Author’s Note: I’m doing something different from my typical interview feature today. Recently, I was invited to be a portfolio reviewer for the Los Angeles Center of Photography (LACP) Exposure Reviews, which took place in early September. I “saved” this month’s space to highlight the work of the females whose work I reviewed. (I only saw one male photographer, but I am not leaving him out of my notice; I will note his work elsewhere since this feature looks at women’s work.) Next month, we return to the one-photographer interview format.)

Returning in format and ideas to my May 2023 feature, I again ask, “Is there something more, something else, something different, that separates how and what women photograph?” For me, the true essence of the female gaze lies in women creating art crafted without the consideration of the male ego or male desire but instead with the focus on the wishes of the female maker and female viewer. The themes and ideas discussed by most of the women I met with during the review echoed that idea. Most of the work was rooted in the deeply personal – life stories or perhaps a cause or ideal the artist had a great passion for.

The imagery I have included here represents a small survey of what we women photographers are doing via our work. It is representative of what I saw in my review sessions. Some work was more compelling than others, some projects much further along than others, but in the end, there was always at least one image or idea the women I saw worked with that made me decide to include their work in this feature. I have ordered them in the same order as I met with them, giving you a similar unfolding of experience as mine.

Robin Bell spent two years in Los Angeles feeling dislocated and isolated from her East Coast home. She noted a distinct cultural difference between the two coasts and created this series based on the idea of illusion, which was her take on how life in Los Angeles felt. Days gave way to months and years, yet the backyard pool remained constant. But it was always different, presenting her with myriad opportunities to photograph it as the illusions of changing light, colors, reflections, and shadows shifted. Hence, One Pool, Los Angeles, was born. She told me, “LA-specific details locate me – the palms, the range of aquas, the sharp light. But the images are also a mirage; it’s an uncertain, multidimensional, beautiful, and transient subterranean world.” I thought this image was serene and beautiful, and it most definitely sang of Los Angeles’s colors for me. I’m not the only one who appreciates the series, as it has placed in the Top 200 Finalists of the 2023 Critical Mass competition and an Honorable Mention in the “Non-Professional” Fine Art Category of the 20th Julia Margaret Cameron Awards.

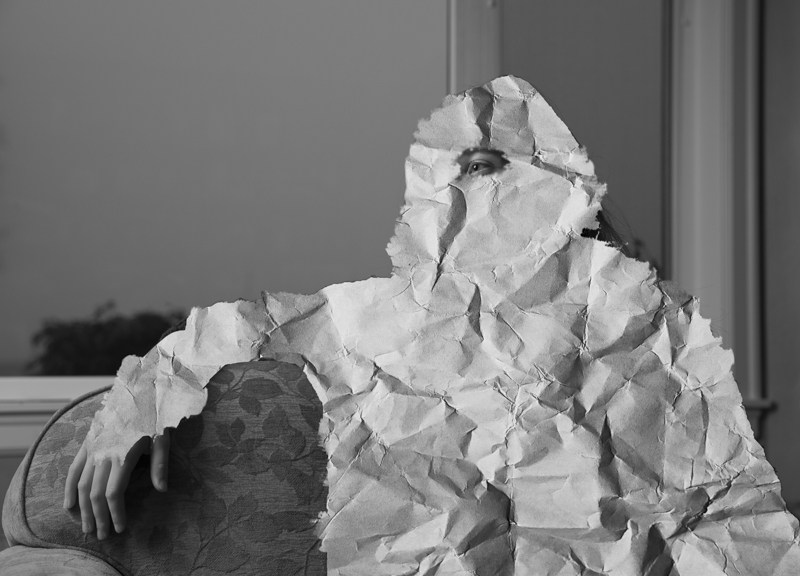

Janet Politte’s series Pandora’s Box considers the effects of clinical depression. She wanted to underscore that it is not simply a matter of “being cheered up and getting over whatever it is” but an affliction requiring medical care. Sometimes soul-crushing, the ailment can leave a person gripped by its clutches with distortions of reality that overwhelm them and prevent them from fully experiencing life as it should be. Politte worked with the metaphor of a veil between those suffering from clinical depression and those who have never experienced it. Her use of barriers to illustrate the isolation and entrapment that envelop a person suffering from depression immediately spoke to me. As someone looking from the outside, I thought the photos successfully showed how the experience of clinical depression might feel and how smothering it could be.

