I’m doing something different from my typical interview feature today. I experienced a few tough months from a workload and family standpoint, so I decided to do something that both inspired me and spread my love of the work of female/female-identifying photographers to a few more people than I can typically cover. We return to the single-person interview format next month.

I read an article recently called “Why Female Photographers Still Mimic the Male Gaze.” I found myself disagreeing with most of the author’s views, which amounted to the fact that women had yet to change how photo looks and is looked at. In my view, photography has been experiencing a remarkable shift, with increasing numbers of women making their mark in the field.

Not long ago, though, I spoke with an excellent female photographer friend about how and what we each photograph. Despite her obvious talent and acclaim, her work doesn’t speak to me as frequently as some other women’s. She commented (something to the effect of), “I think I shoot like a guy.” I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant since—tadaa!—she was not a man. But the comment stayed in the back of my mind. I’ve pondered this almost every time I see a photograph of hers—what about this work separates it from most images made by women? I’ve come to think that how she appraised her practice may be accurate.

The Male Gaze, coined by Laura Mulvey, and the oppositional Female Gaze have been extensively analyzed from the standpoint of sexual objectification and female agency. But don’t worry; I won’t bury you in film theory here. Instead, I ask, “Is there something more, something else, something different, that separates how and what women photograph?”

For me, it often means a particular manner of looking that differs between the sexes. To me, men are looking objectively, more observationally, more from a (mental or physical) distance, a direct way of seeing and presenting subject matter. Of course, since I am not a man, I cannot say this is the internal dialogue that happens. But do all men work this way? Likely not. But it is how their work often appears to me as the viewer.

Yet, isn’t that the same thing a female photographer does—observe cooly and directly? For me, with some exceptions, the answer is, “Oh heck, no!” Charlotte Jansen, the author of “Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze“, writes, “I was often surprised by the reasons for which women photograph women. They can be a way to understand identity, femininity, sexuality, beauty and bodies. The photographs women take of women can be a tool for challenging perceptions in the media, human rights, history, politics, aesthetics, technology, economy and ecology; to get at the unseen structures in our world and contribute to a broader understanding of society.” I propose that the true essence of the female gaze lies in women creating art crafted without the consideration of the male ego or male desire but instead with the focus on the wishes of the female maker and female viewer. While the work is often profoundly personal, many women also bring a sense of our universal experiences through their lenses. What sets the work of female photographers apart is their ability to encapsulate within their images the essence of their everyday experiences and emotions in a poignant, relatable, and sometimes haunting manner, breaking away from the purely observational gaze. At the same time, they break down traditional barriers and showcase the beauty of diverse seeing.

The imagery I have included here represents a small survey of what we women photographers are doing via our work. I’ve purposely selected imagery that addresses a myriad of themes, materials, and conceptual approaches.

