Yukari Chikura (地蔵 ゆかり) was born in Tokyo, Japan. Her award-winning work has been exhibited globally. She is the winner of the 2016 Steidl Book Award; Steidl published Zaido in 2020 to great critical acclaim. Additional awards include the 2016 LensCulture Emerging Talent Award, finalist in the Lucie Photobook Prize, first place in the Julia Margaret Cameron Award and IPA International Photography Awards, and being selected by the Sony World Photography Award, the Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 in 2015-16, and FotoFest Discoveries of the Meeting Place. Residencies include an AIR at the Rokko International Photography Festival. Collections featuring her work include the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Griffin Museum, and the Bibliotheque Nationale de France. Publications featuring her work include the New York Times, the Guardian, the Financial Times, Vanity Fair, and Vice magazine.

Authors note: The artist is a native Japanese-language speaker with some light fluency in English. I am a native American English speaker who can say hello, goodbye, and thank you in Japanese. We conducted this interview with our native languages and the use of internet translation systems, and some back and forth negotiation of language and what we meant. Any errors induced in meaning by either of us are unintentional.

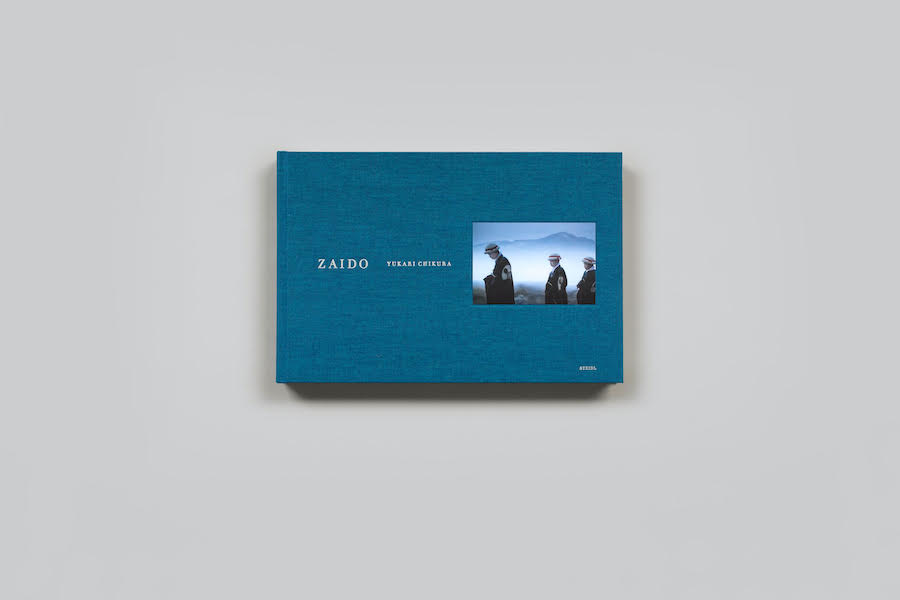

It seems to me that it would be near impossible to be an engaged photographer and not have heard of Yukari Chikura. Her recent book and project, Zaido, has received well-deserved international acclaim. Elizabeth Avedon, LensCulture, Vogue Italia, Photobook Journal, Photo-Eye, and a raft of other publications and blogs have named Zaido amongst their picks for “Best Photobook of 2020.”

I no longer recall how I “met” Yukari Chikura; we’ve been virtual acquaintances for around five years. Like many of us within virtual communities of photographers, we’ve celebrated our respective successes together via Facebook and Instagram. I’ve seen Zaido make ‘best of’ list after list and wondered from afar what the book might look like were I to hold one. Though I was familiar with some of the imagery, it was not until I started to write this feature that I found out exactly how well-conceived and executed this book was. Ultimately, how its design supports its concept is a thing of beauty. Its execution is so thoughtful that it is what I aspire to match if and when I publish a book of my own.

Chikura was raised in a quiet section of Tokyo. She lived mainly with foster parents rather than her biological parents, though she still spent time with her biological parents when possible. She has memories of her father singing opera and how much joy that brought her as a child. Chikura was a shy child; she spent time reading books and watching movies. She also played piano for as long as she can remember. As a child, Chikura was convinced she was not good at speaking with people. Although this may have hampered many other people, for Chikura, it became a way to explore different ways of communicating her internal self.

