“This land pulses with life. It breathes in me; it breathes around me; it breathes in spite of me. When I walk on this land, I am walking on the heartbeat of the past and the future.”

– Brenda Sutton Rose

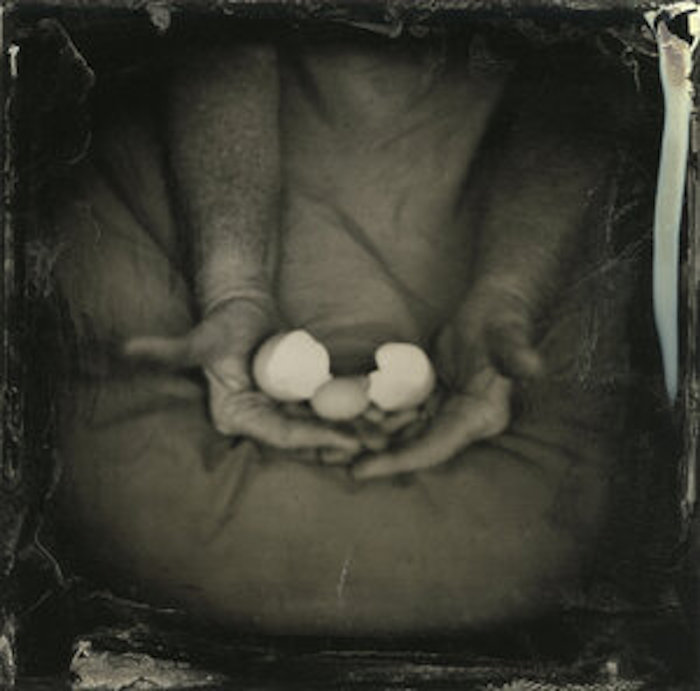

Barbara Dombach was born and raised on her family’s farm in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where she still lives today. A self-taught photographic artist, she has spent over 35 years using the camera to interpret herself and her world. Dombach holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology from Millersville University. She works with various photographic processes, including black and white film, Wet Plate Collodion, Lumen, and Cyanotype. Her camera choice includes digital, large and medium format, toy, twin lens, and 35 mm film. Dombach has taught, juried exhibits, lectured, and exhibited works in eleven solo exhibitions and numerous group exhibits. Recognition for her work includes being a Critical Mass Finalist, Julia Margaret Cameron Awards, and Spider Black & White Awards. She was an Artist in Residence at Acadia National Park and was awarded an Artist Grant by Lancaster City. Her images have appeared in Jill Enfield’s Guide to Photographic Alternative Processes, Square, Seities, Photo Techniques, The Hand, Imprints, and Diffusion.

I no longer recall how I first found Barbara Dombach’s work, but it immediately impacted me. Some people prefer images that precisely offer exactly what the photographer saw, no more, no less. But I find those less attractive than the ones that invoke my curiosity. Dombach’s world, as presented through her imagery, definitely did that! Many images were unusual, quirky, curious, and highly enigmatic. I’d go so far as to call some “odd” or “puzzling.” (Odd and puzzling are fine with me because that encourages me to keep with the image to determine the meaning.)

I had yet to learn – until now – what Dombach’s pictures meant and hence fabricated meanings based on my interpretation of what lay within the frame. I liked that they let my imagination run free and did not pedantically tell me what they showed me.

The fact that she generally works with more traditional media, in combination with her sometimes quixotic imagery, is why I invited her to talk to FRAMES readers about her work and her practice.

DNJ: Tell us about your childhood.

BD: I grew up in a farming family and have been close to the farming community my entire life. In addition to farming, my parents drove school buses; my mother was one of the first women drivers in Pennsylvania.

My mother was a talented artist who drew and painted. She influenced me greatly in leaning into photography.

I was a tomboy and wore my older brother’s hand-me-downs, played in the mud, pulled weeds, and helped with farming. Curious and filled with wonder, I was always asking questions. Growing up on a farm fueled my curiosity and was, to my mind, the perfect adventure a girl could have. My interests were nature, horses, tractors, planting and harvesting crops, and gardening. I was a member of the 4-H club and raised beef for several years.