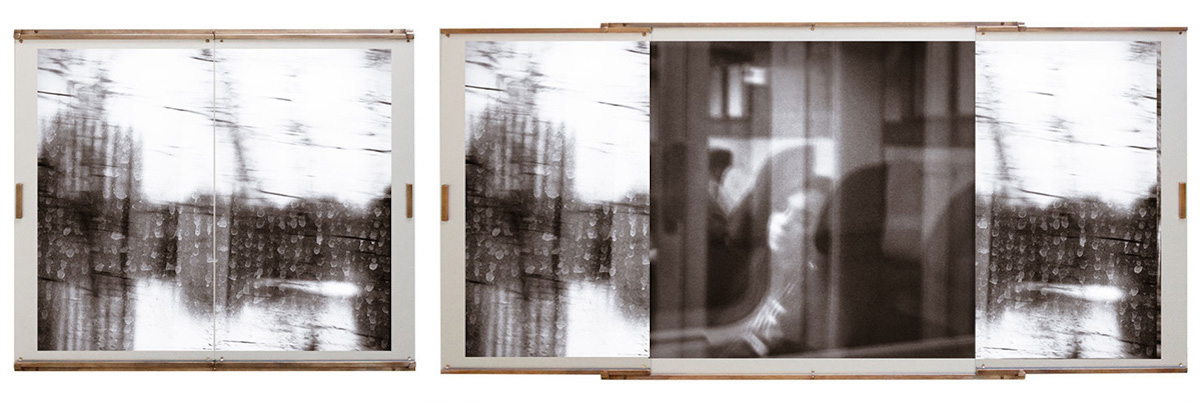

left: detail, closed image; right: detail, open image

This first image is from the series Voyage (En Train) by Amandine Nabarra. She created the series during trips via train from Genoa to Milan and Turin. It depicts the remembered fragments seen from windows while at the same time presenting us with the rapid motion of landscape whizzing by. Nabarra offers the work as ten single images divided down the center. She mounted these on sliding rails, mimicking train doors opening and closing. That is the kicker for me. The series is an ingenious use of blur, ICM, and materials to underscore her experience of remembered landscape fragmentation and train ride, making the viewer feel what she recalls. (Aluminum and brass railing fabrication by Luigi Alessandrini.)

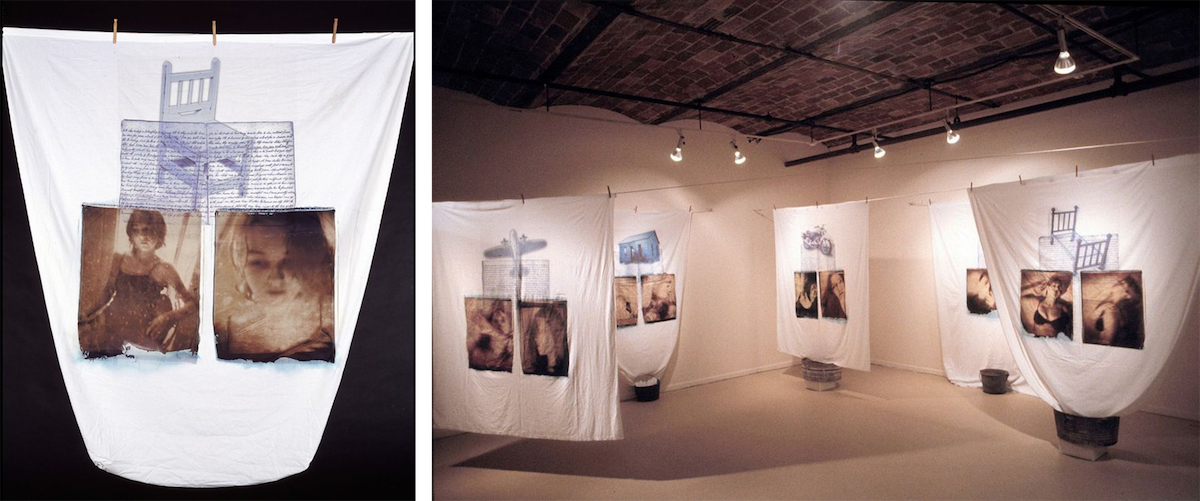

left: detail; right: installation view, Gallery Henoch, NYC

Secrets of the Magdalena Laundries by Diane Fenster has long been a photo installation I wish I had made. The work reveals the imagined inner lives of 19th and 20th-century Irish indigent or immoral women imprisoned and enslaved via the Church. Fenster’s incisive use of materials gives potency to the work: found bedsheets serve as the delivery media, directly referencing the sheets belonging to others that the subjugated women laundered. Her large format Polaroid photos portray both ‘kitten-esque’ poses and postures that attempt to evade the viewer and might read as emulating the male gaze if seen as singly framed prints. But as transfers to the sheets, they represent more: the human stains they work to erase, the figurative stains to their reputations, their societally imposed shame. You can view a video walk-through of the installation here. (Original installation soundscape created by Michael McNabb).

