There are lessons everywhere.

Not all of them are direct.

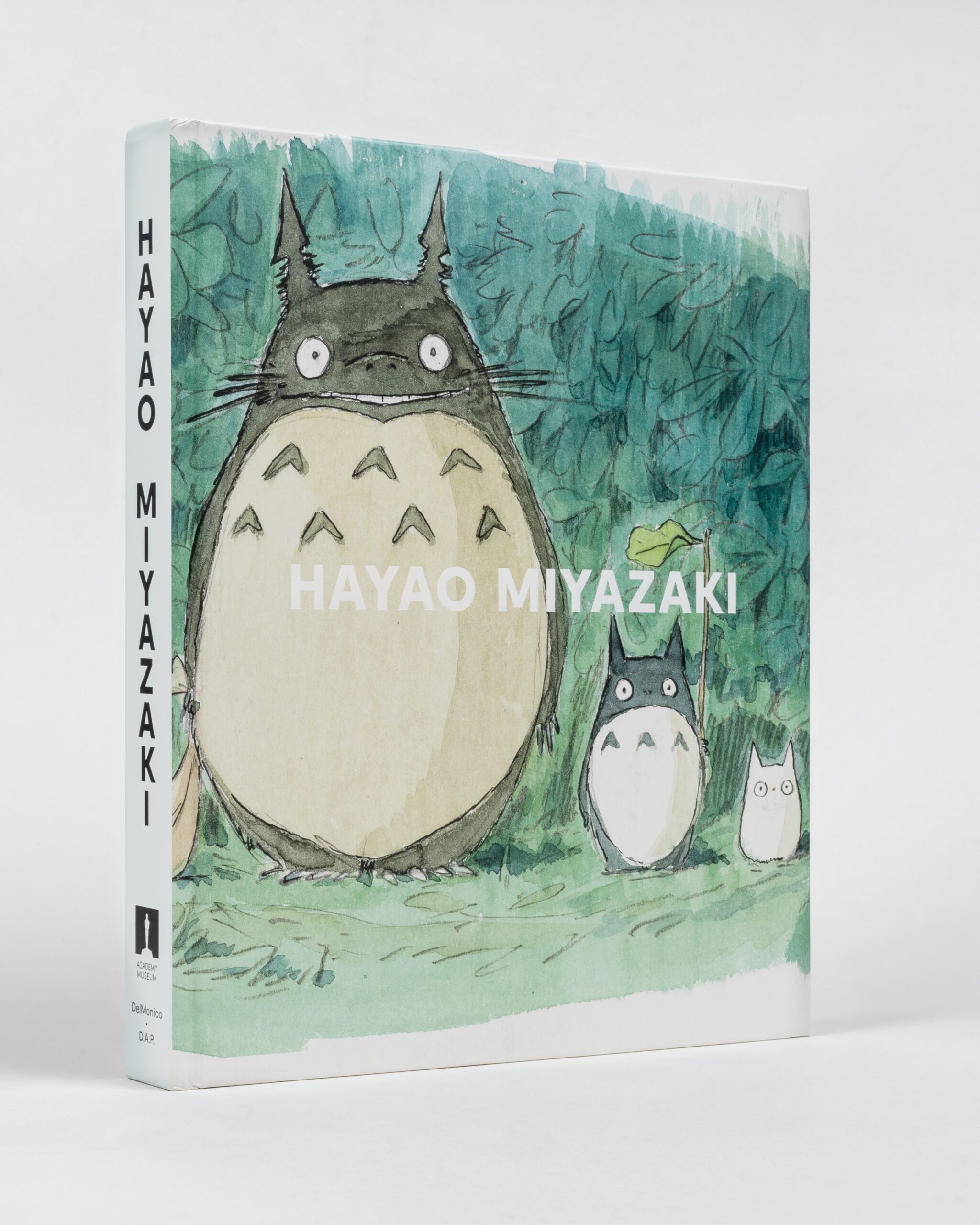

“Hayao Miyazaki” by Jessica Niebel

Published by Delmonico Books, 2021

review by W. Scott Olsen

Especially for photographers, there is a world of emotional challenge and inspiration that has little to do with a still image. Listening to Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, for example, provides an emotional touchstone we recognize when we’re next in the field.

