Tokie Rome-Taylor is a 20+ year veteran educator and working artist who lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia. She was awarded her EdS and MAEd degrees from Lesley University. Previously she attended Morris Brown College, where she received a BA in Art Education with a concentration in photography and drawing. Her work has been exhibited internationally; venues include the Griffin Museum of Photography, the Marietta Cobb Museum of Art, the Masur Museum, and the Zuckerman Museum, among others. Her series, “Reclamation,” was honored by being named in the Critical Mass Top 50. Publications featuring Rome-Taylor’s work include Lenscratch, What Will You Remember, and Feature Shoot magazine. She has been a Funds for Teachers Fellowship recipient, which allowed her to study in Santa Fe and San Francisco. Rome-Taylor’s photographs are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia and the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, among other public and private collections.

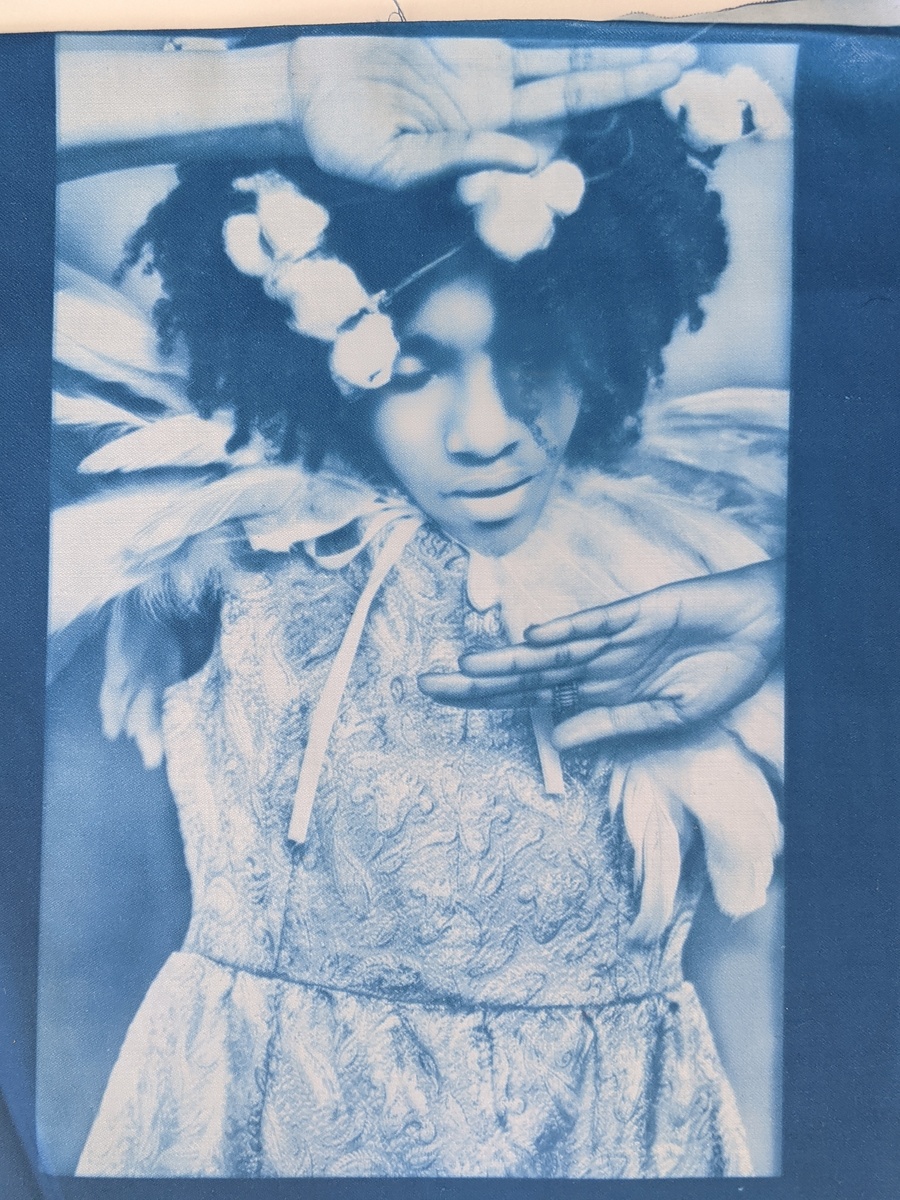

Tokie Rome-Taylor explores themes of time, spirituality, visibility, and identity via her photography. Primarily working with digital tools, she also uses alternative processes and alteration to explore the layered, complex relationship of the African American diaspora in America. Her techniques include cyanotype and intervention in the image via embroidery.