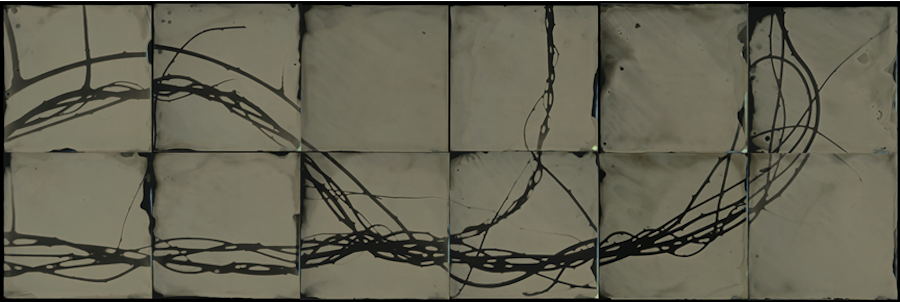

Due to my overtly talkative nature, my grandfather would offer me a dime to be silent for ten minutes, something at which I never succeeded (which was also the genesis for my series Not a Dime.

I still live on the farm and still like getting my hands dirty.

DNJ: When did you get the “photography bug?”

BD: I was probably around nine when my mother let me use her small Argus Argoflex seventy-five roll film camera. It was similar to a TLR with one lens to compose and another for photo capture. I was charmed by the large bright waist-level viewfinder with a flip-up cover that protected the ground glass. Looking downward into that viewfinder changed my world. Most likely, my first photograph was of my mother. I loved looking at my mother’s pictures and longed for my own camera. (I still have my mother’s camera displayed on my shelf.)

When I was thirteen, I began a lawn mowing business to fund purchasing a camera. With some help from my father, because of that job, I was able to purchase an Argus 35mm and also paid to buy and process Kodachrome film.

I entered photography when it was not considered an art form, at least in my area of the country. Photography served as a reference from which to draw or paint. So, from the beginning, I have had to prove my knowledge and talent. That made me even more determined to change the attitude of the art community here. It took time to become accepted. Reflecting upon my fine art photography journey, I was lucky to have encouragement from male and female artists who shared their trials and errors with me.

My desire to create using the camera has thrived for over 40 years. My camera of choice has evolved with technological changes, but the thrill of looking through the viewfinder has remained strong.

DNJ: Tell us about the various series from which I have featured images.

BD: Not a Single Dime – The series tells of my childhood experience. I was so curious and talkative that my grandfather would offer me a dime to be silent for ten minutes.

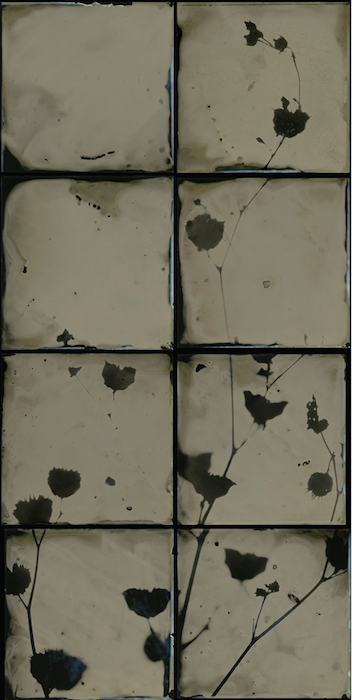

Spiritus – As a child, I had a congenital disability that required braces to straighten my legs. Now much older, I have rediscovered nature’s mysteries under my feet; I also found that each specimen I chose is imperfect, as I once was.

