Sometimes, to read a book, you have to shut the door. Not because of secrecy or a need to hide, but because you want to close out the distractions. This book is important. This book opens a story that’s soul-honest and private and you realize, quickly, this one deserves not only your attention but your respect.

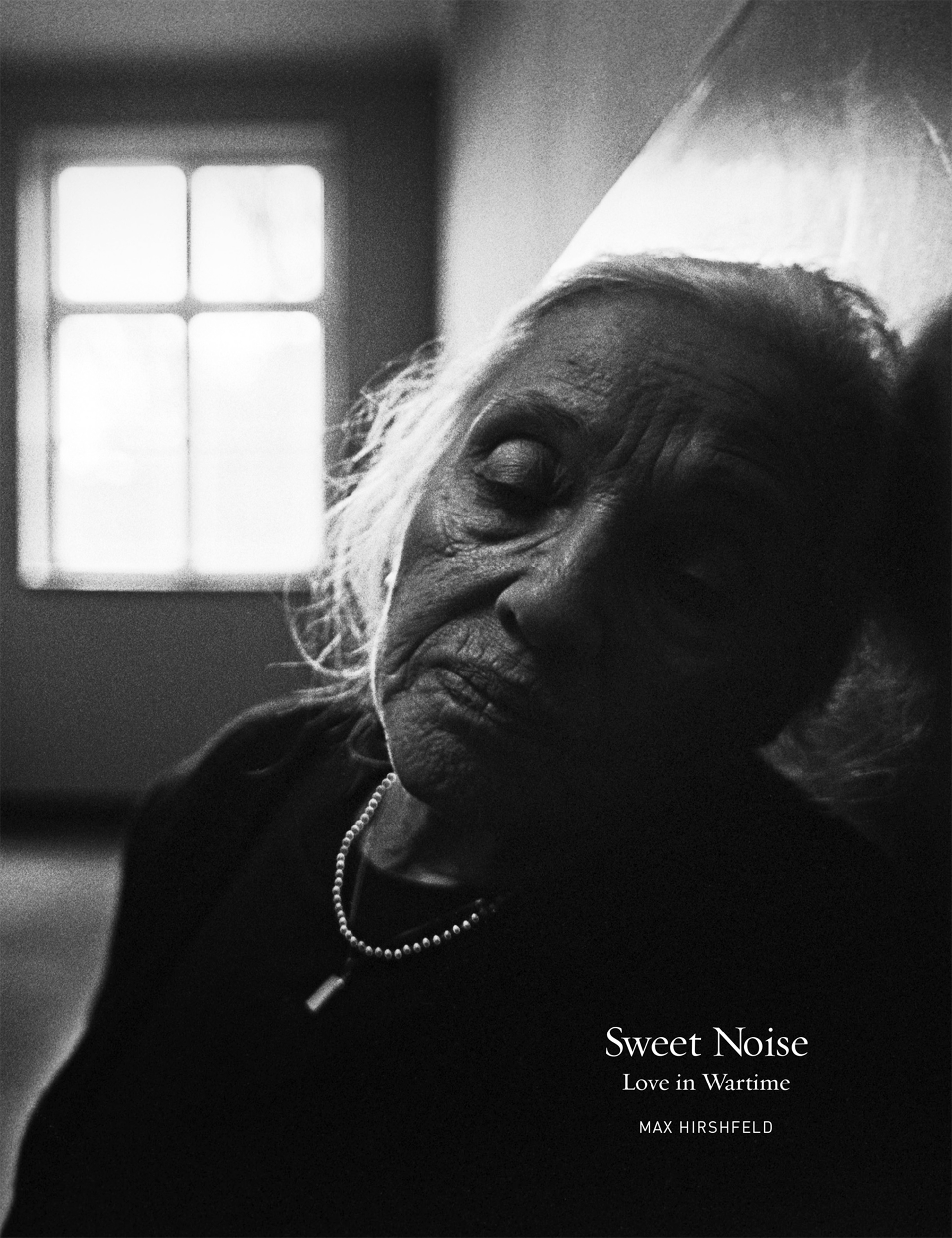

“Sweet Noise: Love in Wartime”, by Max Hirshfeld

Published by Damiani, 2020

review by W. Scott Olsen

Sweet Noise: Love in Wartime, by Max Hirshfeld, is one of those books. Hirshfeld’s parents were Holocaust survivors, and at one level the book about their lives after the war, how first one and then the other came to the United States, and how Hirshfeld, growing up, came to learn and understand their story. But reducing the book this way is already doing it a disservice.

