Michelle Robinson is an award-winning animator and lens-based artist who received her Bachelor of Environmental Design in 1991 from Texas A&M University and completed graduate studies at Texas A&M’s program in Visualization. Robinson also completed her MFA in Visual Art at the New Hampshire Institute of Art in 2019. Publications featuring her personal work include The Hand, Diffusion of Light, One Twelve Publications, and Precog Magazine. Solo exhibition venues include the Dairy Center for the Arts (CO), Cecelia Coker Bell Gallery (SC), Yavapai College Art Gallery (AZ), Wright Gallery (TX), and Keystone Art Space Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Robinson has served as Character Look Development Supervisor for Disney on Ralph Breaks the Internet, as well as the Oscar-winning films, Frozen and Zootopia, and was Head of Characters on Encanto. She has also been a mentor in Disney’s Artist Development Program, taught computer lighting and texturing at the California Institute for the Arts, and served as a visiting instructor at Texas A&M University several times. She was nominated for a VES award for Animated Character on Wreck-It-Ralph and was named an Outstanding Alumni for the College of Architecture, Texas A&M University, in 2013.

I adore photography that crosses boundaries: mixed media, installation, projection; I love it all. I’m also a huge fan of work that is bound to processes. I find the methodical repetitiveness engaged by highly process-oriented works to add depth to projects. Perhaps that is the printmaker in me or just my love of Ann Hamilton’s installation works, but I’m not sure my why matters. It just is.

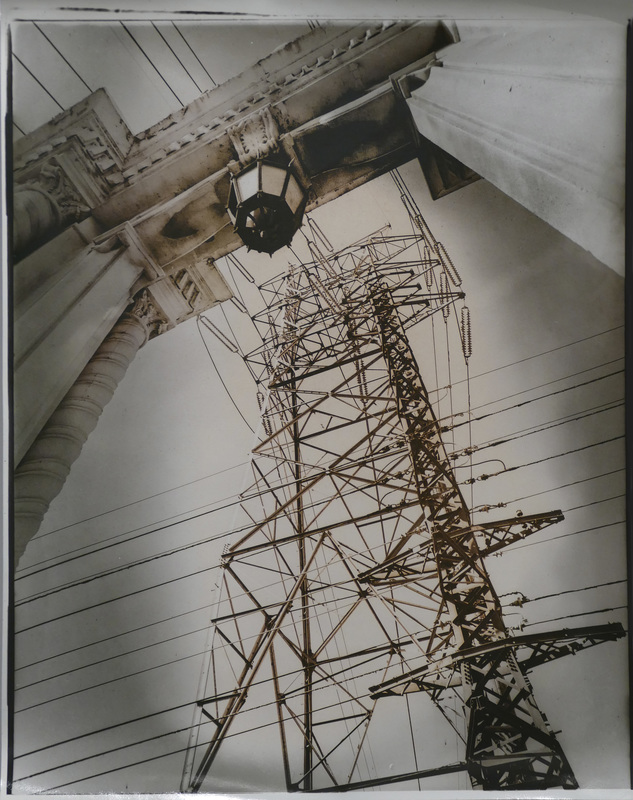

About a year ago, I stumbled upon Michelle Robinson’s work when I saw a PR notice in my FB feed from Kristine Shoemacher, an artist management specialist. It was for an exhibition of work entitled You Are Not Here by Michelle Robinson. After looking, I knew I needed to see more of Robinson’s work. I fired up Google, where I came upon a project she made called Transmission. Transmission was unusual in that it manifested in various forms, including wet darkroom work, collage, printmaking, encaustic, and sewing. Ultimately, I ended up writing about that series for One Twelve Projects.

I appreciate sublime work on fine paper because I love prints, and I LOVE paper; that love is deeply ingrained in the printmaker part of me. But sometimes, work is meant to be something more, something other, something different than a print to say what it needs to say.

Many people would have difficulty integrating such different styles into a cohesive project, but Robinson is so deft at this that she makes it look easy.