When it was time for college, she attended Musashino Academia Musicae, where she studied music, specifically piano. After graduation, she worked in the music industry, acting in composer and arranger roles. As a composer for television commercials, her clientele included well-known international entities such as Panasonic, Canon, Suzuki, and others. She also composed songs for Japanese Popstars.

DNJ: Do you feel that your music career influenced your photography work?

YC: To me, there is a lot of overlap between music production and the process of making visual art, and that music has a lot in common with photography. I experience the same feelings when I’m making music and taking photographs. There is a remarkable similarity in deciding which musical tonal qualities or image colors, and what emotions I want to express in either media.

Additionally, though the objectives were clear when working in music production, I constantly faced tight deadlines. In making required demo tapes, I had to do everything myself: songwriting, arranging, programming, and mixing. I developed ideas for what kind of worldview I wanted to express for each tune. That experience—the independence, the conceptual development processes, and meeting tight deadlines—helped when completing photo projects, especially in making photo books.

Though Chikura has not actively worked in the music field for over 15 years, she recently produced a soundscape for her 2022 exhibition at the Kyotographie Festival. (Kyotographie is an international photo festival held each spring in the ancient city of Kyoto, which shows collections and works by internationally renowned artists.) Chikura told me, “I had been away from music production and composition for so long that I felt as if I had forgotten everything! I really enjoyed the opportunity to learn about different and new techniques that had evolved in the time I had been away.”

Chikura also told me that she sees color and images when hearing sound and that sometimes she will think of music when viewing a landscape. I’m no doctor, but it sounds like Chikura may have the gift of synesthesia. Synesthesia, from the Greek’ union of the senses,’ is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive path will initiate a simultaneous involuntary experience in a second pathway, sometimes multiple pathways. These may occur in any combination of senses, but hearing and vision are the most common links. If you have synesthesia, you might also clearly perceive colors and shapes “in your mind” when you hear a tone or a melody. Why some people develop synesthesia remains somewhat enigmatic to researchers, but some experts believe this condition may be due to unique connections between different cerebral areas. Only 4-6% of the general population seems to have this perceptive ability. Still, scientists estimate artists are more likely candidates to have this sensory gift. (Note: After seeing my draft of this article, Chikura told me she was researching synesthesia and its possible connection to her life.)

DNJ: What brought you to photography?

YC: I started taking photographs to capture the faces of the people I met and to preserve images of the beautiful landscapes I encountered when I traveled, which I have always loved. It’s fascinating to experience the differences in cultures between my home and other people who live in the same era.

At first, I was just taking photos to document my travels, but then my experience traveling in Cambodia changed that. Cambodia was a place that left an indelible mark on my psyche.

It had been over 30 years post the Pol Pot genocides by the time I visited, but the evidence of that regime still scarred the country. I saw children who lost their limbs to landmines, impoverished children who could not afford traditional education sent to temples to be educated by monks, an ongoing HIV crisis due to inadequate medical facilities, and perhaps most heartbreaking, orphaned children wandering around rubbish heaps. Monks living at The Killing Fields had enormous piles of skulls of the massacred in their bedrooms. All this forced me to see how wars continue to plague people long after they have ended. That has greatly influenced how I think about life. At that point, I started to think more seriously about making photographs.

