I often wonder why we are attracted to biography, and especially autobiography. My life is nothing like Benjamin Franklin’s, or Maxine Hong Kingston’s, or Anne Frank’s, or Mark Twain’s. Beyond a certain type of voyeuristic curiosity about what’s in other people’s historical cabinets, why do we find the stories about someone else’s journey so compelling?

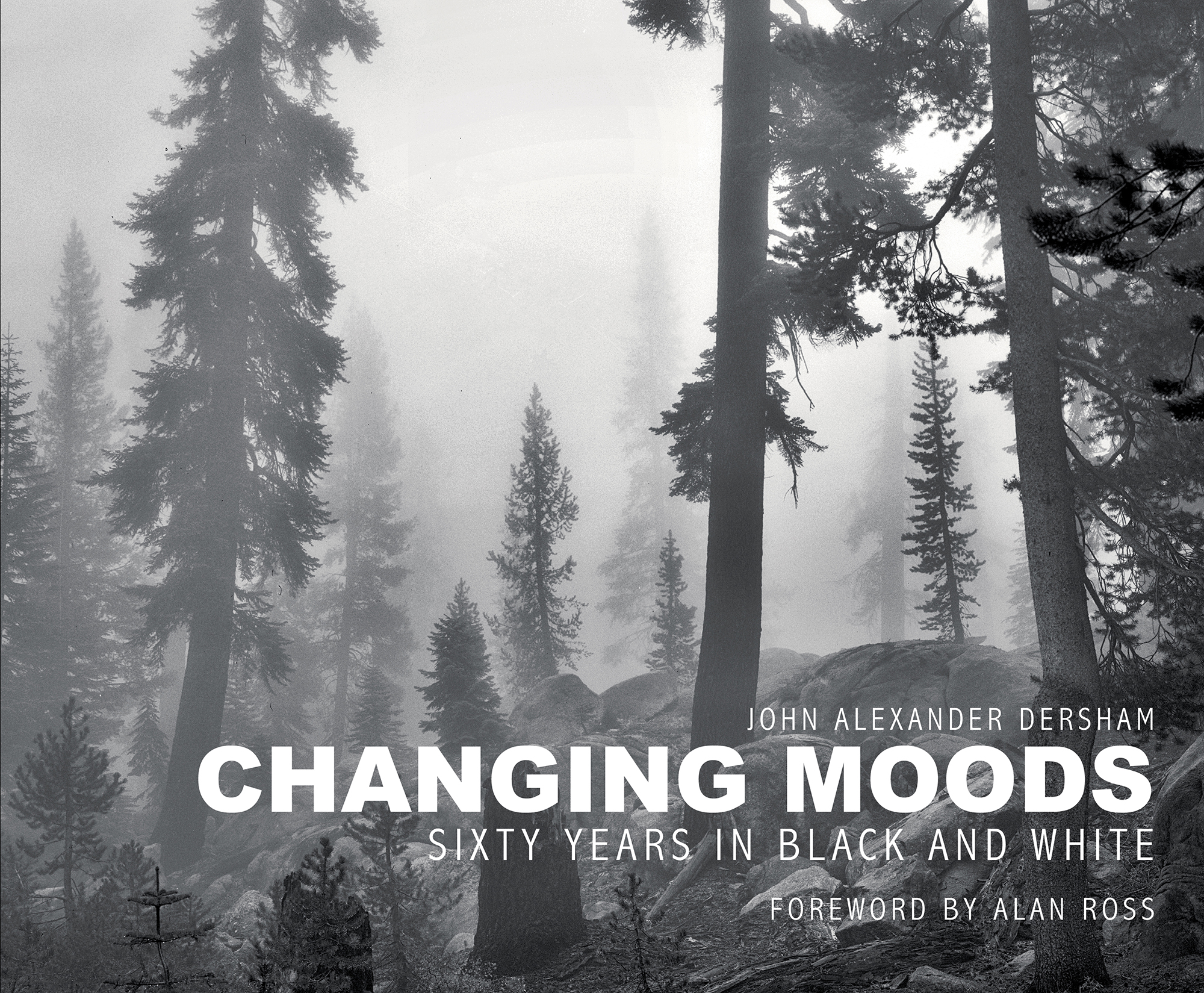

“Changing Moods: Sixty Years in Black and White” by John Alexander Dersham

Published by NewSouth Books 2021

review by W. Scott Olsen

Yes, there is the level of advice. Do this. Don’t do that. And there is the wisdom that comes from experience. We can get a head start on that by listening to what other people have learned.

But I suspect there is something more.

Biography and Autobiography are not the same as memoir. Memoir is the story of some trip, some event, something fairly well defined or limited. Biography and autobiography, on the other hand, are pretty much birth until the toner is gone.