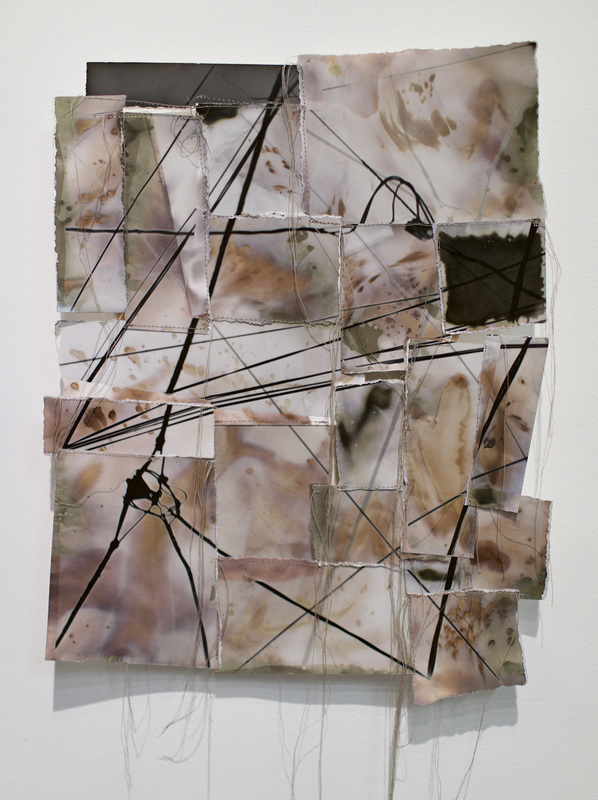

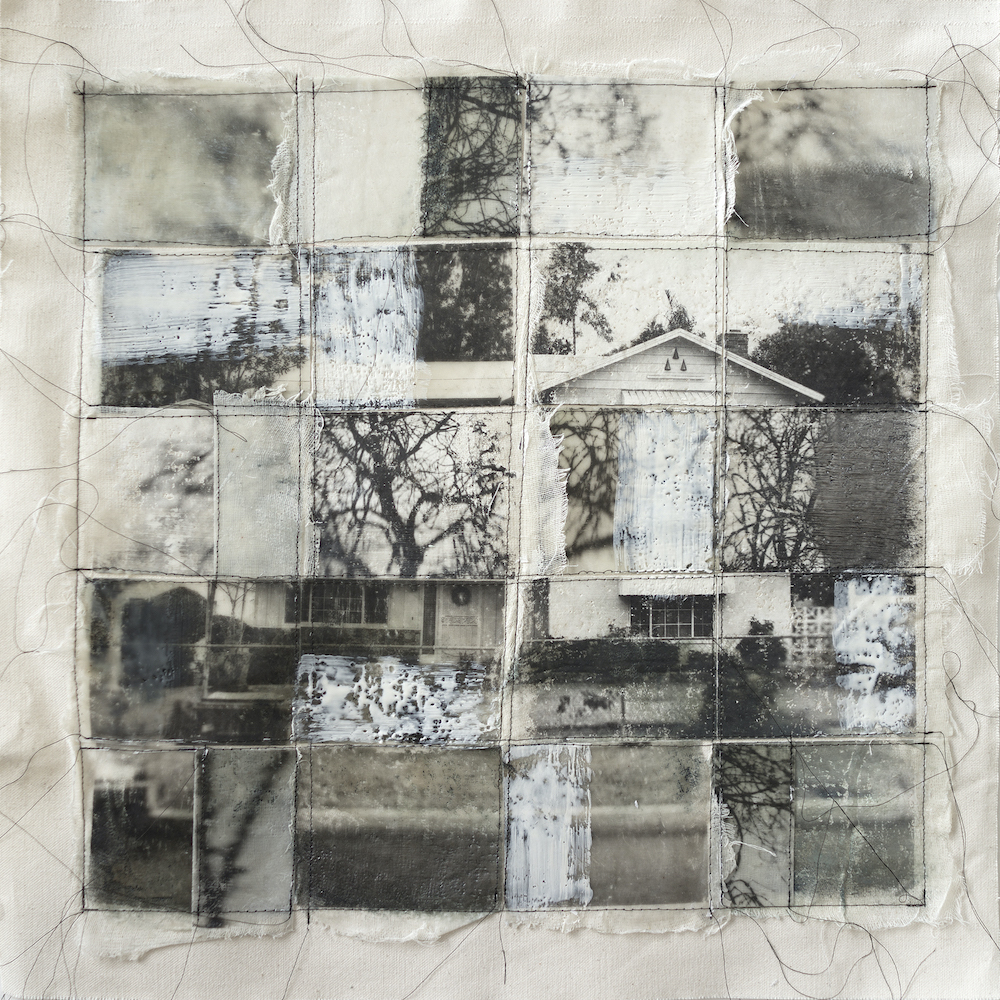

My favorites amongst the varied works are the most abstracted pieces. Processed by hand, then torn apart and sewn into new non-literal imagery, they are still evocative of nature and the built environment. The curled edges, irregular margins, hanging threads, and earth and sea tones all come together with the imagery to speak to an uneasy partnership between the manufactured and the natural worlds. That is not to say I feel the other works are poor stepchildren. It is simply that these works speak to my soul.

In the ensuing period, I have gotten to know Robinson over the net, and we are also both graduates of the Kipaipai Fellows Program (though not in the same session.) Yet, I was shocked by this interview. As I sat down to write, I was struck by the congruence of our thought processes about media having mana thereby imparting meaning when used well. And although our topics are quite different, we both approach our work with an underlying sense of melancholy and sadness, and both process life experiences via our art. Reading her responses to me, I felt much like the character in the song Killing Me Softly who wanders into a bar and hears a musician strumming her life. No wonder her work resonates so meaningfully for me!

Robinson maintains an active personal studio practice. Her current work is a mix of analog and digital approaches, producing physical pieces that examine the home and the domestic as an uncanny space.

Because of my love for Robinson’s work, I’ve asked her to spend some time here, filling us in on her life and work.

DNJ: Tell us a bit about your childhood – where you were raised and your upbringing.

MR: I was born at Williams Air Force Base in Arizona, where my father was a flight instructor and my mother, after a career working as a microbiologist for the CDC, was a full-time mother. My extended family is relatively small, and since we uprooted and moved every three years, we were a pretty tight family but perhaps a little insular. After Arizona, we lived in Ohio and then Virginia, where I developed severe asthma and allergies, with many trips to the emergency room and a lengthy hospital stay for pneumonia when I was 6. I have vivid memories of those experiences, which were often surreal and distorted due to exhaustion and medication. I remember lying in the back seat of our car on the way to the hospital and seeing the bare winter trees, lit up by streetlights, flashing by eerily, reaching toward me with seeming menace. I remember my room swimming before my eyes and the furniture appearing to melt due to a medication I took. Finally, my asthma was under control, but those experiences still surface in my work periodically.

