Jennifer McClure is a fine art photographer based in New York City. After an early start, Jennifer returned to photography in 2001, taking classes at the School of Visual Arts and the International Center of Photography. In between, she acquired a B.A. in English Theory and Literature and began a long career in restaurants. She was a 2019 and 2017 Critical Mass Top 50 finalist and twice received the Arthur Griffin Legacy Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography’s annual juried exhibitions. Jennifer was awarded CENTER’s Editor’s Choice by Susan White of Vanity Fair in 2013 and has exhibited in numerous venues nationwide. She has taught workshops for Leica, PDN’s PhotoPlus Expo, the Maine Media Workshops, The Griffin Museum, and Fotofusion. Publications such as Vogue, GUP, The New Republic, Lenscratch, Feature Shoot, L’Oeil de la Photographie, The Photo Review, Dwell, and PDN have featured her work. Additionally, in 2015, McClure founded the Women’s Photo Alliance.

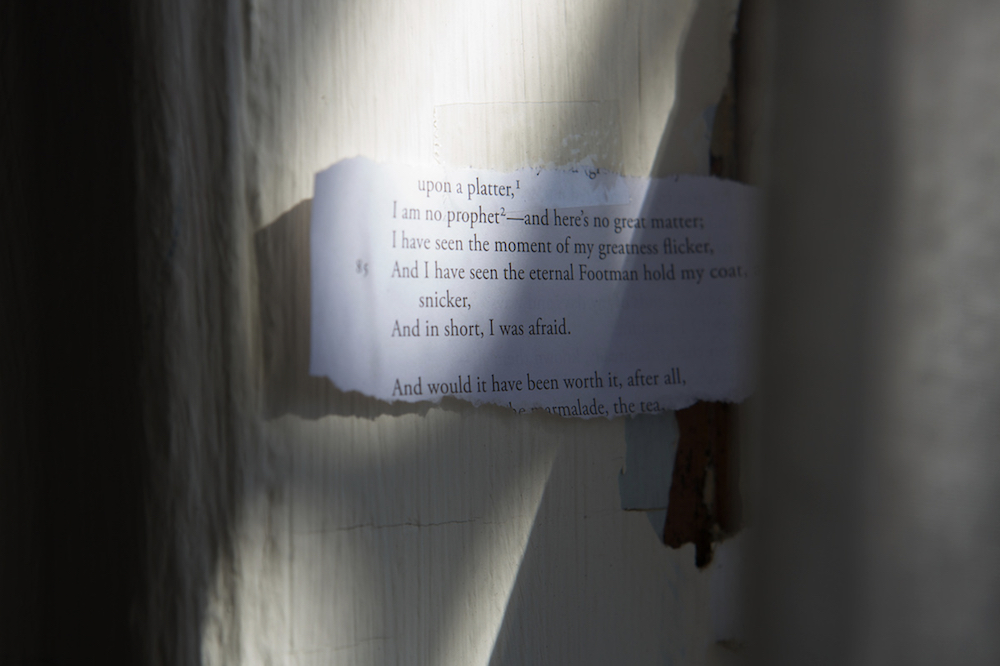

McClure makes the kind of work I most relate to—because it’s deeply personal. Often based on her life experiences, she uses a camera as a form of introspection to explore issues that could otherwise result in nights of lost sleep. As a former literature major, stories and poems often leak into her work, as evidenced by her titles in Still the Body, taken from a long form piece about pregnancy and fear called Plot, by Claudia Rankine. (Note: McClure obtained permission from Rankin to use the short excerpts.)

In researching this article, I read an interview and watched a video interview with McClure on the B and H website. One notable thing worth mentioning: McClure said that she made images for about five years before she felt the voice in her photographs was authentically hers. I feel like a similar story could be told by most serious artists—no matter how well-trained you are, there is always a period of trying on things, trying out things, before settling into something that comes across to ourselves as genuinely and consistently evoking what we want to say via our work.

Although it’s not a project McClure has on her website and I don’t have an image from it, in that interview, she showed a project I have always loved. It’s called Tired, the first project she made where she turned the camera on herself and her life. It’s distraught and yet quirkily elegant. The project is about a long bout with an autoimmune illness that left her tired and unable to function as she did previously.

