Jari Poulin is an artist and printmaker using photography as the main expression of her practice. She lives in Ithaca, NY. She holds her MFA from Lesley University College of Art and Design (formerly the Art Institute of Boston). Ms. Poulin is the recipient of many national and international awards, including the International Photo Awards (IPA), 15th Annual Julia Margaret Cameron Awards, 7th Worldwide Pollux Awards, Moscow International Foto Awards (MIFA), Prix de la Photographie, Paris (PX3), International Color Awards, ND Magazine Awards, Black and White Magazine Portfolio Award Winner, Color Magazine Portfolio Prize, the Ink Shop International Mini Print Juried Exhibit and has been published those affiliated magazines and online galleries. Her work has been exhibited widely, including the Barcelona Foto Bienniale, ClampArt Gallery NYC, Praxis Gallery, Gallery 1202, the Bower’s Museum, C4FAP, Galerie de la Ferme du Mousseau, Elancourt, France, as well as in Limerick, Ireland with the Ink Shop Printmaking Center, Griffin Museum of Photography, John Wayne International Airport, Atlanta International Airport, Atlanta Photography Group, PhotoPlace Gallery Vermont, the Lunder Gallery in Boston, SE Center for Photography, Cape Cod Center for Photography, and various galleries in Taos, NM, NYC for the Story of the Creative Exhibition, See Me Year in Review Exhibition on Long Island, The Ink Shop Printmaking Center, State of the Art Gallery in Ithaca, NY, and in many venues throughout the Finger Lakes region.

In 2019, while attending the Photolucida Portfolio Review, a woman I did not recognize stopped me and said something close to “(NAME) told me she is having dinner with you tonight. We are roommates at the hotel. I’d like to go, too.” She told me her name, Jari Poulin, and I realized that we were vaguely knowledgeable of each other through FB and had planned to try to meet, so this was somewhat fortunate that it happened.

In retrospect, I can see why we became friends that evening: we have similar life views, both do traditional printmaking, and love blur! But after reading her responses to my questions here, I realized how we think about making work, and our approach to creating is quite similar despite the sometimes difference in our work’s content or idea. It’s been incredibly energizing for me to learn all this about Poulin’s work, and I hope you all find her as inspirational as I do.

DNJ: Tell us about your childhood. What was your family life like? What did your parents do? Do you have siblings? Was anyone else in your family an artist or photographer?

JP: I grew up in Lakewood, NY, a small town on Chautauqua Lake in the southern tier of NY close to the PA border, with two brothers on either side of me. We were in the snow belt, and winters were always full of great outdoor fun, snowball fights, snowmen, skiing, and skating on the lake – and we had to shovel our own rink to do that.

My mother was a single mom who struggled to raise the three of us, but she always made sure we had opportunities. My little brother took guitar lessons, my older brother was into sports, and I took dance lessons. We all had an interest in music especially. My father was a musician but often lived in California, and we didn’t have much time with him growing up. My great-grandfather Arnie lived with us when I was a child, and he was my best buddy. He loved photography and would show me how to use his old camera. He also had a stack of 78 records and would teach me dances like the two-step and share rare music like cowboy poetry.

DNJ: What were you like as a child?

JP: I was a dreamer, and I still am. I enjoyed anything involving play acting, dancing, choreography, costumes, and dreaming of other people, places, and roles I might take on. That is what has always driven my art.

I always wanted to bust out of wherever I was – a true wanderer and explorer.

My mother said that when she took me by train across the US as a toddler, she had to tether me to her because I had no fear. I would walk away, talk to anyone, sit with them, and want to see everyone in the train car. I tried to leave the train car through a connecting door and get on another car, which was the last straw.

I’m still a bit like that. I love to dance, theater, poetry, literature, photography, and fine art. It allows me to keep moving, figuratively speaking, to transcend my present experience and experience something entirely new and exciting. I’m in my element when I’m learning and doing. Being a maker and a creator has given me that.

DNJ: When did you take your first photograph? What was it, if you remember?

JP: I took my first photograph with a Kodak Instamatic that I got for Christmas when I was around 10. It was in the backyard. My Grandfather, Arnie (who we called Pappy), gave me that camera. At his suggestion, I spent the roll doing a photo essay of my backyard world: the apple tree, the garden shed, Arnie’s rhubarb patch, the Willow tree in the neighbor’s yard, and the burning barrel (back then, people in our neighborhood actually still burned their trash).