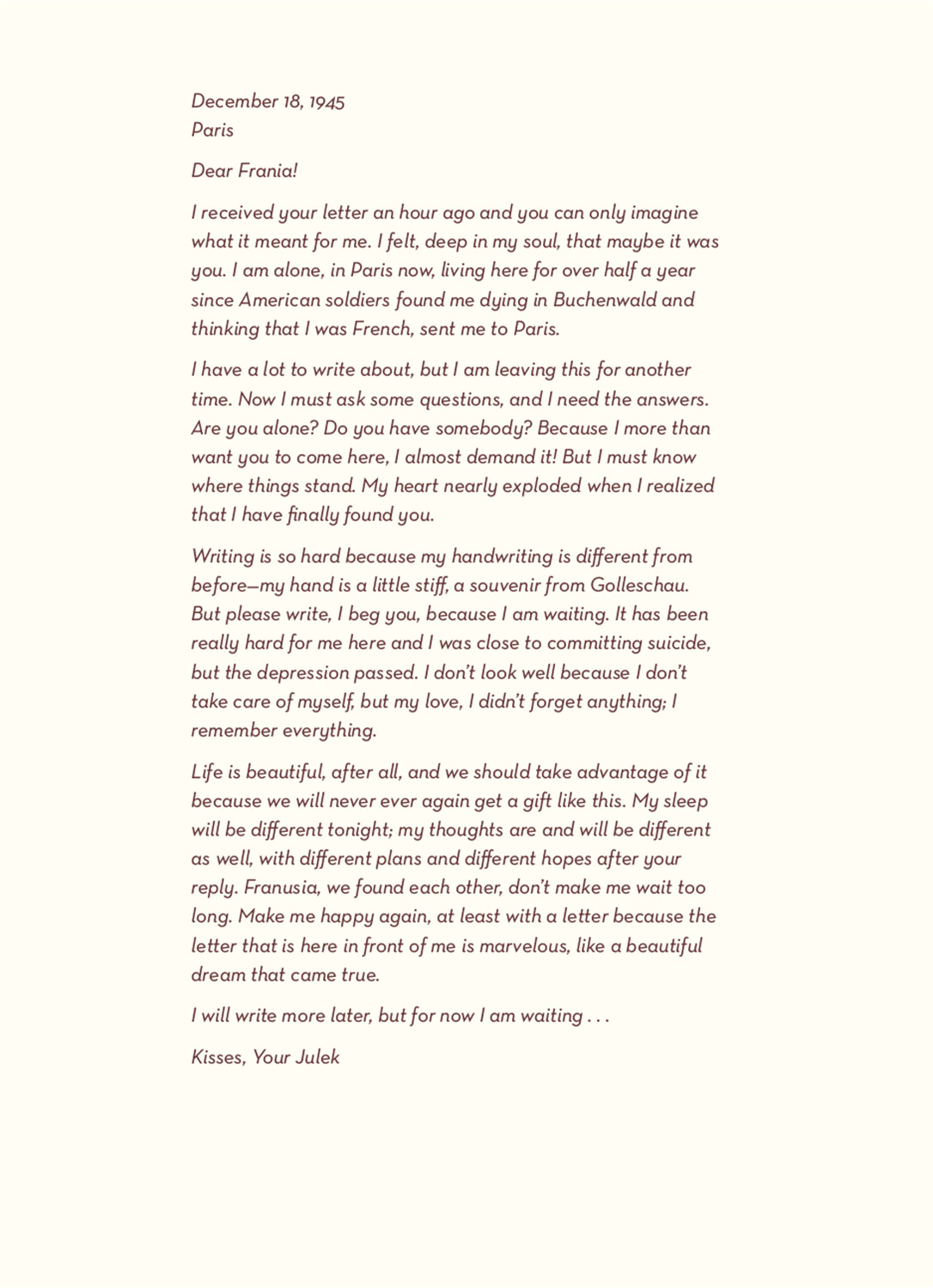

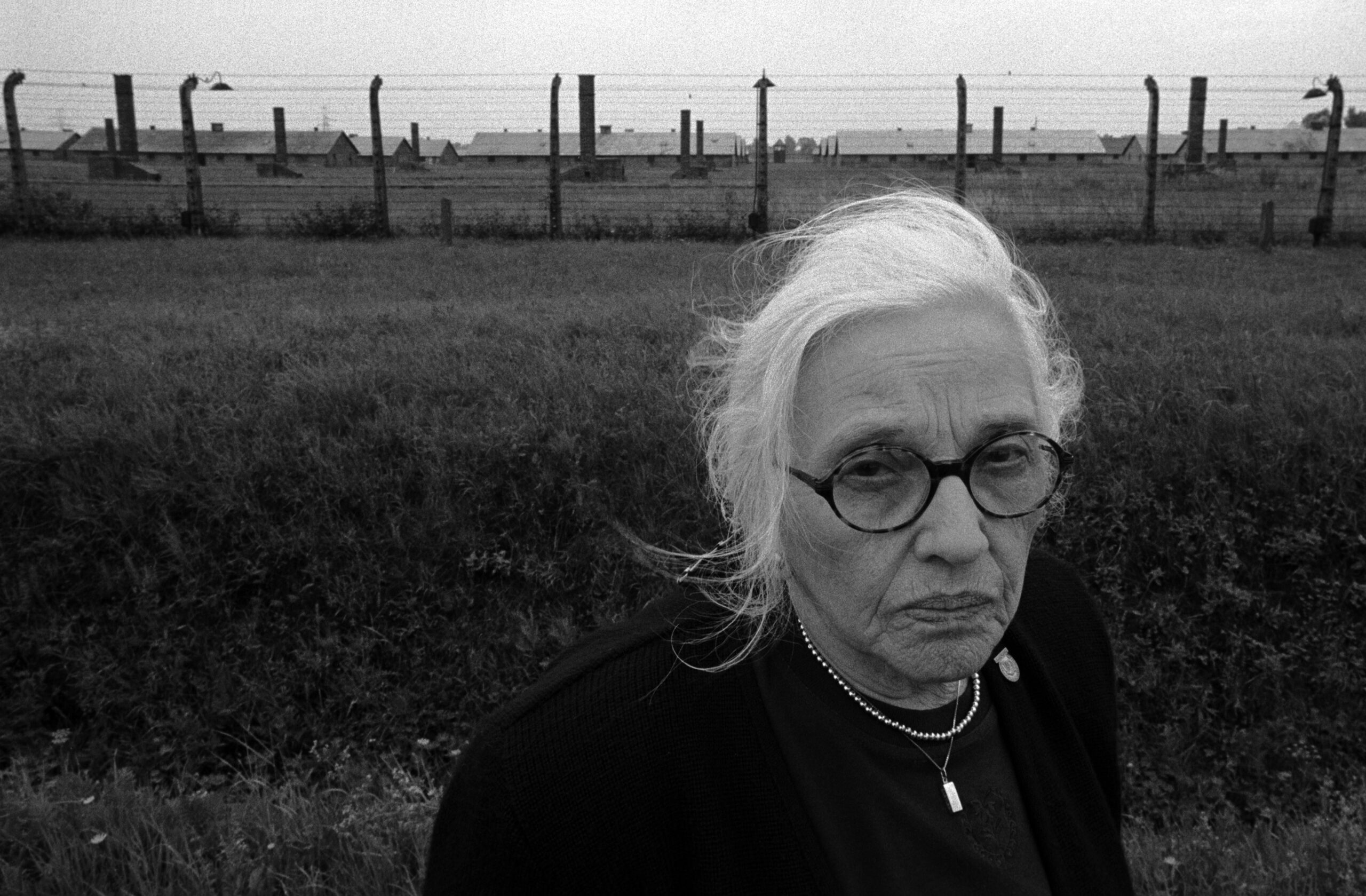

In fact, Sweet Noise is many books. There are letters, heartfelt and poignant love letters between his mother and father while they were separated and trying to navigate postwar immigration. There is his own memoir, clearly and elegantly told, about coming to understand his parents’ story. There are stories of his childhood and there is the journey he goes on with his mother, after his father died, a search for some closure and understanding, back to Europe. Hirshfeld is a clear and gifted writer as well as photographer and reading the story is as compelling as any image.

And there are the images, their own narrative, every one of them powerful, sometimes illustrating the text but more often than not offering their own story in parallel.

The narrative, the memoir, begins with what becomes a metaphor. “Ten years after my mother died I was in Brussels on assignment. I hoped to trace my father’s January 1946 route, walking from the Luxembourg train station to Madame Wilkomir’s apartment, photographing along the way as life streamed by. Yet Brussels had changed… I photographed around the entrance thinking I might slip into a place where I could channel my father’s spirit as he hurried up the steps on that winter day, his heart in his throat and his overcoat buttoned high to keep out the chill. What powerful, magnetic thoughts had raced through his head as he rode the train from Paris?”