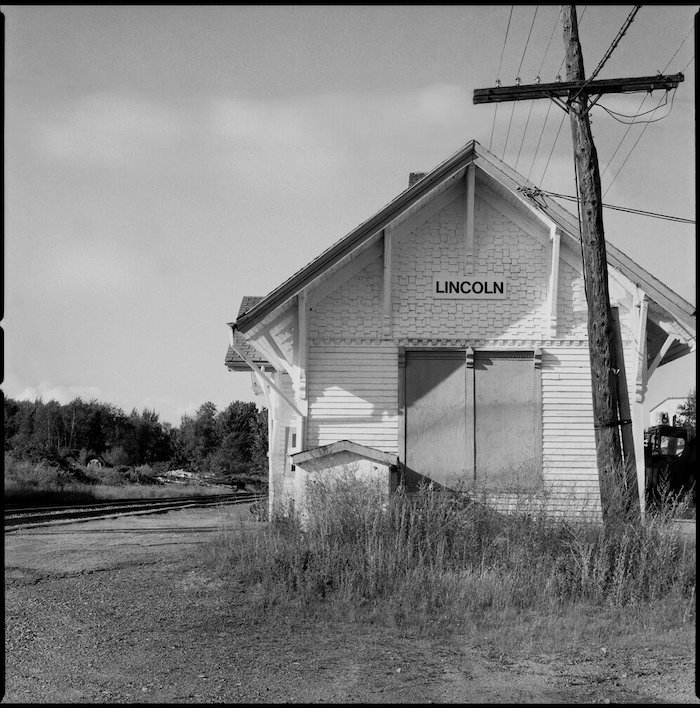

Maine Light – Maine Light is a fourteen-year project journeying to northern Maine, documenting the area situated amid the area’s paper manufacturers.

series

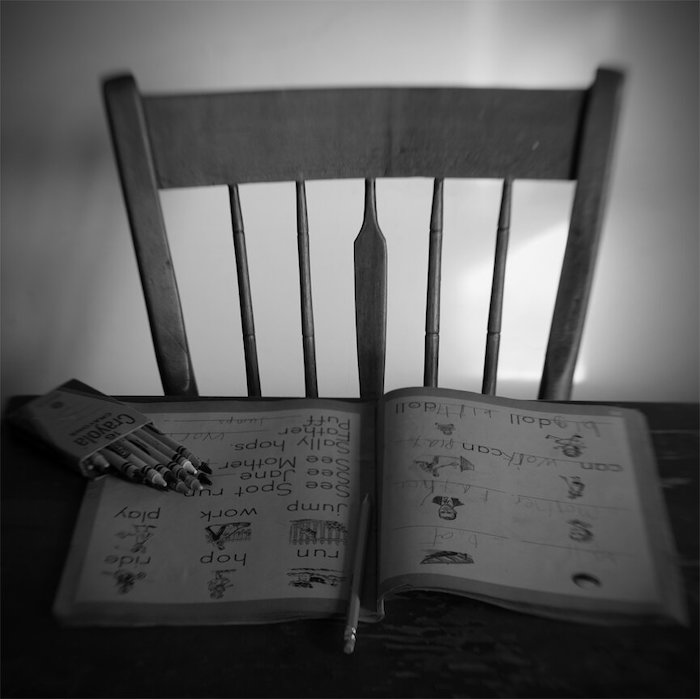

The House that No One Lives In – Using negatives made in the house I grew up in, along with ones from additional homes, this series reflects on our life cycle within the places we call home.

Forbidden – Based on my grandmother’s diaries, this project examines the conflicts and problems she faced due to extreme religious restrictions.

DNJ: Where do the ideas you work with come from? How do they influence each other if they do?

BD: My images come from my life experiences—the things that make me “me.” My projects are diverse because I visually express what my mind considers or imagines. Inspiration materializes, for example, reading my grandmother’s diaries, seeing a child’s drawing, searching for a sense of place, or remembering an unfinished dream. The elements of mystery and ambiguity contained within each frame is how I tell stories.

The image Waiting for the Student depicts a desk with an open workbook and an empty chair because that was a part of my life. I have always had a short attention span; as a student, I found it challenging to concentrate on my studies.

Forbidden inspired me to create both the Ties that Bind and the Unfinished Dreams series.

On the other hand, the Maine Light project served to propel me to a new, additional direction and voice in my photographic work.

DNJ: What prompted you to turn the camera on yourself, and why have you continued making self-portraits?

BD: Eleven years ago, I decided to tell my life stories.

During my mother’s illness, she and I would talk about her childhood, and stories of my childhood crept into our conversations. Reflecting on our discussions after she had passed, I found she had planted seeds of inspiration for me to pursue. Amidst my feelings of loss, I missed my time together with her, talking. She had always encouraged me; I felt broken and longed for her stories to endure. But in the immediate period, there were other more pressing causes; settling her estate was demanding and problematic. (I even created an image about that, The Burden.) I also transcribed my grandmother’s diaries during that confusing time; they became the basis for the Forbidden series.