Geri-Ann Galanti turns the male gaze on its head with her series, Dreams of Sepharad. She drew her inspiration from Orientalist paintings, her Sephardic Jewish ancestors, and belly dancing (which has always been part of her life.) Galanti photographed the women in Spain, the land of her ancestors. The images depart from the Orientalist painting tradition of women presented as exotic male fantasies, instead imbuing the dancers with the power and beauty of their femininity. That makes the work distinct from the referenced paintings depicting eroticism and passivity. The female gaze is alive and well in this work. The images are sensitive and tender.

I had some familiarity with Elizabeth Bailey’s work before meeting her at the portfolio review, as we had occasional interactions via IG comments. Bailey is someone whose work always left me saying, “I wish I made that,” but I had not seen her work presented as a series, which was the way I saw it during the review.

When Bailey’s neighbor, whose home was just feet away from her own, seemingly disappeared, she learned the neighbor had passed on, reclusive and without friends or family. Curiosity overtook her, and the silent home became a personal obsession. The House Next Door is a story of both Bailey’s quest for knowledge and understanding and the next-door neighbor’s mysterious life. I saw the images before the review started and laughed out loud at the picture of Bailey going through the window. I had to ask whether that was a staged shot. It wasn’t; that was how Bailey entered the house. Bailey’s work is beautiful, a little quirky, and ambiguous. Bailey told me, “As the neighbor’s story intertwined with my own, I felt both gratitude and a deep sadness for all that was lost. I’d hardly known her in life, thinking our differences were insurmountable. Now I wondered, were we so different, after all?“

Some of the images from this series are in a traveling group exhibition, Memory is a Verb; I urge you to see the work in person should you live close to one of the venues.

Karen Duncan Pape visited Japan when she was finding her way back from what she termed “calcified grief.” While traveling, Pape concluded that nature and humans carry equal weight, both part of a vast continuum, inseparable. I’m not afraid to say that I don’t fully understand what she is saying with that thesis. I’ve not been to Japan; perhaps the statement would take on greater clarity if I had been. Yet, without understanding it, the two images of hers I’ve included here said something zen and elegant about the experience of being a viewer of the landscape while the landscape observed us.

While I am generally not a fan of reflection photography, Karen Numme is in love with it. I am always looking for concepts and feelings rather than observation alone, and for me, literal reflections are more about seeing than feeling. Numme holds an entirely different view and finds feelings and observations in reflections. She stated, “Reflections often symbolize introspection and looking to the past.” Numme told me she uses reflections “as a metaphor for the layers of her experiences,” which she feels gives viewers a chance to reflect on their personal memories.

This particular image of Numme was taken staring out her window while recovering from surgery. I gravitated most to this because, with the pandemic in our recent past, many of us spent too much time encased behind our walls and windows. I see this image as sad and whistful, while for Numme, the image sings of healing and recuperation, both physically and emotionally. It’s funny how one picture can say such opposite things depending on who the viewer is. Art generally resembles life, and differing interpretations are certainly part of living.