To ground the last part in a bit of context, I want to add some historical information. After the Cambodian civil war, the communist Khmer Rouge regime, led by Pol Pot, conducted state-sponsored torture and genocide. The Killing Fields comprise multiple sites where over one million people died. Pol Pot transformed Cambodia into a one-party state whose government forcibly relocated the urban population to the countryside to work on collective farms. His government abolished money, and all citizens had to wear the assigned identical black attire. Perceived opponents were dealt with by mass killings, and coupled with malnutrition and poor medical care, killed between 1.5 and 2 million people. Approximately one-quarter of Cambodia’s population died. Internationally denounced for his role in the Cambodian genocide, he’s regarded as a totalitarian dictator guilty of crimes against humanity. Some of you have likely seen the 1984 film The Killing Fields. It was based upon NY Times photojournalist Sydney Schanberg’s article, The Death and Life of Dith Pran. Filmsite.com summarizes itas “a remarkable and deeply affecting film based upon a true story of friendship, loyalty, the horrors of war and survival, while following the historical events surrounding the US evacuation from Vietnam in 1975. It detailed the atrocities of Pol Pot’s reign of terror in Cambodia in the 1970s. Cambodian doctor, non-actor Haing Ngor, in his film debut, was an actual survivor of the Cambodian holocaust, who was forced to leave the city and work in the labor camps of the communist Khmer Rouge. He was tortured and experienced the starvation and death of his real-life family during the actual historical events revisited in this film. He eventually escaped to Thailand and arrived in the US in 1980.” (Sadly, in 1996, Ngor was shot to death outside his apartment near Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles.) Reviewing this history while writing this article, I understand why visiting Cambodia would have profoundly impacted Chikura.

DNJ: You experienced a period full of profound loss and challenging life events coming fast upon one another. Did you find that photography helped you to deal with those? If so, how?

YC: The difficulties I experienced, including injuries from an accident and my father’s death, left me with constant fatigue. I found it hard to get out of bed. Only when I took photographs was I able to forget everything negative and immerse myself in the beauty of the moment and the pleasure of making pictures. It became a form of healing and a time of prayer.

DNJ: Do you always have a concept when you start a project or do you shoot and allow the images to tell you what the project that emerges will be?

YC: I’ve done projects both ways. Usually, I have a concept I’ve developed before starting to shoot. For all recent projects, that has been my practice.

All this leads me to Chikura’s best-known work, Zaido. In theory, the book is a documentation of a festival found while following instructions given to Chikura by her father in a dream; it is equally, if not more so, a love letter to her deceased father. The Zaido Festival is thought to be a solemn tribute to an ancient Shinto legend, the Danburi-choja (the ‘Dragonfly Millionaire.’)

Chikura’s point that she fears the old cultural touchstones may be lost seems to be apt here; I had to hunt deep into the web to find a reference to this story other than in an article about Chikura’s book. I found this information: “Danburi-choja concerns a poor farmer who fell asleep after tilling his fields. While asleep, he dreamt of a superior quality sake nearby. While he was dreaming, his wife had seen a dragonfly dipping its tail into his mouth several times. Near the rocks where the dragonfly had been they found a small stream that tasted like sake.” Not having a copy of Chikura’s book, I couldn’t say if this is the entire story. If it is, it is somewhat puzzling; I am probably missing specific cultural interpretation of the symbols. Because of my limited understanding, I am left to surmise that at some time in Japan’s past, having the right kind of sake was a means to or the raison d’être for wealth. (I’d bet a year’s salary that I’m missing the point.)

DNJ: You started with Zaido because your deceased father came in a dream and suggested you visit the village he once lived within. What made you decide that this dream held more meaning than typical dreams and was worth pursuing?

YC: A series of unfortunate events collided in a short time: the sudden death of my father, my serious injuries from several accidents, the2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, along with several other hardships, left me devastated in body and soul. Then, in that dream, my late father whispered to me, “Go to the village hidden in deep snow where I was a long time ago.” I felt an urgency in my father’s words. None of us know when we will die; it felt as if my father was trying to tell me that I must live each day to the fullest because tomorrow may not come. I thought that this dream might hold the answers I needed to really and truly live. It was as if some unseen force was leading me to the misty village.

DNJ: Tell me about the experience of making the photographs for Zaido.

YC: Japan is a country surrounded by the sea on all sides, contributing to our unique way of life and culture. Sadly, natural disasters are also part of everyday life here. I feared that some cultural traditions that have been maintained over the sacrifices of many centuries might be disappearing.

Ultimately, I followed the words of my late father, as said in that dream, and set off for the remote snowy mountain hamlet. Upon my arrival, I found the Zaido ceremony. The people in the village practiced this graceful and devotional dance ritual for 1300 years. People had to overcome many disasters and hardships to keep the flame of this practice alive. Due to their dedication to preserving it, it has survived all this time. What does it mean to overcome various obstacles over a long period to keep one’s culture and art for future generations? That was the idea behind my work entitled “Zaido”; I wanted people, including me, to think about that.