DNJ: When did you figure out art was your career path, and how did that happen?

JP: I had a circuitous path to a full-time career in photography and fine art. I was a dancer, choreographer, and artistic director of a regional ballet company. After having my first spinal surgery at age 34, I continued teaching for a while and then served as Executive Director/CEO of a few dance organizations in Boston before finally realizing I needed to give my soul what it needed: to be a full-time creative.

Photography had been my passion since high school (I spent untold hours in the darkroom under the tutelage of an incredible teacher, Tom Prohaska), so I decided to pick up my camera and start making work and to write with equal zest to feed that creative drive. To achieve this kind of transition from my work life in Boston, I gave myself a year to figure out how to do this. I moved to a small fishing village in Mexico and focused on making photographs and writing. To help with financially supporting myself, I did some long-distance consulting with non-profits. Afterward, I moved to Taos, New Mexico, and started a full-time photography career.

DNJ: If you weren’t an artist, what career would you want to pursue instead?

JP: I have a genuine love and appreciation for neuroscience that began when my daughter experienced an anoxic brain injury at the age of 17 that caused her to require four years of cognitive rehabilitation. Throughout those years and those that followed, I read books about the brain, neuroplasticity, and cognitive rehabilitation, searching for answers to understand what had happened to her and how to help. I find the breakthroughs in neuroplasticity (the ability of the brain to find new ways of reorganizing and functioning when certain areas of function are lost) fascinating. I would research what people were doing with therapies that can rebuild new synaptic connections. Through my experience with my daughter, I learned that I might have a passion and ability for scientific thinking. It is more like art than I had previously thought because it requires creative thinking, observation, and experimentation.

DNJ: Where did you go to college? Did you study art?

JP: I studied dance at Virginia Intermont College but left my senior year to be with my mom when she was diagnosed with cancer. I finished my degree in Dance at SUNY Fredonia through independent study. I have my MFA in Visual Art from Lesley University, a great experience where I learned to challenge myself more aggressively. The MFA program allowed me to place my work in the context of the historical perspective of photography, the broader scope of visual art, and my relationship with all the artists who have come before me.

Throughout my adult life, including all those years in Boston, I took many workshops in alternative processes, darkroom techniques, photography, lighting, studio work, fine art, poetry, and more. I’m a life-long learner.

DNJ: Who are the artists who have most influenced you?

JP: Honestly, there are so many, and every artist ever has influenced me in one way or another. I studied art profoundly in my teens and early 20s and absorbed the likes of Vermeer, Renoir, Michelangelo, Da Vinci into my blood. They were my favorites. In photography, Lillian Bassman was my queen because of her brave quest to disturb the imagery in the darkroom and her use of blur, which I love to use because it equates to motion! She rocked the boat of fashion photography and was a disrupter. I love that she was a female disrupter when few females were in photography, particularly fashion photography. I also love Irving Penn and seeing his work permitted me to be playful. My all-time favorite artist ever is Gerhard Richter. He was an artist without boundaries in his art-making and a true explorer.

DNJ: How much of your art practice is photography?

JP: With a rare exception, everything I make is photo-based and generated from photographic ideas and material. While some of my work is straight photography that is output to various papers and substrates, in other work, I take my images into the printmaking studio and combine images with textures and backgrounds that I make with collographs, monoprints, and sometimes collage. I often use various photo transfer techniques to achieve depth and layering. I like the handmade. Looking at work and feeling its physicality is very important to me. That is one reason I don’t particularly appreciate looking at work on a computer. It is only possible to understand the presence of the work if seen in person. In the past five years, I have begun to use photographic images as the basis for 3D work and have made large and small installations that include block sets, magnets, and various constructions.

DNJ: Why combine photo and printmaking? What does the combination do that one alone cannot?

