When we talk about photography, we often get trapped into talking about the images. The composition, the use of light, the nuances of evocation in portraiture or the gravitas of landscape. What we don’t talk about nearly enough are the ideas and issues that surround photography. Aesthetics and technical matters are all essential and very fine. But what about ethics? What about social responsibility? What about the physical safety of the photographer and the need to document difficult situations?

“Through The Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter” by Lauren Walsh

Published by Routledge, 2022

review by W. Scott Olsen

There have been profound critics and philosophers about photography in the past, and recently the voice I find most interesting is that of Lauren Walsh. Walsh teaches at The New School and New York University where she is the Director of the Gallatin School’s Photojournalism Lab. She is also the Director of Lost Rolls America: a national public archive of photography and memory. Walsh has a particular talent of bringing voices of photographers together in conversation, to help us understand not aperture or the rule of thirds, but significantly more important things like dignity and context and purpose.

Her new book, Through The Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter, is a book of morals and beliefs and values that form the core of who we are, our work and why we do it.

Walsh is the author/editor of a book a few years ago called Conversations on Conflict Photography (Bloomsbury Visual Arts 2019, then Routledge 2020). In that book she interviewed a number of photographers as well as editors and organizations to try and wrap our heads around what it means to photograph in a war zone. Structurally, the new book is a follow up to that one. Yet, Through the Lens can and should stand entirely on its own.

Through The Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter is a necessary book for anyone who picks up a camera and tries to document contemporary life. It takes as its premise the year 2020. 2020 was the year of Black Lives Matter and, shortly after the new year, the January 6th insurrection at the US capitol. As she says in the introduction, “The purpose of Through The Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter is to take a deeper look at the months prior to January 6, examining the multilayered conflicts that profoundly marked 2020, and especially to consider the intricacies of documenting and distributing the news with a camera.”

2020 was profoundly complicated and so there is no easy or single response from the photographic community. The genius of this book, like the earlier one, is that it’s organized as a series of interviews. What we get is a collection of points of view in in succeeding chapters. And the result, happily, is that the whole is much more than the sum of the parts. There are difficult issues here. For example, how do you photograph a pandemic when a patient’s right to privacy is also a solid moral position? When New York City has refrigerated trucks acting as temporary morgues, is it necessary to photograph that image to convey the depth of the situation? Is that an invasion of privacy? Is it sensationalism? And what about the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd? Certainly the protests were in public space, a perfectly legal environment for photojournalists to work in. But if facial recognition technology can be used on an image to identify the protesters to the police, what are the ramifications of that ability? Does the ethnicity and gender of the photographer matter when covering racial protests? Does the photographer really need to become embedded in a hospital to document the dying of COVID patients?