Yes, we think, framing a river from some new vantage point. I know this feeling. This is true.

Watching a play in a theater, even though we may not be thinking about blocking—the way actors move about the stage—we are aware of how the stage framing effects meaning. There is both tension and potential in the way the stage confines the action and we use that feeling when we consider our own composition and framing.

Our sense of irony is developed in conversation. Our sense of beauty may come from a poem.

In other words, photographers take in everything. What we give back is expressed in the still image.

Of course, some influences are fairly close. Filmmakers and photographers are not siblings, but they are certainly first cousins. We share concerns about light and shadow, about composition and focus and exposure and detail and, and, and.

We all have a faith that the visual image can influence the soul.

This is not a limited connection. Along with the advent of CGI in film we have tremendous developments in still image post processing. Animation in motion pictures has grown to explore profound as well as subtle moods and expressions.

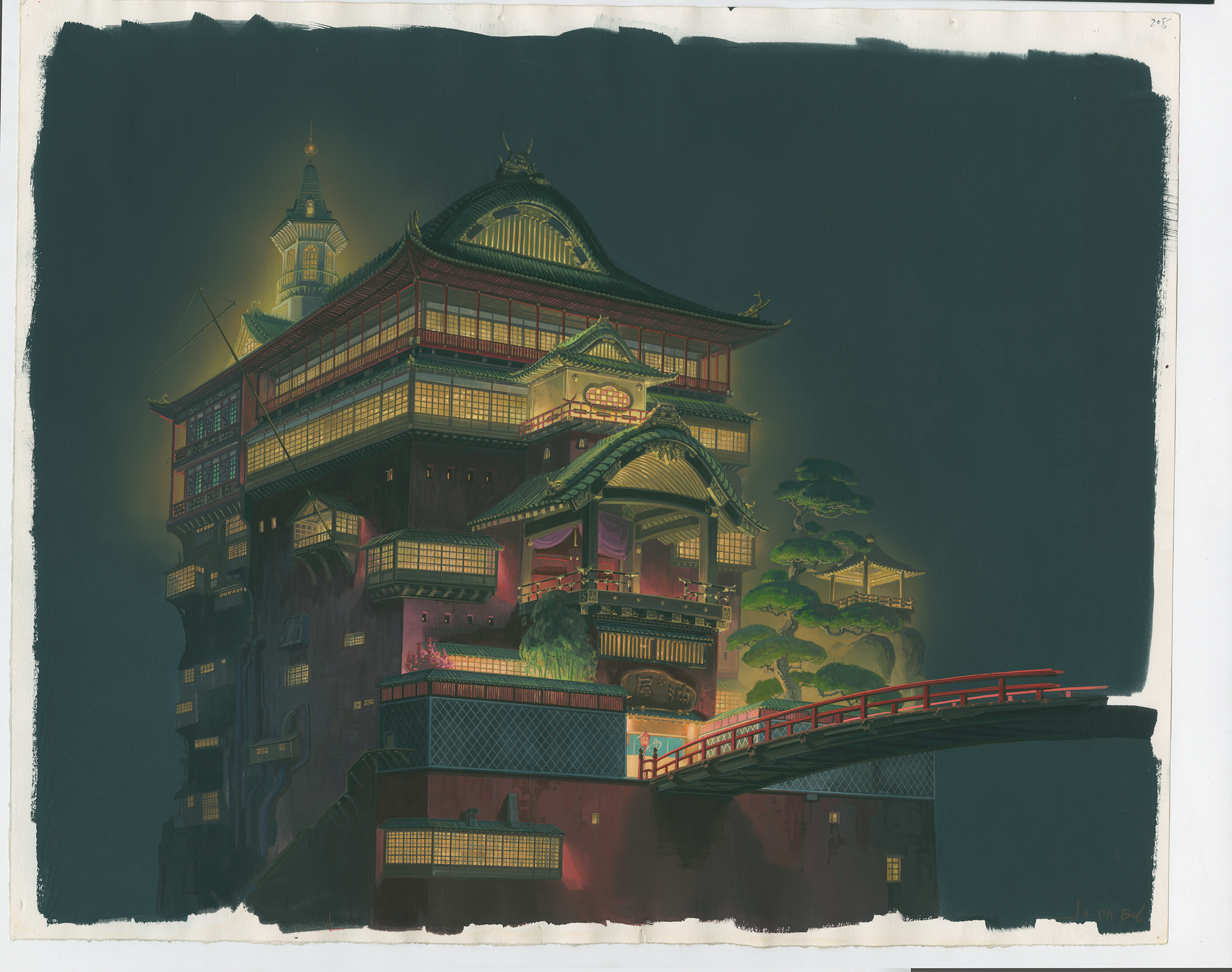

I am thinking about all this because of a new book on my desk. It is not a photobook. Simply titled Hayao Miyazaki, the book is artistic biography, aesthetic treatise, creative process explication, and celebration of the filmmaker’s work. Miyazaki, of course, is the artist who made films like Kiki’s Delivery Service, Spirited Away, and most recently Earwig and the Witch.