JP: I grew up in the darkroom and watching the magic happen on so many levels, not only in the darkroom trays but in the magic of developing negatives and contacts sheets and seeing/remembering what I caught on film and tweaking it with burning and dodging and chemistry. So when I converted to digital in the late 90s, I quickly became disenchanted with sitting for all those long hours in a chair learning Photoshop and Lightroom (I was a Beta user). I loved the new options I had, the new kind of magic I could create, but I HATED sitting still. The dancer in me could feel my metabolism slow down to a snail’s pace from not moving enough, and my back hurt from all the sitting. So in 2010, I took a workshop in Solarplate with Dan Welden, master printmaker and pioneer of non-toxic polymer photogravure printmaking. Dan showed me the magic of the print reveal after you ink a plate, cover it with fine art paper, and run it through the press, and you slowly lift one corner back to see that gorgeous ink uncannily embedded in the paper. I was moving again to do my work and hooked on the singularly fascinating quality of ink and paper and the tone variances you can achieve in making and inking your plate. I still have the same excitement with this process as when I saw my darkroom prints appear in the tray before my eyes.

That was the beginning, and then I took more printmaking and alternative process workshops from great mentors like Dan until I was ready to set up my darkroom and ink shop, which I now have at my studio. I incorporate Solarplate and other photopolymer gravures, monoprints, photo transfers, collographs, collages, and hand coloring. I also learned a lot from books and experimenting on my own.

Why? There is something so special about handling and touching the materials, inking plates, mixing transfer solutions, and putting my hand to the work. Dan was the first to encourage me and help me understand that printmaking should not begin and end with the image and that I should “show” my hand and make my marks. It gradually dawned on me that this would allow me much freedom to alter images, add context and meaning, and expand my ideas.

DNJ: What challenges do you face as a photographer?

JP: Aging. I just underwent two major spinal surgeries–a result of all those dancing years and the resulting spinal stenosis and arthritis that impedes my spinal cord. I’ve had to work on tripods more and more, hire assistants to carry equipment when I need it, and now I need to manage the physicality of my day with stretching, physical therapy, and resting when needed. It’s hard for a go-go person like me to slow down and make more considered choices about what they do with their body, but I’m finally learning.

DNJ: Do you always have a concept when you start a project or do you shoot and allow the images to tell you what the project that emerges will be?

JP: Yes, my work almost always starts with a concept. It’s a holdover from my days as a choreographer or simply how I best work. The concept initiates play around a theme. I start with sketches and journaling my ideas. I like to play with possibilities, so I sketch or write about various ways I could approach my concept. I also research what other people have done around a subject throughout history to be aware of the legacy of ideas behind or adjacent to my own.

DNJ: To help familiarize readers who may not yet know your work, could you briefly explain the various series?

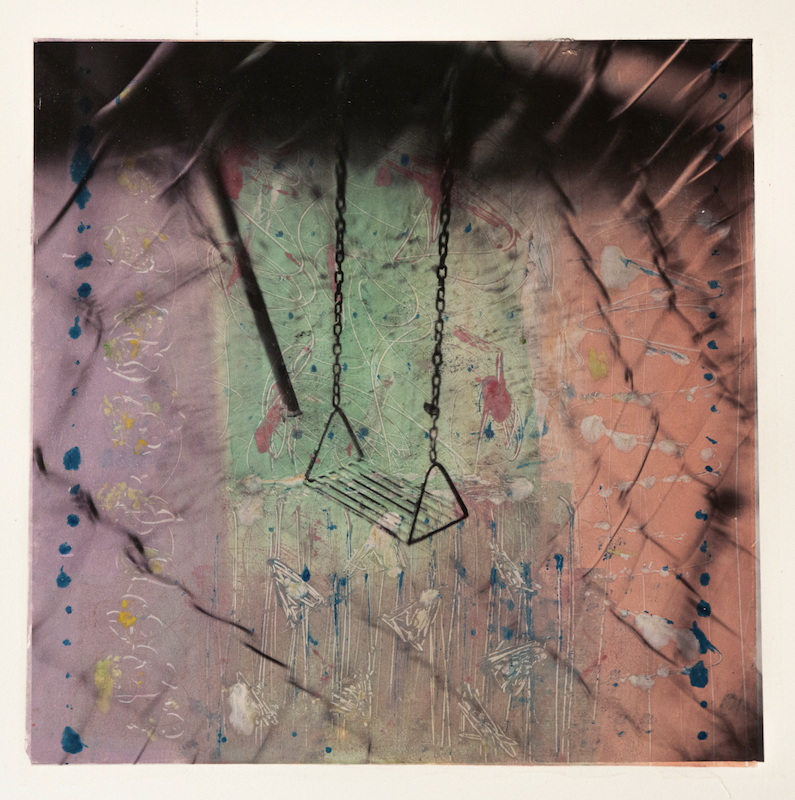

JP: Mirage (2022) features images combining monoprints and black-and-white photographic transfers to create dream-like worlds that speak to Memory and imagination. It integrates my fascination with optical illusion by combining ideas of specific places and people of my past. In these images, I am recreating the way the Memory feels as if it were a mirage seen in my past. As time passes, memories can feel like mirages – like fantasy or illusion—and can leave us questioning if it was real.