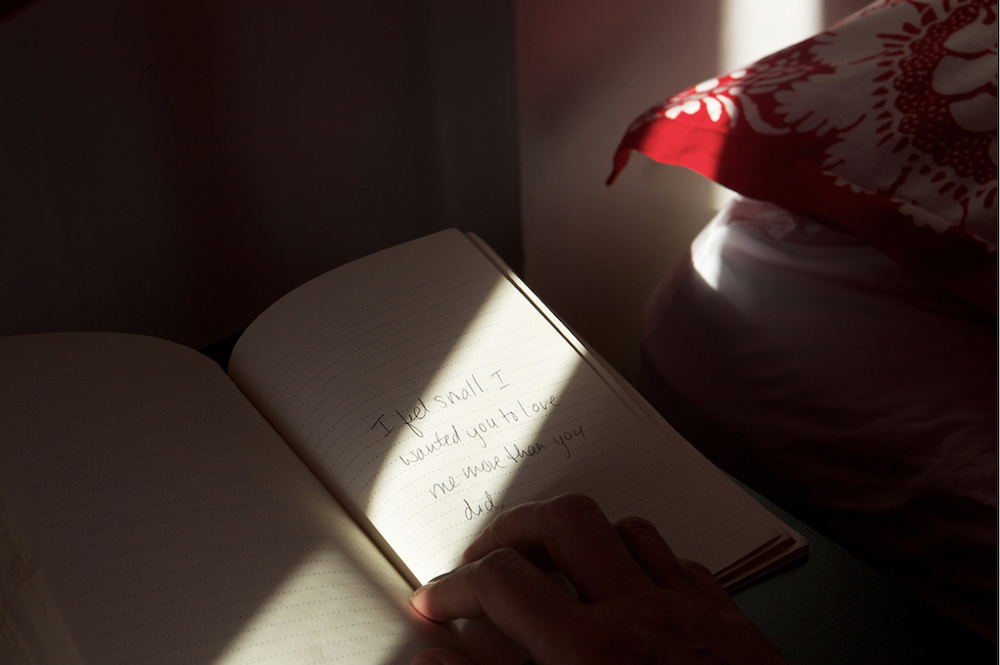

Reading her project statements and looking at her images, her longings and yearnings jump off the page at the viewer. Yet a humorous vein also sits within the frame, mixed with her weightier contemplation of relationships, motherhood, and other facets of her life as an American woman. She is also incredibly adept at using light to highlight what she wants us to focus upon in any given image. When making work in a small city apartment, this is no small feat. I know this well from working in my own small apartment, and then, sometimes from resort hotel rooms and condos where I have an entirely different amount and type of light than I do at home. I am in awe of McClure’s ability to do this so well given her living situation.

It’s worth stating that McClure uses writing and mind-mapping exercises to unlock and unleash ideas before she works, something she learned from studying with Cig Harvey. And for those interested in pursuing gallery shows and photo competitions, it’s instructive to read her thoughts about artist statements and project editing as spoken from the standpoint of an educator, portfolio reviewer and juror.

I asked McClure to provide short summaries of the projects reflected by the photographs I’ve selected for this article; they directly follow this paragraph. We are also fortunate to have the opportunity to look at several images from early-stage project on the effects of the intergenerational legacy of motherhood.

You Who Never Arrived: As I turned forty, I examined my failed relationships’ patterns and breakdowns. I staged my memories in hotel rooms, which were as impersonal and unlived-in as my romances tended to be. The stories I told myself about my loves were far more dramatic than my shared experiences, and the disconnect between fantasy and reality became increasingly apparent with each staged narrative.

Laws of Silence: This project is about letting go of the life I was programmed to live: the idea of the ‘American Dream’—I hadn’t experienced any of the joy that supposedly came with it. These pictures come from an emotional space of longing, of wishing for things that never were and might never be.

Still the Body: I got unexpectedly pregnant at 46. I made photos as a way to manage my anxiety, to bring order to the chaos. The act of photographing allowed me to observe the process as though it were happening to someone else. I began to appreciate the oddity, imbalance, and enormity of the experience.