He meets an old woman in a café, roughly his mother’s age, and discovers she too is a survivor. He continues, “…she told me she was Ellen Soyka. A jolt of recognition startled me, but the details remained just out of reach. How did I know that name? Walking toward the tram, I scoured my brain for the connection. Soyka, of course! Abraham and Zossia Soyka has raised my mother! I ran sweating back to the café, bursting with emotion. But she was gone.”

Sweet Noise is an act of recovery, simultaneously beautiful in its expression and horrifying in what it explains.

The first third of the book is simply the letters that Hirshfeld’s parents sent to each other. They discover each other’s whereabouts, reveal their love and longing and hope and desperation sometimes daily, give each other strength, share news and plans, and reading them I often felt as if I were inside something so intimate and true I was a voyeur without permission. But, of course, I kept reading. I was falling in love with their love.

As Hirshfeld writes, “My parents had met in a Polish ghetto in 1943, embracing a secret romance as the clock raced toward the time they’d be selected for Auschwitz. They both survived: my mother by escaping from a death march and my father with the liberation at Buchenwald. Eight months later my mother placed an ad in a small newspaper, inquiring if anyone had information about Julek Herszfeld. They reunited, opening the door to a love story with a future that promised to end their endless ordeal. Yet after less than a year, the turmoil of postwar immigration put another wedge between them and forced them to endure a second, lengthier separation, one that demanded a more complicated kind of resolve.”

The second two-thirds of the book are Hirshfeld’s memoir and his trip with his mother. There are memories of the camps, detailed and gruesome and difficult to read. And I will not quote them here because they deserve to be read in Hirshfeld’s telling. However, every story is another step on Hirshfeld’s path to a deeper and more personal understanding. Every story is necessary.

“Was Poland so vivid to me,” he asks, “because my spirt had been there before or because I saw a moment of poetry come to life as my mother stumbled back through time? Watching her step carefully over the exposed roots and the rubble of the cemetery, I had the eerie sense that she had slipped into the past through a portal reserved for survivors. Her need for closure fed my need for knowledge, as if shutting some doors might serve to open others.”

Because the letters and the revisit are so compelling, it would be easy to dimmish the power of the images in this book. Of course they are emotional and evocative and complex. They match the story, right?

However, as the book’s website states, “Max Hirshfeld is recognized as a master at spotting decisive moments while revealing the warmth and humanity of his subjects. He was born in North Carolina in 1951 and grew up in Decatur, Alabama. After moving to Washington, DC, he studied photography at George Washington University, graduating in 1973. His work has been shown at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Kreeger Museum, and is represented by leading galleries in Washington and Boston. He has won silver and bronze awards from the Prix de la Photographie Paris and been featured in Communication Arts, Eyemazing, and American Photography. Hirshfeld’s editorial work has been published in The New York Times Magazine, Time, Vanity Fair, and other national publications, and his advertising work has been showcased in campaigns for Amtrak, Canon and IBM, among others.”

If I did not know who was in the images from the stories, I would say the images were impressive. When I do know who I am seeing, and why I am seeing them, I would say the images catch up my breath and I am glad the door is closed.

Sweet Noise begins with an Introduction by Michael Berenbaum who, among many other things, played a leading role in the establishment of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and was its Project Director from 1988 until 1993. He writes, “Before it is too late, the faithful son seeks to understand the experience of his parents and thus the mystery of his origins. Max is a photographer, so the words of his journey must be read alongside his photographs. He is honest with the reader and with himself, knowing that sometimes he shielded himself form the immediacy of the moment by hiding behind the camera. Only in the darkroom would he have to confront what he had seen, in a place where lighting is limited and the process takes time. There, one can stop to grapple with an image before one sees the next. Not so in life. Not so on this pilgrimage.”

And Sweet Noise ends with an epilogue by Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat who writes, “This return ‘home’ was not only cathartic for his mother but opened his eyes to their history. He wished, as do so many children of survivors, that he ‘had been more receptive to all those stories she and my father had tried to tell me’ as he was growing up, so that he ‘might have been able to weave a richer tapestry of what life had been like in the heart of Jewish Poland.’ Ultimately, through the story of his mother’s return and his photographs, Max Hirshfeld in Sweet Noise has given us a glimpse of just hat prewar Jewish life.”

In an email, Hirshfeld writes, “The book is a deep dive and only reveals itself when it is in hand. I was really hoping that it would feel like a prayer book or similar without overwhelming the material or overshadowing the photography. David did a stellar job with his sensitive design.”

Sweet Noise, a profound synthesis of letters, memoir, images and analysis, is one of those very rare books that speak directly to the sense of needing to understand our place in a universe that is both incomprehensibly violent and capable of such tremendous love.

More information can be found at www.sweetnoisebook.com.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.