What would compel someone, anyone, to write an autobiography? Vanity is hardly the answer. The obligations of fame or infamy or even complete ordinariness do not require a pen. But remember Sartre and “Hell is other people”? He did not mean other people are nasty. He meant we judge ourselves by how other people judge us, with whatever limited and imperfect information they have.

So, we understand the work of the autobiographer is to explain, to illuminate their legacies, to nuance his or her own stories in order to add a bit of grace.

But this leaves the question I started with. Why do we read biographies? Do I really care what someone else was like in third grade?

Yes, of course. Emphatically yes.

Context is (almost) everything. When I read the stories of other people, I invariably compare those stories to my own. It really doesn’t matter if the other person is Marco Polo or Martha Graham or anyone else. I read to learn the details. Sometimes those details simply make that person’s life more finely drawn (and thus my own a little less hellish, according to Sartre). Sometimes those details help me understand a world much larger than my own experience of it.

This can be particularly true for photographers.

Changing Moods: Sixty Years in Black and White, the wonderful new book by John Alexander Dersham, is an autobiography with several threads. Dersham is a remarkable and insightful black and white landscape photographer. He also had a long career in the film developing industry, then another career as a photographer for the tourism industry. The book is the story of his life, including marriage, kids, mortgages, the works. It’s also the story of the film developing world. Finally, the book is the arc of his life as photographer, from the very first image he took until the book went to press. All three stories braid together to make a deeply rewarding experience.

