It is relatively commonplace for a collection of photographs to have an historical intent. We are accustomed to looking at old photographs, especially of places we know well in our present time, and marveling about the change between then and now. Photographs preserve not only the façade of the past, they give substantial evidence of the tone and character and ethos of our world before any one of us took breath.

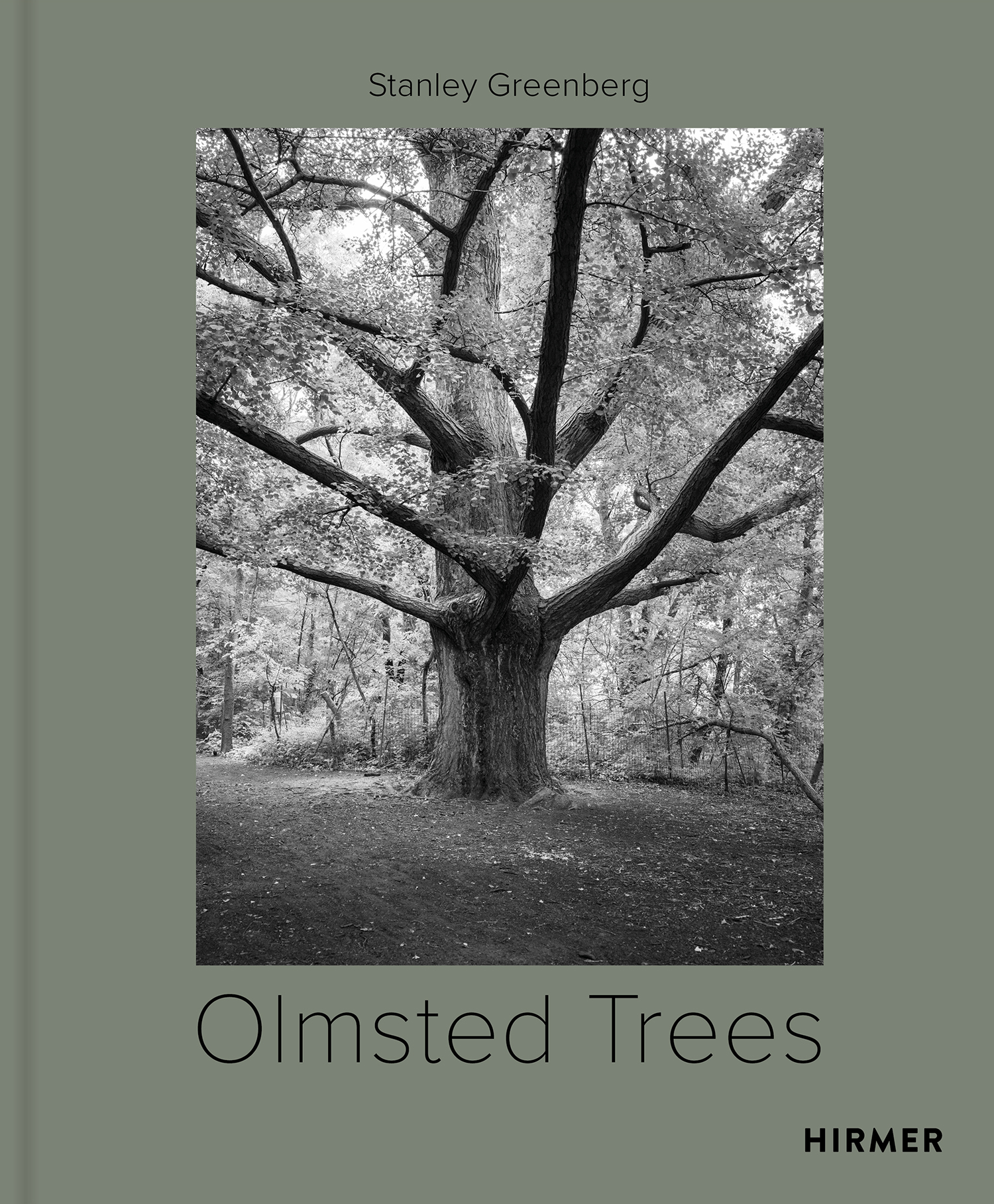

“Olmsted Trees” by Stanley Greenberg

Published by Hirmer Publishing, 2022

review by W. Scott Olsen

Sometimes, though, this historical intent gets stood on its head and the results are fascinating.

Olmsted Trees is a contemporary collection of black and white photographs of trees, old trees, mostly centered on the base of the trees’ trunks. The trunks are gnarled and twisted and shaped by time. They are intensely detailed and textured and give evidence of more than a century’s growth.

(across from Boat House. present in 1903 Prospect Park)

© Stanley Greenberg

And that is exactly the point. The story of these trees, and the reason they are so intriguing now, begins more than a century ago.