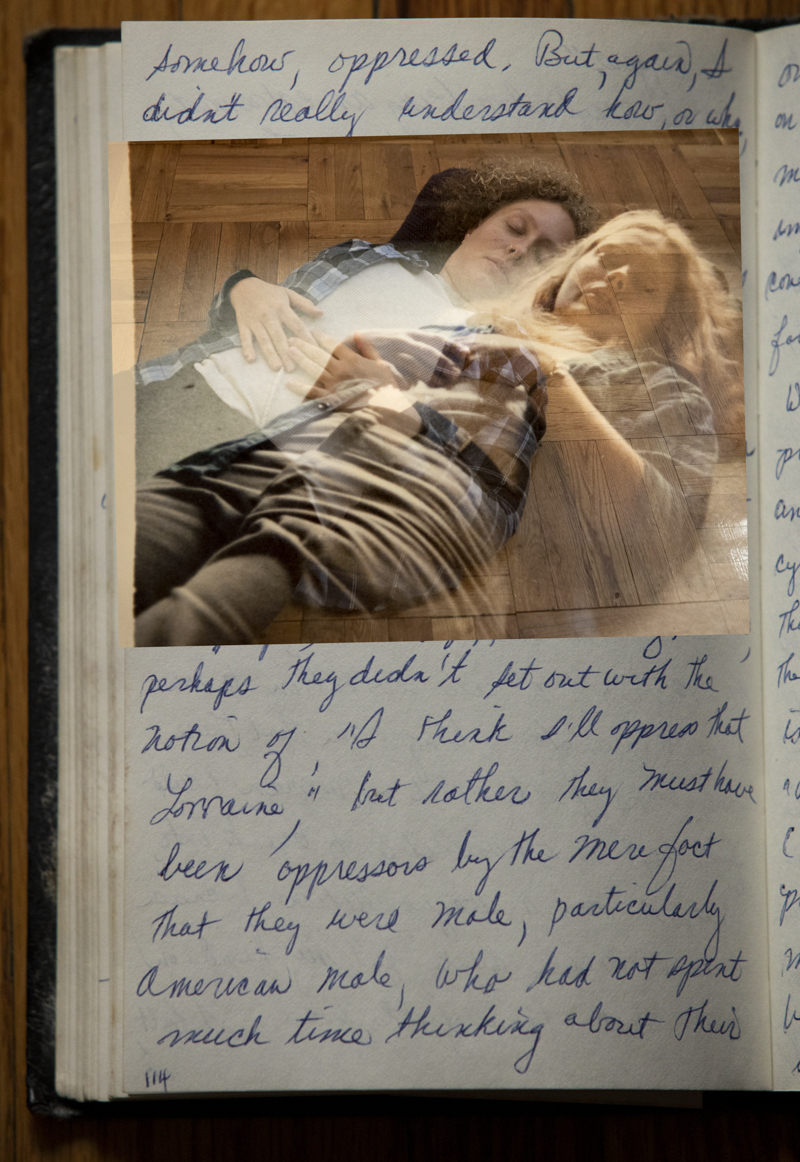

Erika Kapin celebrates the human experience by making vulnerable, intimate work to show her belief that regardless of our views and experience, “we can recognize our own experience in other people’s stories.” Some of her work is humorous, some serious, but all of it has considerable heart sunk down in the middle.

Kapin lost her mother at age 18. Kapin is 42 now (though you could have fooled me), the same age her mother was when she passed on. Mom and Me is an ongoing project that began during the lockdowns of the pandemic, a time when Kapin thought much about life, loss, connection, and the past. She spent some of the confinement reading journals her mother had kept throughout her adult life. Mom and Me brings together the photographs of her mother composited with those of herself and objects and journals from her mother’s life. The image I show here was the first Kapin made; her project has taken a slightly different turn, including Kapin making some stop-motion videos of the composite works. But this image, for me, told a complete story of two people’s lives intertwined, even if I did not know their personal stories. I will be watching to see how Kapin pushes this project moving forward.

I hadn’t seen or heard of this work before the review, but I fell hard for Safi Alia Shabaik’s series, Personality Crash. I was instantly reminded of Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember. How had I missed such terrific work before now? Shabaik’s work slugged me in the heart and just kept coming at me. I might have even had a good cry later that day thinking of it. The imagery is intimate, unflinching, tender, and incredibly well-crafted. I rarely print people’s entire artist statements, but this story is far better told in the maker’s own words, so here goes:

“Personality Crash: Portraits of My Father Who Suffered from Advanced Stages of Parkinson’s Disease, Dementia and Sundowners Syndrome explores the human condition when altered by disease from an intimate perspective. The work presents my family’s personal story but also serves as a universal reminder of what it means to be human.

In 2013, during the early stages of his Parkinson’s diagnosis, my father and I agreed to make this body of work as a way to bring us closer together, knowing illness would eventually pull us worlds apart. Our collaboration stemmed from a heartfelt desire to understand disease, mental illness, and loss of self. With my role as a documentarian and eventually primary caregiver, we created this work for a handful of years, through compounding afflictions of dementia and sundowners, until his death on January 1, 2018.

Ultimately, Personality Crash is an exploration of loss – my father’s loss of autonomy and self and my own loss of the father I had known my whole life – but it is also about family bonds and the power of love in the face of adversity. He had been my protector, champion, and role model, who seemed indestructible in his daughter’s eyes. As much as it gave me a window into understanding his physical and cognitive changes, this project gave my father strength and resolve. It gave him daily purpose – something to look forward to – and kept him engaged. It came to represent his own survival, though in reality, we were chronicling his demise. In his final year, my father had increasing moments of confusion, hallucination, disorientation, and major disconnect from simple instruction and the tactile world around him. My father became my child for whom I cared, protected, and advocated. I literally parented my parent and would go to all ends to guarantee his visibility and dignity in the world.