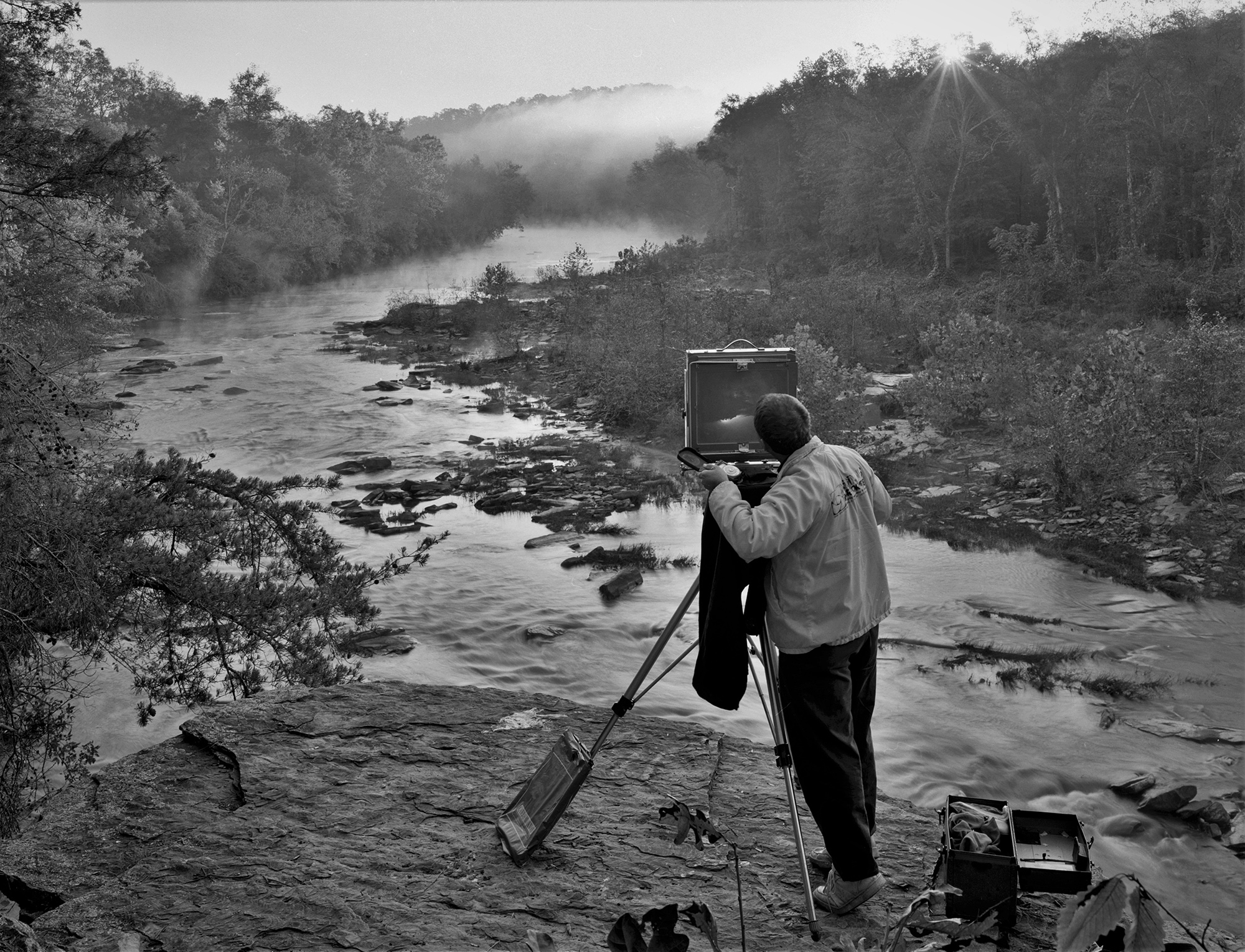

Derhsam is primarily a large format photographer. In the Foreword to the book, Alan Ross (Ansel Adam’s longtime assistant and still the exclusive printer of the Yosemite Special Edition negatives), writes: “…John Dersham uses the language of photography to reveal his passion for black-and-white large-format imagery and the visual feast of everyday life. He tells us a love story. This love is evident in his images that evoke the peace to be found on quiet country roads and friends gathered together, or in trees and towns, roads and rivers, an old general store next to a quiet leaf on a wet river rock… Dersham’s choice of camera also speaks volumes about his dedication to craft and mastery.”

Dersham’s life seems almost fated to photography. “When I was very young,” he writes, “Dad was director of health education for the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, which issued him a 4×5 Speed Graphic camera to take pictures of unhealthy local conditions in the late 1940s and 1950s. He learned photography quite well because the Speed Graphic required an excellent understanding of aperture, shutter speed, depth of field, and how to handle and load sheet film. Probably because of his interest, I got my first photographic developing kit the Christmas of 1964.”

Dersham and his father also had a small business that supplied topical fish to local stores, and one of their clients was an award-winning photographer who also owned a camera store.

Queue the theme music. The play has begun.

Changing Moods is a personal book. We learn the stories of Dersham’s parents’ courtship and marriage, his father’s occupations, his own attempt as a musician in Nashville, how he met his wife, and a great deal more. But the book is not random; it keeps coming back to his development as a photographer.

“I took my first picture on November 1, 1960, one day after my nineth birthday (on Halloween). In 1930, Eastman Kodak celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. The company had an anniversary promotion to inspire young people to begin taking pictures. Via a coupon from some magazine or newspaper, all kids turning twelve years of age in 1930 could receive a free Kodak Brownie loaded with black-and-white film. Dad was one of those five thousand-plus twelve-year-olds who got the now collectors’ item 1930 Brownie with a Kodak fiftieth anniversary seal on its side… I asked Dad if I could take some pictures with his camera on my trip the family was taking to Cape Girardeau the next day. He said yes….”

Changing Moods is divided into sections, one for each decade from the 1960s until the 2010s. Each section tells his personal story, his professional story (both as photographer and as an executive for Kodak), and includes images he took during that time. The result is I became as interested in Dersham as a character as I would in any text-only book. The details of job promotion, house-buying, etc., are unusual in a photo-book but here they serve to create an unexpected depth.

There are other elements, too. Several times throughout the book there are asides or mini-essays. For example, there are “Why Large Format?” and “Why Sunrise Instead of Sunset?” and “Image Impact.” Each of these essays delve briefly into some tangent that is likely a question already developing in the reader’s mind.

Reading Changing Moods, I became invested in Derham’s personal story. I was interested in the parallel story of the downsizing of Kodak as the digital age comes to the stage. And I was intrigued by the story of his move into the tourism industry. However, the real power of the book rests with the images.

Despite all the fine text, Changing Moods is a photobook. It is a photo autobiography, from start to now. The large format, black-and-white, mostly landscape images are often mesmerizing. Yes, there is the resolution and detail that large-format brings. But his sense of content and composition is sharp and moving. Black-and-white is a different way of seeing the world – everything from what time of day to shoot, to the interactions of line and light, to mood – and Dersham is a master. One nice part of this book is that the captions give technical details: date, place, camera, lens, settings, developer. Each little detail makes the work, and my understanding of it, more exact.

Despite the fact that the photo sections are large and deep – there are lots of photos! – I will admit that on my first read I skimmed past some of the images so that I could continue reading the story. I knew it would be easy to come back to the images. And the images I saw in the 1980s chapter, for example, would only become richer if I knew what happened in the 1990s and beyond.

When I went back, I found myself really examining and enjoying the photos. Part of the reason is that we share some geographic history in central Missouri (although he is just enough older than I am for us to have ever met). But the main reason is that his voice in these images is always one of invitation more than critique. Here, he says, is a story.

To be clear—most of us these days are not a large format or film photographers. The details of these stories have nothing to do with instruction or help. But there is something ethereal about the mind of an artist that is all bound up in time and place and culture and history and the ways technique is learned and held dear. Oftentimes, hearing someone else’s story let’s us know we’re not alone even if we’re not really doing the same thing.

Why do we write or (in this remarkable instance) image autobiography? To offer the world a more precise view of what we value.

What do we read, or view, an autobiography? To enjoy and to learn.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.

John Dersham

December 9, 2021 at 21:26

Thanks so much for this great review. I am extremely honored by it.