Frederick Law Olmsted (Wait, you’re thinking, I know that name!) was a landscape architect, among many other things, in the 19th Century. He was responsible for New York City’s Central Park as well as Prospect Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace and Franklin Park, Washington Park and Jackson Park in Chicago, and the US Capitol grounds in Washington, DC. And Olmsted had a genius approach to his thinking about the use of his designs over time.

Olmsted Trees contains three insightful essays that help place the project in historical, aesthetic and personal contexts. In “Rooted In Place” by novelist, historian and journalist Kevin Baker, he writes,

…Olmsted always embraced the idea that his parks were to be used, and to change as they were used.

“[We] determined to think of no results to be realized in less than 40 years,” he later wrote to his son and protege Frederick Jr. “I have all my life been considering distant effects and always sacrificing immediate success and applause to that of the future.”

Vital to these “distant effects” were Olmsted’s trees which he loved. Nothing else would “improve” so dramatically or so gracefully over time.

You can see the approach. Olmsted planted trees in what would become the most important, well-known, most used urban parks in the United States. He knew, or at least hoped, they would grow and develop and change the – what, wisdom? – of the parks over time. More than a century and a half later, Greenberg brings evidence that Olmsted’s hopes were well-founded.

© Stanley Greenberg

In “Orange Park and the Making of an Attachment,” social psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health Mindy Thompson Fullilove writes,

This dynamic world of wildlife, moving water, people seeking to connect, and trees standing sentinel is nestled in my heart, yes, but that is a wholly inadequate way to describe the whole-body connection I have with the park and its pond. My feet remember the ice when it was smooth and when it was pockmarked or bumpy My eyes remember the kaleidoscope of colors as the leaves turned and their colors were intensified by their reflections in the water. My ears remember the sound of a stone falling into the water, causing ripples, and my hand remembers the feel of the stones that I liked to cast.

This is what place attachment is about: that our minds and bodies fill with interactions in a place, interactions with whatever or whoever is there, from ducks to oak trees. We integrate a long succession of place stories and body memories as we go from place to place, as our circle of life broadens throughout the years.

Tom Avermaete, a professor of History and Theory of Urban Design at ETH Zurich, writes the book’s concluding essay. He takes an historical as well as political/aesthetic approach. He writes,

Olmsted’s designs for New York and Boston are, however, more than just a demonstration of how nature can complement and improve the urban environment. They represented the start of a social and political movement, known as the Parks Movement, which changed the course of urban design in North America and beyond. For Olmsted, modern urban planning was a democratic process in which people should participate. In his view, parks offered a great opportunity to raise awareness with all citizens about their collective responsibility to take care of the resources, green and otherwise, of the city.

Based on this view, Olmsted designed parks that explicitly provided equal access to nature.

© Stanley Greenberg

The images in Olmsted Trees mostly take the same approach to composition. We get the base of a trunk and some lower branches, centered in the frame. The images are black and white, taken on fair weather days without dramatic lighting. This is documentary work much more than fine art, and the result is a viewer’s eye is drawn to the intimate and idiosyncratic details of each tree. The trees are particular and individual. Each image has a caption that makes a tree exact. For example, “Ulmus minor, English Elm – Central Park, New York, New York, 2021.”

© Stanley Greenberg

Olmsted Trees is a deeply engaging book. Greenberg’s images are sharp and seem to revel in the ability to show the nuances of a tree’s bark and shape, and thus the implied history of weather and growth. Instead of looking at some artifact of the past, as it was a very long time ago, and wondering about time starting then and moving toward now, Olmsted trees shows us something today and tells us the origin story – so we wonder about time starting now and moving backwards toward the reason for its planting. Every image reveals a history and a desire.

Published by the German press Hirmer Verlag, the book’s text is offered in both German and English. It also includes a compiled list of Olmsted parks represented in the book with key dates and a map.

According to the book’s press materials, Stanley Greenberg is the author of several books, including Invisible New York, Waterworks, and CODEX New York. His photographs are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and The New York Public Library, among others. He has had one-person exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago and the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Greenberg has received fellowships and grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York Foundation for the Arts.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.

Susan Gans

February 9, 2023 at 18:42

Excellent review of this interesting book. Ordering it. Wondering if I have stood against an Olmstead tree in Central Park or on the Mall in Washington, D. C. An adventure will be planned. The photographs present the trees with all their majesty. Love the parks and Olmstead’s attitude in planning them.

David Gene Lang

March 9, 2023 at 16:09

Maybe thats where we meet in NYC!

Paul Genin

February 10, 2023 at 06:23

Quite lovely. And is an inspiration to again work with film, chemistry, and paper.

James Harrison

February 23, 2023 at 12:33

Informative article.

David Gene Lang

March 9, 2023 at 16:08

An interesting perspective of the life the trees have seen in the Olmstead parks. I’ve been an admirer od Olmstead for awhile. As quoted above his vision was for parks for all classes of people, because he reconized many citizens lived in cramped crouded buildings with little space in which to enjoy nature. He is an icon here in Hartford, CT where he was born and is buried.