The people of the village had a lasting and profound influence on me. Because of their dedication throughout the centuries, despite wars, fires, thefts, and other hardships, I found the meaning of life again. It gave me the courage to move forward and live fully once again.

After returning to the area multiple times, I feel like I am returning home when I journey there. The people are very warm and friendly. Now, it’s as if they’re part of my family!

DNJ: What photographic techniques did you use to depict the villagers’ expressions and feelings as they performed each part of the Zaido ritual?

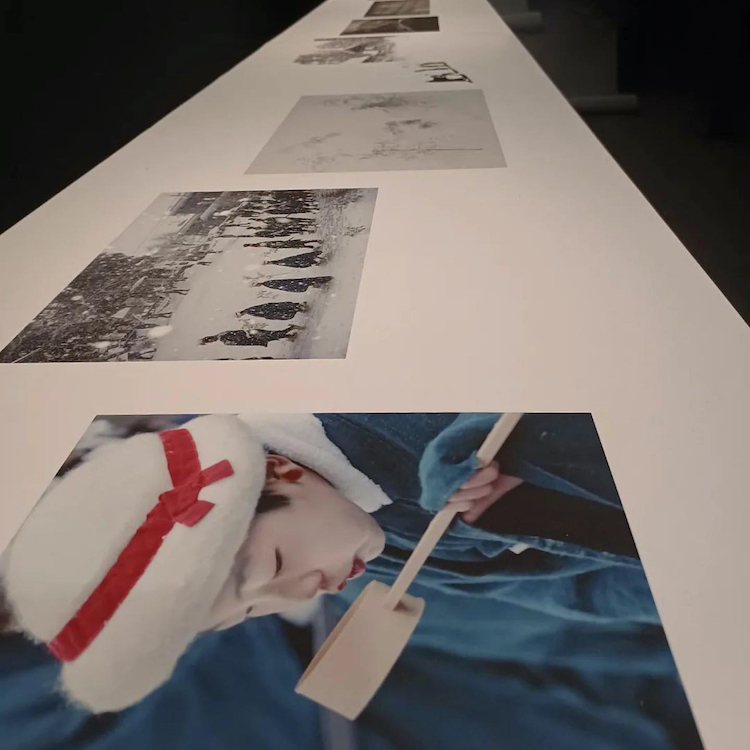

YC: I used strobes and slow shutter speeds to depict the past and other worlds. At the same time, I was challenging myself to create photographs that had a feeling similar to Japanese ink paintings.

DNJ: What challenges did you face in bringing Zaido and Fluorite Fantasia to fruition?

YC: Several things came up, each quite different.

First, it wasn’t easy to gain entrance to the community, which is small, tightly knit, and highly conservative. Also, the region’s unique dialect made it challenging to converse at the outset. It was pretty challenging to decipher the ancient documents I relied on for research.

Within the rituals I was documenting, specific areas are off-limits for women. I had to be careful not to breach those accidentally.

One of the devotional practices, mizugori, required that I shoot during a blizzard; I couldn’t see what was in front of me.

The dancers dedicate their dances in the mountains during the pre-dawn hours while it is still dark. I thought I was ahead of the crowd looking for an excellent spot to set up, but I got lost somewhere along the way.

I was luckily able to return by locating the sound of the flutes and drums.

Finally, when I was shooting, there were many bear attacks in that area. That made it nerve-racking being alone in the mountains taking pictures.

DNJ: Did you do the design alone, or did you have assistance from designers and editors? How did you secure funding for the book project? What things did you need to consider when working on the books?

YC: I funded the expenses for travel, shooting, and interviews myself. Photobook publishing is quite costly these days, so I was fortunate that the award fully financed the production process.