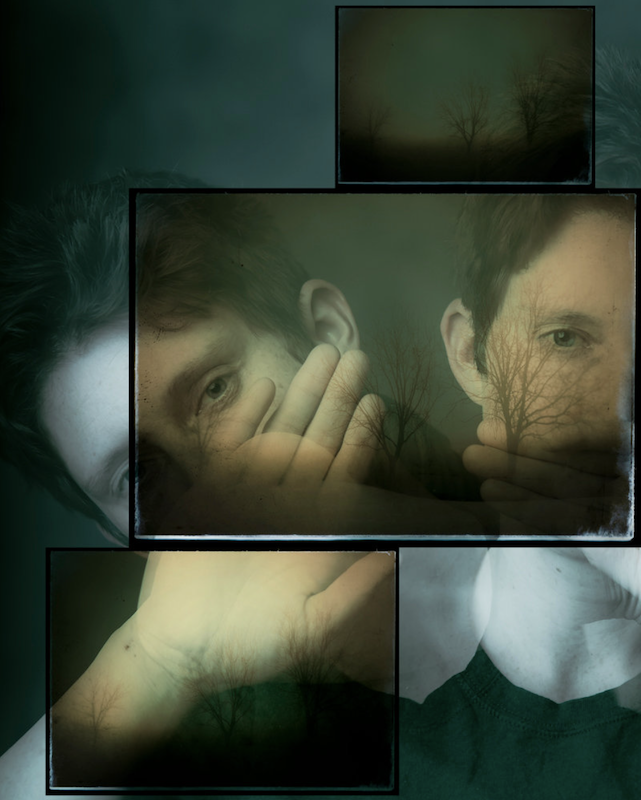

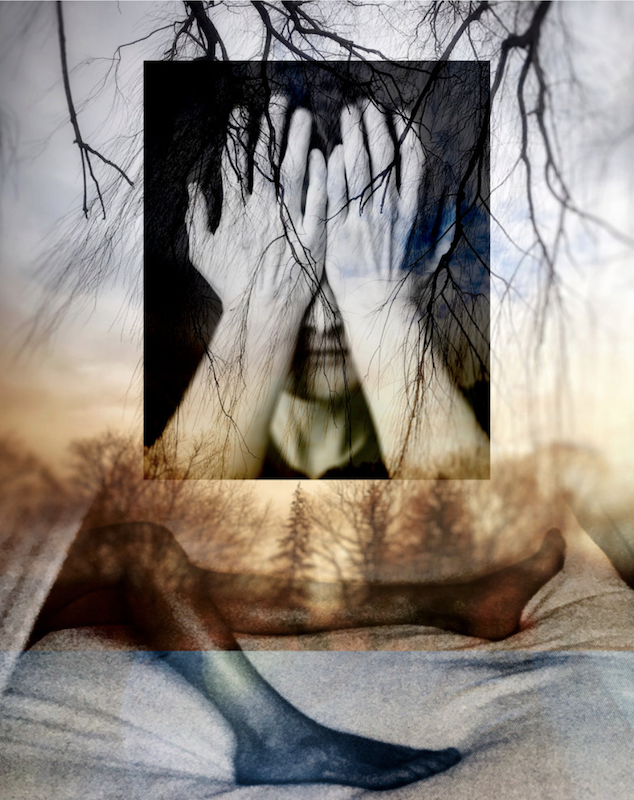

Breaking Point (2021) builds on the work of my earlier series, “Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil.” It explores the diminution of women through the subtle yet insidious silencing of women in the workplace, relationships, and social settings. This silencing is a pervasive social construct that causes many women to feel uncomfortable expressing themselves and asserting themselves in life and work. This silencing continues to perpetuate through family, relationships, and religious cultures, as well as social conditioning from the earliest ages with exposure to digital devices, social media, educational systems, and social circles.