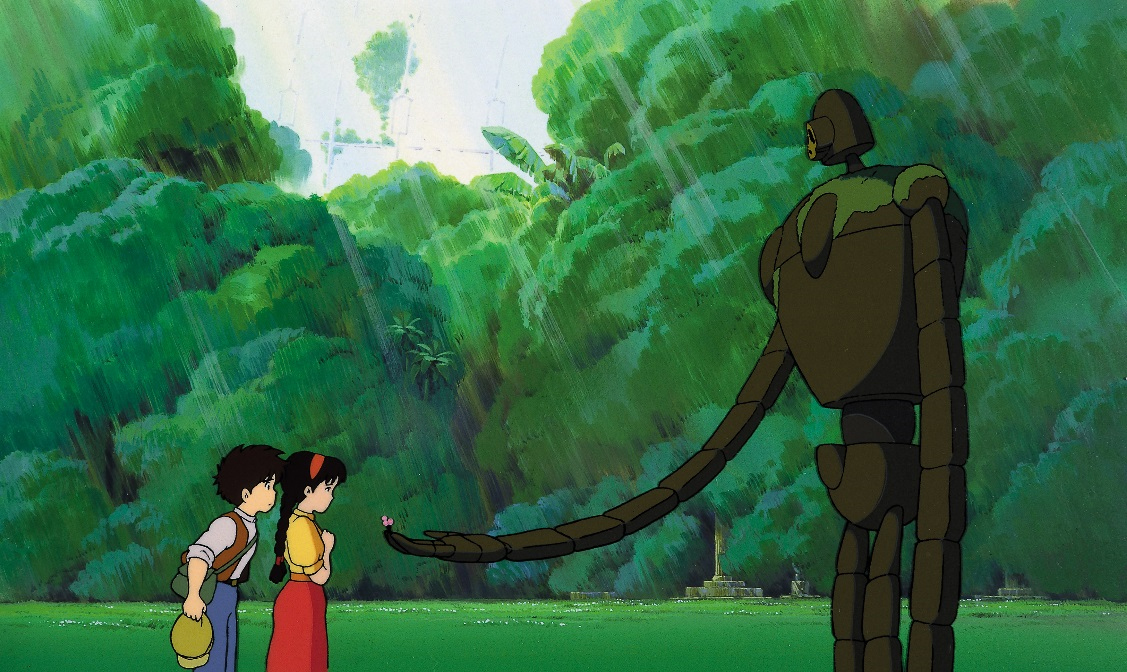

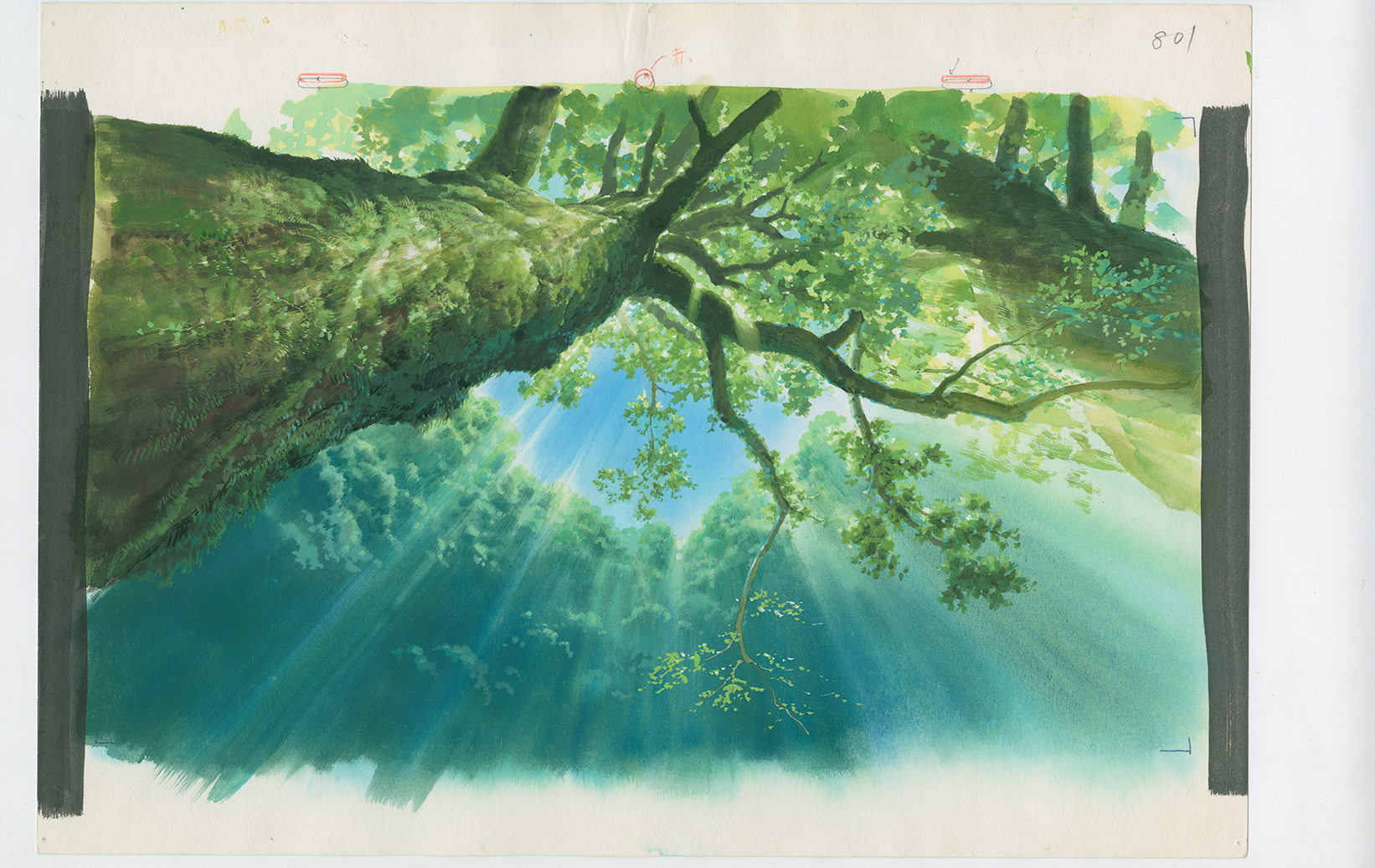

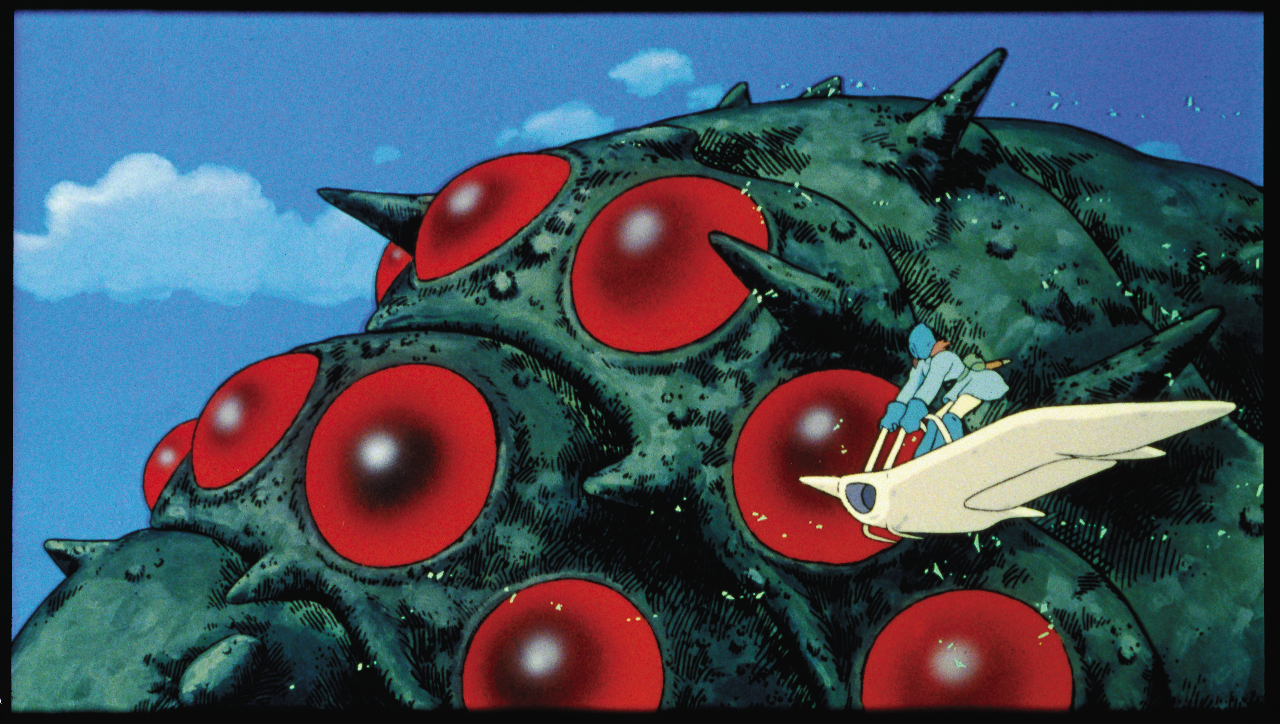

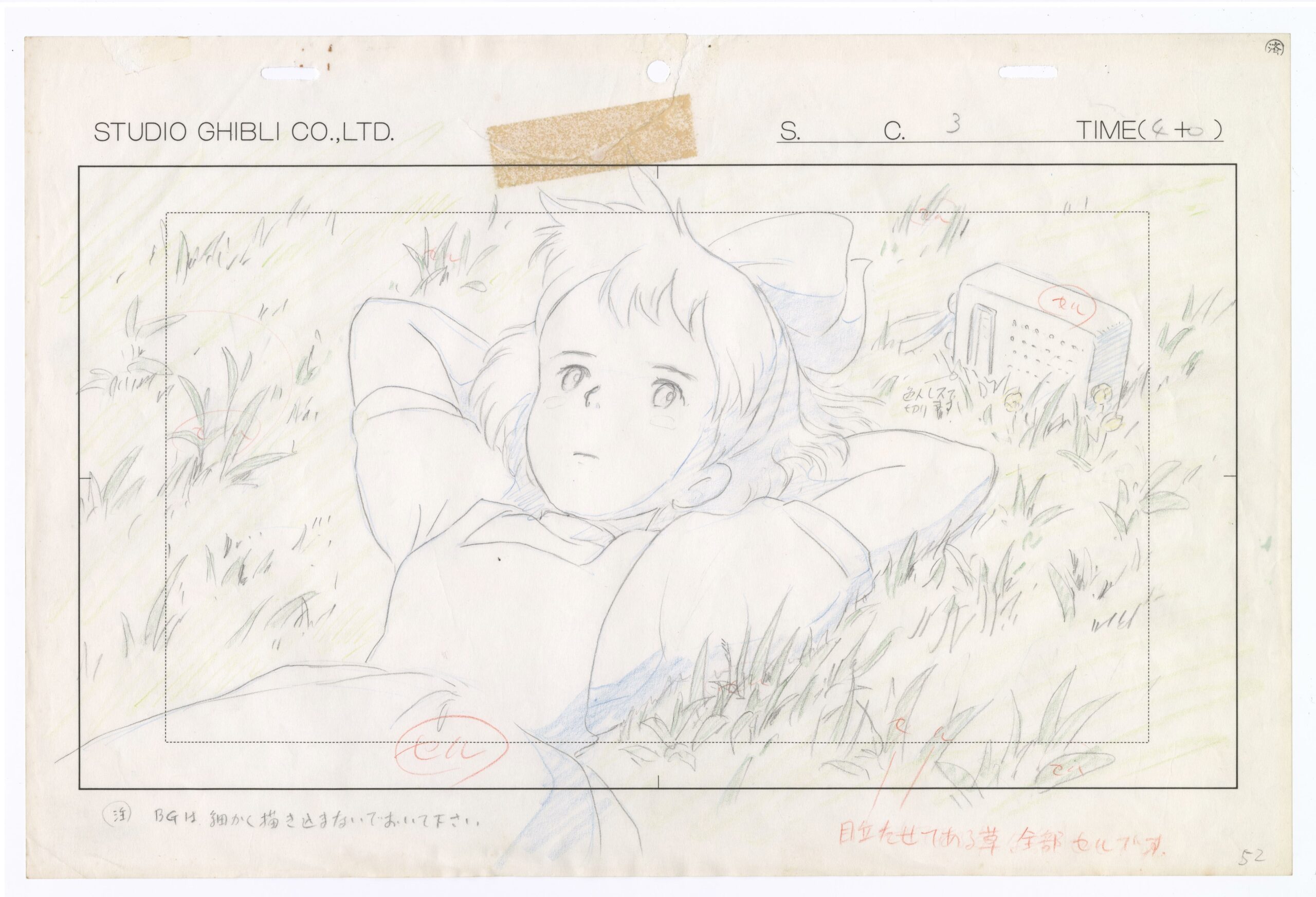

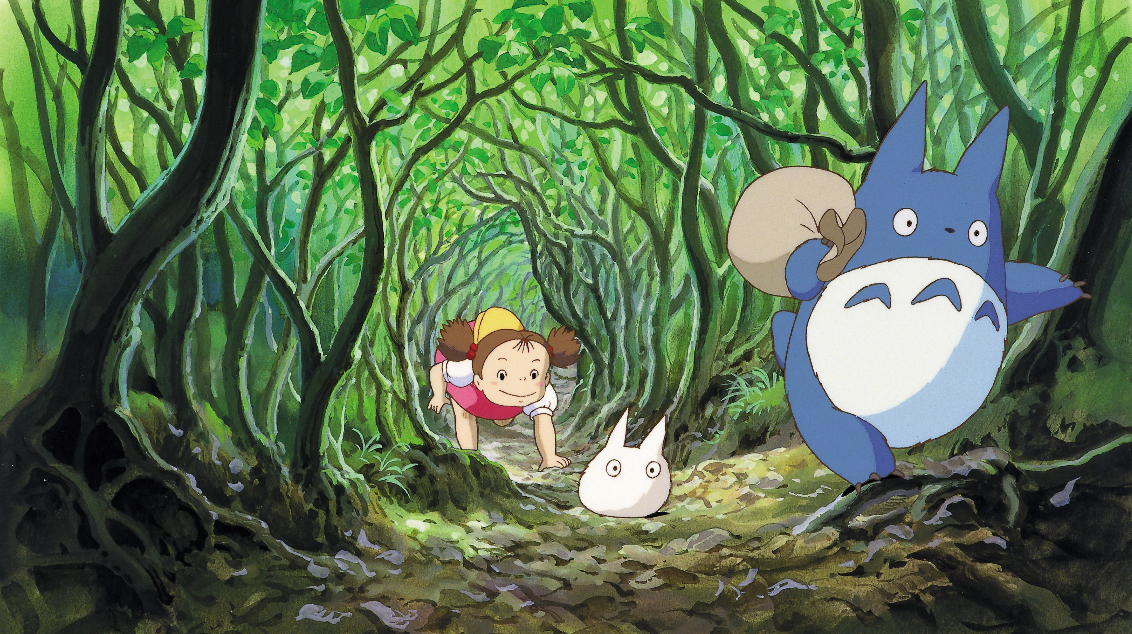

According to the book’s press materials, “This book is published on the occasion of the inaugural exhibition at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, opening September 30, 2021, and is produced in collaboration with Studio Ghibli in Tokyo. It accompanies the first ever retrospective dedicated to the legendary filmmaker in North America and introduces hundreds of original production materials, including artworks never before seen outside of Studio Ghibli’s archives. Storyboards, character designs, layouts, backgrounds and production cels from his early career through all 11 of his feature films, including My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), offer insight into Miyazaki’s creative process and masterful animation techniques.”