In retrospect, this project is bigger than either of us and more than just a bridge between our different realities on the road to my father’s death. The New York Times featured this work, calling it “raw and emotionally fraught” and the photographs themselves “powerful in their honesty.” From the beginning, we agreed to present an honest, vulnerable, compassionate end-of-life story to honor his journey. We wanted to humanize the experience of losing one’s sense of self while aging with disease. Through this collaboration, I came to new understandings of disease and mental illness, distinguishing the disease from the individual and the process of anticipatory grief. It was an unexpected lesson in learning the depths of my own capacity to love as well as the profundity of my anguish. My father was very proud of this work (as am I) and was an active participant up until his last day.”

It’s easy to see why this work has earned much recognition, including four solo exhibitions in 2023 alone, being named a 2022 Critical Mass Top 50, and garnering an NEA grant.

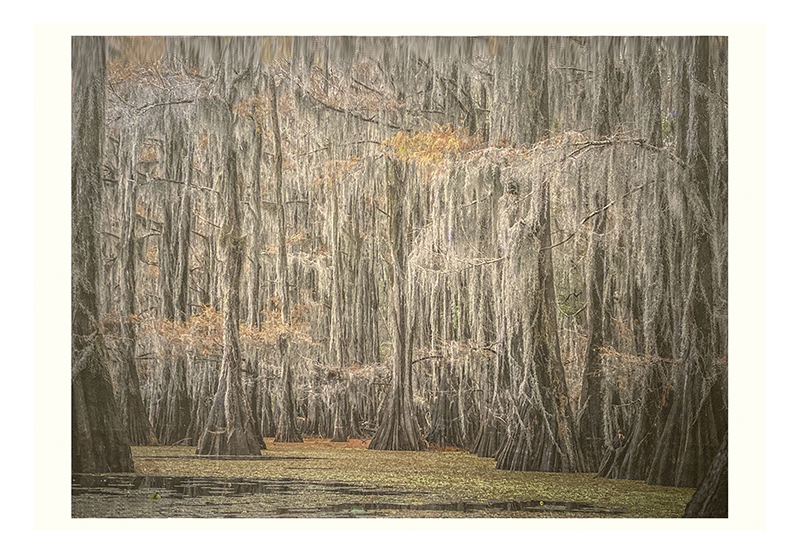

Frances Williams and I use both traditional media on top of our photographic prints, but Williams’ imagery is about 180 degrees removed from my work. Williams ventures into the wetlands, often in the wee hours with headlamps for light, to photograph wildlife in its natural habitat. Yeah, now you know why I said it could not be more different than my work. Although wildlife is not a subject that calls to me personally, I was taken by how masterfully Williams uses pastels and other traditional media atop her prints. Even though we met on Zoom, I could recognize the hand coloring long before she told me of it. I’ve selected one of her works, a pure landscape scene, since critters and I are not kissing cousins. The day she took this image, she was out in the cold water before dawn, an experience she related as “otherworldly.” This work also has a back story best told by the person who lived it. Williams told me, “On the surface, the scene looks like a beautiful, natural landscape in a quiet, serene environment. (But) Giant Salvinia is invading the area and choking the life out of the waterways. This floating weed displaces desirable native aquatics that waterfowl feed on. It also creates a shading effect for submerged aquatics needing sunlight. It damages native ecosystems by destroying native plants that provide food and habitat for waterfowl and native animals, thus turning areas into biological deserts. Over 1 million acres of wintering waterfowl habitat of Cypress Tupelo Swamps have been affected, as have other waterways throughout the South.” Williams prints on sheer, delicate Japanese papers to highlight the fragility of the ecosystems she documents.

When I saw this image from Katherine Mikolajczuk in her PDF before the review, it left me curious about what I was looking at through the condensation. I speculated it was bare plant life in a winter’s snow. The window itself is oddly framed, unlike any I had ever seen. I kept coming back to this image to look further. None of my guesses were close. Mikolajczuk said, “This image came about the day I toured London with my husband and kids. We were walking past this incredible room with an old window that just happened to be visited moments earlier by a little child. I never saw them but they left behind their little hand prints on the steamed up glass. I loved the mystery, the moodiness and the non permanence of that moment.” Aha! The shapes I thought of as plants were a toddler’s handprints on the frosty glass. Once she said the words, I immediately saw it, but not before that, which made it a quirky and curious viewing for me. Mikolajczuk said, “We are in a constant state of living and dying, existing in a fragmentary world, never really seeing the full picture. I feel honored to expose the beauty of these ephemeral treasures that I happen upon as I move through daily life.”