The issues Tokie Rome-Taylor addresses are not ones I have ever, nor will I, experience. Sure, my family name and some familial history were lost when an immigration agent changed my grandfather’s last name upon entry at Ellis Island. But that doesn’t compare to being stolen, sold, enslaved, and having family history, traditions, and cultural touchstones erased. The brutality towards and depersonalization of an entire race of people, and the generational effect of that, is something one can only know by having lived experience. No matter how empathetic we are to the experiences, we still are not directly touched by these issues unless we are members of that affected community. This leaves me feeling under-qualified to fully comment on the work because I can never truly understand the depth of the meaning it holds.

Although some of the individual symbol’s meaning may be out of my realm of experience, the images deliver a punch. Her images depict her sitters as proud and powerful, reclaiming their roots and heritage with honor. Personally, my response to the work is that it is powerful and profoundly moving. Due to my response to her imagery, I asked Rome-Taylor if she would be willing to share her thoughts about her artistic path and work with FRAMES readers.

DNJ: Please tell us about your childhood.

TR-T: I grew up in Atlanta, GA., in a family of twins. I have a twin sister who is an artist, too, and I have younger twin brothers. My mother, Yvonne, is not a twin, but my grandmother is. At last count, there were 14 sets of twins on the maternal side of the family.

In the South, things happen, but they are metaphorically ‘boxed up and tucked away in a corner.’ These things are never discussed, and they become secrets. My family is like that. People and history get cut off. We lose family history because conversations stop when trauma happens. Tenuous threads of lineage and the backstory of a family are severed all in the name of the southern traditions of “Pray on it, leave it with God, and it’s over now move on.” These Black southern traditions, which were carried out in my family, mean that much history gets lost.

My mom raised us by herself, with begrudging help from my grandmother. We moved a lot and depended on hand-me-downs and discarded items from others for clothing and toys. It was extremely rare for us to shop at a retail store selling new things when I was growing up. There were five of us in the family; for my mother to clothe and entertain four children 13 months apart in age, thrift stores were the norm. We were not overly sensitive to the fact that we were what most would classify as poor. The thrift store was a place of treasure hunts: books, clothing, toys. We didn’t have the latest fashions or trendy toys, but now, looking back, it taught us how to appreciate what we did have. I learned to treasure the items that others had deemed unworthy of keeping. The cast-off items of others became loved items in our household. This love of the discarded artifacts of others stayed with me as an adult and is a critical part of my artistic practice.

DNJ: What did you study in college? Was attending an HBCU critical to the path your imagery has taken? Or was it a choice you made as a senior in HS because you already knew the career path you wanted to take and felt it would help you achieve that? Do you think that attending an HBCU help shape the way you approach your work? If so, how?

TR-T: I attended Morris Brown College, a tiny, private, Historically Black College in Atlanta, GA. I studied Art Education with a focus on photography and drawing.

My college selection was to be based purely upon who would provide me with a full scholarship. My high school track coach, Randy Reed, was like a father to me. He encouraged my twin sister and me to attend college together. Morris Brown was his alma mater; he urged my sister and me to apply there.

I applied to PWIs (Predominantly White Institutions) and HBCUs and was accepted by all, three of whom offered me full scholarships. When Morris Brown awarded full scholarships to my sister and me, the matter was settled.

The Atlanta University Center, made up of Morris Brown, Spelman, Morehouse, and Clark Atlanta University, was unique in that you could take classes across all of the institutions. I had the pleasure of not only learning from instructors at MBC but across the various campuses. This flexibility exposed me to some of the best instructors within the South.