The book is breathtaking. Jessica Niebel, exhibitions curator at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has created a tour de force. She writes, “Perhaps the films feel so strangely familiar because they share their creator’s understanding of the world, of humanity, and of the times we live in. Miyazaki is much more than an animator or a director of films. He an auteur and a philosopher who seeks to express his insights, values, and vision through animated films.”

This is not a book that needs to be read from front to back. It allows dipping in as well as deep dives into any chapter.

In one of two brief prefaces, Toshio Suzuki, Producer at Studio Ghibli, writes, “When Miya-san comes across a building or landscape that he likes, he gazes at it for a while, taking it in. It may be for five minutes or ten minutes, or even several hours. Take Lady Eboshi’s mansion in Princess Mononoke. I was astounded when I took a look at the building Miya-san had drawn. Some two or three years earlier, he and I had traveled to Otaru, in Hokkaido, to see what is called a “herring mansion,” built by a fishing magnate who had earned his fortune from the herring industry. That lavish building had been transformed into Lady Eboshi’s mansion. When I pointed that out, Miya-san said to me, mischievously and full of delight, “This one’s three times the height.”

There is a lesson about patience here. There is a lesson about looking at a scene without a camera, imagining how that scene might be best rendered, about thinking through what we’re doing. Especially for those of us who work in photojournalism, street photography or travel work, patience is such a luxury we often fail to even think about it.

Remember William Wordsworth’s famous line—“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Just change “Poetry” into “Photography” or, in this case, “Miyazaki’s work.”

There are insights all through this book. Anyone interested in anime or manga or animation in general will find this book richly detailed and compelling. Anyone interested in contemporary aesthetics will recognize and appreciate the careful going through of each film in philosophical as well as process terms.