Today, When I Could Do Nothing: My daughter was eighteen months old when the quarantine began. We started making pictures daily as a way to fill the hours. These were the only times I was entirely in the moment, not worried or anxious. I looked for magic and escape. I photographed the things I wanted to hold in my heart and tried to experience this strange new world through her eyes.

I relate so much to McClure’s portfolios because she works from the same place I do—personal life experiences. She is fearless and holds back nothing. We experience her feelings as they lay bleeding on the floor and then also share other, more peaceful times with her.

And now, here we go…

DNJ: What was your family life like? What did your parents do? Do you have siblings? Was anyone else in your family an artist or photographer?

JM: My father was a military judge, and my mother was a teacher. We moved around a lot, which was hard for a shy kid like me. My brother was a year and a half older and my constant companion. We weren’t artistic but voracious readers and loved escaping into books. My father bought a camera before being stationed in Japan, and like most families, we used it primarily to document travel and each other.

DNJ: What were you like as a child?

JM: I was an odd child. I loved observing other people. I could stare for hours at crowds moving by or groups around me. That same fascination likely fueled my love of reading. I wanted to know what others think about, what gets them through the day, and how they relate to each other.

DNJ: When did you take your first photograph? What was it of, if you remember?

JM: My first photograph was of my brother. I was seven or eight years old. My father had a few frames left in his Pentax K1000 and gave it to us to finish. We took it outside to the rice paddies by our house in Japan. I remember feeling giddy and delighted when we got the slides back. I couldn’t look at them enough. My parents got me a Kodak Disk camera shortly after.

DNJ: What prompted you to turn the camera on yourself, and what has kept you doing that?

JM: I first started doing self-portraits regularly after a long illness that left me tired all the time. I worked in a busy restaurant and could barely leave the house on my days off. My project ideas all stalled. Eventually, I began making self-portraits as a way to feel productive and connected to something outside of my apartment. If I could make some photos, even a handful, I didn’t feel like my day was wasted. Looking at those photographs gave me the distance I needed to process what was happening with my body and to separate my self-worth from that. I hadn’t planned on continuing. But other issues arose as I recuperated and thought about re-entering the world, the dating world specifically. Photography was the obvious way for me to work through my confusion again.

DNJ: Sometimes, one project leads naturally to another; other times, a series is done; nothing is left to say. Where do the ideas you work with come from? How do they influence each other if they do?

JM: My project ideas come from questions that keep me up at night, and there’s always something! They’re fueled by what I’m experiencing. I process my emotions best by getting them out of my head and into a photograph. The first self-portrait series on being tired led to one on dating, which led to one on being single, which led to one on my very unexpected marriage and pregnancy. One project naturally flows into the next. I know I’m stuck in my life if I lack an idea.

DNJ: We have all had images that somehow we can’t make work though the germ of something we love is in there. What do you do when you encounter this?

JM: I keep them to work on later, but I also recognize that they might be rough drafts. Sometimes I rework or alter them to spark a new idea or approach. I have some images that I return to repeatedly that I keep trying to insert into various projects. I know they won’t fit, but I make the effort. It’s my way of spending more time with the pieces so that I can let them go. And sometimes, they wander over to Instagram. I can show them love without forcing a concept that isn’t there.

DNJ: What do you do when you encounter a period of a creative block?

JM: I suffer and agonize. I think about selling my camera equipment because I’m obviously an imposter. I look into going back to school to study something else entirely. And then I get to work. I start making pictures of anything that’s happening around me. I go back to the basics, to the sheer delight of making a photograph to see what something looks like photographed. I stop focusing on developing project ideas and end goals and make a lot of pictures that no one else would ever see. And eventually, an idea reveals itself, or the question I have about my life becomes evident.

DNJ: What do you hope the viewer takes from your work? Does it vary by series?

JM: I don’t think much about what the viewer might take from my work. I make the photographs because I feel compelled to do so. I bring myself to my work as my most honest, authentic, and vulnerable. I’m always wonderfully surprised when people relate to my work, especially in ways I hadn’t expected.