With that behind me, I had time to concentrate more fully on my photography. I was making plates for Forbidden, but my thoughts repeatedly returned to my mother’s stories. Soon to be a senior citizen, I wondered why I had given so little attention to my own stories.

It was challenging, though. After all, these are my stories – of loss, defeat, heartbreak, and joy – the essence of my life. Fear of being exposed for who I am and where I came from made my hands tremble, but it was time to put fear aside and begin anyway.

DNJ: You mainly work with traditional photographic materials, including wet plate. Tell us more about this and the evolution of learning the different ones you use.

BD: I am a self-taught artist with an incurable passion for using a camera to interpret my world and life experiences. I have always had a darkroom where I work with silver gelatin photographs and process film. I also love history. While in college, I studied photographic history; that was how I discovered the early processes. Each method offers significant characteristics that impart an emotional value beyond what the negative alone offers. I learned historic presses from old manuals and books, with additional help from some photographers working in historical methods.

I began with cyanotypes because the process was easy to learn. However, Prussian blue only suited the message of some of my work. I used Lumen printing in the What’s on Your Plate series.

After transcribing my grandmother’s diaries for the Forbidden series, I knew I wanted to use a process that would underscore the challenges she endured due to rigid religious protocols. That led me to begin work with wet plate collodion, which involved a lot of trial and error. Filling the trash can was part of the learning process! Eventually, I got the process down and began making good plates.

DNJ: What do you hope the viewer takes from your work? Does it vary by series?

BD: My goal is to lead the viewer and let them ponder the meaning, not to feed it to them. I view myself as a guide, not a conqueror.

I gave up fearing viewers’ opinions when I stopped doing commercial photography. It allowed me to focus more on what I wanted to create and gave me more personal satisfaction and feelings of achievement.

I am elated if a viewer finds my work thought-provoking or feels a connection to it. Some stories resonate more than others; knowing what is behind the images sometimes changes their view. But I genuinely create the work for myself. It’s how I translate my life and the world around me, which is enough.

DNJ: We have all had images that somehow we can’t make work though the germ of something we love is in there. What do you do when you encounter this?

BD: When I see that an image has a seed of something special but doesn’t yet spark, I study it hoping to find the resolution. I might leave an “errant” picture dormant for a long time and then later re-examine it. In revisiting the image, I sometimes find something different from what I first saw. My muse guides some of this process (but I don’t always listen.)

DNJ: What do you do when you encounter a period of a creative block?

BD: At times, a creative block can last for a while. Unfortunately, this usually happens when I am overwhelmed by pain from long-ago back surgeries or a family crisis.

Living on a farm offers opportunities for me to reevaluate my direction. Inspiration will return – I must remain calm, meditate and allow the thoughts to enter. I am curious and enjoy wandering on paths or along old roadways. It is beneficial and sharpens my observation, ideas, and discoveries. Walking is good for my soul and helps to clear my thoughts.

DNJ: The battle for women photographers and artists to have equal recognition is still ongoing in art. It’s improving, but very slowly. Museums still hold more works by men, and the more well-known galleries still exhibit work by men more frequently than women. Do you have any thoughts on this? Do you consider yourself a feminist?

BD: I agree that museums exhibit men’s work more frequently. Over the years, though, I have seen more women photographers accepted into galleries. In time more acceptance will occur.

As I consider this question more deeply, I have to say that I do not consider myself a feminist but rather a woman who believes in the equality of talented individuals.

Photography is an evolving art form. Who can say for sure what the future will hold?

DNJ: What’s next on the horizon for you?

BD: I am working on more images for Not a Single Dime and bringing Forbidden to book form. I’ve started on the book design; it will likely change as the process unfolds. I’m in the process of looking for a publisher.

I am also working on a new project I envision as ultimately becoming a photobook.

Soon I will be revisiting my family albums for another new project. I have plans to create handmade books from some of my smaller projects.

I want to thank Barbara for taking the time to share her story with FRAMES readers.

BARBARA DOMBACH