Donna Cosentino’s photograph of Caroline is a visual veneration of love for a great-grandchild, a ‘girl crush’. The image doesn’t focus on the face or the child’s actions. Instead, Cosentino shows us the dichotomy of contemporary girlhood—somewhat dishevelled curls and split ends buttressing the poofy, lacy, make-believe princess attire of many little girls’ dreams. In doing so, Cosentino has encapsulated the societal norms and mores the child will need to embrace or reject as she advances to adulthood while imbuing tenderness that shows genuine affection for the child.

left: partial installation view, The Pond Room; right: partial installation view, The Pool

In a departure from the rest of the imagery here, for this work by Grace Weston, I include her artist’s synopsis I found online.

It reads, “In 2018, I created a photo-based installation at Nine Gallery in Portland, ‘Escaping Gravity: Breathing, Dying, Swimming, Flying.’ It addressed my older brother’s death by drowning in a pond when he was eight years old and my learning to swim quite late in life, an activity that now fills me with joy and a sense of freedom. Using enlarged photos of miniature swimmers printed on large chiffon banners, audio of water splashing, and theatre lights that gave the illusion of the surface of water rippling on the ceiling, I built the installation with two separate chambers suggesting the underwater experience of both a pond and a swimming pool. I had never done a multimedia installation; it stretched me artistically, technically, and emotionally beyond what I had ever done.”

The work is a vast departure from the more humorous social commentary usually found in Weston’s work. If one avoided The Pond section of the installation, one might think it is a joyous series about the artist’s enchantment with swimming. And it is. But once one crosses from The Pool to The Pond, we learn it is concurrently a harrowing dive into the family dynamics and painful loss borne of this tragic event. Even without experiencing the installation in person, I am enveloped by emotions of both sorrow and joy, loss and freedom. A video walk-through of the installation is here.

For her series Somewhere Else, Jane Szabo constructed models of homes from maps, took them on her travels to ‘somewhere else’, then photographed them within interior and exterior locations to show us her wanderlust and visceral longing for somewhere else—past or future—a place that may or may not exist in reality. The maps are of sites she explored as a child or longs to escape to in the future. Upon viewing the imagery, I wondered how Szabo knew of my longing or whether this internal struggle between where we are and where we think we want to be exists in all of us. I recall sitting in despair some nights, thinking, “I just want to go home,” but knowing there is no such place anymore; it is strictly something constructed within my thoughts and dreams. Szabo’s conceptual work allows us to ponder our longing for such wanderings.

left: detail; right: partial installation view

Using photography, found objects and encaustic medium, Jessica Burko’s installation Fractured and Found explores her personal experience trying to meet societal expectations of her myriad roles: wife, mother, artist, daughter, curator, and friend. Drawers holding photographic self-portraits speak to the compartmentalized boxes women must simultaneously occupy to fulfil roles that often have competing responsibilities. The photographs reinforce a sense of being pulled in too many directions. Transferring them to layers of encaustic enhances the distressed feeling. The emulsion is a kind of skin showing how fractured we can become trying to be superwoman. We can recognize our lives in this emotional and compelling work.

In her series Beneath the Ice, Lara Gilks revisits her childhood fears of falling through the edge of a frozen lake near the reeds and winter flowers. In her youth, she imagined herself falling through and reaching for the plants to save me. She’s always felt a conflict between exhilaration and fear, and it carried into her adult life. We’ve all seen, and perhaps made, images of frozen flowers. While the conceit of color seduces us to the imagery, her addition of people, selective positioning, and obfuscation of elements within the frame change the dynamic. It destabilizes us as to what is happening in the story. That makes the work effective at evoking the internal struggle of both fear and peace.