Senses in Animate Objects (2020). These are the images of the objects and subjects used in the Senses in Animate portraits. I have developed notions of these images within the context of digital editing landscape to contrast the inanimate nature of objects and the animation of those objects as subjects activated their senses via these items. I am exploring the contrast between a whole sensory experience vs. one that resides mainly in the mental, visual, and digital sphere that envelopes our lives during this digital era.

Senses in Animate (2019-20) is a portrait series that explores and celebrates people engaged in activating one or more of their five senses. I have acute senses that sometimes overwhelm me with intensity and even a sixth sense that is quite significant. This project allowed me to make portraits of subjects with overlapping reactions to things that excited their senses. What was most exciting to me in this project was the seconds between frames when I could capture some exquisite stillness in each individual. At the same time, they were unaware of the camera during these multiple exposures. I consider it the “stillness” of the “interiority of being.”

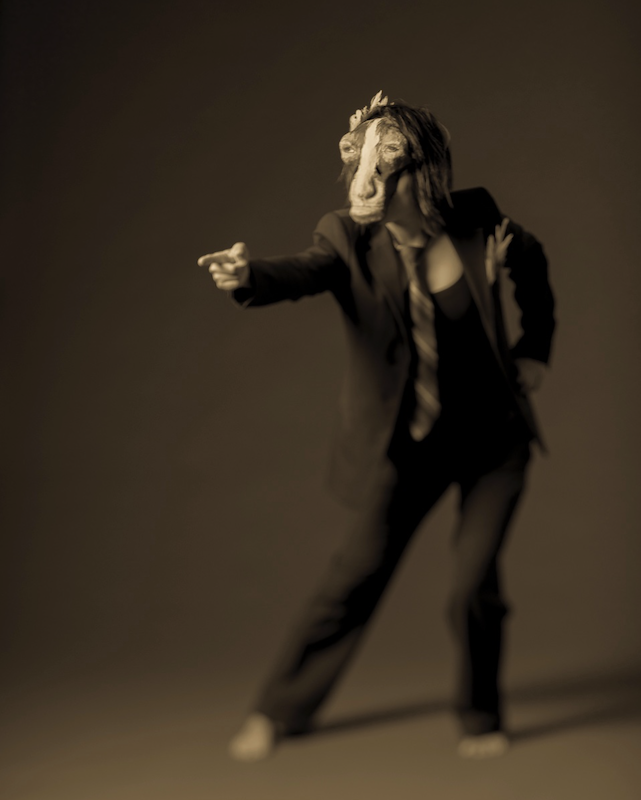

Speak, Hear, See No Evil (2017-18). At the dawn of the #metoo movement, I was struck with how women of all ages have been conditioned to keep quiet by the forces of both men (and other women). These forces continue the patterns of social conditioning that silence women in numerous ways through shaming, blaming, and making us believe our voices are uncouth, too loud, or that society will shun us if we talk too much about experiences of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or the reality that from birth we are subject to tremendous amounts of mass and social media that condition females that to be “man-pleasing” and to be sexually desirable. This series reflects my concern with these issues through the western interpretation of the Japanese Three Monkeys who hear no evil, see no evil, and speak no evil. With their hands over the eyes, ears, or mouth, the body language suggests turning a blind eye. Whether the intent is reluctant, painful, or permissive, it perpetuates the harm being done to women by not acknowledging it.

I Am (2015-17) is a direct result of a collaboration with six dancers who agreed to explore and share aspects of their core identity, alter ego, and secret identities with me over several months through an interview and developmental process. I was interested in making images of dancers portraying their power instead of assuming roles dictated by a choreographer, as is typical in a dancer’s life. I was also interested in the cathartic power of considering, putting into words, and honoring aspects of their identities outside their dominant dance identity through the following image-making process.

#metoo (2016-2017). President-Elect Donald Trump’s campaign shook me to the core as a woman, a human, a person of compassion, and a believer in good. His words were divisive, insulting, and disrespectful to women, non-Christian religions, non-white races, and even those with disabilities. The images in this series were initially imagined partly (sans political influence) to express ideas of how women, in particular, are portrayed in popular advertising, media, and culture. As the campaign evolved, so did my images.

Dance/Memory (2013-present). The work is very personal for me. I was a dancer and choreographer who left dance in my early 30s due to a severe injury and surgery. While dancing and choreographing, I often thought about how dance’s emotional and kinesthetic qualities might be captured memorably. This project allows me to explore these concepts through the scrim of memory while capturing the visceral and emotional beauty of dancers of all ages as they give the world a concentrated integration of body, mind, and spirit through movement.

