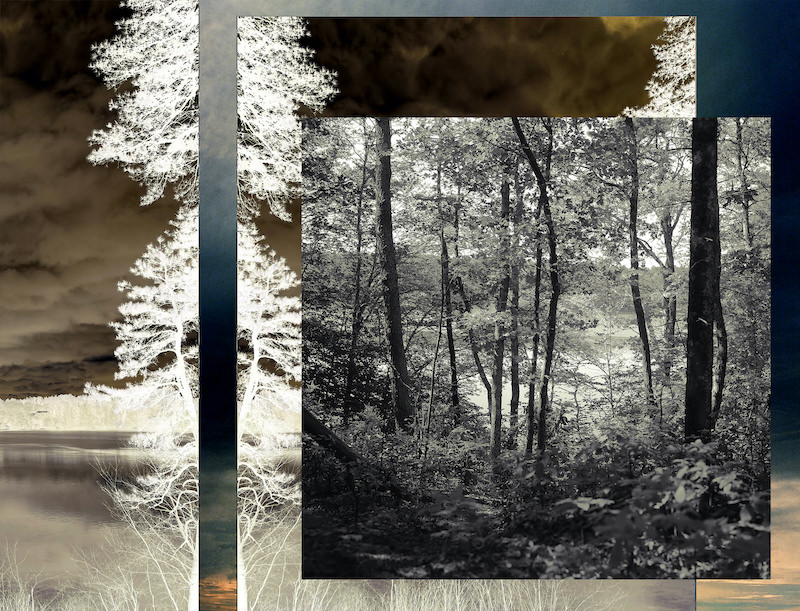

My “Paradise” series is the best example of one project leading to another. For the past 25 years, I have made pictures at a lake that my family visits each year. The photographs were in black and white for the first seven or eight years, and then I moved to color. I have now made work for the series for over 25 years. “Paradise” spawned a second way of looking at family histories and the legacies of physical objects, titled “In Case of Rain.” “In Case of Rain” reignited my love of paper dolls, which sparked another series, “Child’s Play,” where I reconsidered the play templates we give children to think about adulthood. That series led to another series titled “Photographs of Photographs.”

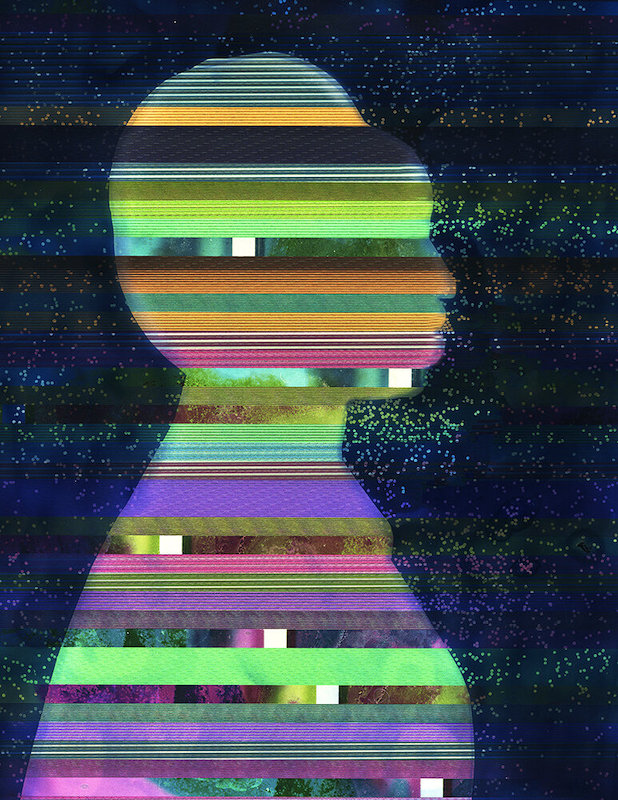

I also have several projects that consider the legacy of the physical photograph: People I Don’t Know, Fugue State, and Fugue State Revisited.

DNJ: Those of us over a certain age remember battling to be taken seriously as women in the workplace; that battle is still ongoing in the art world. Though slowly improving, museums still hold more works by men, and many high-profile galleries are the same. Do you consider yourself a feminist? If so, does it show up in your work? Do you have any thoughts on the status of women in the photo world?