I was a pensive, melancholy kid (perhaps due to those early medical experiences, but mostly I think it’s just my nature). I was acutely aware of the impermanence of things and the passing of time. I preferred sad songs in minor keys, and (it’s almost laughable now, given I was seven years old at the time) I remember becoming acutely aware that I was getting older and would never be the same age again. Nostalgia, longing, and a connection to the sadness of things have always been a part of me. These underscore my work.

We moved back to Arizona for my health, then later to Texas, but of all the places I lived, the landscapes of the southwest were the motherland, the landscape of my imagination and dreams. We always lived in the suburbs but often at the edge of natural woods or a park. Through walks in those wooded areas, my mother helped me identify flowers and birds, which helped develop my observational skills and my appreciation for science and the natural world. I also drew and painted as much as I could. There were no career artists in my family. Still, I grew up surrounded by my Grandmother’s palette knife paintings of the southwest, and I had the support and encouragement of my parents to pursue art as an interest.

DNJ: What brought you to photography?

MR: I was studying architecture as an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, and black and white darkroom photography was a required course for the program. Up to this point, if you had asked me what kind of artist I was, I would have identified as a painter; I’d studied oil painting for years and gotten reasonably adept at the medium. But I completely fell in love with photography during that course from the first moment I stepped into a darkroom. My first ‘real’ camera was a Pentax K1000, that nearly-indestructible workhorse of a student-grade machine. I had a fabulous instructor who knew how to help beginning artists find their voice. She was also the first person who taught me to think about art from a project standpoint rather than as an individual piece, where an idea leads to form in a thoughtful (and often serial) way. From there, I took every photography course available at the university, which fundamentally shifted how I thought about my work. I was continually delighted by the alchemical magic of the darkroom. I liked the immediacy of it, but I was not a purist. From the start, I wanted to push photography into places often occupied by more traditional media, incorporate some of the things I knew about painting into the work, and create unique objects that I couldn’t reproduce.