DNJ: Sometimes, one project leads naturally to another, and other times a series is done, and there is nothing left to say with a sister series. Where do the ideas you work with come from? How do they influence each other (if they do?)

JP: A project is born of a need to work on and develop an idea so that I can understand it myself and internalize its importance to my sense of identity or being or growth. My thoughts usually start with a solid connection to my experience. When I made Dance/Memory (still a work in progress), it was an enormous catharsis about personal identity and the loss of that identity.

When I made #metoo it was the beginning of a massive awakening about the continued plight of women not only in the context of sexual aggression, insidious domination, and the continued objectification of women but of the cultural and religious domination of women in countries where women’s freedoms are highly curtailed. I was opening my heart and mind to the sisterhood of sharing gender with women everywhere and what that means. Newer works such as Speak, Hear, See No Evil, and Breaking Point are related to concerns around women. Some even share imagery that was reworked for a new context. They are not necessarily a sister series but a thematic development. Breaking Point is a series in which I seek to introduce a more evocative dream-like state where symbols, multiple images, and visual debris can enter and interfere with the images to create some confusion and even wonder for the viewer. The photos in that series continue to grow and will soon be developed into unique pieces in the printmaking studio with a layered approach of inkjet prints coupled with transfers. My concerns for women, my daughter, and all the young girls the globe over have become something I continue to learn about and express in my work, but not exclusively.

DNJ: Are your projects straight shots, digital or analog composites, or mixed with both? How/why/when did you start altering the work?

JP: It depends on the project. For instance, Dance/Memory and I Am are all straight camera images, and all the portraits in Senses in Animate are all in-camera multiple-exposures carefully choreographed for overlapping effects. Many people assume these were made in post, but they were not. I loved the challenge of using my brain to imagine what choreographic queues I’d need to give my subjects to achieve the overlapping results I sought.

In the Objects portion of Senses in Animate, I was using irony and, of course, Photoshop. The concept of this project is that it is a nod to Photoshop with the checkerboard background and the vivid brush strokes and highlights. I wanted this portion to accompany the portraits in the exhibition to allow the viewer to compare the difference between the animate and inanimate, authentic human emotion vs. the staged object by itself. How is an entity different when it is held and reacted to?

In Hear No Evil, See no Evil, Speak No Evil, all the images are in-camera-made with multiple exposures. The Breaking Point series is all composite work in Photoshop. In the Mirage series, they are straight photographs layered with monoprints as photo transfers.

I alter work when there is a reason for doing so or a vision I want to share. I use the resources I have to accomplish the goal of my imagination, idea, or concept.

DNJ: Tell me about your typical work process.

JP: While every project is different, it all starts with an idea, a concept, something I want to dig into and learn about. I begin with ideas and develop those ideas by journaling and sketching. I research the idea through reading and internet searches and see what has been done in that area before me and what people are doing with those ideas now. I try to learn more about my subject matter and deepen my understanding.

If people are a part of my project, I start talking with them, meeting with them, and sometimes interviewing them. I enjoy the collaborative process with my subjects and want to bring their entire being into play. Then I make the photographs in one or many sessions, edit them down, keep revisiting them, tweaking edits, and distilling them to those I want to include in the series. I move slowly with this as my perspective changes over weeks and months. Sometimes I go back and photograph my subject again and again.

I make prints and begin taping them to the walls to see how they talk to each other. I ask people I trust for their input and reactions. I play with the prints in Photoshop and analog studio with transfers, plates, and ink to see what begins to work, but I leave LOTS of room for serendipity. When I hit on a combination of techniques or processes that really speak to me and expand my point of view, I go for it and begin taking all the images in the project into that working method. But this process of play and experimenting usually takes months and months.

DNJ: You work with different media within the realm of photography. How do you determine what media is the right one for any given project?