Which brings me back to photography. While there are a handful of photographs of Miyazaki and others at work, they are incidental to this volume at best. What I find wonderful are all the stills from the films, all the sketches and drafts and composition studies. This book is very much a book about process, though not in a technical sense. This is a book about how to bring ideas and emotions into visual form.

Every chapter of this book holds insight for photographers. For example, the epigraph to the chapter “Creating Worlds” reads, “The creation of a single world comes from a huge number of fragments and chaos.” The creation of a single frame to a still imaging coming from a huge number of fragments is not a new idea. But add in that bit about chaos. Most photographers would think chaos is something to be avoided or controlled. But to celebrate chaos as part of the composition? It’s not a new idea, but I had never thought of it in those terms.

That same chapter then begins, “Miyazaki’s worlds are created not just for the eyes but for all the senses. His sceneries are immersive and experiential, realized through a passion for detail paired with an observational perceptiveness that ‘allows us to experience the meaning of a landscape or the climate on a much deeper level.’”

Likewise, the chapter called “The Process: Worlds” begins, “What rushes forth from inside you is the world you have already drawn inside yourself, the many landscapes you have stored up, the thoughts and feelings that seek expressions…” followed by “The foremost challenge for background artists is capturing the intensity and complexity of Miyazaki’s ideas in their paintings: ‘Each shot should express the film’s world in its entirety.’”

Paging through this book is a profound joy. The text reveals a spirit every photographer will recognize as kindred. Every image will be a cause for slowing down and considering not only the real beauty, but the adroit skill. The early sketches are as interesting as the final production images.

Any photographer working in still lifes, in abstract or conceptual work, will need this book. Every photographer, no matter what genre, will enjoy it.

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.