DNJ: When did you figure out art was your career path, and how did that happen?

MR: My family members were primarily scientists and educators, so as I grew up, I didn’t have any role models for that career path. I worried that it wasn’t realistically achievable. I think I also wanted stability; perhaps moving around as a child contributed to that. Initially, I chose architecture as a practical, pay-the-bills alternative. Halfway through the degree program (about the time I took that first photography class), I began to feel that I wouldn’t be happy designing buildings for the rest of my life and started looking for alternatives. A new graduate program called Visualization began at Texas A&M, focusing on computer animation, digital art, photography, and video. I entered the program in 1991, which was very early for this technology, but it seemed like the future, and I could see the potential for a stable career there. Remarkably, I was hired by Walt Disney Animation Studios right out of school. I got a job as one of a small team of 15 artists working on the CG elements in their 2D films, and I have been there for 29 years now. But even though animation is an artistic endeavor, it does not fulfill my inherent need to question, explore, and create. I have maintained my studio practice alongside my animation career for years and was finally able to complete a low residency MFA in visual art in 2019. While it is sometimes slow going depending on what my life demands, it is essential that I pursue my practice for my well-being.

DNJ: How much of your art practice is photography?

MR: I don’t necessarily identify as a photographer to others because that can set certain expectations. Still, much of my thinking and approach are grounded in the theory of photography. My definition of photography is pretty broad, so I would say most of my practice is photography. There is a photograph at the core of nearly everything I make, even if the outcome doesn’t resemble one. Much of my work considers the fragility of memory and its relative truth, the elusive meaning of home, and creating an archive. These seem particularly suited to the medium, too. Despite all we know about how people can manipulate photographic images, they carry a veil of authenticity that other mediums do not. We still believe in the I-was-thereness of a photograph, which can be very useful when talking about memory and loss.

DNJ: Tell me about the evolution of the different series you have done. What came first? How did each lead to the next?

MR: If I were to try and distill my practice down to the threads that resurface over and over through the years, it would come down to these: memory, loss, ruins, and the elusive meaning of home. For me, these are deeply interconnected, bound together by that overarching sense of melancholy and impermanence I mentioned earlier. The first serious project I worked on as an undergrad was a series of self-portraits made inside an abandoned, partially burned-out house that I slowly transformed and inhabited over a semester. After moving to LA, I made the Transmission series about the ruins of the LA river. My subsequent project was about how family secrets affect and corrupt memory.

As a visualization student, I made films about my memories of childhood illness; now, 30 years later, I am making work about the glitchiness of my memory as I age.

During the early days of COVID, I began a project about the isolation we experience in our suburban homes. I tend to leapfrog these ideas, one over the other, from project to project, and lately, I’ve been working on more than one series at a time; if I drop one thread for a while, I will pick another up where I left off.

DNJ: You work with many different media within the realm of photography. How do you determine what media is the right one for any given project?

MR: That is one of the fundamental questions in my practice! It’s a constant conversation with myself, as I have always been interested in the photograph as a unique object, with all the formal possibilities it implies. I get much pleasure from experimenting and trying new things; I constantly ask, “what if….” The danger is becoming enamored with a process or a material’s seductiveness to the project’s detriment. I tend to work on projects for a long time, so I can try several options and allow the form time to evolve as I go; I don’t necessarily get it right the first, second, or third time. Very rarely do I envision a completed piece in my mind and execute it.

I learned in graduate school to ask myself honestly what the media is adding to the content. How does it support the story I am trying to tell? I believe that materials carry content; a silver gelatin print brings an entirely different set of associations and inherent meaning than an archival pigment print, for example. Issues of scale are constantly on my mind. Shooting on film is a different experience than shooting digitally; it’s slower, more precious, and there is no immediate feedback. I think all of that has a presence in the work, so I make the process part of the equation.