Norma Córdova’s Mood, Memory, or Myth explores subjects not allowed for discussion within her birth family—fear, anxiety, and pleasure—and being raised within a family unwilling or unable to discuss them. It left her voiceless, but she reclaims her agency, desires, and expression by depicting these taboos in her photographs. Córdova works with analog processes as she feels it allows her to interject more of herself into her projects. I find this image, The Hands, The Kiss, enigmatic. It leaves me with more questions than answers about what is happening: a teenage self practicing taboo kissing? A grown woman making peace with the Mexican expectation for marriage and family? Does the seemingly low tide have a meaning, or is it a chance occurrence? The woman is graceful. I find her clues invite me to stay with it.

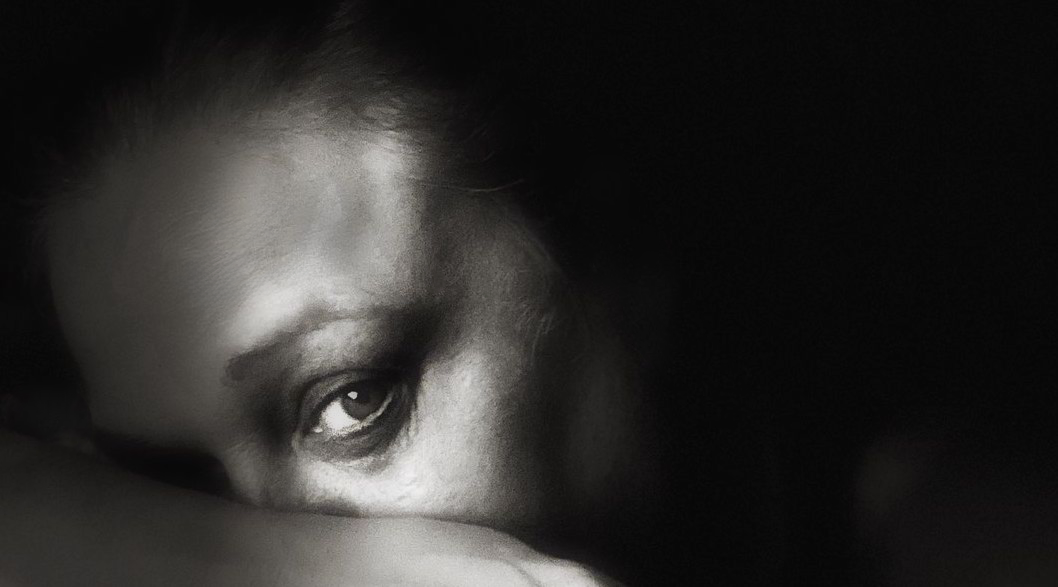

After three years of avoiding what must not be spoken of, Shari Yantra Marcacci bravely opened the bedroom and hospital doors to expose the heartache, frustration, and grief of infertility. The Journey is a most intimate and personal project, and she allows us to feel what she and many others have experienced. This image speaks directly to that Samsara-like existence as each month brings another cycle of beginning again in the quest to conceive a child. The gesture of her self-portrait expresses dashed hopes, sorrow, and the sense of time falling through the hourglass. It makes me want to reach out and give the woman in the image a hug. Via this project, Marcacci brings the conversation out from behind closed doors and into the open.

Susan Rosenberg Jones was widowed after 32 years of marriage when her husband succumbed to a long illness. She then lived with a rollercoaster of mixed emotions ranging from grief to regrets to loneliness. Once she decided to test the waters of dating again, she serendipitously found love with the second man she met, who became her second husband. And why not? Who amongst us would not want to be looked at through eyes that scream pure and unconditional love into our faces and camera lenses? Second Time Around is her series documenting their life together. This image from it simultaneously brings me joy to see how Rosenberg’s husband looks at her with such adoration and jealousy that I don’t have someone who looks at me that way. A portrait can be a historical record or a defining moment in someone’s life. This majestically captured slice-of-life image is both.