Graduate school can be a costly and unachievable undertaking for a first-generation college student like I was. I could not afford to stop teaching to work on an MFA or MA without the unique cohort program model that Lesley offered. Their instructors flew into Georgia to instruct students locally. At that time, they didn’t provide MFA’s as an option within that model, so I opted to gain a Master’s in Arts Integration and Curriculum, then, later on, a Master’s Specialist in Educational Technology. The programs allowed me to hone my skills as a teacher and artist while still allowing me to earn a living as a teacher.

DNJ: It must have been challenging to grow up in the South, with its celebration of often horrific legacies. In your interview with Aline Smithson at Lenscratch, you said, “I’m a daughter of the Diaspora and a child of the American South. I’m rooted in a place that has not taught its children any true history, beyond suffering, servitude and second-class citizenship. People of color, and particularly their children, do not see themselves mirrored or represented when they visit most cultural spaces. As a child I recall vividly not feeling any connection to the faces that peered back at me. They bore no resemblance to me. My work addresses a void in history and it is a void of ‘worth’ that was forced upon me.” Could you talk more about how that history impacted you and led you to this place where you actively work to address the lack of representation and cultural history?

TR-T: It was not difficult growing up in the South of my childhood, mainly because my mother kept us inside the house. It was her way of protecting us, keeping us away from things she could not control. (The Atlanta Child murders were happening during that time.) That, combined with the long hours my mother worked and her distrust of others caring for us, meant we were limited to only a few places outside our home. Our safe havens were libraries and the YMCA. We spent massive amounts of time at both.

The era in which I grew up was a time that certain people are trying to take us back to now, complete with their dog-whistles about CRT and the opposition to teaching a more truthful view of history – both good and bad.

We learned history from a Western-centric perspective. The United States and those that helped shape it, typically white males, were presented as infallible beings. All other subjects received the same treatment. Discussions of the Civil War centered on the North versus the South. The history was glossed over; Lincoln was hailed as a savior to Black folks for freeing the slaves. Blacks were enslaved people living in the Americas to harvest crops and act as servants to the white masters. Blacks were always presented as docile, ignorant subordinates to the white members of society. There was no discussion of their lives before slavery or how they arrived in the Americas. Native Americans received the same treatment. Settlers came to the Americas, and the Native Americans journeyed to another place the settlers could farm the land. The entirety of my education, both inside the school and within cultural community spaces, centered on a white perspective that also deliberately glossed over the facts of history in the name of teaching White Exceptionalism.

Our yearly school trips, a pilgrimage, would be to the Cyclorama. The 49-foot painting portrayed celebrated Union officers, while the portrayals of Confederate officers were not individualized. It was purchased and moved to Atlanta in 1891 by Paul Atkinson. He had attempted to recast the Battle of Atlanta as a Confederate victory by repainting a group of Confederate prisoners of war so that they became defeated Union soldiers. It was housed in the Civil War Museum, which displayed pictures and artifacts from that war. The Atlanta community had invested millions in memorializing and maintaining historical depictions and artifacts of a time when a faction of the country fought to maintain the enslavement of black people.

Trips to Atlanta’s foremost art institution, the High Museum, which reflected what was important within Southern society via the artworks it housed, yielded even more exposure to a Western narrative. This narrative completely omitted artists, artworks, or anyone that looked like me. These were the kind of cultural trips we took – to places that celebrated and elevated the narrow few while minimizing the narratives and importance of any culture that did not fit within the exceptional white narrative. I feel that such a limited perspective was deliberate, creating a sense of being lesser than within a society. The High has made tremendous strides since my childhood, but these are the memories that formed me.

DNJ: Why photograph children?