DNJ: The battle for women photographers and artists to have equal recognition with men is still ongoing in the art world. It’s improving, but very slowly. Museums still hold more works by men, and the more well-known galleries still represent more men than women. Do you have any thoughts on this?

JM: I could write volumes. The art world needs more representation on many fronts, despite efforts made by many in the years after #metoo and George Floyd. Indeed, a greater variety of work is being shown, but the hard numbers on museum acquisitions and gallery sales continue to skew to white males. And I wonder if changing the art world is like a slow-moving ship or if recent efforts are merely performative.

Many projects that come from a female-identifying perspective are still dismissed or undervalued. The art world gives a themed show here and there but falls far short of accepting such work as part of the canon. That is true for most groups considered ‘other.’ We all have to be unrelenting as we knock on doors to get in and try to make change from within. I don’t have concrete answers or a game plan; it’s not an easy or simple fix.

DNJ: Do you consider yourself a feminist? If so, does it show up in your work, and in what form, if it does? How does Women’s Photo Alliance NYC figure into that?

JM: I am definitely a feminist. I continue to make stories specific to my experience, many of which are informed by my gender. Many male reviewers have suggested that this work is merely art therapy. My goal is to normalize art like mine, which is emotional and personal. I won’t change my work to make it more desirable to a broader audience.

I try to lift up and promote female-identifying photographers whenever I can, especially minorities within that category. When the opportunity presents itself, I send their names and work to people who hire and curate.

The purpose of the WPA is to extend that reach as far as possible, as well as validate and appreciate these photographers on an individual level.

DNJ: You are a noted photographer with your own art practice, you teach, you do workshops, you’re a frequent portfolio reviewer, you mentor people, and you have a young family. How do you make the time for all of this? Are there times you wish you “just said no,” and why, if so?

JM: I do not have time for all of this! I make time but at the expense of rest and self-care. Hopefully, this will change when my daughter starts kindergarten in the fall. I’m grateful for every opportunity to show and teach, so I don’t have any regrets there. I should have said no to myself several times, especially when completing long submissions with work I knew wasn’t ready. I know now that opting out of that cycle for a cycle or two is okay.

DNJ: I believe that sitting on all sides of ‘that table’ gives you unique perspectives of the photo world. Does this impact your thoughts when jurying or curating? What are the most critical considerations you consider when jurying an exhibition?

JM: The photographs for an exhibition all have to work together. That means some of my favorite images might have to come out of the final selection. That always hurts. But this is the same guiding principle when editing portfolios. I have had to cut some of my ‘beautiful darling’ anchor pieces from a series when they interrupt the flow of the entire body of work. Students absolutely hate that part of editing and sequencing (and always try to sneak them back in.) But the poetry of the final piece is the most important consideration on any ‘side of the table.’

DNJ: What advice do you have for our readers to consider when submitting work to a juried competition, such as Critical Mass, or working on a book proposal?

JM: My best advice is to get help with their selections and sequencing. Artists develop an emotional connection to certain pieces because they are attached to what they felt when making them or infused them with a meaning impossible for others to see. Getting other eyes on the work helps narrow it down to the most successful images. I advise them to hold on to some mystery in their selections, not to be literal or chronological. The project statement is critical and must be well-considered; it can’t be an afterthought. The words add context for the viewer and also help the photographer understand their own visual language.

DNJ: What’s next on the horizon for you?

JM: I’m working with the idea of maternal legacy (editorial note: some of the images we get a preview of view here!) I’m looking at how mothers in my family have raised their children over the decades and how I’m trying to mother differently. There’s a lot to process emotionally and photographically, and it is a challenging subject.

Professionally, I’m planning for an upcoming workshop with Maine Media in August. I’m teaching at ICP and the Griffin Museum. I have an exhibition at the Leica Gallery in Boston scheduled in the fall.

Readers, I hope you have enjoyed learning about McClure and her work as much as I have.

Thank you, Jennifer, for making the time to provide FRAMES readers with this fascinating glimpse into your working processes.

JENNIFER MCCLURE