After the birth of her two sons, Suzanne Révy left the publishing world and raised her children full-time. As a degreed photographer and photo editor, she began documenting her children’s lives and her emotional response to those years, creating several portfolio series. The final was I Could Not Prove the Years Had Feet, from which this image, Summer Evening, emerged. It’s an intriguing and mysterious photograph that is as much about light and form as it is about the person. As much unknown as known exists within the frame, a perfect encapsulation of the future unfolding in the boy’s life. Yet, the form and lighting, how she used them to frame the boy, infuse it with love and mystery. And for me, that speaks equally about that in-between time in life as it does her photographic conventions. What mother has not lamented how swiftly these precious years fly away?

I hope you enjoy these works as much as I do; they are a testament to these artists’ passion, dedication, unique vision and storytelling skills. It is long past time that the historically male-dominated field recognizes and celebrates the much-needed change that female photographers are bringing to the table.

Thank you to all the artists for allowing me to present your work to my readers.

ARTIST BIOS:

Amandine Nabarra is a French-born American artist. She has exhibited in numerous shows in the USA, Europe and Australia. Her work is in over 40 private and public collections like Le Centre Pompidou in France, The Getty Research Center in Los Angeles, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. Her books are part of curricula in some of the most prestigious art and design universities. She lives and works in Los Angeles.

Diane Fenster: I view myself as an alchemist, using alternative processes, toy cameras, and digital tools to delve into fundamental human conditions and issues. My work is literary and emotional, full of symbolism and multiple layers of meaning. I have exhibited since 1990 and first received notice during the era of early experimentations with digital imaging. My work has appeared in numerous publications. My work has been internationally exhibited and is part of museum, corporate and private collections.

Donna Cosentino has been passionately engaged in Photography since that first moment of darkroom magic experienced in 1971. She began teaching photography at Palomar College thirty years ago. During that time, she also ran the International Photography Competition at the San Diego County Fair, managed the Photographer’s Gallery in Escondido, and ran California destination photography workshops with her business, Photographic Explorations. Now a retired Palomar College photography faculty member, she has initiated The Photographer’s Eye Collective in Escondido.

Grace Weston: Based in Portland, Oregon, Grace has gained international recognition for her unique style of staged narrative photography. Her award-winning artwork has been shown in numerous exhibitions and publications and is held in many public and private collections. Grace has also been commissioned to create work in the editorial world for magazines, book covers, CDs and posters.

Jane Szabo: Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Jane Szabo merges a love for fabrication and materials with visceral photographic images. Szabo’s background creating props, miniatures and in set construction for the film and amusement industry infuses her creative process. Widely exhibited in both solo and group shows, her work is included in the permanent collection of the Lancaster Museum of Art & History, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Arte al Limite in Santiago, Chile, Centro de Arte Faro Cabo Mayor in Santander, Spain.

Jessica Burko resides in Boston, MA and has exhibited in solo and group shows across the U.S. since 1985. In addition to being a practicing artist, Burko is the Creative Director at the Photographic Resource Center, Cambridge, MA, as well as an independent curator with more than thirty exhibitions produced since 2000.

Lara Gilks: I am a photographer based in Wellington, New Zealand. I strive to test boundaries in my photography – creating images that are edgy and vacillate between being disconcerting and delicately calm. Through my photography, I explore the precipice between perfection and imperfection, human and inhuman, dream and reality.

Norma Córdova (aka shesaidred) is a Mexican-American artist born and raised in Oregon by hard-working Mexican immigrant parents. Her work has been exhibited in the US and abroad and published in The New Yorker, New York Times, Vice, PDN, and Lenscratch.

Shari Yantra Marcacci: Born in Switzerland, Shari Yantra Marcacci is a visual artist. Her work has been exhibited in group and juried exhibitions at institutions such as The Center of Fine Art Photography, the Los Angeles Center of Photography, the Houston Center for Photography, Think Tank Gallery, Los Angeles, Netanya Artists Association, Israel and Switzerland. Her work has been featured in F-STOP magazine, Shots Magazine, Lenscratch and Float Magazine.