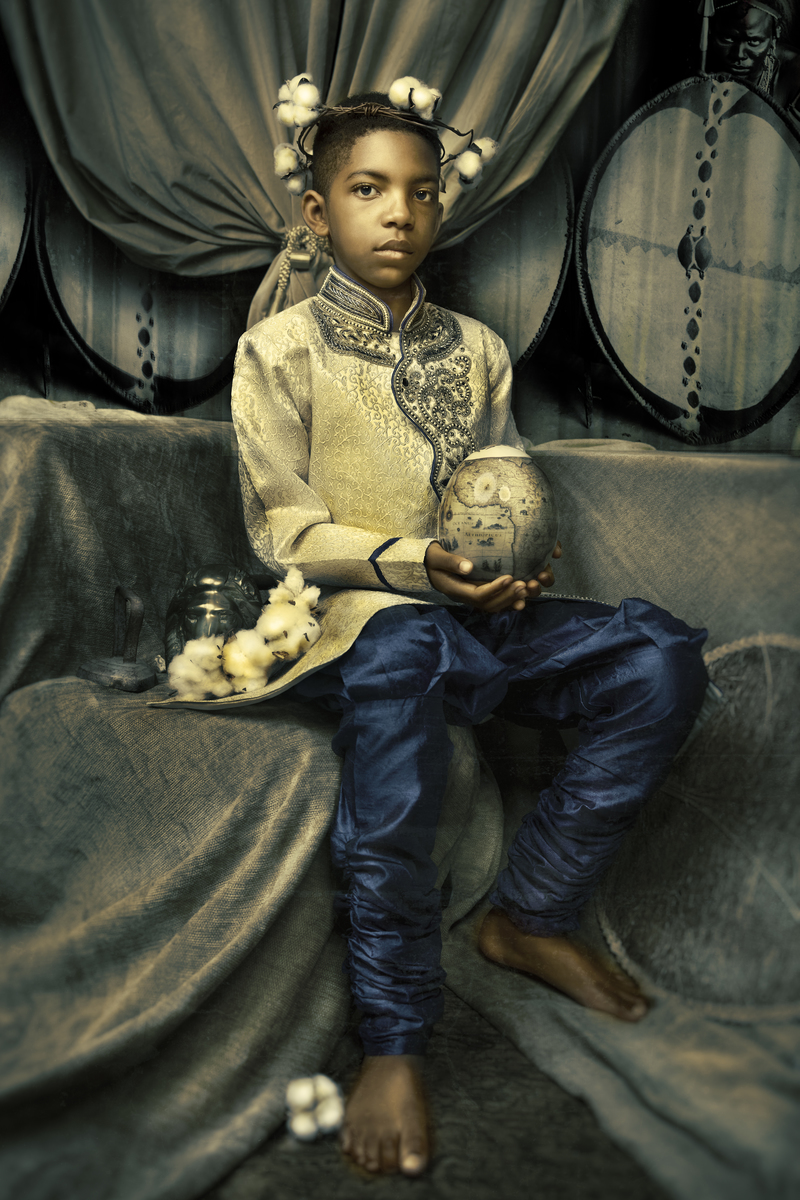

TR-T: Depictions of African Americans in traditional western art primarily centered on images of servitude, oppression, or archetypes that place African Americans in a submissive light. Those ideas have a psychological impact on how a person moves, thinks, and acts in society. Children of color have grown up with the historical narrative that their ancestors were subordinates, subjugated to all manner of horrors, and had to fight at every turn to be treated as human beings. Perception of self and belonging begins in childhood; hence children are the subject I use to speak of a sense of belonging.

My photographic images of Black and brown children re-examine the history and tradition I was taught. They are portraits that counter the inaccurate and stereotypical propaganda and the subjugated and inferior historical depiction of people of color. They represent a visual elevation that was omitted from mainstream Western history. My objective is that both children and adults view and imagine themselves and their history within these images. My work initiates conversations that explore heritage, rituals, and material artifacts which channel our history.

DNJ: Your work looking at the erasure of material, spiritual and familial cultural artifacts of people of the African Diaspora is profound and, in my opinion, powerful and essential. What sorts of research do you do when creating new images or series?

TR-T: Questions that stem from ethnographic and historical research that probe the material, spiritual, and familial culture of ancestral descents of southern slaves are entry points for me to build symbolic elements that communicate a visual language within my work. Books and articles on African Spirituality, religion, and material culture in the south, historical and familial narratives pulled from readings and my sitters are all research points. I take notes and build out the connecting threads of what I discover. These threads get translated into plans for artwork and the symbolic elements included in the pieces.

DNJ: How do you locate the objects with which the sitters in your photographs hold or interact?

TR-T: It’s a combination of pulling from items noted within my research, such as the use of buttons as power items, and identifying things that translate into a symbolic representation of what resonates with me within my research.

