Every now and then, a photobook comes along which is extraordinary in every possible way. Not only are the images bold as well as nuanced, the whole conception of the purpose of the book – from content selection to book design to the incorporation of explanatory text – is so well done it sets a benchmark for others to follow. Holding it in your lap or hands, you feel a part of something wonderful, necessary and smart.

The new book, Chris Killip, a retrospective of the artist’s career and influence, is this type of wonderful book.

“Chris Killip” by Ken Grant and Tracy Marchall-Grant

Published by Thames & Hudson, 2022

review by W. Scott Olsen

In the Forward to the book, Brett Rogers, Director of The Photographer’s Gallery in London, writes,

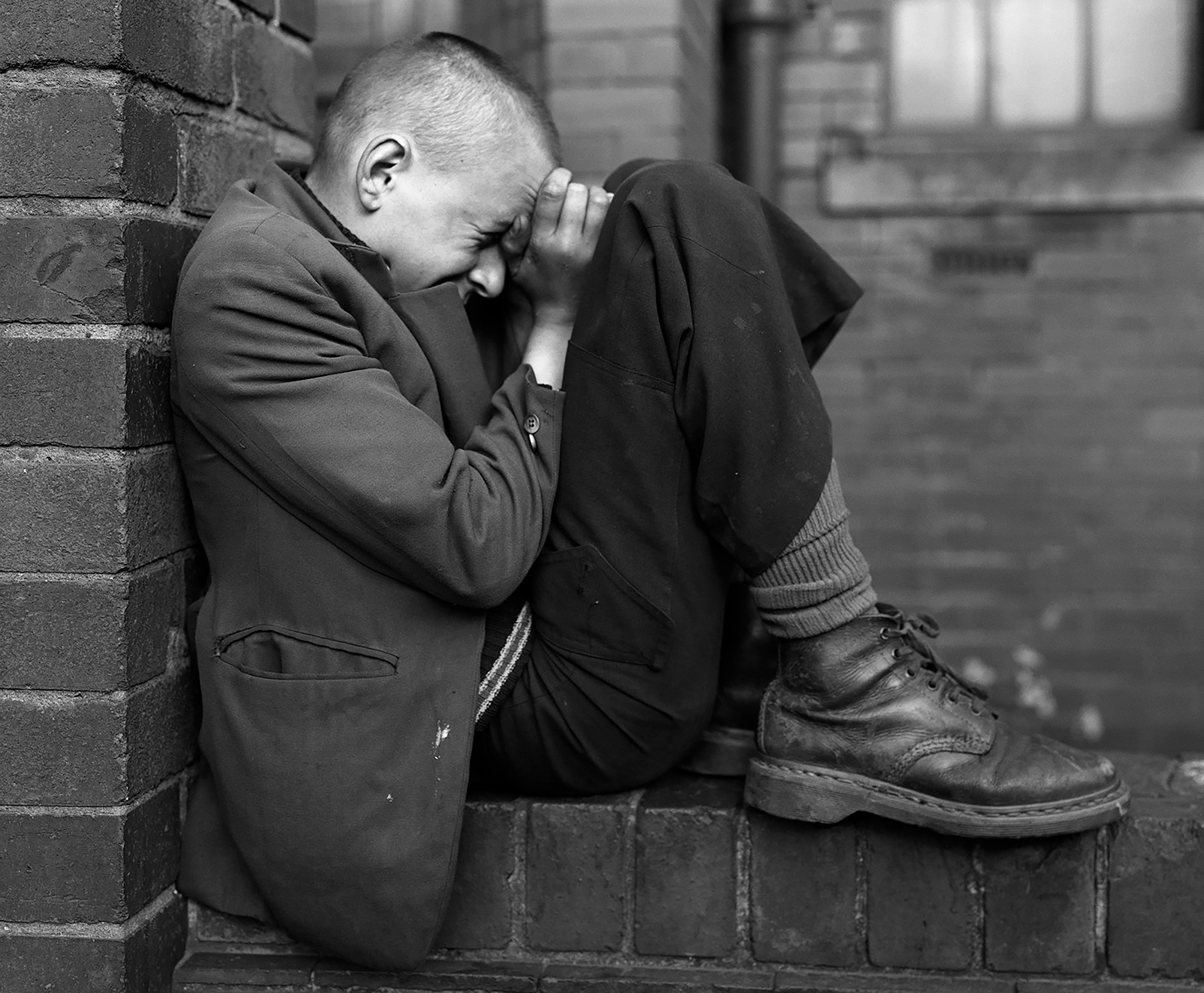

This important publication offers a comprehensive retrospective – and long overdue reappraisal – of the British photographer Chris Killip’s remarkable life and career. It is a striking reminder of how his images reshaped and challenged our understanding of communities through the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond.