The importance of Beth Burstein’s work, The Legacy, is undeniable. Burstein is the child of a concentration camp survivor. Given the extreme increase in hate crimes, anti-Semitism, and white supremacy, there is no better time for the reminder of what we need to prevent from happening again. Not just here in the US, but this backward shift seems to be happening internationally, likely everywhere the authoritarian governments sense an opportunity to spread fear and division among people who got along just a few years back, destabilizing democracies globally. The heirloom in question is the concentration camp uniform her father had been issued as a teen before the camps were liberated.

Burstein writes, “I am the daughter of a Holocaust survivor. I never knew my father’s parents, his sister, or aunts and uncles. At the age of 44, in 2005, I visited Lithuania where my father was raised. Until then I could only imagine it through his stories, the three family photographs his father managed to keep safe during their concentration camp imprisonment, and my father’s concentration camp uniform, which he brought with him to America. Although I have always known his Holocaust history, his story unfolded further as I grew older and my questions became deeper and more probing. The Legacy was exhibited in educational and community center settings until 2015, allowing me to share my father’s Holocaust story, my experience being 2G (Second Generation), and how genocide and trauma can affect future generations. With the recent, alarming rise of anti-Semitism in our own country, I feel an urgency to resurrect and re-purpose this project to spread Holocaust awareness and combat misinformation.”

Alexandra DeFurio makes work after my own heart. Both the projects she showed me resonated intensely for me because the work was deeply personal, cathartic, ‘pour your soul and your troubles out into the project’ type of works. It’s poignant, beautiful, and melancholy. These works use the language of photography I most enjoy and what I gravitate towards making myself. I just GOT this work – all of it.

I’ve selected an image from both projects she showed me. The first project, Fault Lines, uses a metaphor of fault lines beneath the land. She said, “Living in California means you could have a fault line running through your backyard, in any unforeseen moment, an earthquake could hit, and your home could fall to complete destruction around you. The fault lines in our lives are much the same, building pressure over time until one day there is a shift in the foundation, and within a few moments – perhaps through a phone call, a few words uttered – we are given a diagnosis, a relationship breaks, or someone we love dies, and the life we knew before is lost in the fallout.” After her mother passed from Alzheimer’s concurrently with the loss of a long-term relationship, DeFurio felt the fault lines trembling beneath her. Her sense of abandonment brought her out to explore abandoned houses within her neighborhood, camera in hand, seeking out the healing within the wreckage. She’s seriously braver than I would be; I cannot imagine wandering onto strangers’ property in a city like Los Angeles.

Her second project is called January. After a year of significant losses, DeFurio chose January 2019 as a month where, upon awakening, she would make one creative self-portrait per day, using only a tiny space between her bed and the white wall as the stage. She states, “Within this limited physical space and the expanded consciousness present upon waking, I explored the duality synonymous with the beginning of the new year, a time of reflection and letting go of the past, while planting seeds for the new. Day after day, I confronted myself in the lens and a visual journal unfolded. A witnessing of self during transition, a personal story of darkness and light, hope after loss, letting go while holding on, the power of the feminine, and the emergence of a brave new self.”

Eleonora Ronconi resides in California but currently splits her time between there and her native Buenos Aires home. During one of her trips home, she decided to photograph things she missed that she considered an essential part of her life.

She wrote of this project bringing life into focus again, yet, “Just as I started this reconstruction of time and place, my aunt was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. When I told her about my project, she told me how much she enjoyed photography when she was young and with tears in her eyes, she said ‘I am so happy you decided to photograph your home and collect your memories, because I am losing mine… so go out there, see for me, remember for me, you shall be my eyes’. As she slowly forgot who she was, I remembered who I am. This journey allowed me to rediscover the universal quest of self, collecting the pieces that had been left behind and occupying the spaces that had been left vacant.” Her imagery is beautiful in a forlorn manner; her attachment to the items photographed came through the imagery.

I hope you enjoyed this peek into my experience reviewing portfolios for LACP, and will further explore the work of the photographers whose work featured here you enjoyed. Most have website info below their bios.

Thank you to all the artists for allowing me to present your work to my readers.