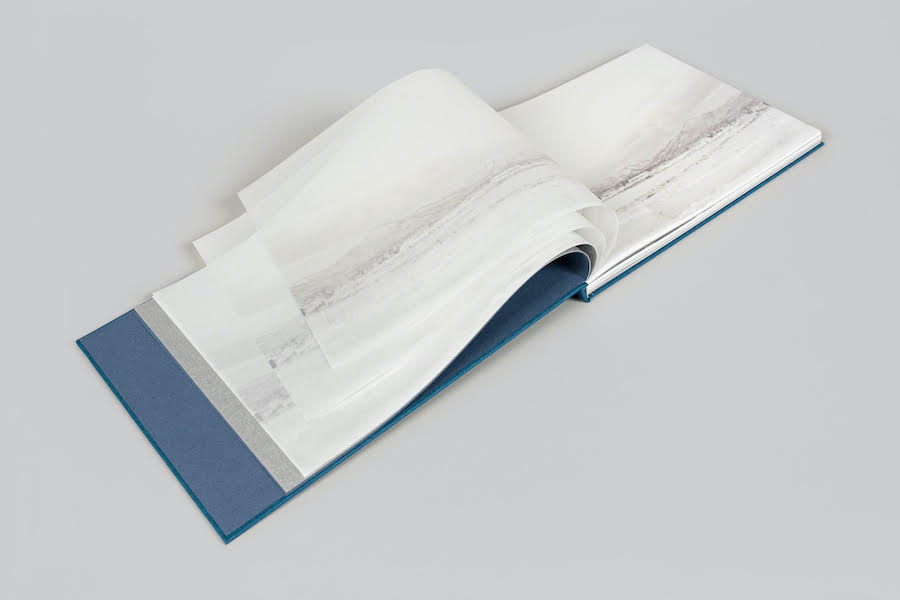

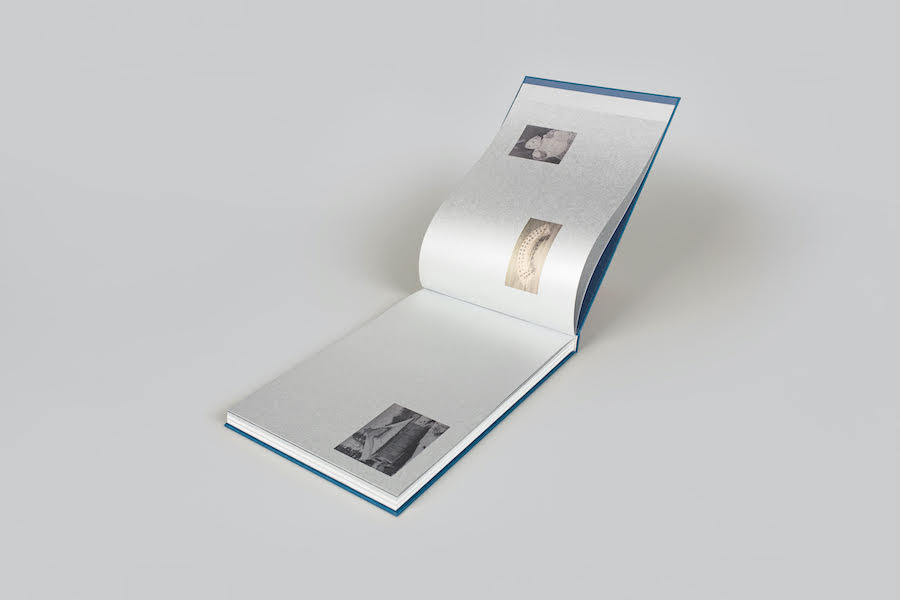

I thought about the book as if it was a symphony; that is how I wanted the reader to experience it. The materials selected, the different papers, and the different effects, were all done intentionally to give emphasis and meaning. My goal was to take the viewer on a journey into a mysterious world.

For example, when I arrived at the village, it was covered in fog. I used translucent papers at the beginning of the book to give the reader the experience of a gradual dissipation of fog. It also has a fade-out effect at the end, as if the snow were gradually disappearing into the darkness.

There are also ‘Easter eggs’ within the book; those are secrets and secrets and metaphors buried within the text and images.

The design and layout are faithful to my original ideas and enhanced by the publishing house’s work. Gerhard Steidl did many experiments with different inks and papers to solve the snow representations. Their designers helped me a lot with the fonts and the legendary annexes. I am grateful to them for considering all my intentions and creating a gorgeous, precious book.