The force of Killip’s vision, informed by his commitment to tell the stories of ‘those who had history done to them – who have felt its malicious disregard,’ maintains a contemporary resonance beyond the realities of the people he worked to portray.

As a retrospective, the content and design of this book are genius. There are more than 350 images. There are four chapters, each covering a portion of Killip’s history. Within each chapter, there are subdivisions that identify locale. This division and then subdivision focus and direct attention to something deeper. Also, within each chapter, there are deeply researched and well-told narrative essays that explain the chapter’s historical context and geographic setting.

For example, in the essay titled “A Letter Home,” which fronts chapter one, photographer and critic Ken Grant begins,

Beyond the black fingers of Langness, heavy gray knuckles of stone still push through the grasses of the southern tip of the Isle of Man. Some of that land has now eroded to nearly nothing. Where it meets the spit and spray of the Irish Sea, and the place Manx once called Oaie Ny Baatyn Marroo, the Graveyard of Lost Ships, there are gaps in time and geology that might cast doubt that an era existed at all. Yet its name, Langness, kept now as it was in Norse, quietly affirms that things did happen here, as clearly as languages speak to the contests a land has endured. Trouble came here, blown in on difficult seas.

When Chris Killip photographed Langness Rocks in 1971, he did so with a careful, deliberate approach that resisted the fluid tendencies of the time. He already knew that changes were reshaping the island.

Later in the book, photographer Gregory Halpern offer a personal reminiscence.

I come from a verbose family, and so it particularly struck me that Chris seemed to speak only when necessary. Once he invited a few of us for barbeque after a guest artist lecture, which he liked to do sometimes. In retrospect, I remember Chris rubbing his eye a bit during the meal. I later learned that during the meal he had lost vision in one eye—the beginning of a degenerative eye condition—but Chris didn’t mention it until a few days later. Everyone was having a great time. ‘Why ruin it?’, he said with his classic half-smile.

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

Memories and insights offered by curator Amanda Maddox and sociologist Lynsey Hanley are equally engaging. “As it turned out,” Maddox writes, “his humility belied a lyrical and delicate memory, complete with an acute ability to see the poetry that connects disparate, non-linear moments in time.” Hanley recalls, “A grounding in the work of Chris Killip and his contemporaries shows us not what was lost, but what was actively destroyed to make a world in which we couldn’t win. The only alternative is to make a new one. These photographs capture history in process: a preparation for revolution, in whatever form it takes.”

Killip was, and remains, an essential voice. However, as necessary as this book may be as retrospective and reappraisal, this book is also a powerful and moving introduction. The images, all of them, have that special, ineffable quality of photographic talent and voice.

Each of these images is honest, uncontrived, and piercingly insightful. While I am not about, in this review, to attempt an overview of Killip’s life or career, suffice it to say he never studied photography and was also the chair of the photography department at Harvard. His subject was never the affluence or the comfiness of the American Northeast. Instead, his subject was insistently the working-class British. All of the images in this book are black and white, many of them candid portraits which give light to a type of desperation that also contains a sense of integrity and nobility. Even the simplest of these images combines an emotional and political heart-punch.

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

Chris Killip is edited by Ken Grant and Tracy Marshall-Grant. Their selection of images, their ordering and relation to each other, is inspired. This book goes one step farther, though, in its design and layout. Most of the images are full page presentations, although many are smaller. The essays are punctuated by small images, too. What is remarkable is how well the images work together. Perhaps it’s only because each section revolves around a particular place, and places have their own sense of visual cohesion to the landscape and general mood, but reading through this book, the design as much as the content made me feel I was holding a more detailed, more organised collection that leads to understanding and insight.

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/ Magnum Photos

The real power of this book is twofold, combined. The images are evidence of genius. The text is that extra bit to make me understand and give a shape to what was going on. People who are familiar with Killip’s work will appreciate the detail. People who are unfamiliar with Killip’s work before holding this book will be grateful and amazed.

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

© Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.