Susan Rosenberg Jones is a portrait and documentary photographer based in New York City. Her work has been exhibited in solo and juried group exhibitions at the Center for Fine Art Photography, Baxter Street at CCNY, Howland Cultural Center, the Griffin Museum, the Center for Photographic Art, apexart Gallery, Foley Gallery, Plaxall Gallery, and Candela Books + Gallery, among others. Recent publications include Lenscratch, Strange Fire Collective, Fraction, Float Magazine, The American Scholar, F-Stop, and Down East magazine.

Suzanne Rèvy is a photographer, writer and educator. She earned a BFA in photography from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. After college, she worked as a photography editor in magazine publishing for fifteen years. In 2016, she earned her MFA in photography from the New Hampshire Institute of Art. She has exhibited at the Griffin Museum of Photography and the Danforth Museum of Art, among many other regional and national galleries. Révy is an adjunct professor of photography at Clark University in Worcester, MA. She is the associate editor of the online photography review magazine “What Will You Remember?” and serves on the board of the Photographic Resource Center in Cambridge, MA.

Christian Peacock

May 24, 2023 at 18:49

Wonderful commentary of excellent photography. Intelligent observation with a disciplined response. Two weeks ago I attended a gallery opening of a group show featuring photographers who identify themselves as female photographers photographing women with a women’s theme. Unfortunately most of the finished work was immature and naive in skills and talent of art. It was too self conscious of political theme and identity. Maybe because it was a stepping stone to a more nuance imagery to be created in the future. I appreciate your insight here and image selection. It’s a welcomed contribution to the Frames World..

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 25, 2023 at 05:55

I’m always a bit skittish to read comments made by men about my writing about women. But time after time, the Frames readers are so supportive of my writing and the work made by the artists I feature. (I should just get over it already, I guess.) You are no different. Your comment is so supportive. Thank you ever so much for this feedback. I appreciate it greatly.

Ellen Friedlander

May 24, 2023 at 21:21

Fabulous writing Diana! ♥️wonderful to include such a robust group of women artists! 🙌😘

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 25, 2023 at 05:50

Thank you so much, Ellen. So glad you enjoyed it.

W. Scott Olsen

May 25, 2023 at 16:41

Wonderful and engaging analysis. Very interesting reading and fine points.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 25, 2023 at 20:33

Thank you so much for reading and your kind thoughts. Appreciated.

Frank Styburski

May 25, 2023 at 19:26

I don’t think that there is a more ardent and effective advocate for the work of women artists than Diana Nicholette Jeon.

Thank you for an insightful article that considers the diversity of expression that is guided by feminine experiences. The art we expect is often better received than art that is outside of our experience. The fact that the sort we expect is guided by an establishment has a gender bias can’t be denied. Neither can it be denied that this bias prevents women from having their work seen and marketed. The vicious cycle reinforces itself.

Is the solution a more equitable position for women in the marketplace, corporate power structures, government, galleries and academia?

Is it enough for men to simply accept that gender influenced differences in art exist and have validity, without actually understanding them and embracing their value?

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 26, 2023 at 21:01

Thank you so much for your effusive confidence in my advocacy for women artists. Greatly appreciated. As to the solution? We are definitely working our way into the power structures, but the change is extremely slow going. Unfortunately.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 25, 2023 at 20:36

Thank you so much for your effusive confidence in my advocacy for women artists. Greatly appreciated. As to the solution? We are definitely working our way into the power structures, but the change is extremely slow going. Unfortunately.

Amandine

May 25, 2023 at 23:04

Thank you Diana for including my work in this interesting and though-provoking article.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 27, 2023 at 18:39

Thank you so much for your kind words, and for allowing me to write about your fascinating project.

pasang123

January 22, 2025 at 15:00

This article is a masterclass in storytelling. The narrative flow, combined with solid facts, made for an unbeatable reading experience

Diana Nicholette Jeon

February 24, 2025 at 16:12

Wow, what an incredibly wonderful comment to read. Thank you so very much for saying this. You made my year!