Lately, I have asked what I can take away rather than add, which can be a painful exercise. What is the simplest gesture I can make that conveys the most apparent meaning? I used to be a bit of a maximalist but have slowly been paring back in recent years.

DNJ: Can you share your approach to creating the work?

MR: I am a processor, so I spend much time thinking, reading, and researching. Poetry, fiction, philosophy, and critical theory can all be part of the soup. I also look at and read about many other artists’ work. I don’t work intuitively, or at least not in the way people often mean when they say that. I think what we commonly call intuition is just our brain’s way of processing and synthesizing input and experience to solve a problem, so I try to feed mine as much as possible in the hopes that it will come up with something interesting. I take an almost scientific approach to my work; I start with a question, develop a hypothesis, test it thoroughly, and move on if the tests fail.

Once “Transmission” felt like it had run its course, I decided it was time to tackle a more personal subject. I’d been thinking about the weight of accumulated family secrets and domestic trauma and its impact on one’s memories and sense of place within the home. I found from my own experience that these can cause fracturing of self: an oscillation between states of longing and loss, coziness and dread, presence and absence. The quilt forms I had been working with seemed like a natural place to start exploring this idea, and I went back to some imagery of bare trees that referenced my childhood memories combined with photographs of small bungalows. I tore them apart and then sewed them together in a way that interwove my imagery, a literal representation of the fracturing I referenced. Unfortunately, they weren’t landing. They were too sentimental: sepia-toned, dreamy and nostalgic-looking, they did not sufficiently represent the feelings of loss and uncertainty I wanted to present.

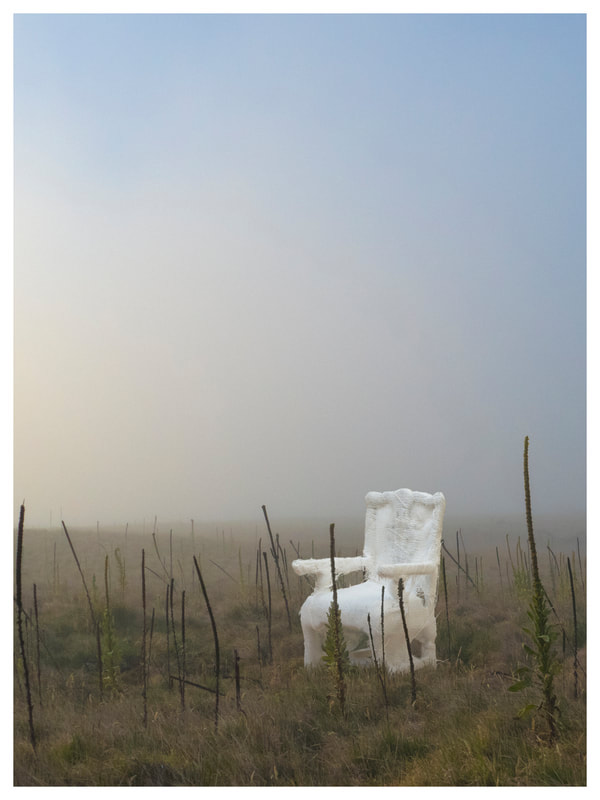

A mentor recommended that I read Susan Stewart’s “On Longing,” which crystallized the idea that nostalgia is a longing for something that never really was. That concept steered me away from the hand-crafted work I had been doing into something increasingly spare. Freud’s essay about the uncanny also figured heavily in this new project, eventually titled “You Are (Not) Here,” as a valuable way to think through the uncomfortable shift felt when secrets are revealed. I turned to Photoshop to play around with some ominous digital composites of suburban houses in unlikely landscapes. While I ultimately discarded those images, they were the catalyst for what I consider the project’s final form. “You Are (Not) Here” became a series of 30 digital composites of landscape and (un)homey objects. I chose to situate the project in desert landscapes (primarily Death Valley) because of that connection to my childhood and because the desert is a space of prolonged time. The objects function as proxies for people, characters in obscure narratives that play out in a harsh environment. They are dollhouse miniatures I built or altered by hand and photographed separately. Doing this allowed me to scale them up in the compositing process to near life-size without dealing with the depth of field issues and scale cues that would have tipped my hand if I had photographed the miniatures in situ. The play with scale was an intentional misdirect; I hoped that at first glance, the images might seem convincing, but after looking for a moment, they would break down into an uncomfortable uncanniness.