AS: I am a feminist; it shows up more in how I lead my life, perhaps more than in my art. On the one hand, we have a long way to go to force institutions to recognize the importance of women’s voices and stories.

I have been keeping a mental tally of how women show up in the photo world, and, on many levels, it’s an exciting time for women. More women are garnering awards, exhibitions, and accolades. There are increasing numbers of women curators and photo center and festival directors, and they are interested in work showing women’s stories and concerns.

Twenty years ago, many male curators were not interested in work about motherhood or women’s issues. Today, I see a significant shift in the work that is getting attention. Beyond female empowerment, I see many institutions and organizations elevating and celebrating people of color. Honestly, it’s all looooooong overdue. And I’m sorry, but we don’t need to see another Robert Frank exhibition; he’s had his turn.

DNJ: We have all had images that somehow we can’t make work, though the germ of something we love is in there. What do you do when you encounter this?

AS: I keep tons of one-off or half-baked images for later exploration.

As a fashion editor, I had to edit all the film work; because of that, I became an exacting and critical editor of my work. Because I shoot film, much of my editing takes place before I click the shutter, though I leave myself open to chance and creative left turns. Sometimes, what I might have considered a failure turns into a worthy series. I learn more from my failures than from my successes.

DNJ: What do you do when you encounter a period of a creative block?

AS: I’m always thinking about the next project(s) – I usually have 3-4 projects in my head. My problem is finding the time to create the work. I look at probably a thousand or more portfolios annually and am often blown away by the work others have made. Still, it doesn’t affect my journey as I continue to revisit the influences from my lifetime, which are unique to me. Much of my inspiration comes from a heightened awareness of our world and how it impacts us in ways large and small. But I also love to visit art museums and look at paintings for inspiration.

DNJ: What do you hope the viewer takes from your work? Does it vary by series?

AS: It varies by series. The things I was interested in eight to ten years ago are not as interesting to me now. Our world has radically changed, inspiring me to work at a deeper level. Right now, I want to sound the alarm that our work may not make it into the future, as our hard drives won’t last forever.

DNJ: Most of the people I have interviewed haven’t experienced as many “sides of the table” as you have: you are a noted photographer with your own art practice, you have had several photobooks published, you teach, you do workshops, you run the Lenscratch site (and for many years wrote most entries), you’re a frequent portfolio reviewer, you mentor people, you serve as a juror and a curator. How do you make the time for all of this? Are there times you wish you “just said no,” and why, if so?

AS: Ha! After three years of saying “Yes” to everything—during the pandemic, I knew many organizations needed to entertain and maintain their memberships, and I wanted to support their efforts—I needed to say “NO” for my mental and artistic health. I was teaching all the time, moderating artist talks, giving artist talks, blah blah blah… By the summer, I was utterly burned out and sick of ME.

I also have several regular obligations—I sit on three boards, work closely with the Lenscratch Student Prize winners, have a monthly mentoring session with the winner, Drew Leventhal, and have quarterly check-ins with the group.

This past summer, I slowed down and said I was having a fall of “NO.” I’m teaching just one class and doing some mentoring, so I have a few free days here and there to make work, which is a blessing.

DNJ: What are the considerations that are most important to you when you are submitting work to a juried competition like Critical Mass or Lens Culture? By the same token, from your experiences jurying such competitions, what advice would you offer FRAMES readers when they contemplate entering one?

AS: Submitting work to major competitions means the project should be unique, timely, and well-articulated. The written statement can also genuinely elevate the photographs.

There are competitions to avoid that are just a money grab for an organization. It’s a good idea to ask other photographers about their experiences with particular galleries and organizations. I never enjoy telling a photographer not to apply to something, but when everyone who submits gets in or where everyone gets a prize, it diminishes your achievement. It’s a tough day on social media when photographers celebrate “wins” in competitions that are strictly financial wins for the organization. My rule of thumb: if it’s a competition that has many categories, it’s usually a money grab.

DNJ: I believe that sitting on all sides of that table gives you unique perspectives of the photo world. Does this impact your thoughts when jurying? What are your most important considerations when jurying an exhibition?