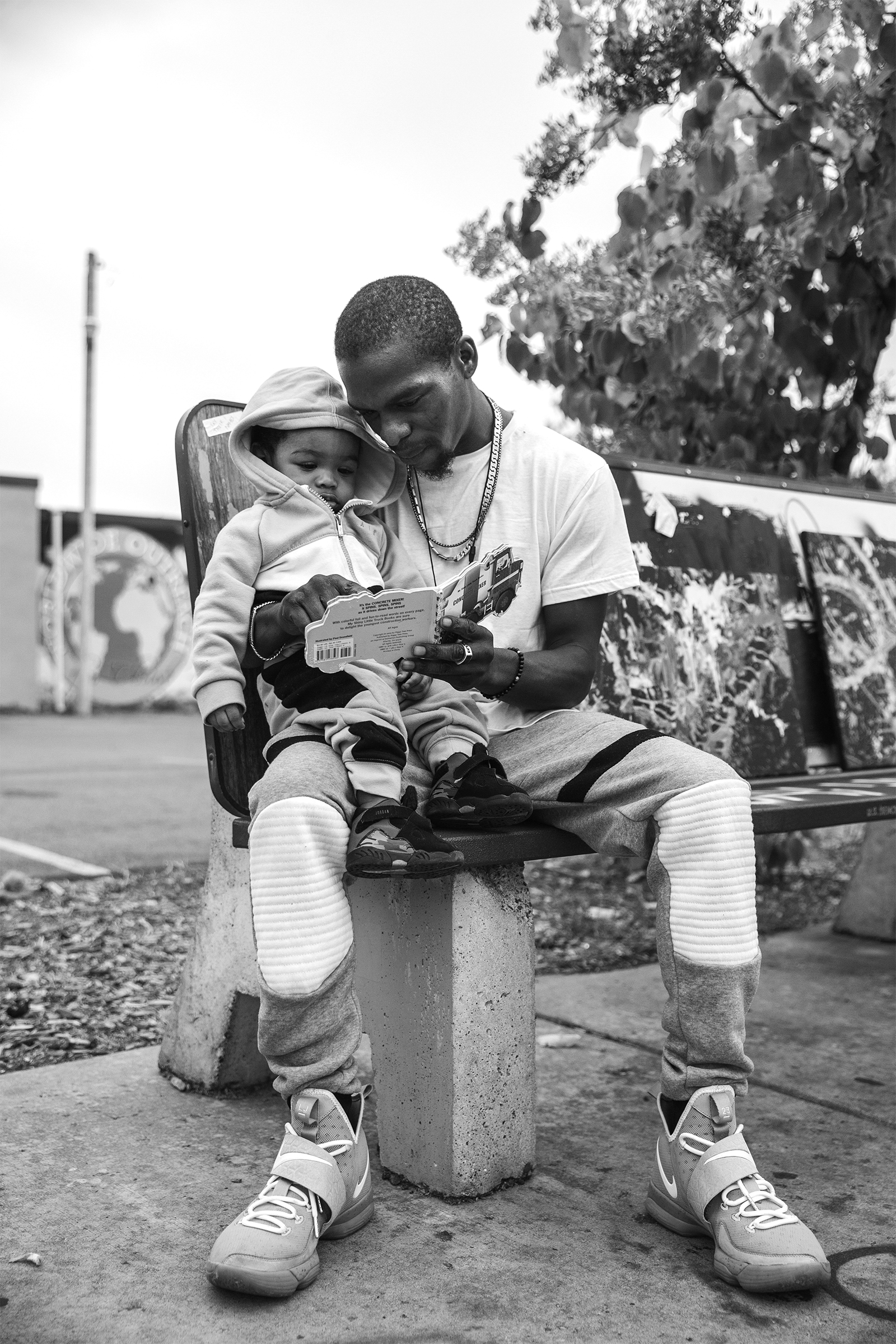

This book approaches, from a variety of perspectives and backgrounds, issues that inform our understanding of the photographic record as well as process. For example, award-winning photographer Nina Berman explains, “We [the photo journalistic community] are rethinking the idea of whose pictures tell the story, and paying more attention to who is behind the camera and what that person’s lived experience, as opposed to only their photographic ability, brings to the story. This is a big change in the industry and a welcome one. People see differently depending on who they are, the circumstances in which they were raised, their privilege or lack thereof, their class origins, race, gender identity, cultural influences, and on and on. And so if we’re going to try to document the world in any kind of meaningful and insightful way, then a diversity of witnesses and creators is essential. What’s surprising, when you think of it, is how long it took to get to that moment.”

Freelance photographer Patience Zalanga says, “I can’t separate my Blackness from my work, and my Blackness informs how I see the world. It informs how I document moments, and the same should be said about white people who are also within this field. Your whiteness does inform how you see things, how you report the news, what you choose to document. We are all subjective.”

This is followed by Danese Kenon, Director of Video and Photography at the Philadelphia Inquirer, who says, “If we are talking about allowing subjectivities or biases into the work, then we are no longer talking about journalism. As for captions, they should be neutral, giving the details of what happened, of what we see in the image. There should be no commentary. In terms of the visuals, we need to cover all sides of any situation. No matter, say, who you voted for or what you believe, you need to be over able to cover fairly. You can’t be an activist in your work. I just want you to be able to tell the truth with your camera.”

These are not contradictory comments. They are, instead, the details of the complications. Each of the interviews in this book are detailed and nuanced, solid attempts at getting at least he questions right.

Director of Photography at the Washington Post, MaryAnne Golan says, “This is significant because it informs the photography we see. There is a white male gaze. As there is a female gaze, and a person of color gaze, and so forth. What I mean is that obviously the person behind the camera is deciding what to show you and what to photograph and how to photograph it. So the critical question is: is what the photographer sees truly representative of what’s out there? And ever more, the next question is: are the people who are chosen by the photo editor to take the pictures members of the community that is being documented, or are they parachuting in? Getting back to the racial injustice, in order to change the current situation, there needs to be more understanding of the underlying issues. I don’t know if photography can be a tool to correct racial injustices in this country, but it can be a tool to expose them. It can be a tool to explain. And no matter who’s holding the camera, the underlying ethics of photojournalism should be the same. Every photographer should approach everything that they cover with an open mind and an empathetic perspective.”

Issues in this book are articulated by photographers as well as editors. Editors worry about PPE when sending photographers into COVID zones. They worry about body armor in protests. At least in these interviews, the editors all seem to have the well-being of their photographers in the forefront of their thinking. And there is the drive, not only for the dynamic front page but for the integrity of reporting on difficult situations.

For example, Walsh asks Danese Kenon, “Now, coming up toward a year after the shutdown, is the public fatigued by this coverage? If so, does that influence your photographers work?”

Kenon replies, “The public is definitely experiencing COVID fatigue. I think it hit around September or October. But that doesn’t change how our photographs photographers operate. They are charged with documenting what is out there and not with varying their imagery or their coverage to suit the mood of the public. So it makes no difference to us, in terms of coverage, that the public is fatigued. Where it does make a difference is that we see people relaxing their behaviors when it comes to the safety precautions, and that can put the photographers at risk.”

Through The Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter is a book for thinking about photography. Yes, it includes a great many provocative and profound images. But for every photographer who has ever wondered about the limits of a frame, every photographer who’s ever worried that they’ve missed something or that their own opinions and backgrounds are insidiously determining something that might be unfair, this is one of the essential books. The voices of the photographers in here are eloquent. The conversations with editors are illuminating. Reading this book does not address field composition or evocative use of shadows. But this book will make all of us more thoughtful and informed. A priori, to be thoughtful and informed is just as necessary when holding a camera as anything else.

LAUREN WALSH

WEBSITE

“THROUGH THE LENS” BOOK ON AMAZON

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.