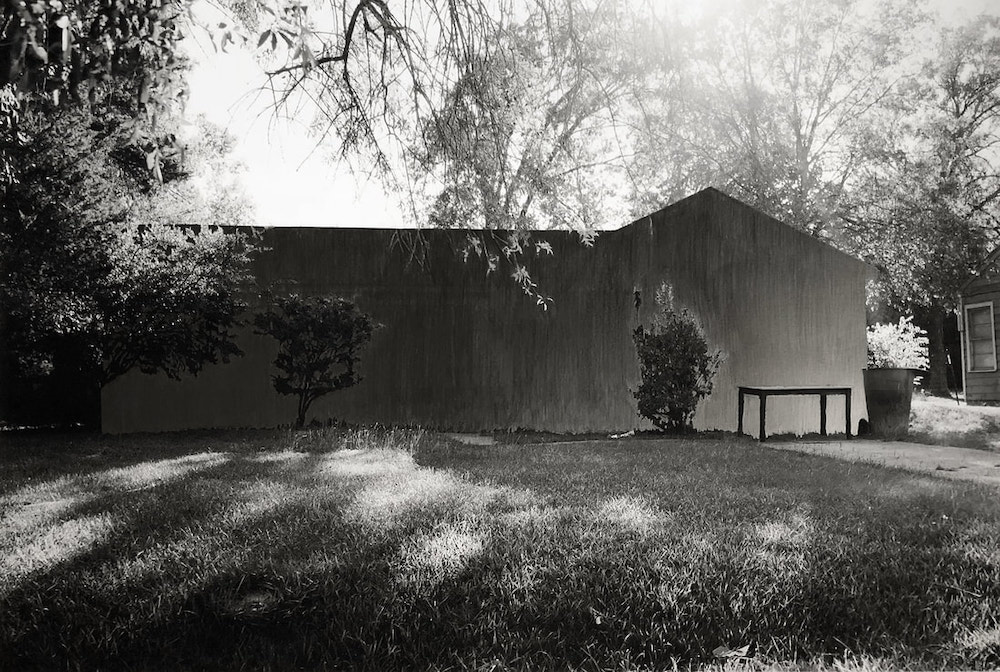

More recently, “Safer at Home” is a work in progress that started right before the pandemic but became more relevant as we began sheltering in place and my studio shrank to the size of a card table in my spare room. I had documented houses in neighborhoods that I had grown up in (or were similar) and, after having them printed, decided to redact the environment entirely by painting over it with matte gray-card-gray paint. I was thinking about what an isolating space a home can be. American suburbs were built on notions of personal space, safety, and an aspirational middle-class way of life. Yet, they have been historically exclusionary as well as illusionary. I continue to think about the secrets hidden behind the facades.)

DNJ: What message do you intend to send out into the world with the work you make?

MR: I process my life through art. I hope this doesn’t sound selfish, but for the most part, my work is mostly for me. I make work to understand something in the world or that has happened to me rather than to make a statement or persuade. Additionally, I use photography to draw attention to something I want people to see or consider. But I try not to be too prescriptive in that act of pointing. I want to leave space for others to enter the work their way. I often intentionally veil the narrative, always trying to find the right amount of personal story to include without positioning the viewer as a voyeur.

DNJ: What’s on the horizon for you?

MR: In October, I will head to a residency with Kipaipai workshops in partnership with the Joshua Tree Center for Photographic Arts. The intent is to do photographic work about the Joshua Tree to bring attention to its vulnerability in the face of climate change. I hope to collaborate with some scientists involved in their study and conservation. The trees have a complex life cycle; they take a long time to mature, require nurse plants to become established, and are fertilized via a particular moth species. They reproduce only a few times a century, and some areas have been described as ‘zombie forests’ because they are already, in effect, beyond recovery. This project will still be a substantial shift in the content of my work as I start to focus on this particular subject. And, unlike much of my practice, this may well be a project with a specific ecological message to impart. I’m excited to see what will happen!

I hope that you, my reader, have found Robinson’s fearless use of materials and exploration as fascinating as I do.

MICHELLE ROBINSON