I believe objects hold memory; I integrate my family objects and the sitter’s family heirlooms into my image-making. I use them both symbolically and because the memories of those who have handled them before form an additional layer of history and meaning. In centering the sitter’s or my family’s heirlooms, the imagined and the actual histories of these children’s families collide.

DNJ: You are an incredibly prolific photographer. Could you speak of which works or series are personal favorites and why?

TR-T: That’s hard! I don’t actually have a personal favorite, but I will say that I can feel it when a piece is finished. There is a visceral sensation when it ‘hits.’ If I am working on something and it doesn’t tell me it’s done, I will walk away temporarily. I’ll work on another piece and come back to the former with fresh eyes. Or I’ll shift to my readings or try a different technique. Eventually, I find what that work needs, and it will come together as the finished piece.

DNJ: When did you know or what would need to happen to allow you to say that you “made it as an artist”? Mentally, I imagine that perhaps the Petrucci collection might be one touchstone.

TR-T: I have not ‘made it’ yet. For me, ‘making it’ means that the artwork I am creating exists in many major museums and art collections. Making it would be the work so embedded in the canon of Western art that an Art History book cannot be written without including my artistic perspective and artwork. It would mean art history would not treat art made by people of African descent as a subcategory outside of the standardized norm of the canon of Western Art History. I may never see that time. However, that is my goal.

I have taught for over 20 years, and I have seen the Art History books change slightly to include a broader narrative of artists. However, there is still a tremendous amount of room for perspectives beyond the old white male gaze. Ideally, I would like not to be forced to rely on Google in order to expose my students to a diverse range of artists.

DNJ: What’s coming up on the horizon for you?

TR-T: I’ll teach a painterly photography workshop at Penland School of Craft from June 5th to 15th.

Additionally, this summer, I have a solo exhibition with the Community Art Collective in Houston; it focuses on my cyanotype and encaustic work. I also will be in a group show at Falin Museum at the University of Virginia this coming Fall. It is my first time showing in Texas and Virginia; I am quite excited about these.

I am also nearly ready to send my self-published monograph, “Reclamation,” to be printed.

DNJ: Tell us about your book.

TR-T: “Reclamation” is a beautiful celebration of Black southern children as conduits of history and culture. It explores the notion that self-perception and understanding of history and belonging begin in childhood. Children need to see themselves depicted in a manner that celebrates them, their history, and their heritage. Without this visibility, a subconscious sense of not belonging within a society is created within an individual. My goal is to instill a connection to history and tradition in the children and adults taking part in this project and those viewing the completed book.

This project focuses on African American children of metro Atlanta as historical ancestors who have traded roles. I explore questions that stem from ethnographic and historical research of African Americans in the South. Material, spiritual, and familial culture of ancestral descents of southern slaves are entry points for me to build symbolic elements that communicate a visual language and exploration of history. In traditional western art, people of the African Diaspora were either omitted or were portrayed as objects of status and wealth for wealthy patrons who commissioned the works. The people were staged alongside objects that the commoners could never attain, showing how they were not valued as persons but as property. Such is the imagery and narrative that this project strives to address. I re-examine that history, creating images of an alternative past, where these children’s humanity, history, and worth as a people are seen and celebrated.

The book includes interviews of families discussing their family artifacts and history in the South, essays from art curators and writers, and my analysis focusing on the photographs’ connection to art history and the cultural traditions of African Americans of Georgia.

I feel Tokie Rome-Taylor doing is important work. We live in a specific era of American life and politics where hard-won civil rights that took years of effort at changing mindsets to accomplish are being impugned by highly placed officials who are determined to keep power rather than actually govern to better the life of all Americans. We should be far beyond this by this point in American history. For me, important is just a starting point description. It’s necessary work. I’m sorry that I need to write those words, but here we are.

I cheer Rome-Taylor, and many others who are doing work around the same and similar issues to please keep going. Make the voices known, make the lives known, make the white-washed histories known. Correct the false narrative.

I look forward to seeing her book and more of Tokie Rome-Taylor’s impressive work going forward. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me, Tokie.

TOKIE ROME-TAYLOR