AS: It sounds simple, but submit work that aligns with the show’s theme. Submit well-crafted work—is the image in focus? Have you cleaned all the dust? Is it your best presentation?

Don’t send five versions of the same photograph. Stick to the theme, but then think beyond the obvious. Surprise and delight the juror. You should only submit the minimum, as adding more images doesn’t cause the juror to fall in love with the work. Consider how your work looks viewed at scale; is the image readable when it’s small? Many jurying platforms don’t allow the juror a big, delicious view of your files.

If you get into an exhibition, send your best prints and, if workable financially, get your pieces professionally framed. There are some venues where I’ve given awards to images before I see them in person, and with one person I awarded First Place, the work arrived with a beaten-up frame, the mat had a footprint on it, and everything was dirty. That experience not only shifted how I regard that artist, but it made the organization look bad.

DNJ: You have been quite supportive of work pushing boundaries in form from what has been traditionally called “photo.” What do you think are the coming trends in photography? How far can someone push boundaries and have their work still be photography?

AS: We live in a time where photography is ubiquitous—everything has already been photographed. I’ve seen hundreds of beautiful and classic landscape photographs, and it’s rare to be surprised. A pristine black-and-white landscape is still lovely, but it doesn’t make my heart skip a beat.

I came out of an art program that incorporated all genres of art—photo with painting, painting with sculpture, sculpture with etching, etc. Photography suffered when Fine Art MFA programs broke it out to a singular focus. It made photography more sterile. In decades past, when artistry was found in the darkroom, it was a creative process, but this idea that photography must be pure and straightforward is ridiculous and restrictive. I’m a rule breaker and admirer of others who challenge the norm. I also love when artists use their processes to align with the subject (like Matthew Brandt and Ella Morton).

Using art to draw attention to issues can be remarkably compelling. The most significant trends in photography are where photographers become storytellers, mining their lives to examine ideas of family and self, using new capture, ephemera, and old family photos. People are also making outstanding, creative works about climate change, the history of the land, and using archives to examine the past. I genuinely believe we are in the Golden Age of photography, where everything is possible.

DNJ: What do you think about the creation of images via AI? Can a photographic one ever be a ‘photograph’?

AS: Change is hard, even for me, and I am very open-minded. Whenever an artist challenges the norm, those who are not as adventurous criticize the new methodologies. It took me a long time to appreciate manipulated iPhone photography and find its validity. Part of me is still judgmental about the ease with which photographers can alter their images using pre-set templates on their phones. As a film shooter, I still hold a lot of anger about how digital transformed my practice.

There will always be new technologies, and photography is constantly in a state of change. AI is transforming photography… or perhaps it is simply transforming pixels, which might be completely different. Right now, I’m on the fence about it.

DNJ: What’s next on the horizon for you?

AS: After taking the fall off, in January, I’ll start teaching again for ICP, LACP, SFW, and the Griffin Museum, plus a ton of private mentoring. Two solo shows are coming up. I’m in a collective with a fantastic group of women, and we have a traveling exhibition that will crisscross the country over the next two years. I’m working on several small books, a new project, releasing NFTs, and of course, working on Lenscratch each day—oh yes, and reviewing at five different portfolio reviews. It’s a lot to juggle, and I try to stay calm.

Thank you Diana, for this opportunity to chat with you and I appreciate all you do for our community.

I know I am probably seeming like a gushing teen fan girl here, but I’ll say it once again anyway. I’m ever so thrilled to have gotten to bring this interview with Smithson to readers of FRAMES. I hope you enjoyed reading about Smithson and her work as much as I enjoyed having this incredible opportunity to ask questions of such a powerful and gracious presence in the photo community. Thank you for reading. And thank you, Aline, for everything – this interview, and everything you do for photographers and the photo community.

ALINE SMITHSON

Marky Kauffmann

January 8, 2023 at 16:12

Thank you for this interview. I admire Aline Smithson a great deal. Learning about her childhood was fascinating. And reading about her ideas and photo philosophies was truly enlightening.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

February 7, 2023 at 01:11

Thank you so much, Marky, for reading and for your comment. ❤️