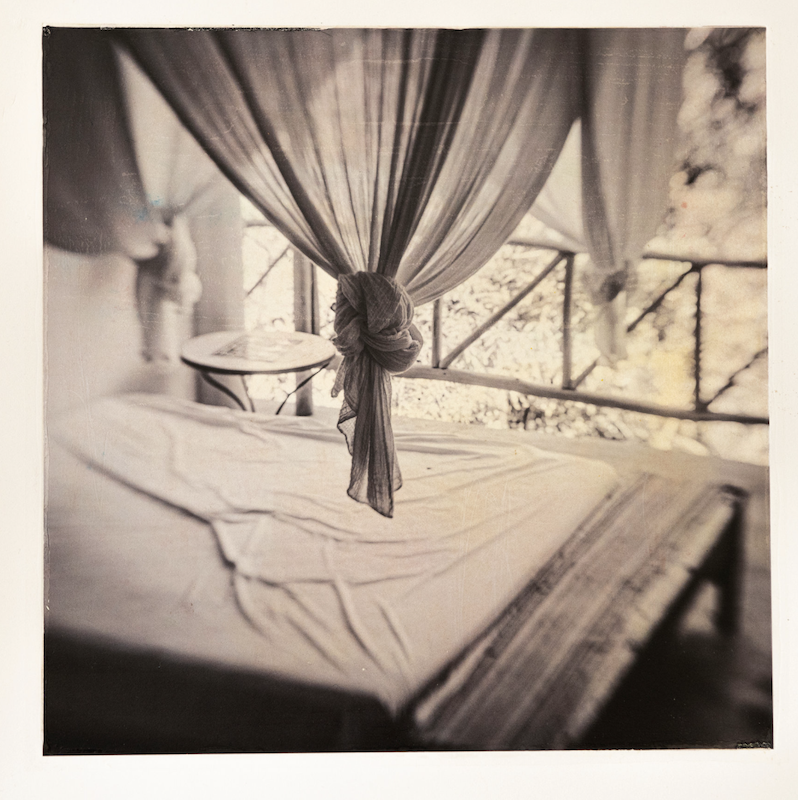

JP: Most of my projects begin with an idea of whether they will be strictly photographic or be taken into mixed media or printmaking. For instance, I knew that Dance/Memory, I Am, Hear No Evil, and Senses in Animate would be strictly photographic because I had visualized them as such before beginning the projects and had particular ideas of how to capture those images. In the case of Dance/Memory, I made a black box theater in my studio with a dance floor and worked with Lensbabies in the dark for months to capture the feel of blur, intimacy, and motion that I had imagined for the project. For Senses in Animate, I knew that the in-camera multiple exposures would create abstractions and a sense of movement and capture those fantastic overlapping facial reactions to the sensory stimuli. That was critical to my vision, and those images stayed in their photographic form even when I created 3D objects with some of them. With Mirage, the photos were never shot to layer with monoprints; that came later when I began thinking about how to describe the “feeling” I had in those places that I thought were still missing from the images – the invisible experience of being there and also of remembering that feeling in absentia the emotion of place.

DNJ: What is next on the horizon for you?

JP: I have much to look forward to, but I am re-entering slowly after a challenging year and trying to get my bearings. In the past year, I lost my little brother to cancer and have gone through two major spinal surgeries and recoveries that are just allowing me to get back to work. I am excited about a new series of symbolic photographic imagery combined with printmaking in panels. I am working with ideas about relationships between objects and humans and the fragmentation of self in an over-saturated world of information. I want to take the nugget of that idea and make it into unsettling but beautiful images. I am in the sketching phase of that work. I see this work as life-sized eventually, but I will start with small mockups, and some will be 3D. I’m also putting together a book of B&W images of Yelapa, Mexico, where I had a rebirth of sorts in the early 2000s. It is a place that has special meaning to me because it allowed me to reset my spirit and life path by tuning into the simplicity of life in a small village. I plan to include some of my writings and poetry. Also, I continue work this year on another book from the massive, multi-year project called Dance/Memory that I plan to finish by 2025. Additionally, I’m on my way to France to make monoprints backgrounds inspired by place and culture that I will use for photography that I will make there to signify my gratitude for the small wonders and little gifts in life.

DNJ: Thank you so much for your time. I’ve enjoyed learning more about your work, Jari, and I look forward to seeing what you do next!

JARI POULIN

Fran Forman

March 2, 2023 at 14:04

Thank you Diana for featuring Jari here on Frames. I had the pleasure of meeting her in France, and her talents and energy warrant our attention. She’s also a lot of fun and a wonderful teacher!

Diana Nicholette Jeon

May 28, 2023 at 23:34

I am so sorry, I just saw this…the last couple of months were really chaotic for me. Glad you enjoyed this interview.