ARTIST BIOS

Robin Bell is a New York-based photographer whose projects are studies of one place and can go on for years. Her interest is in abstraction and illusion. Bell’s work has shown nationally and internationally, and her work has been profiled in several publications. Her series “One Pool, Los Angeles” is a Top 200 Finalist in the 2023 Critical Mass competition.

Janet Politte is a visual artist based in Bellevue, Washington. She started her photographic career late in life but considers it to be her vocation. Janet works with film, digital and alternative processing. She is excited about combining the modern processes of digital capture and manipulation with the hands on alternative processes and everything in-between.

Geri-Ann Galanti is a portrait photographer, specializing in timeless images which evoke a distant time or place. Her skillful use of lighting, costumes, and props create dramatic and vibrant images. A devoted fan of time travel fiction, she’s able to apply that love to her various photography series, along with her lifelong passion for playing dress-up.

Elizabeth Bailey is a Los Angeles-based photographer who explores the themes of self, identity, memory, and longing. She uses staged scenes, portraiture, and self-portraiture to consider what we conceal and reveal about ourselves to others. Her work has been exhibited in museums and galleries nationally and internationally, published in books and magazines, and is held in private collections.

After retiring from a business career, Karen Duncan Pape has devoted herself to her first love, photography. She has had numerous shows, Including “Songs of Africa” at Speak! Language Center in 2020, “In the Deep Heart’s Core” at Chroma Arts Laboratory in 2023, and an upcoming show, “De-circulated,” at McGuffey Arts Center in 2024. Her work has been exhibited in numerous exhibits in the Praxis Gallery, Minneapolis, D’Art Gallery in Denver and Norfolk, VA, and the A. Smith Gallery in Johnson City, Texas.

Karen Numme: Born in the Bronx. Spent many years living in cities on the east coast, before settling in Los Angeles. I graduated from Harvard University with MLA degree, a M.Arch degree from UNM and Art degree from Parsons School of Design/NYU. Over 10 years ago photography became my medium of choice. My work has been exhibited Internationally and, in the U.S.

Erika Kapin: Born in Seattle, Washington, Erika moved to NYC in 2005 where she received her BFA from the New School for violin performance in 2010. Erika has studied and worked as a teaching assistant at the International Center of Photography. Currently living in New York City, Erika continues to work on her personal and professional projects in creative portraiture and documentary photography.

Safi Alia Shabaik, known by her moniker flashbulbfloozy, is a Los Angeles-based interdisciplinary artist working in photography, collage, sculpture, and experimental video. Her photographic work explores identity, persona, transformation, daily life, and the humanity of all people; her subject matter spans the self, family, street life, fringe, and counterculture. She exhibits her work nationally, has been featured in various publications and podcasts, has earned recognition in Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50, and has received a visual arts grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. A lover of the human form, she is also an award-winning mortician.

Frances Williams is a visual artist that grew up In New Orleans, Louisiana with a deep respect for nature. She spends a great deal of her time photographing sensitive, threatened environments and then prints her images on archival Japanese rice papers. Multiple layers may be added before printing and then she hand colors using a variety of mediums. Each image is one of a kind, enhanced in her minds eye, to show the beauty of the environments depicted.

Kasia Mikolajczuk is a Polish-born photographer living and working in Los Angeles. As a child growing up behind the Iron Curtain, she learned to observe ordinary objects with curiosity. Her work reflects that sensibility in its abstraction of life’s day-to-day moments, capturing ordinary objects in a state of transition from usefulness to ruin.

Beth Burstein is a photographer based in the New York City metropolitan area whose work currently focuses on projects recording vanished or vanishing cultures. Most of these projects stem from her own history and experiences, and her desire to tell these stories, which she feels hold a universal connection. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibits nationally and internationally.

Alexandra DeFurio is a Los Angeles-based artist. Her personal narrative work explores themes relating to female identity, loss, and memory. Her creative process includes cyanotype printing, self-portraits and double exposures. Her work was recently shown at the Milan Photo Fair and published in Lenscratch, Shots Magazine, and What Will You Remember?

Eleonora Ronconi was born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina. After spending almost three decades living in the United States, she now divides her time between California and Buenos Aires. Her work explores ideas of memory, family and the perception of home, based on her experiences as an immigrant with a ties to two worlds. Her photographs have been exhibited in several solo and group exhibitions worldwide, and they can also be found in museums and private collections.