DNJ: How long did it take to make the book version of Zaido?

YC: I was simultaneously working on both books, and I had only a short time before the deadline to submit them to the Steidl Book Award competition. I had already spent years taking photographs for “Zaido,” so I had many images to work with. I also had to translate the legends, make drawings, and things like that. My book dummy was bound using Japanese stab binding. I’d say that because of the deadline, I spent about two months in pre-production. The production of the original dummy version did not take much time, as mentioned above. Still, it took several months after receiving the award to complete the needed research to bring the book to its completion.

The award was granted in 2016, but the book was published in 2020. During the four years in between, I traveled to Steidl headquarters for four meetings. We made most of the decisions during our first meeting. I spent the second and third meetings with the designers working out the detailed layout, revising captions, and creating the separate “The Legend of the Danburi-Choja” book.

DNJ: Other than Zaido and Fluorite Fantasia, how do you decide what photo projects you work on?

YC: I am constantly researching and cataloging ideas for projects. I make lists of things that interest me, whether a book, a news story, or something I experienced when traveling.

DNJ: How does the exhibition version of Zaido differ from the book version?

JC: At the exhibition of “Zaido” at Kyotographie, several layers of prints are placed at the entrance, giving the effect of a Japanese Byoubu screen. But it also gives the appearance of a land mass with peaks and valleys.

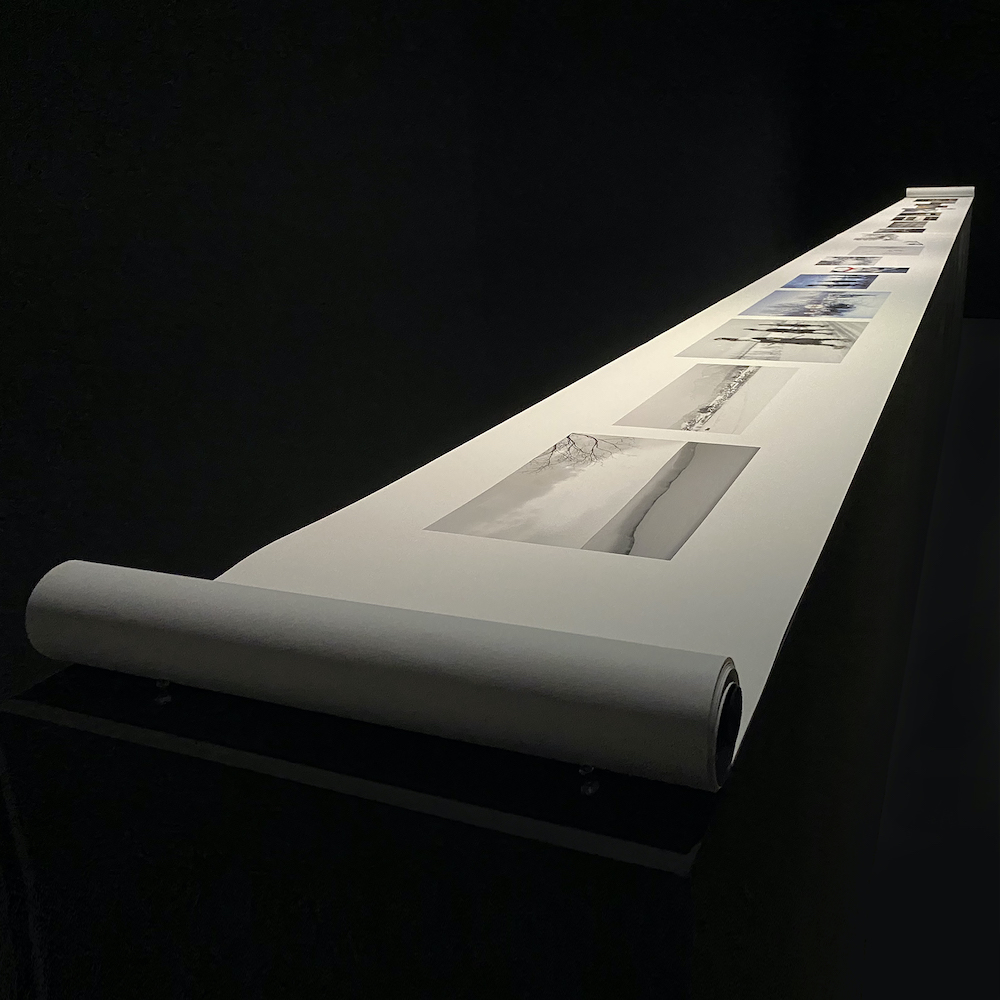

The snowy landscape images placed at the entrance to the exhibition are displayed in five separate pieces. If you stand in front of the photographs and look at them from a certain angle and height, each of the five disparate images appears as one continuous landscape. The presentation alludes to the ritual being seamlessly passed down from one generation to the next over its 1300-year history. In the center of the exhibition hall is a long scroll of pictures on a table. Usually, we view image scrolls from right to left, but these are meant to be viewed from left to right. The presentation also includes a soundtrack I composed derived from on-site recordings I made in the village. I presented it using directional speakers for added emphasis. The installation concludes with an image of an interminable staircase buried in snow. The picture is intentionally ambiguous; it causes the viewer to wonder which direction to travel, up or down? The entire exhibition is enigmatically designed to push the viewer to ask questions—past or future? This world, or another one?

DNJ: What is next on the horizon for you?

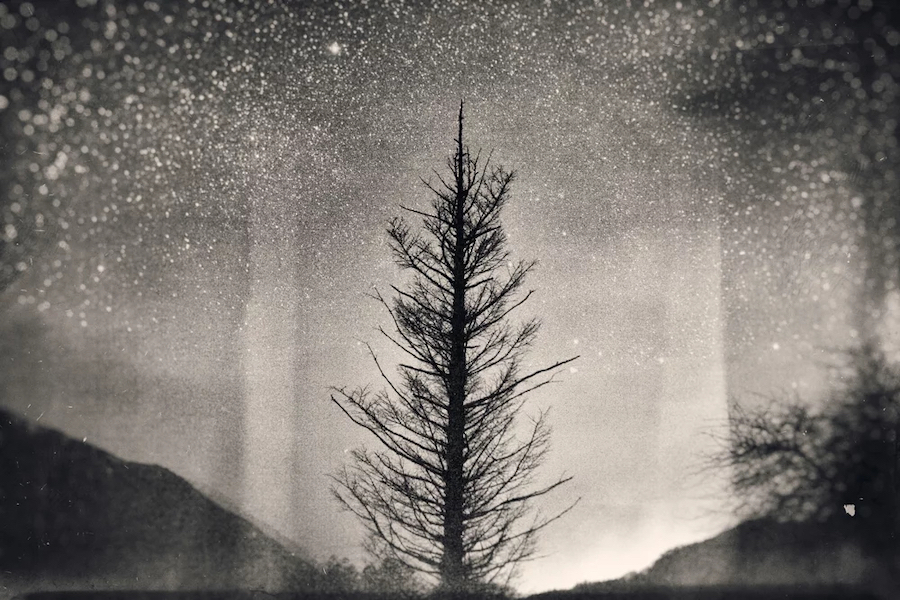

YC: I am currently working on several ongoing projects. One of them is a

different direction than my usual work. I started it in 2014 and have been

slowly making images for it. It’s about climate change, about human impact

on the environment. It’s called “Aschenacht, Schneemorgen (Ashen Night,

Snowy Morning).” I am also continuing my work with “Frozen World” and

“Flurorite Fantasia.”

Thank you so much, Yukari-san, for your touching and thoughtful responses to my questions and for sharing your story with FRAMES’ readers. I look forward to meeting you face to face at some point and to seeing your forthcoming projects.

YUKARI CHIKURA

Titima

June 25, 2022 at 23:40

Really love the article. The story is so beautiful and inspiring. Thanks so much Diana.

Diana Nicholette Jeon

July 1, 2022 at 00:28

Thank you ever so much, Titima, for the kind words and for reading. It makes me really happy when people respond to the artists I interview. Thank you again.